To Tony Sparks, author of Tent City, Seattle: Refusing Homelessness and Making a Home, the self-governing tent encampment Tent City 3 is as iconic and integral to the city’s social fabric as the Space Needle. Made possible by a 2002 consent decree that allowed the group to live legally on privately held land for 90 days at a time—the first such move by any US city—the camp is a “regular feature of Seattle’s neighborhood landscape,” Sparks writes, due to its “persistent peripatetic existence.”

As a graduate student at the University of Washington in the mid-aughts, Sparks lived in Tent City 3 for seven months, contributing as other residents do to the encampment’s ongoing maintenance and negotiation with landowning religious groups, city officials, service providers, NIMBY neighbors, and others governing the place of Tent City 3 and its residents. Tent City, Seattle, which Sparks says he began writing in 2020 “entirely as a rage piece,” is the culmination of that work. It argues that self-governance lets encampment residents rebuke how housed people and homelessness services perceive them, opening up cracks in the colonially determined ways Seattle governs shelter and movement.

In an interview with The Stranger, Sparks shares how he gained Tent City 3 residents’ approval to conduct research there, contextualizes his academic approach, and describes potential policy changes that could change how Seattle addresses shelter and the right to call a place home.

I’d love to start off by hearing more about how you arrived at Tent City 3 as the site of your research, both in terms of the negotiation with camp residents to have that happen, as well as the intellectual and ethical questions that drove you to Tent City 3 specifically.

Tent City 3 as a research site was almost an accident. I found out about the tent city because they were just right down the street from me. I was living by Seattle University, and they had set up down there. So I literally walked by them every day, and I became sort of hi-bye friends with some of the people who lived there. When it came time to actually start research, the process was pretty simple. I called up [grassroots housing organization] SHARE/WHEEL and told them what I was thinking about doing, and they said, “Okay great, come to a camp meeting and pitch it.”

I went to a camp meeting and by that point they were no longer at Seattle University. They were at a terrible, awful, rat-infested, abandoned motel parking lot just north of the Tukwila border, and there were maybe 30 people at this camp meeting, and we were all huddled under this tent, and it was rain-snowing, and it was miserable. And so the discussion started, and what it came down to was, if I was willing to move in and share this miserable environment with them, then they’d be fine with it. I think they wanted to see if I would be willing to be there and participate with them. The next week, we had to move out of that place, and they wanted me to help them move before I moved in. People who were at the prior meeting knew me, but I introduced myself at the first meeting because a lot of people show up when you come to Capitol Hill. I did a Q&A and then just became known as the graduate student guy.

How quickly was your role or position within the camp de facto accepted? You mentioned a turnover of people coming and going, so I imagine the 30 people who voted yes to you being there were not the same group on Capitol Hill or later.

Two things worked to my advantage. First, weekly meetings, where I could say, “This is who I am, and this is what I’m doing.” Second, the thing about living in tents with 100 people is that the gossip is ongoing and relentless. So everybody knew, and everybody peppered me with questions. But that doesn’t mean I was universally accepted. There were definitely people who had no interest in talking to me or being anywhere near me, and I just sort of let that roll. If they stayed long enough to where I got to know them, then sometimes that changed.

You participated in the weekly requirements of the camp, but you were also in grad school. So I’m interested in what you were doing day-to-day while also living in Tent City 3.

It was a lot, and it really made me appreciate how it is to be unhoused on a daily basis and have a job. I was teaching, so I would get up, do my security shift [at the camp] early in the morning, jump on the bus, take my classes, teach my classes, then go back and do whatever other meetings or other volunteer stuff was on in the camp. After I had been there for a couple of months, when [school] went from winter to spring quarter, I invited everybody at the camp to come take my classes if they wanted to, so I always had three or four people from the tent city traveling around with me to my class. And that was great, they got to share their experience with students, and I hope they maybe learned something also.

But it was hectic because I had to look nice to teach. And you can only carry what you have with you to laundromats and gyms. Five dollars a shower, $5 a load—it’s expensive to just get up, go to work, do the things you need to do, and come back, especially If you don’t have a place where you can stash everything, or a place where you can do laundry, or a place where you can keep your food. So a lot of my time was spent doing social reproduction, keeping myself going. Luckily, I could take my clothes to my girlfriend’s house for laundry, so I did that a lot.

Speaking of this interplay between the academy and your interlocutors: A core thesis of your book is that residents of Tent City 3 rejected a lot of external perceptions in a way that rebukes settler-colonial tendencies or forces. I’m curious how much of that is sort of an intellectual lens versus something that was stated pretty explicitly by the people you knew who lived in Tent City 3.

No, it was stated extremely explicitly. As a matter of fact, that’s one of the big things I learned in this whole process. People’s motivations were expressly to counter the experiences of being identified as “homeless” or being forced into those subjectivities. It was absolutely explicit. I don’t think I put this in the book, but somebody told me, “The worst part of being homeless is not not having a place to live. It’s being treated like you’re a homeless person.” And that was universal.

There’s this point where you’re talking about Tent City 3’s community credits system, and a Tent City resident mentions churches, outreach, and charity. “Instead of poor African babies, it’s us,” was the quote from the encampment resident, speaking to Tent City 3’s receiving a very Christian form of charity. It seems like the most explicit mention in direct quotes of a colonial practice. I don’t know what you make of that.

I’m glad you picked up on that. In an earlier version of that chapter that got taken out, I had a whole little treatise relating the management of unhoused people to a famous theory, Rostow’s stages of growth, which you’ve probably heard of as social evolution—“primitive” societies are hunter-gatherers, and then once we become advanced and modern, we’re all good capitalists. People in the camp were making those sorts of connections between the spaces they were relegated to and assumptions of their backwardness or ignorance or inhumanity.

Maybe I’m reading this historical development incorrectly, but Tent City 3 established this precedent of self-governance, and then city government co-opted the self-governance model and expanded the number of sanctioned encampments that exist within Seattle that depart politically from Tent City 3. These other camps are often referral-only and talk about service provision, like you say, instead of governance. I wonder if you think that’s too pessimistic of a view—whether those sanctioned encampments exist so that unsanctioned ones can be swept.

That’s a complicated question. I think there is simultaneously room for hope and dread. The expansion of sanctioned encampments does provide fodder for cracking down on and illegalizing encampments that aren’t sanctioned. That said, I think that as long as the nugget of the idea of self-governance exists within those Seattle camps, there is room for experimentation, there’s room for expansion, and there’s room for conversations to happen. I’ve had the unfortunate opportunity of visiting encampments where there was no nod to self-governance and that were just essentially outdoor prisons for people who hadn’t committed any crimes.

When I set out to write this book, it started entirely as a rage piece. I started writing it in February of 2020. At the same time, I was doing outreach here in San Francisco talking with people who are being shoved into just horrible, horrible conditions. And then I came up to Seattle, for a funeral of all things, and saw the same thing there. But as I went back to my research interviews and documents, it became much more hopeful, seeing that, in any sort of condition, people will refuse and then reclaim their humanity. And it becomes possible for other people to recognize that humanity. It made me feel like it’s not a done deal. There is space.

But how much do you think that kind of optimism would still exist if you had conducted your research in 2024 rather than 2006?

Most of my interactions now are with people who are living in unsanctioned encampments just trying to get by. And, you know, there’s this case before the Supreme Court now, the Grants Pass case, whether or not it’s cruel and unusual punishment to take away all the conditions of living for another human. I don’t know if I were to do this exact research over again if it would be as positive. But I do feel like, by telling the stories of the cracks in what seems like a totalizing, punitive carceral system, that it leaves more space to find new ways of being. So, you know, at the end of the day, it’s not so much whether this research would be different, but can this research be part of a growing symphony of other people doing other things differently?

At the end of the book, you insert this caveat that you’re not trying to be prescriptive in your conclusions. But is there anything you see as a feasible policy shift or other intervention that could address the lack of shelter in Seattle?

From a policy perspective, opening ourselves up to understanding the various ways in which people can be at home, when, in homeless policy, there is no concept of home, and there’s no concept of being together. And so I think policies could be formulated that foreground the idea of home. What would it mean to have a right to belong somewhere and to someone? This is slightly different from Land Back or Right to Remain, because the right to be at home is something that extends beyond geography a little bit. It’s a different thing to say there should be a right for housing, which there absolutely should, and that there should be reparations and lands back, which there absolutely should. But there also is space to question our ideas of exclusion and hierarchy, foregrounding home as a right to membership or right to being in community that is spatial and social and political at the same time.

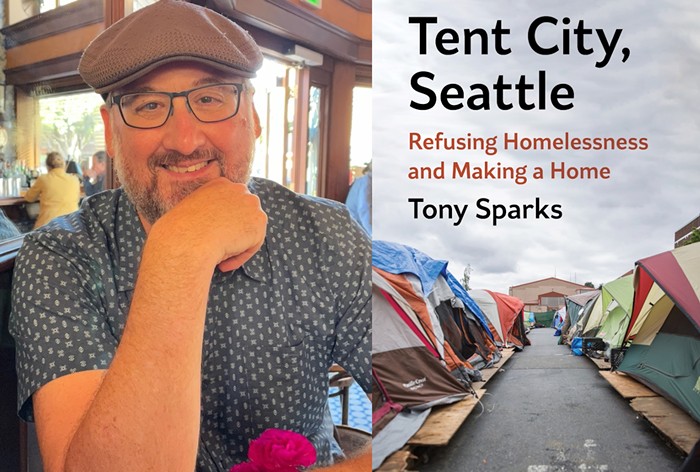

Tent City, Seattle: Refusing Homelessness and Making a Home by Tony Sparks is out now on University of Washington Press.

Adam Willems

Source link