Maybe it was a faded poster in your school cafeteria or a worksheet in health class, but if you attended school in the 1990s or 2000s, you’re almost certainly familiar with the food pyramid.

The graphic dominated U.S. dietary education until 2011, when the federal government replaced it with MyPlate, which emphasized fruits and veggies as making up roughly half of a healthy diet.

Today, health leaders and some influencers are still lashing out at the old pyramid, with its grain-heavy focus, blaming it for some Americans’ poor health. As Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced December plans to unveil new federal dietary guidelines, we looked back at the old food pyramid. Was it really that bad? And did it actually change how we eat?

And what do experts (who aren’t trying to sell you something) say is a “healthy, balanced diet,” anyway?

Old, but not as old as the pyramids in Egypt

The iconic food pyramid didn’t make its debut in the U.S. until 1992, but its triangular building blocks date back further.

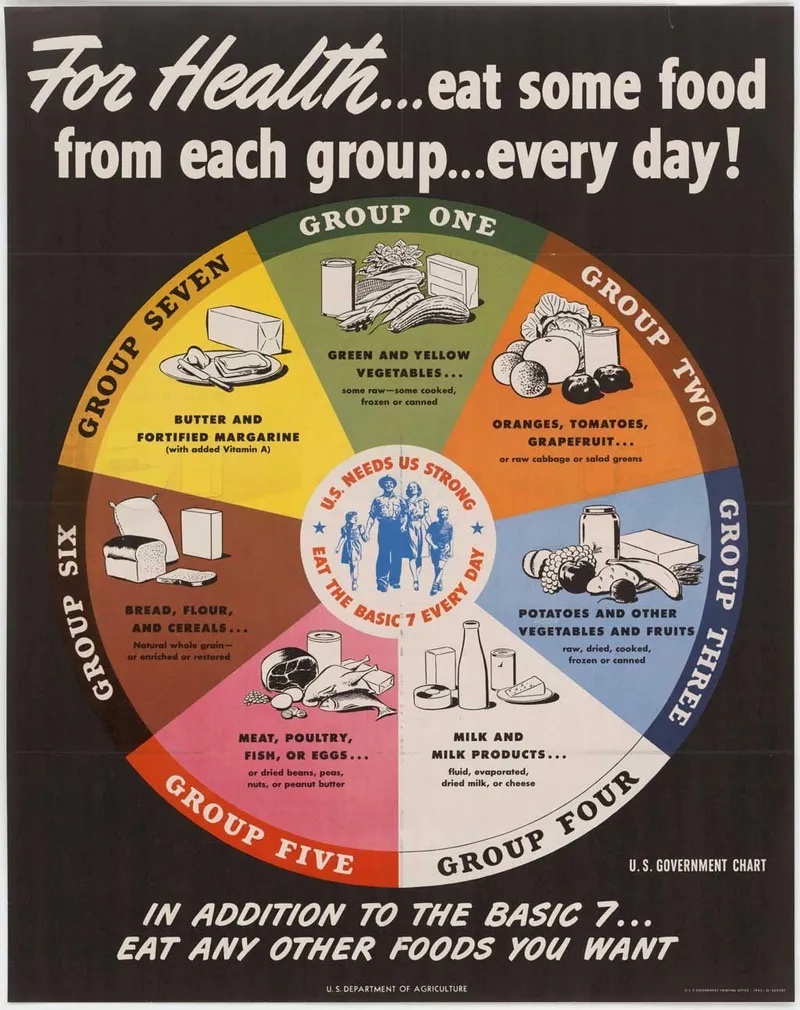

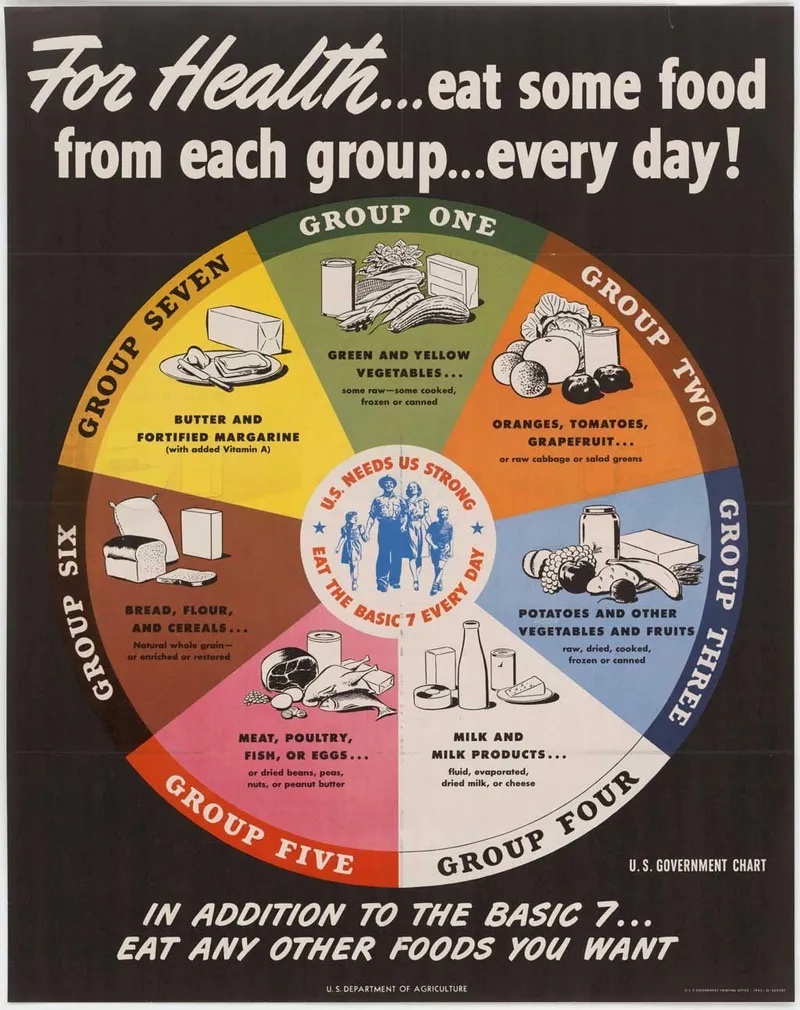

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “The Basic Seven,” 1943

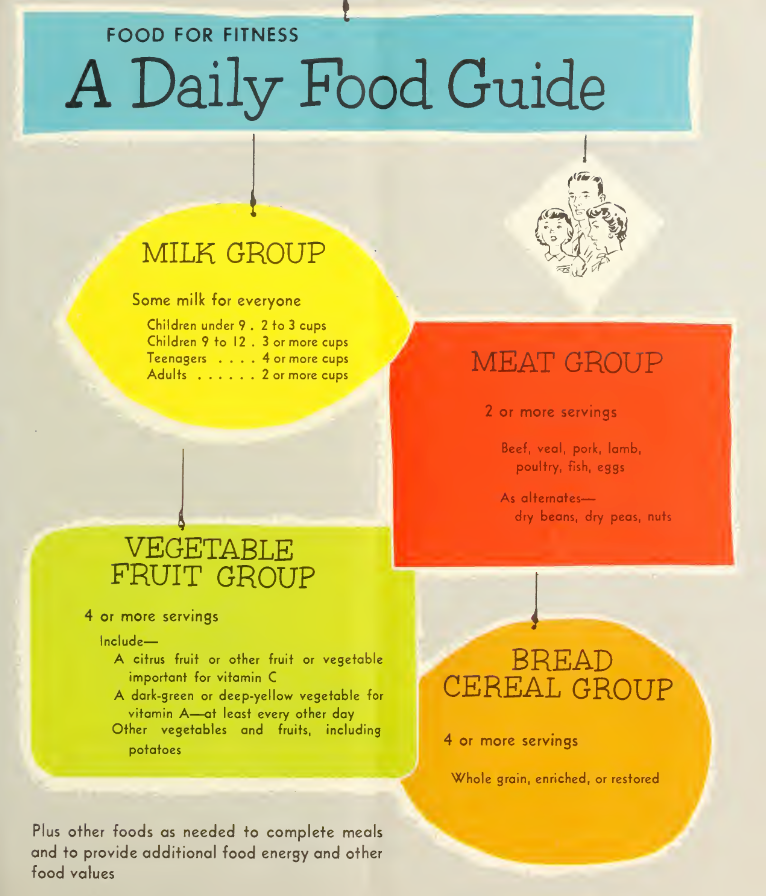

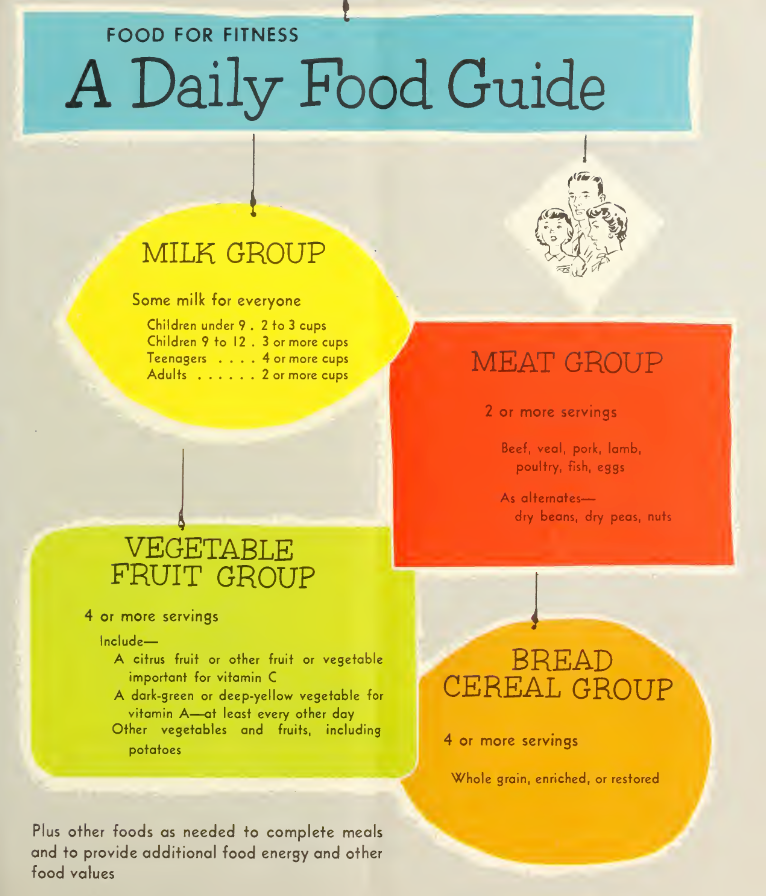

The U.S. Department of Agriculture published its first dietary guidance in 1894 as a “Farmers’ Bulletin.” Over the next 80 years, as nutrition and food science understanding evolved, the department issued new guidelines on how to eat. In 1933, guidance advised families on how to get nutrients on a Depression-era budget. In 1943, the USDA’s “Basic Seven” food groups focused on healthy eating during wartime rationing. In 1956, USDA simplified its guidance to the “Basic Four” food groups.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “The Basic Four,” 1956

Up until the mid-20th century, nutrition guidance focused on vitamin deficiencies and making sure Americans got enough of certain foods. But as chronic health problems like obesity and cardiovascular disease began to rise in the 1950s and ‘60s, so did concerns about the American menu

In 1980, the USDA and HHS released the first set of dietary guidelines, which the USDA now publishes every five years. The food pyramid and MyPlate are simple, visual representations of these 100-plus-page guidelines over the years.

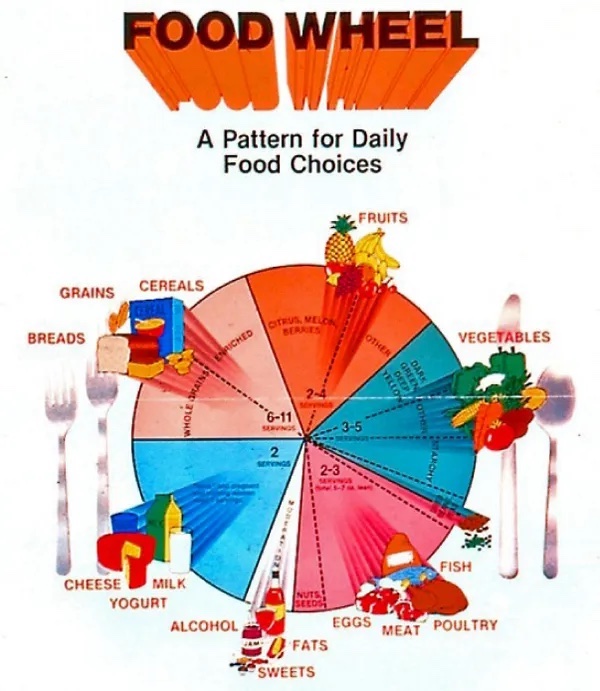

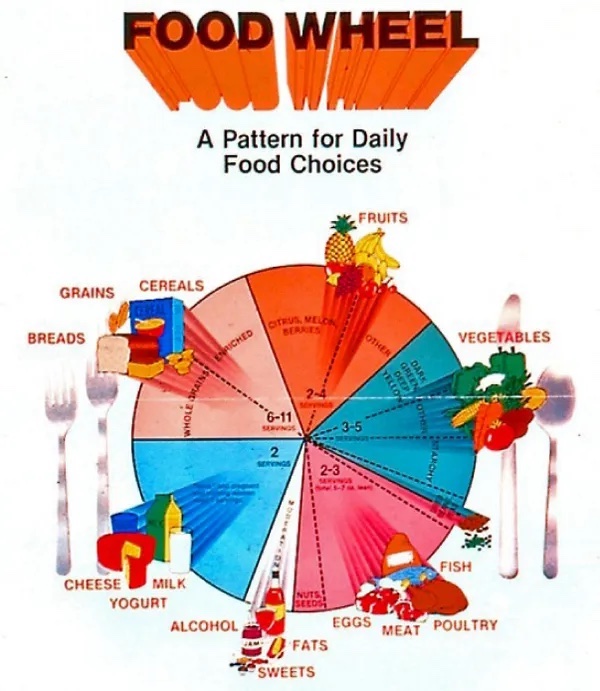

The dietary guidelines of the 1980s and 1990s focused heavily on reducing fats and cholesterol and eating more carbohydrates such as rice, corn and wheat.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Food Wheel,” 1984

“Carbohydrates are especially helpful in weight-reduction diets because, ounce for ounce, they contain about half as many calories as fats do,” read the 1985 dietary guide.

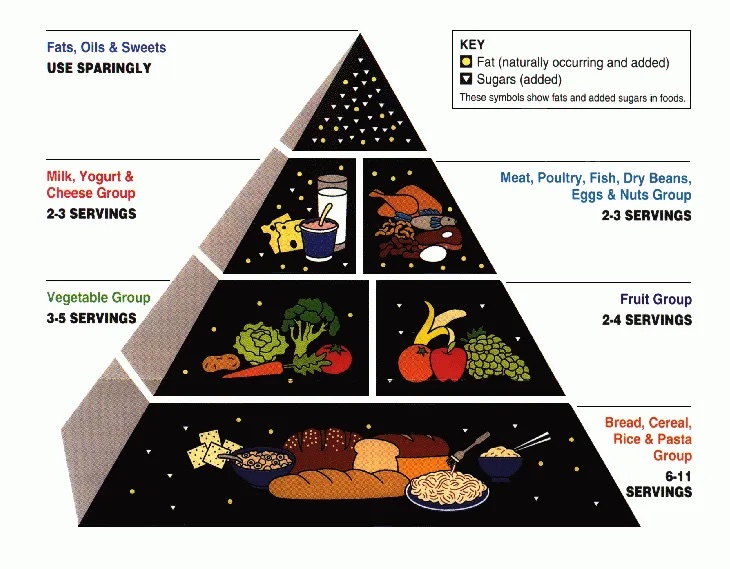

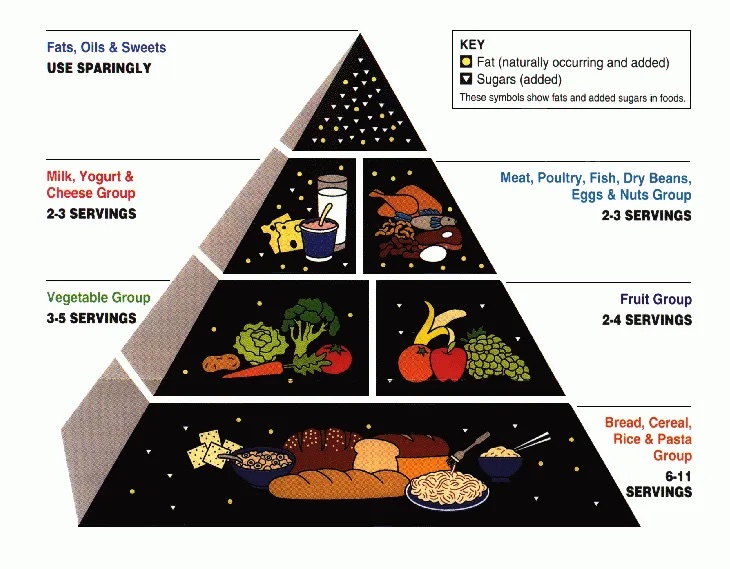

Fats, sugars and oils appeared at the 1992 Food Guide Pyramid’s top “use sparingly” category, and grains formed the base with a recommended six to 11 daily servings.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Food Guide Pyramid,” 1992

“The pyramid wasn’t ‘bad,’ but it reflected the nutrition science of its time,” said Debbie Petitpain, registered dietician and Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics spokesperson.

The thinking at the time was that low-fat diets were protective against heart disease, and carbohydrates were a healthier alternative to fatty foods. “It turned out that was wrong,” said Marlene Schwartz, University of Connecticut food policy and health professor.

Research around the turn of the century revealed the reality was more complicated. Added sugars and refined grains also contribute to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and not all fats are equally bad for us. “Unsaturated fats from foods like olives, nuts, and seeds can be protective for heart health,” Petitpain said.

Reflecting this shift, the 2005 dietary guidelines ditched the grain-heavy focus in favor of a more even breakdown across the food groups. For a 2,000-calorie diet, federal guidance recommended six ounces of grains (half of them whole grains), two and a half cups of vegetables, two cups of fruits, five and a half ounces of lean meat or beans and three cups of milk.

The USDA ditched the pyramid’s hierarchical sections in favor of vertical colored stripes and added a person walking up the side to represent physical activity. The visual was confusing and hard to parse.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “MyPyramid,” 2005

In search of a more intuitive graphic, the USDA changed to MyPlate in 2011. MyPlate focused on proportions as they might appear on a plate, broken up into roughly even quarters of fruit, vegetables, grains and protein. The underlying portion sizes haven’t changed since 2005.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “MyPlate,” 2011

Did the food pyramid change how Americans eat?

Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, Tufts University nutrition science professor, described the pyramid as a disaster. “People feared all fats, regardless of the type or the food source,” he said. “Refined grains and starches — which we now know have similar health effects as added sugar — were given a free pass.” Despite the pyramid being retired years ago, Mozaffarian said, “The image is burned into people’s minds, conscious and unconscious.”

The American diet shifted from the 1970s to the 2000s; fewer daily calories came from fat, and more calories came from carbs. Food manufacturers made more “low-fat” and “fat-free” options. “They sort of took the fat out of the cookies, but then they put in more sugar,” Schwartz said. “And so even though the grams of fat went down, the overall nutrition really wasn’t improved.”

The trend of less fat and more carbs has shown signs of reversing in more recent data post-2000, when “low-carb” diets took off. However, overall intake of both fats and carbs has climbed as Americans consume more calories overall, eat out more and consume more processed foods.

Not all experts blame the pyramid.

Schwartz said Americans’ finances tend to drive their dietary choices. “If you have a limited income and your goal is to feed your children, your dollars are going to go a lot farther with processed, packaged food than fresh ingredients,” she said.

Research since 1980 shows Americans have regularly failed to eat according to recommended dietary guidelines. “The pyramid definitely shaped nutrition education and public awareness,” Petitpain said, “but its effect on actual eating habits was limited.”

Surveys show only about one-third of American adults have heard of MyPlate and even fewer have tried to follow its recommendations.

Public school lunch programs have been required since 2010 to follow MyPlate guidelines and the dietary guidelines can shape federal food programs like WIC.

It’s not clear whether December’s federal dietary guidelines release will include a plan to replace MyPlate and its diet recommendations.

What is a healthy, balanced diet?

In a media world inundated by fad diets, supplements and cures, knowing what is healthy can feel overwhelming. The nutrition experts we spoke with offered broad guidance, most of which you have probably heard before.

A healthy diet is varied but includes generous portions of fruits and veggies alongside whole grains, beans, nuts and lean protein. Cheese, milk, poultry, eggs and unprocessed red meats should be consumed in moderation.

“Modern nutrition advice emphasizes eating patterns rather than single nutrients,” Petitpain said.

Cutting out any of the macronutrients food groups like carbs or fats might cause weight loss, because you may be eating less food overall, but it is hard to sustain and won’t be healthy in the long run, Schwartz said.

Experts said MyPlate isn’t a bad place to start.

PolitiFact Researcher Caryn Baird contributed to this report.