The American Medical Association passed a resolution encouraging hospitals to offer healthy plant-based food options.

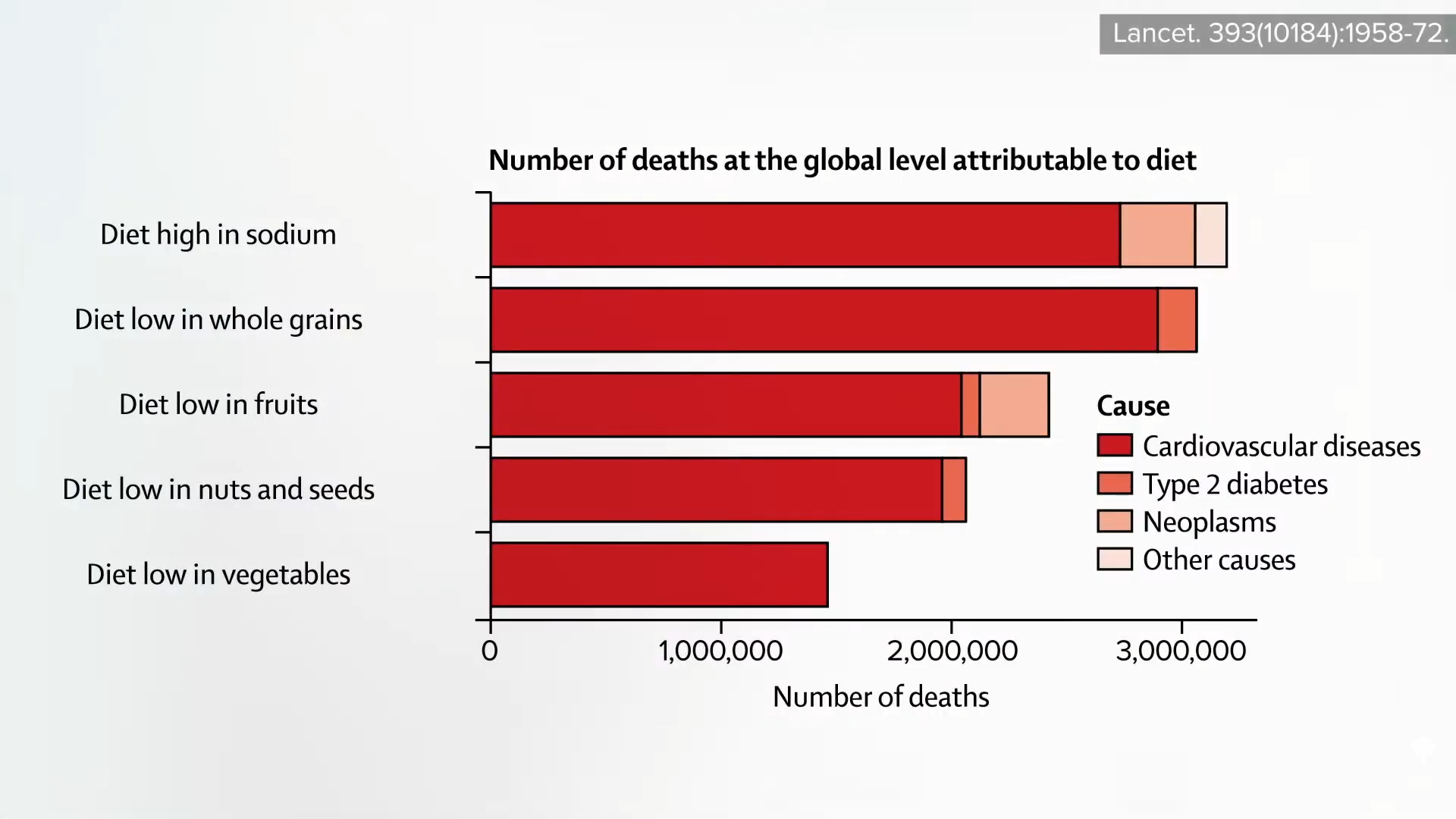

“Globally, 11 million deaths annually are attributable to dietary factors, placing poor diet ahead of any other risk factor for death in the world.” Given that diet is our leading killer, you’d think that nutrition education would be emphasized during medical school and training, but there is a deficiency. A systematic review found that, “despite the centrality of nutrition to a healthy lifestyle, graduating medical students are not supported through their education to provide high-quality, effective nutrition care to patients…”

It could start in undergrad. What’s more important? Learning about humanity’s leading killer or organic chemistry?

In medical school, students may average only 19 hours of nutrition out of thousands of hours of instruction, and they aren’t even being taught what’s most useful. How many cases of scurvy and beriberi, diseases of dietary deficiency, will they encounter in clinical practice? In contrast, how many of their future patients will be suffering from dietary excesses—obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease? Those are probably a little more common than scurvy or beriberi. “Nevertheless, fully 95% of cardiologists [surveyed] believe that their role includes personally providing patients with at least basic nutrition information,” yet not even one in ten feels they have an “expert” grasp on the subject.

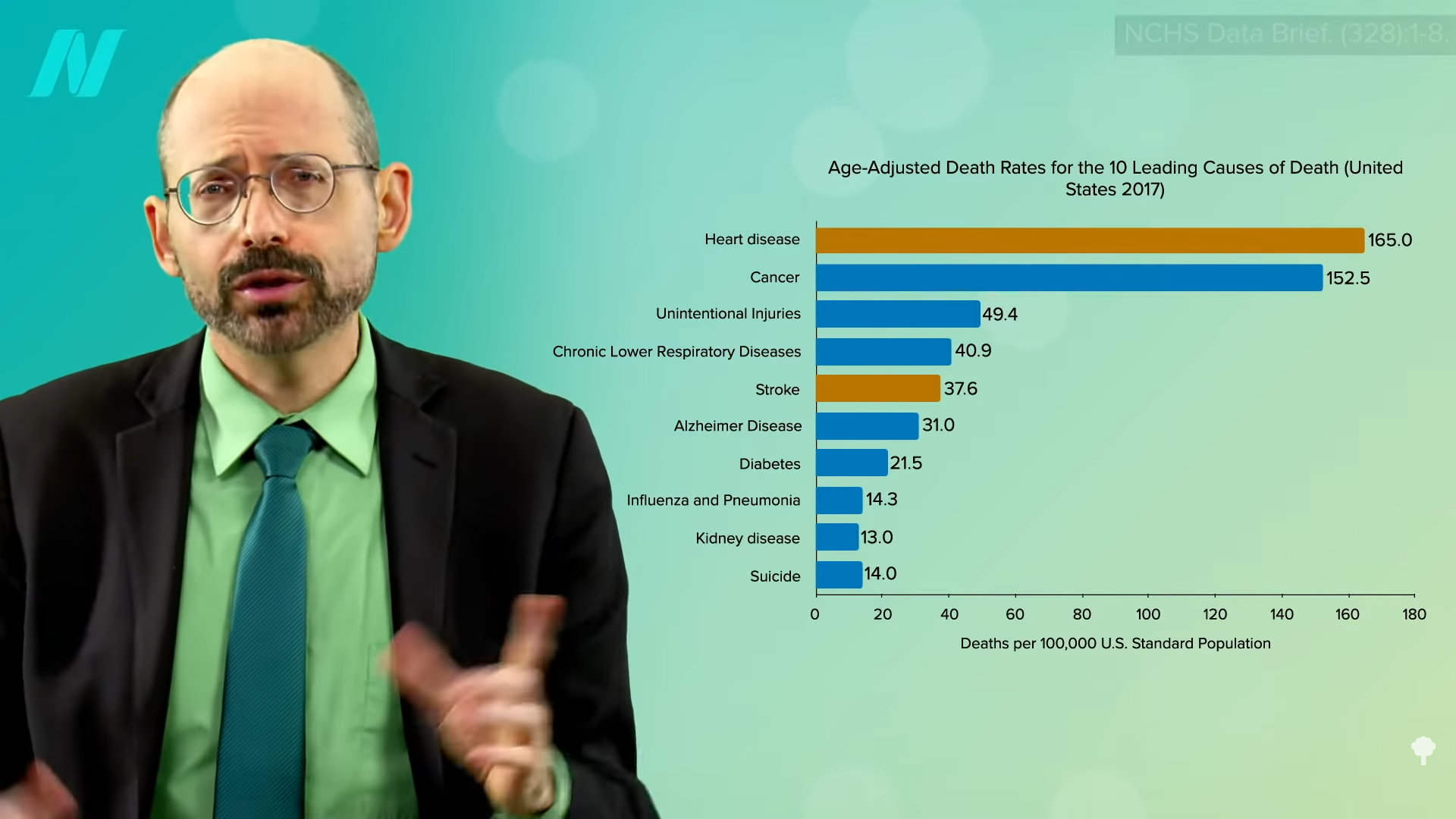

If you look at the clinical guidelines for what we should do for our patients with regard to our number one killer, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, all treatment begins with a healthy lifestyle, as shown below and at 1:50 in my video Hospitals with 100-Percent Plant-Based Menus.

“Yet, how can clinicians put these guidelines into practice without adequate training in nutrition?”

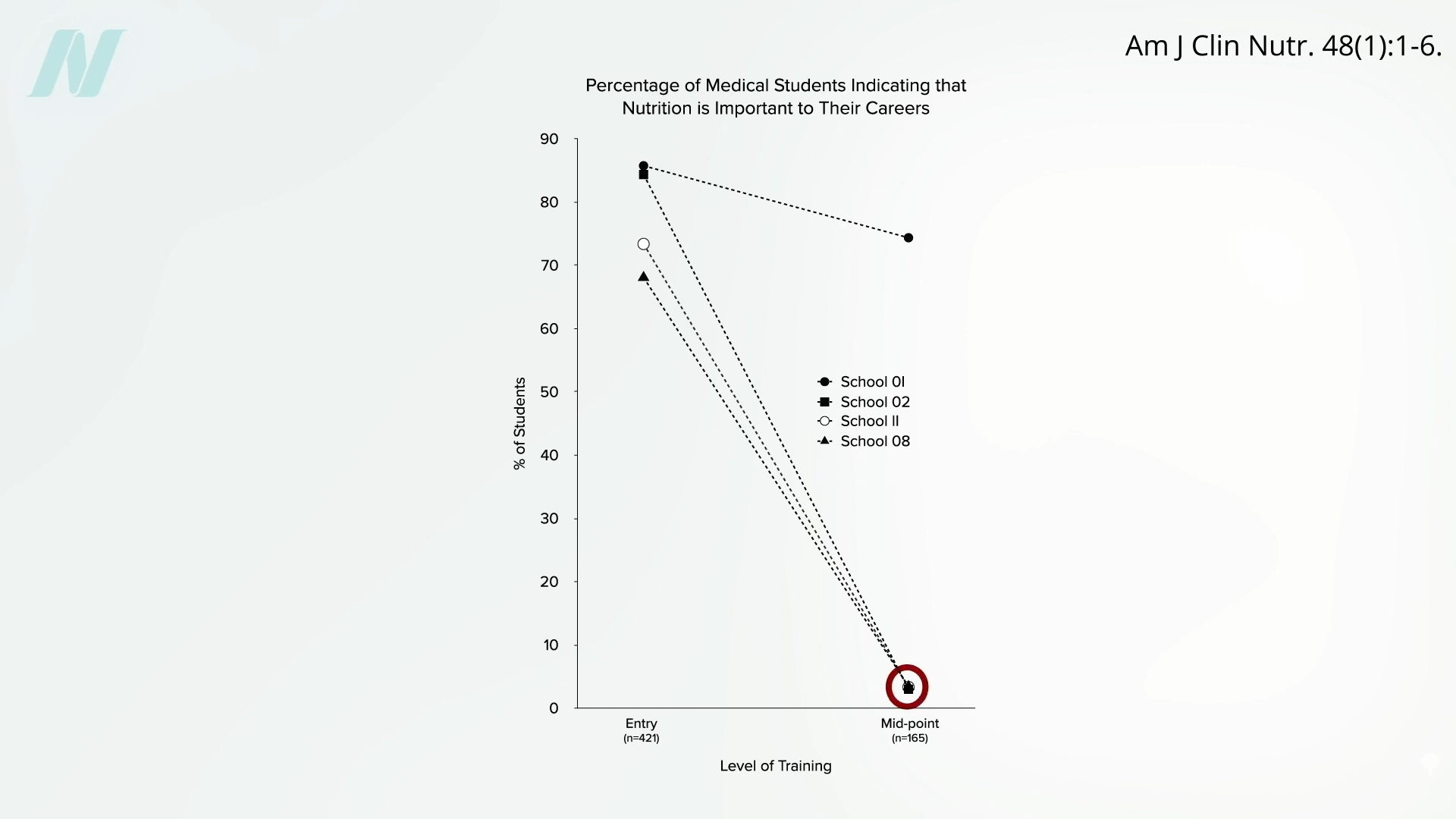

Less than half of medical schools report teaching any nutrition in clinical practice. In fact, they may be effectively teaching anti-nutrition, as “students typically begin medical school with a greater appreciation for the role of nutrition in health than when they leave.” Below and at 2:36 in my video is a figure entitled “Percentage of Medical Students Indicating that Nutrition is Important to Their Careers.” Upon entry to different medical schools, about three-quarters on average felt that nutrition is important to their careers. Smart bunch. Then, after two years of instruction, they were asked the same question, and the numbers plummeted. In fact, at most schools, it fell to 0%. Instead of being educated, they got de-educated. They had the notion that nutrition is important washed right out of their brains. “Thus, preclinical teaching”— the first two years of medical school—“engenders a loss of a sense of the relevance of the applied discipline of nutrition.”

Following medical school, during residency, nutrition education is “minimal or, more typically, absent.” “Major updates” were released in 2018 for residency and fellowship training requirements, and there were zero requirements for nutrition. “So you could have an internal medicine graduate who comes out of a terrific program and has learned nothing—literally nothing—about nutrition.”

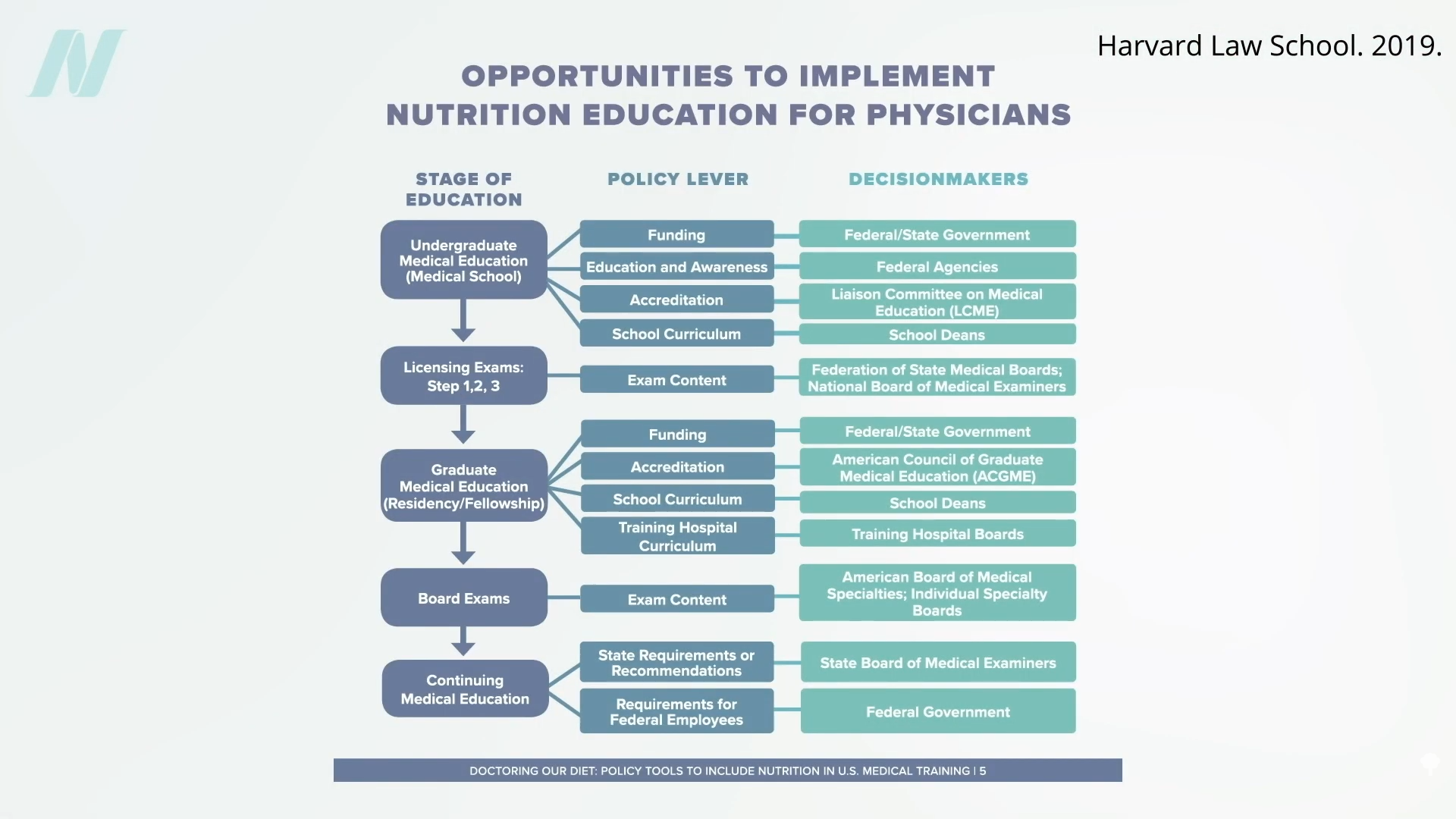

“Why is diet not routinely addressed in both medical education and practice already, and what should be done about that?” One of the “reasons for the medical silence in nutrition” is that, “sadly…nutrition takes a back seat…because there are few financial incentives to support it.” What can we do about that? The Food Law and Policy Clinic at Harvard Law School identified a dozen different policy levers at all stages of medical education and the kinds of policy recommendations there could be for the decision-makers, as you can see here and at 3:48 in my video.

For instance, the government could require doctors working for Veterans Affairs (VA) to get at least some courses in nutrition, or we could put questions about nutrition on the board exams so schools would be pressured to teach it. As we are now, even patients who have just had a heart attack aren’t changing their diet. Doctors may not be telling them to do so, and hospitals may be actively undermining their future with the food they serve.

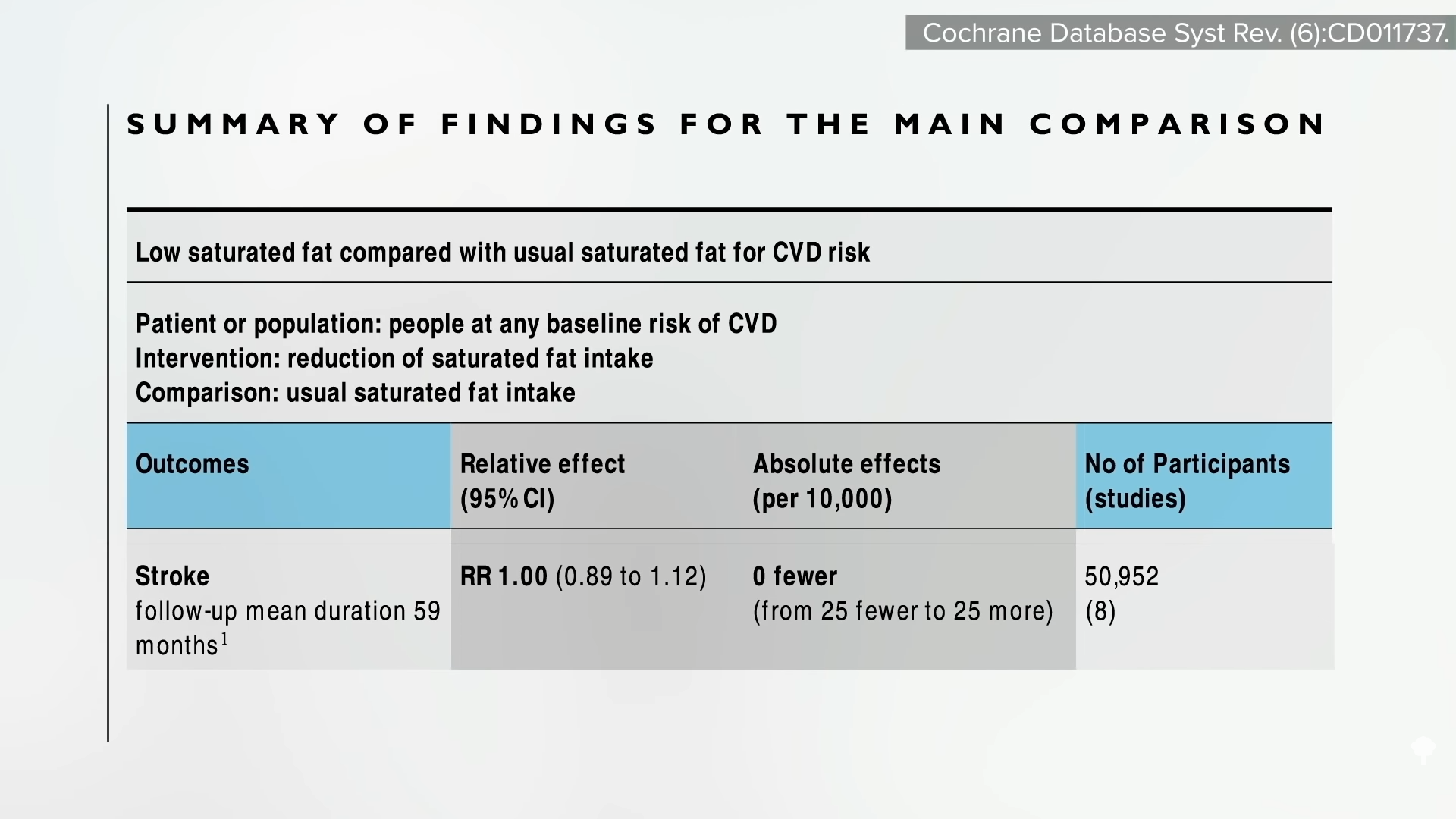

The good news is that the American Medical Association (AMA) has passed a resolution encouraging hospitals to offer healthy food options. What a concept! “Our AMA hereby calls on [U.S.] Health Care Facilities to improve the health of patients, staff, and visitors by: (a) providing a variety of healthy food, including plant-based meals, and meals that are low in saturated and trans fat, sodium, and added sugars; (b) eliminating processed meats from menus; and (c) providing and promoting healthy beverages.” Nice!

“Similarly, in 2018, the State of California mandated the availability of plant-based meals for hospital patients,” and there are hospitals in Gainesville (FL), the Bronx, Manhattan, Denver, and Tampa (FL) that “all provide 100% plant-based meals to their patients on a separate menu and provide educational materials to inpatients to improve education on the role of diet, especially plant-based diets, in chronic illness.”

Let’s check out some of their menu offerings: How about some lentil Bolognese? Or a cauliflower scramble with baked hash browns for breakfast, mushroom ragu for lunch, and, for supper, white bean stew, salad, and fruit for dessert. (This is the first time a hospital menu has ever made me hungry!)

The key to these transformations was “having a physician advocate and increasing education of staff and patients on the benefits of eating more plant-based foods.” A single clinician can spark change in a whole system, because science is on their side. “Doctors have a unique position in society” to influence policy at all levels; it’s about time we used it.

For more on the ingrained ignorance of basic clinical nutrition in medicine, see the related posts below.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link

Medically-supervised fasting has

Medically-supervised fasting has “

“