Just because you’re eating a vegetarian or vegan diet doesn’t mean you’re eating healthfully.

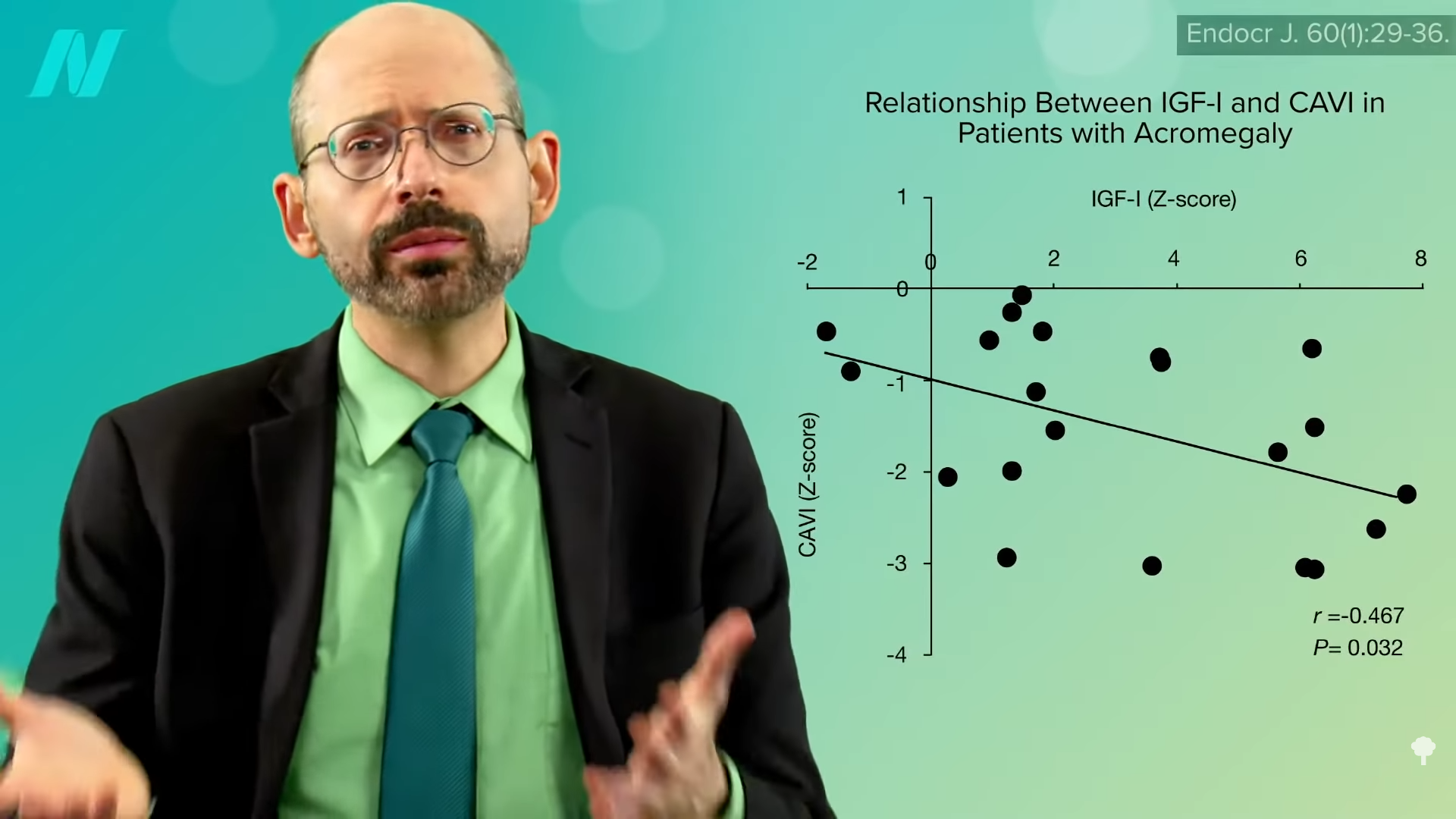

“Plant-Based Diets Are Associated with a Lower Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality in a General Population of Middle-Aged Adults”: This study of a diverse sample of 12,000 Americans found that “progressively increasing the intake of plant foods by reducing the intake of animal foods is associated with benefits on cardiovascular health and mortality.” Still, regarding plant-based diets for cardiovascular disease prevention, “all plant foods are not created equal.” As you can see in the graph below and at 0:40 in my video Vegetarians and Stroke Risk Factors: Vegan Junk Food?, a British study found higher stroke risk in vegetarians. Were they just eating a lot of vegan junk food?

“Any diet devoid of animal food sources can be claimed to be a vegetarian [or vegan] diet; thus, it is important to determine” what is being eaten. One of the first things I look at when I’m trying to see how serious a population is about healthy eating is something that is undeniably, uncontroversially bad: soda, aka liquid candy. Anyone drinking straight sugar water doesn’t have health on top of mind.

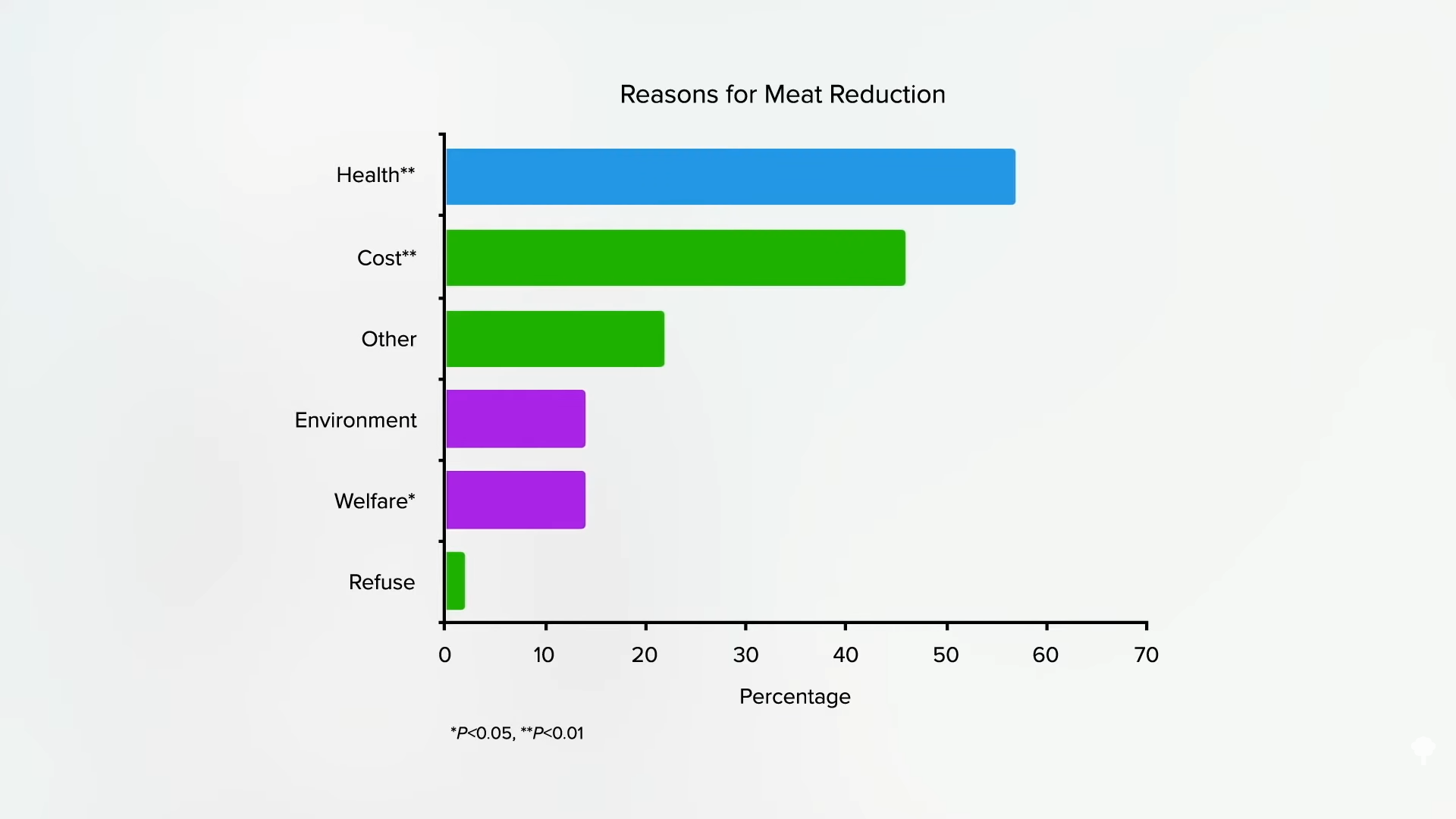

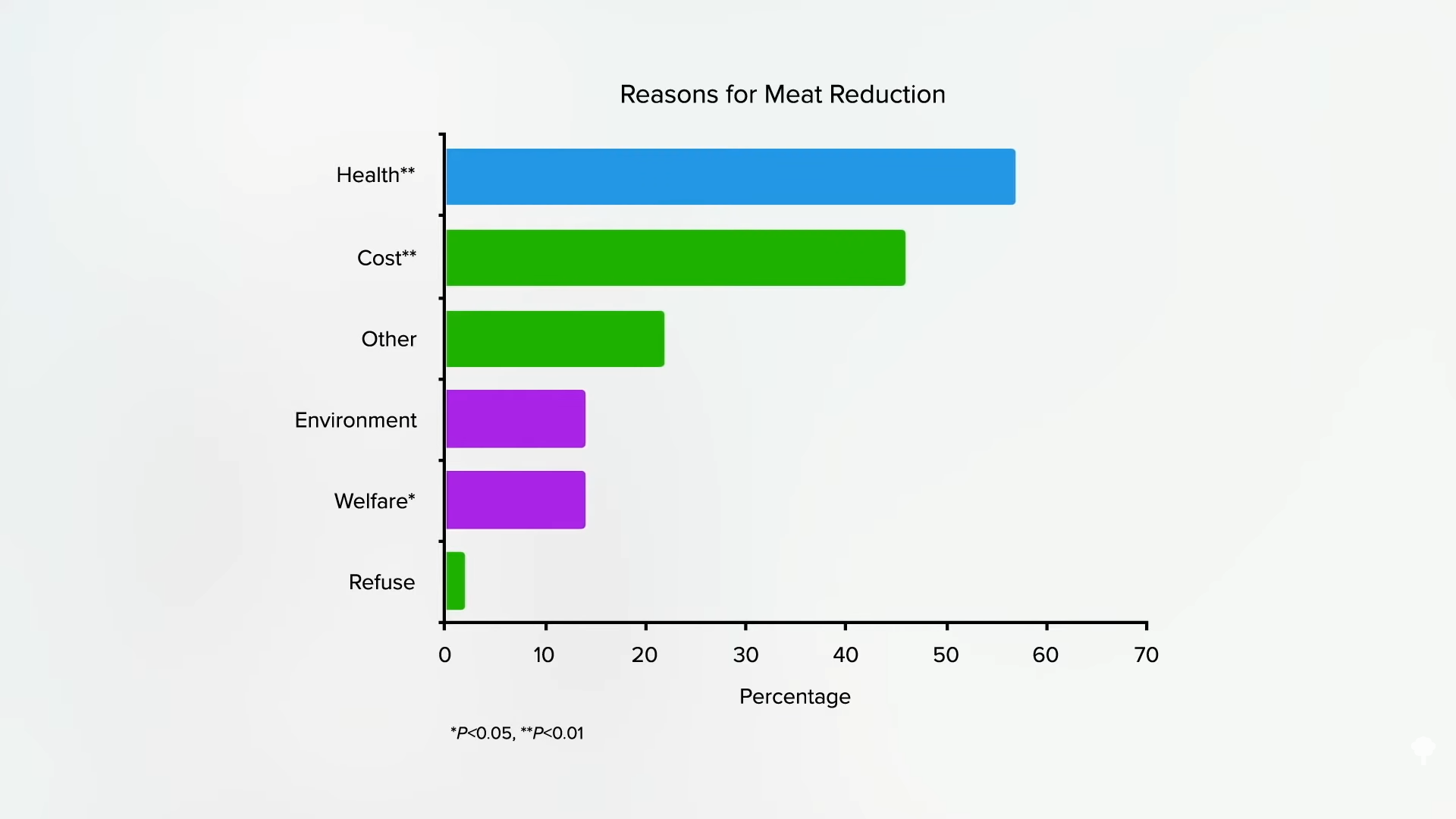

A large study was conducted of plant-based eaters in the United States, where people tend to cut down on meat for health reasons far more than for ethics, as you can see in the graph below and at 1:20 in my video.

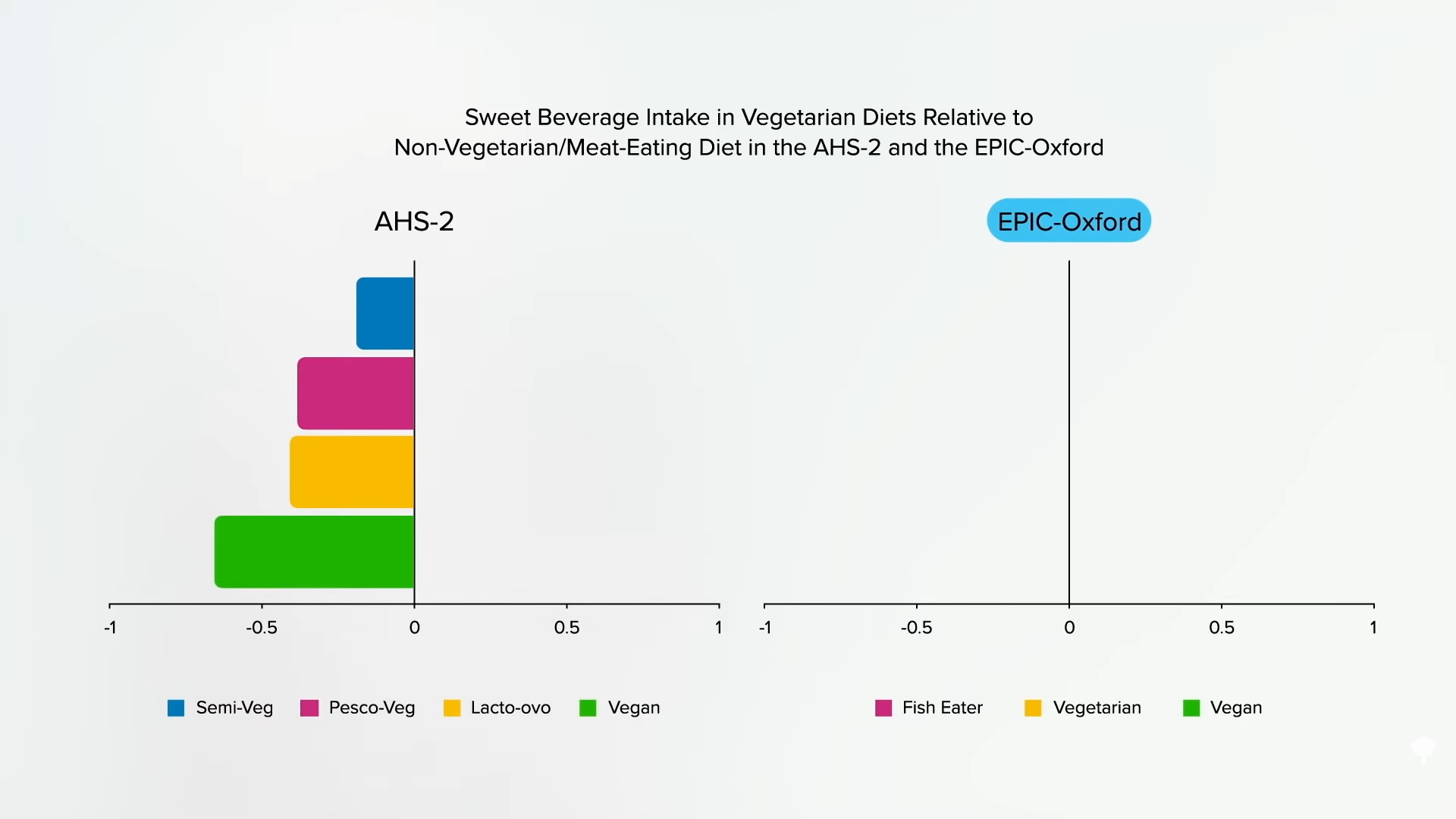

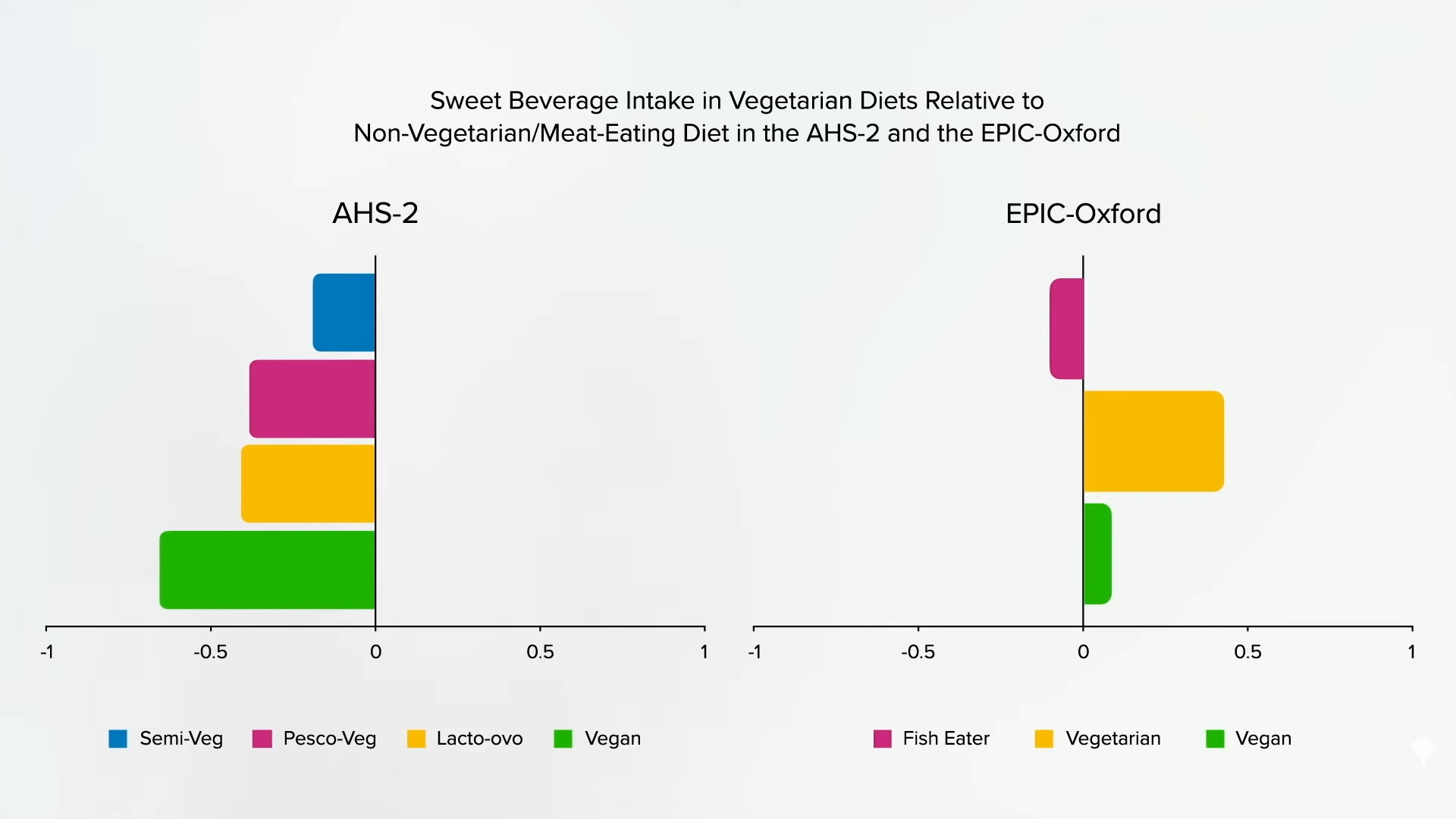

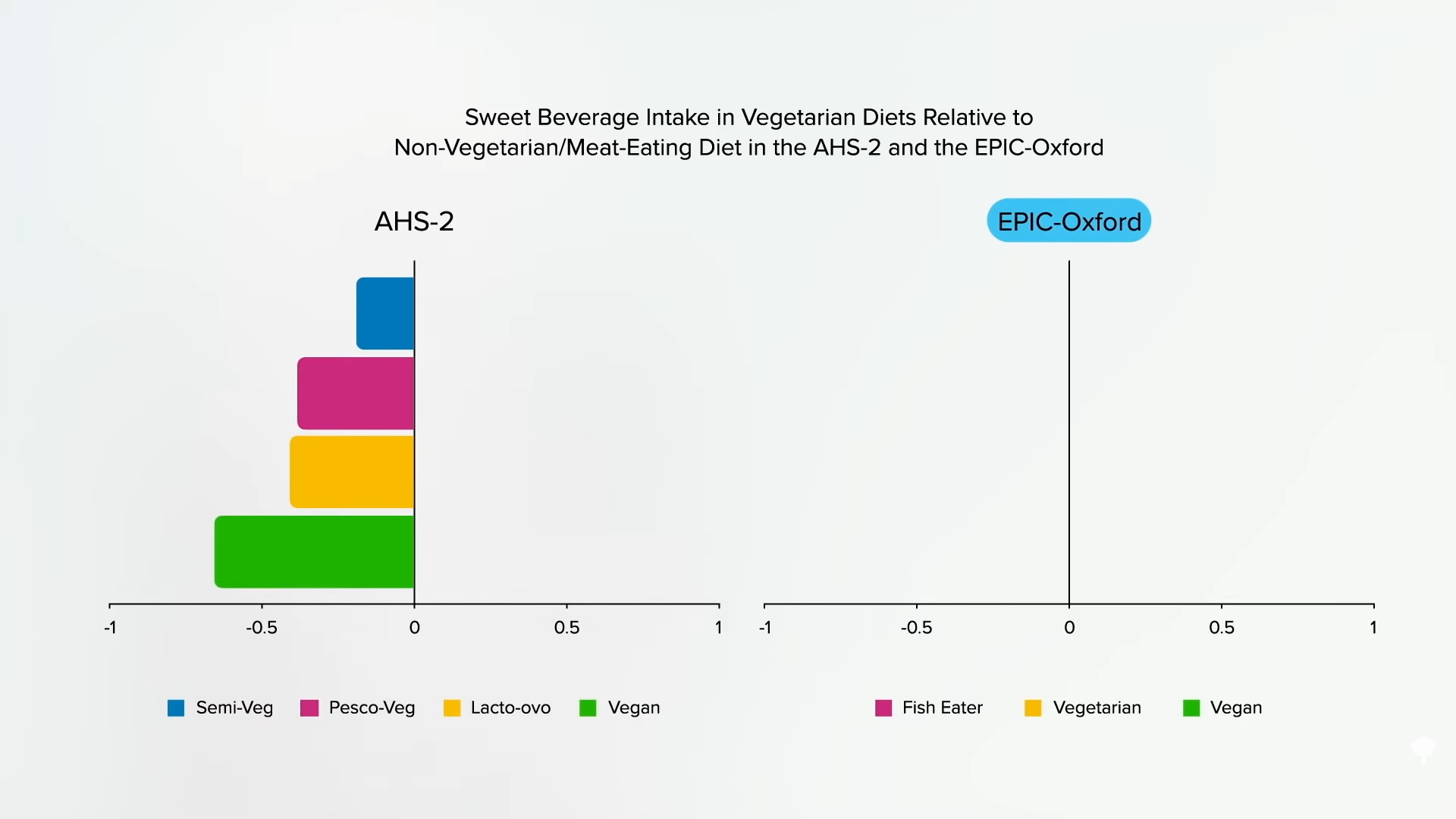

Researchers found that flexitarians drink fewer sugary beverages than regular meat eaters, as do pescatarians, vegetarians, and vegans, as you can see below and at 1:30.

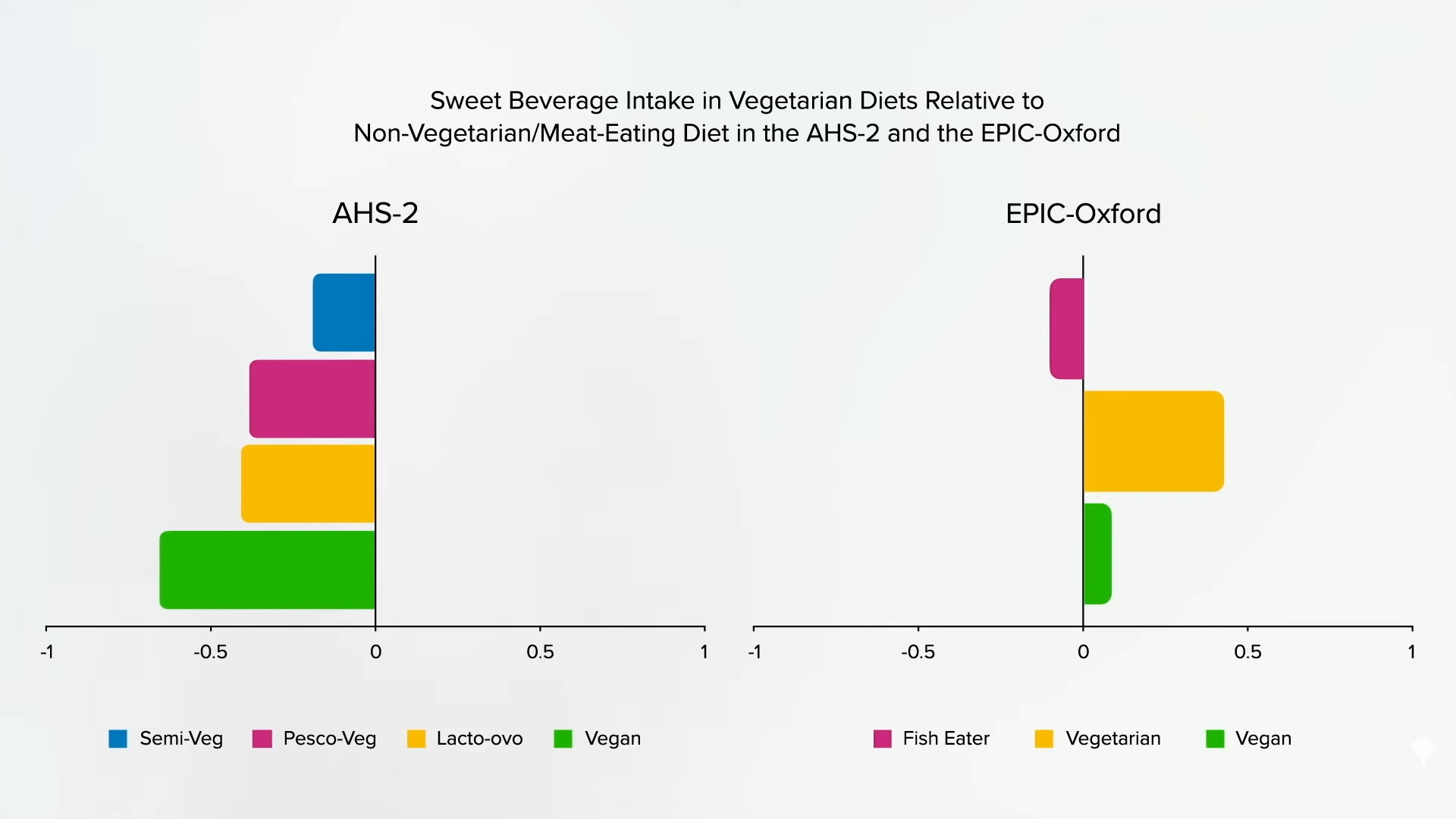

However, in the study from the United Kingdom where the increased stroke risk in vegetarians was found and where people are more likely to go veg or vegan for ethical reasons, researchers found that pescatarians drink less soda, but the vegetarians and vegans drink more, as shown in the graph below and at 1:44.

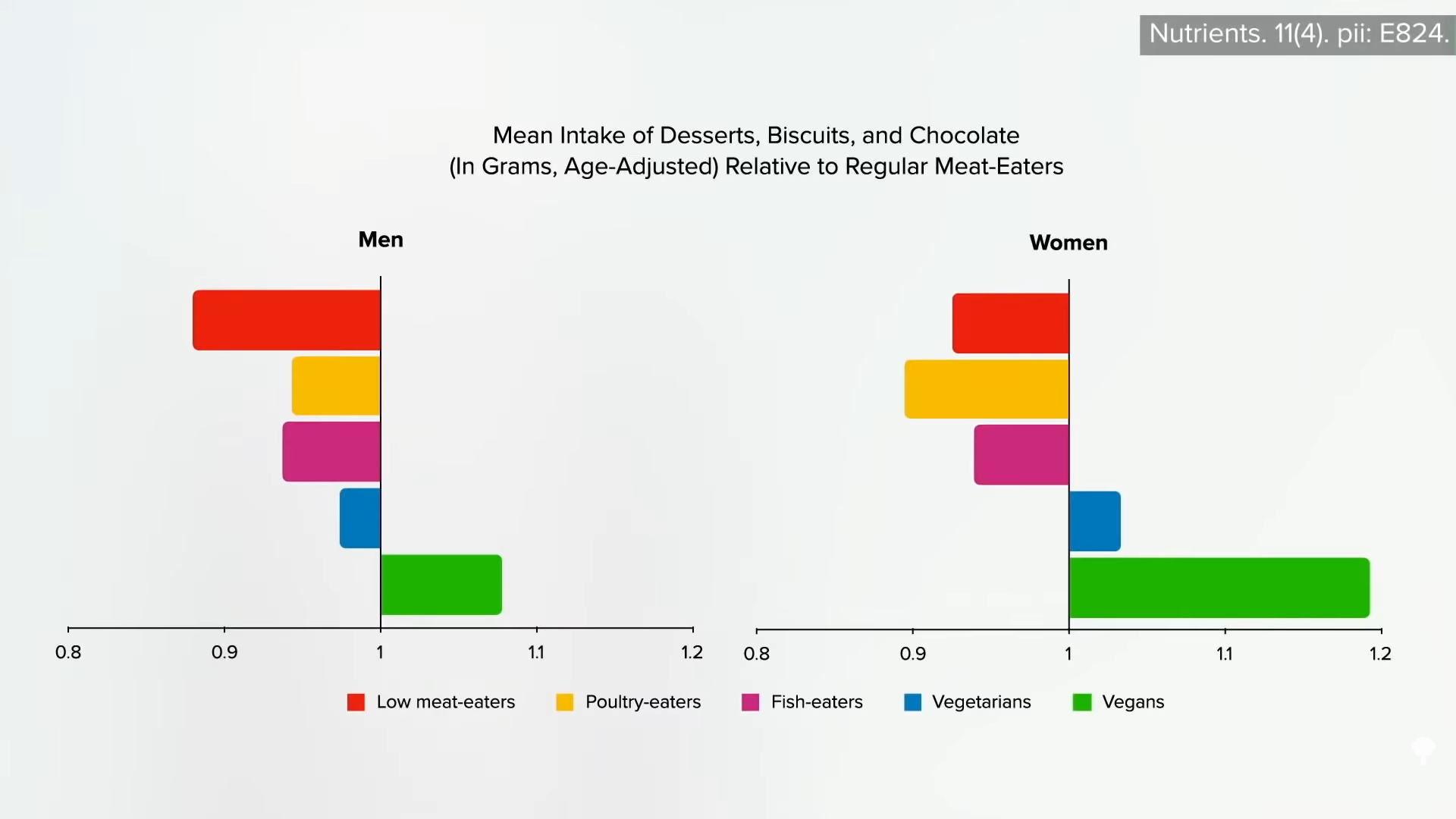

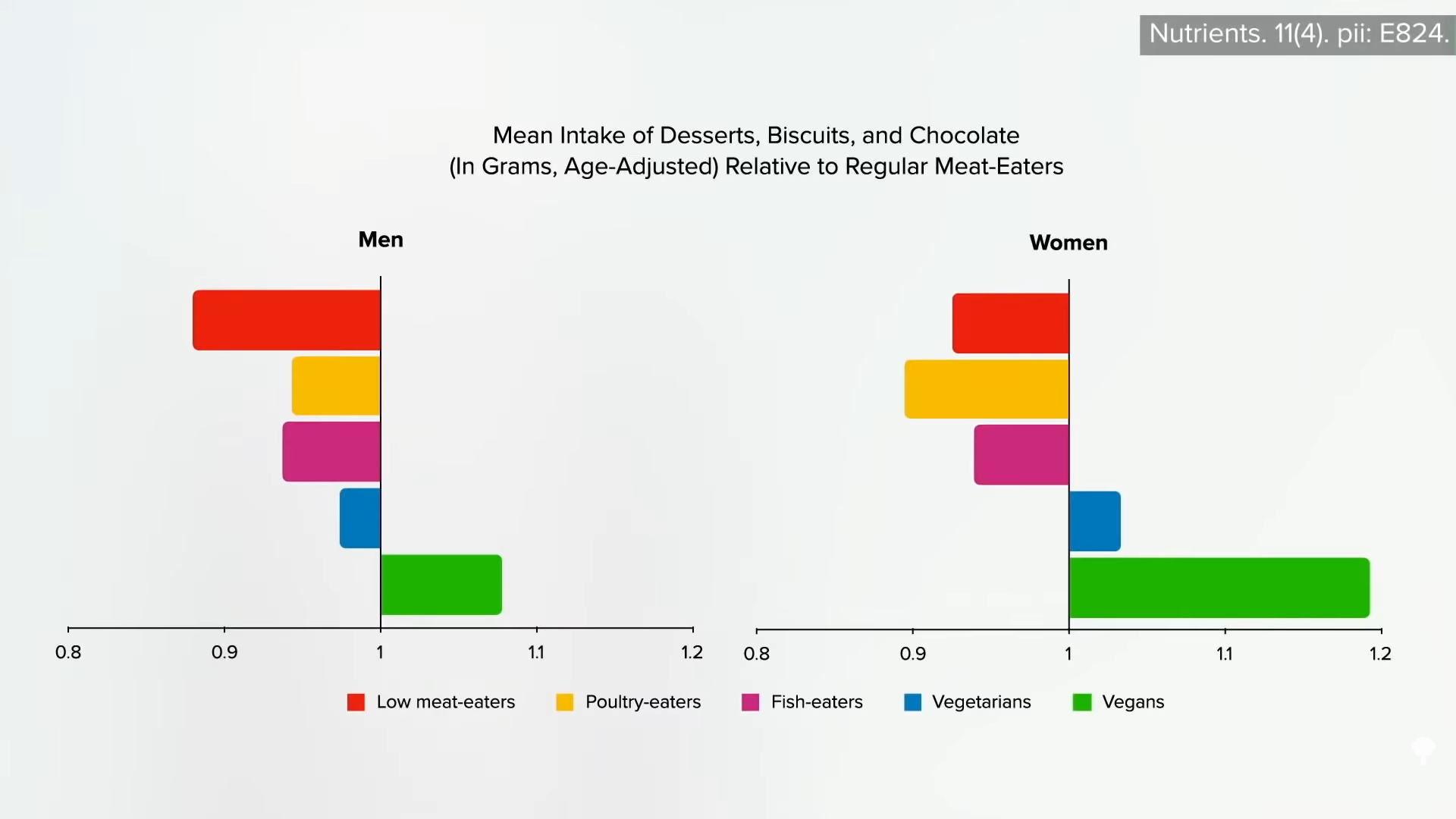

I’m not saying that’s why they had more strokes; it might just give us an idea of how healthfully they were eating. In the UK study, the vegetarian and vegan men and women ate about the same amounts of desserts, cookies, and chocolate, as you can see in the graph below and at 1:53.

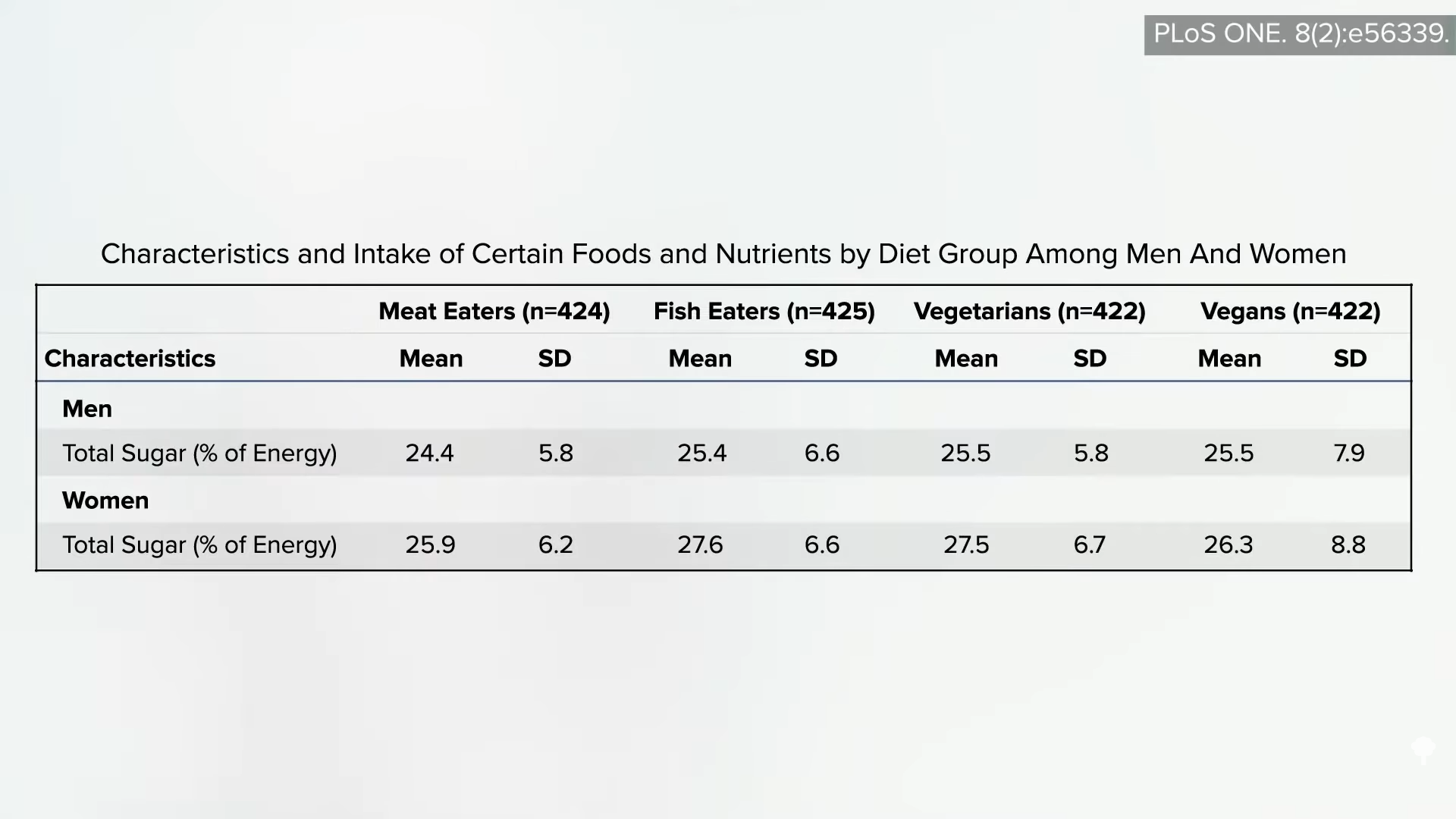

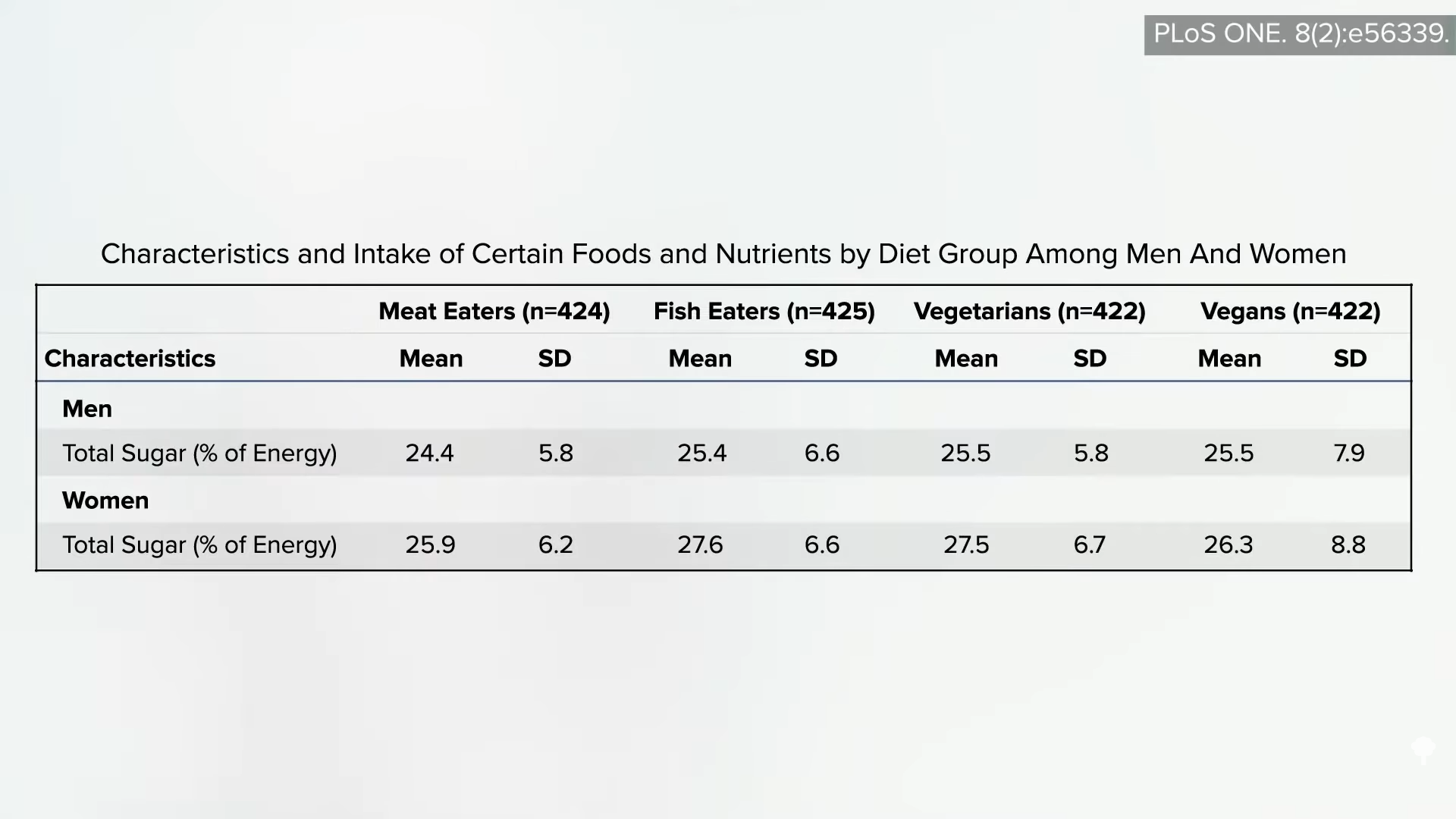

They also consumed about the same total sugar, as shown below and at 2:02.

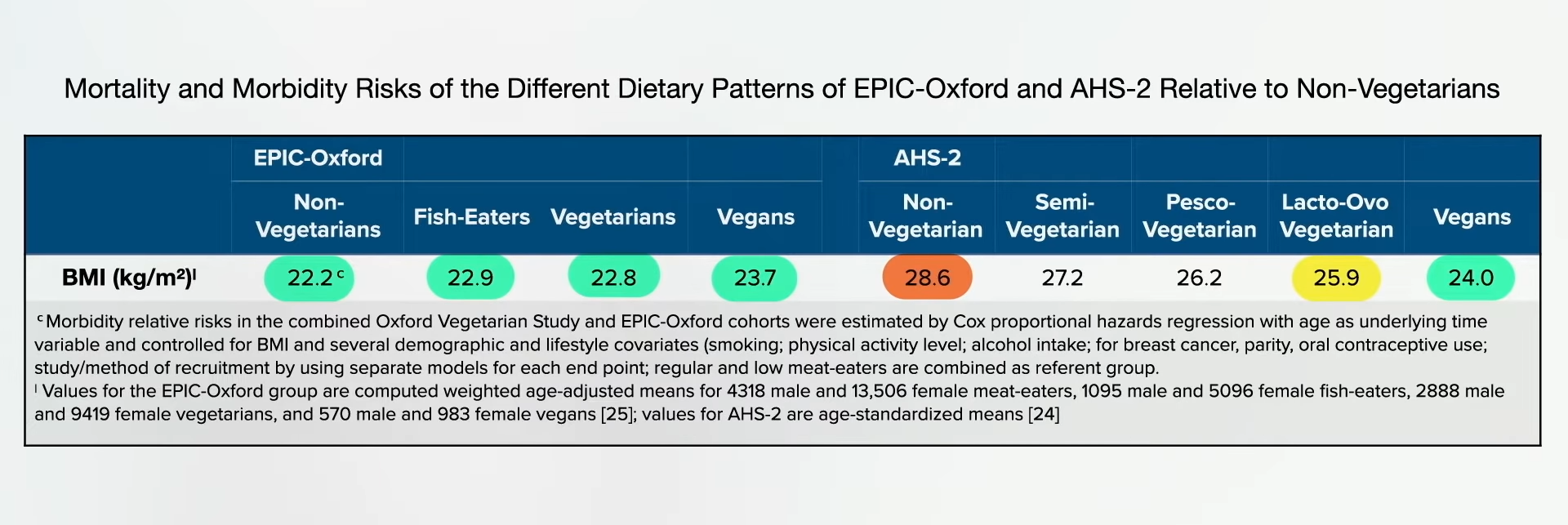

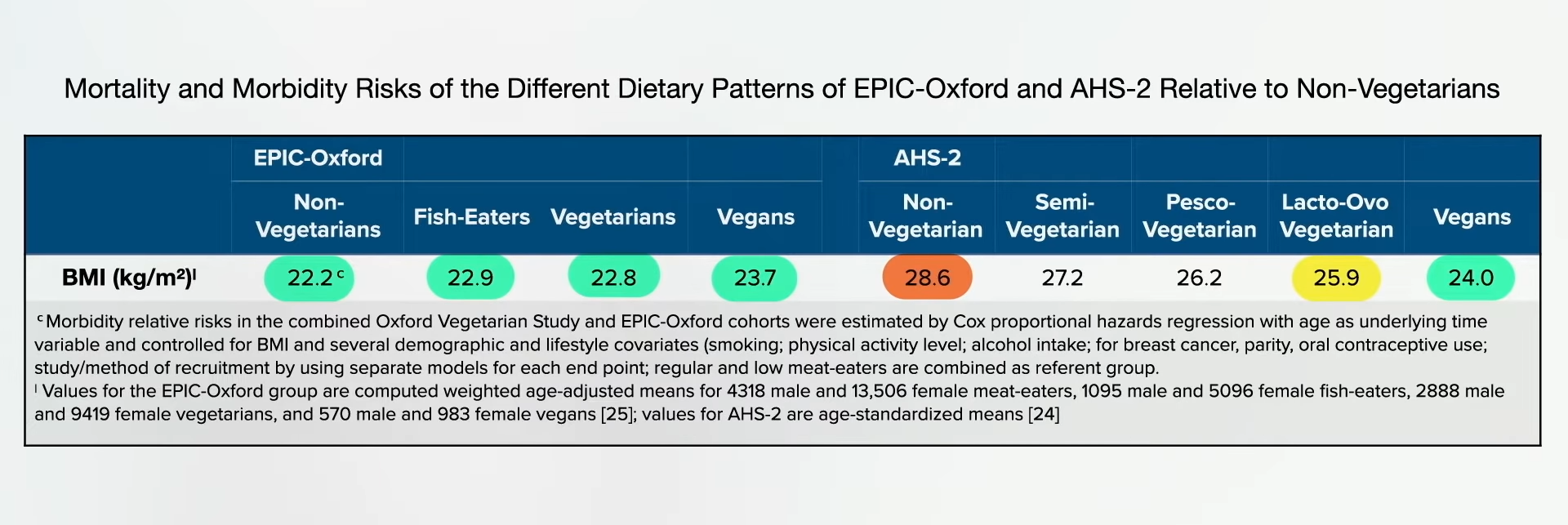

In the U.S. study, the average non-vegetarian is nearly obese, the vegetarians are a little overweight, and the vegans were the only ideal weight group. In this analysis of the UK study, however, everyone was about the same weight. The meat eaters were lighter than the vegans, as you can see below, and at 2:19 in my video. The EPIC-Oxford study seems to have attracted a particularly “health-conscious” group of meat eaters weighing substantially less than the general population.

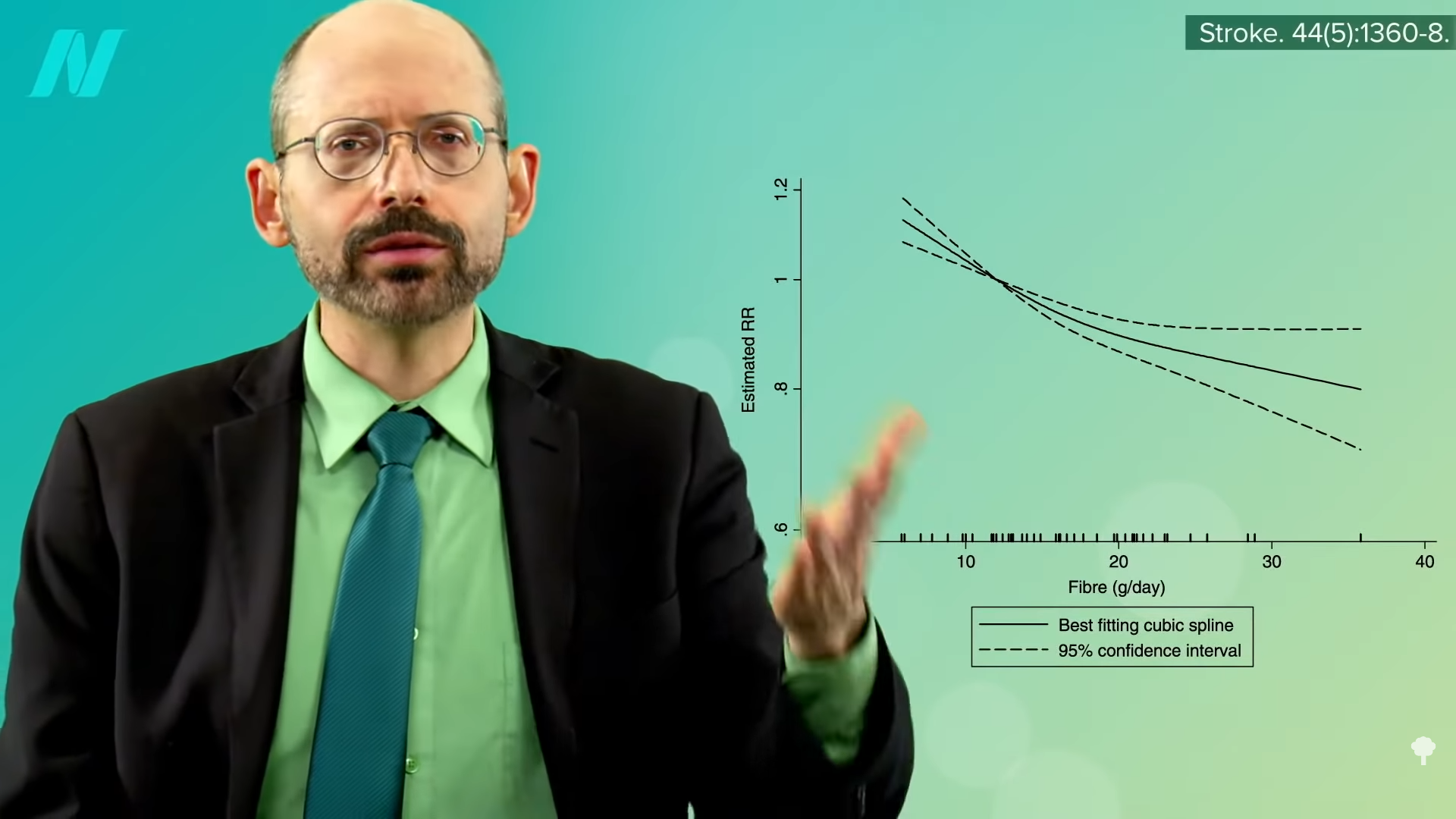

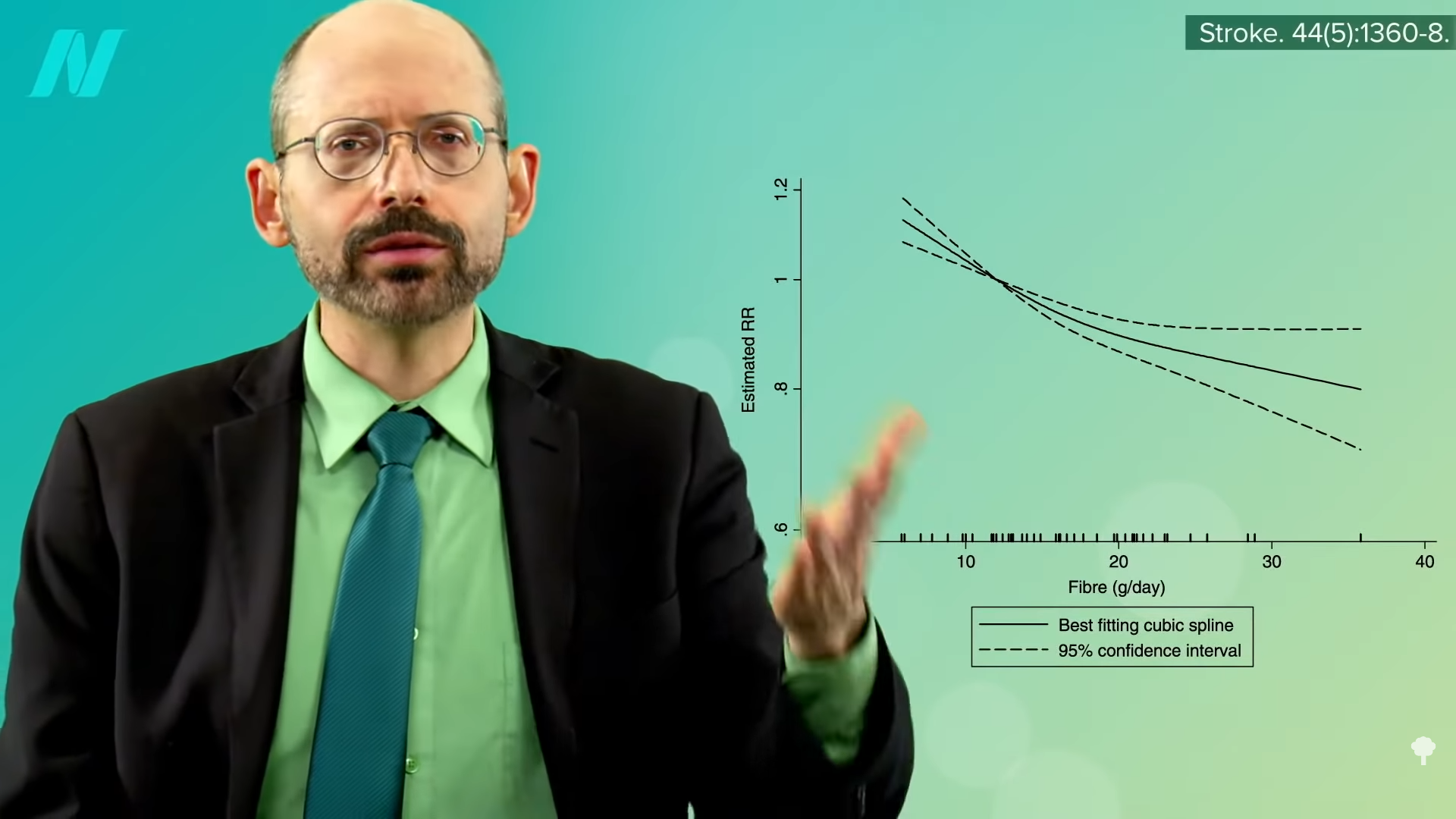

Let’s look at some specific stroke-related nutrients. Dietary fiber appears to be beneficial for the prevention of cardiovascular disease, including stroke, and it seems the more, the better, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:43 in my video.

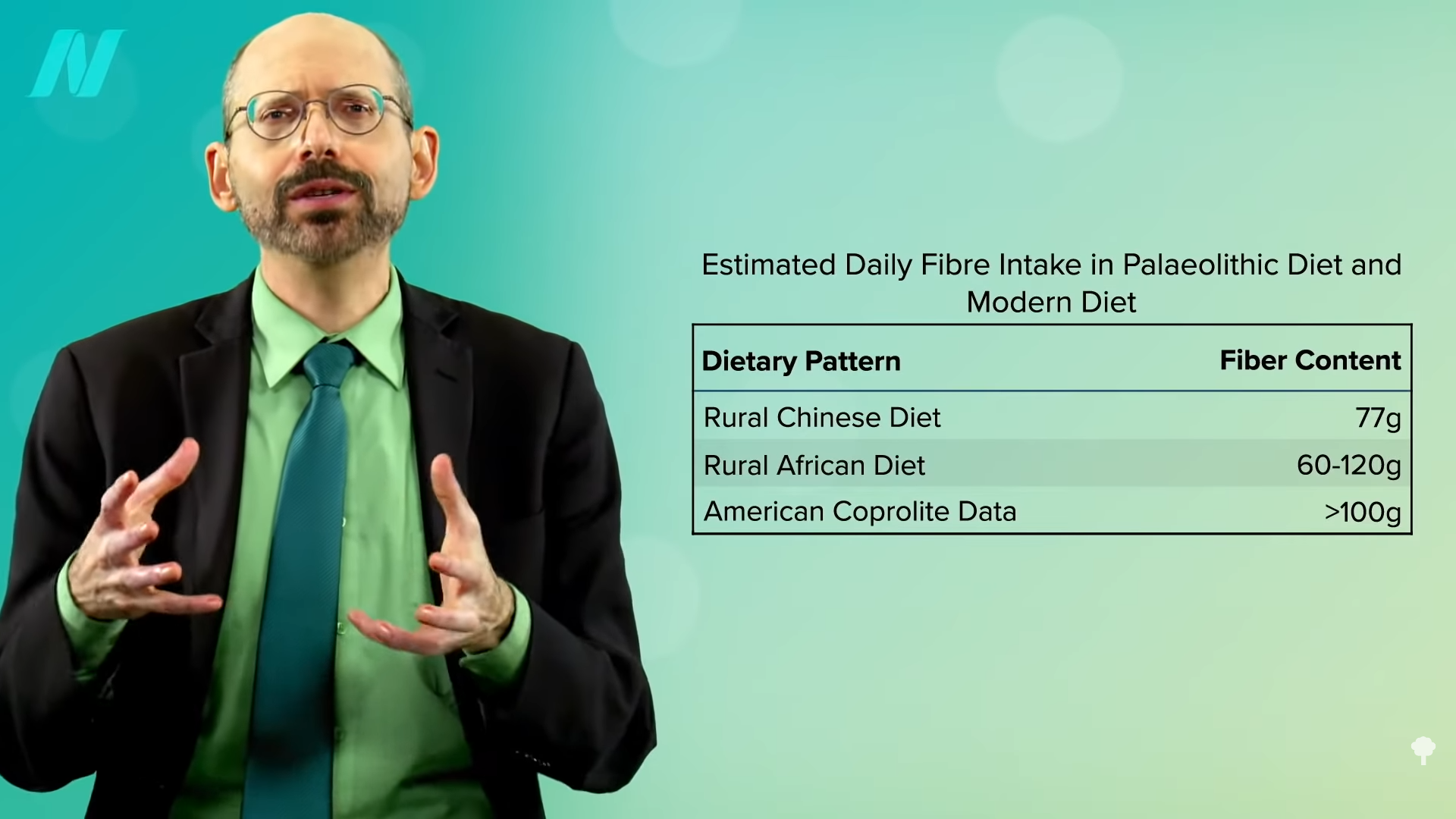

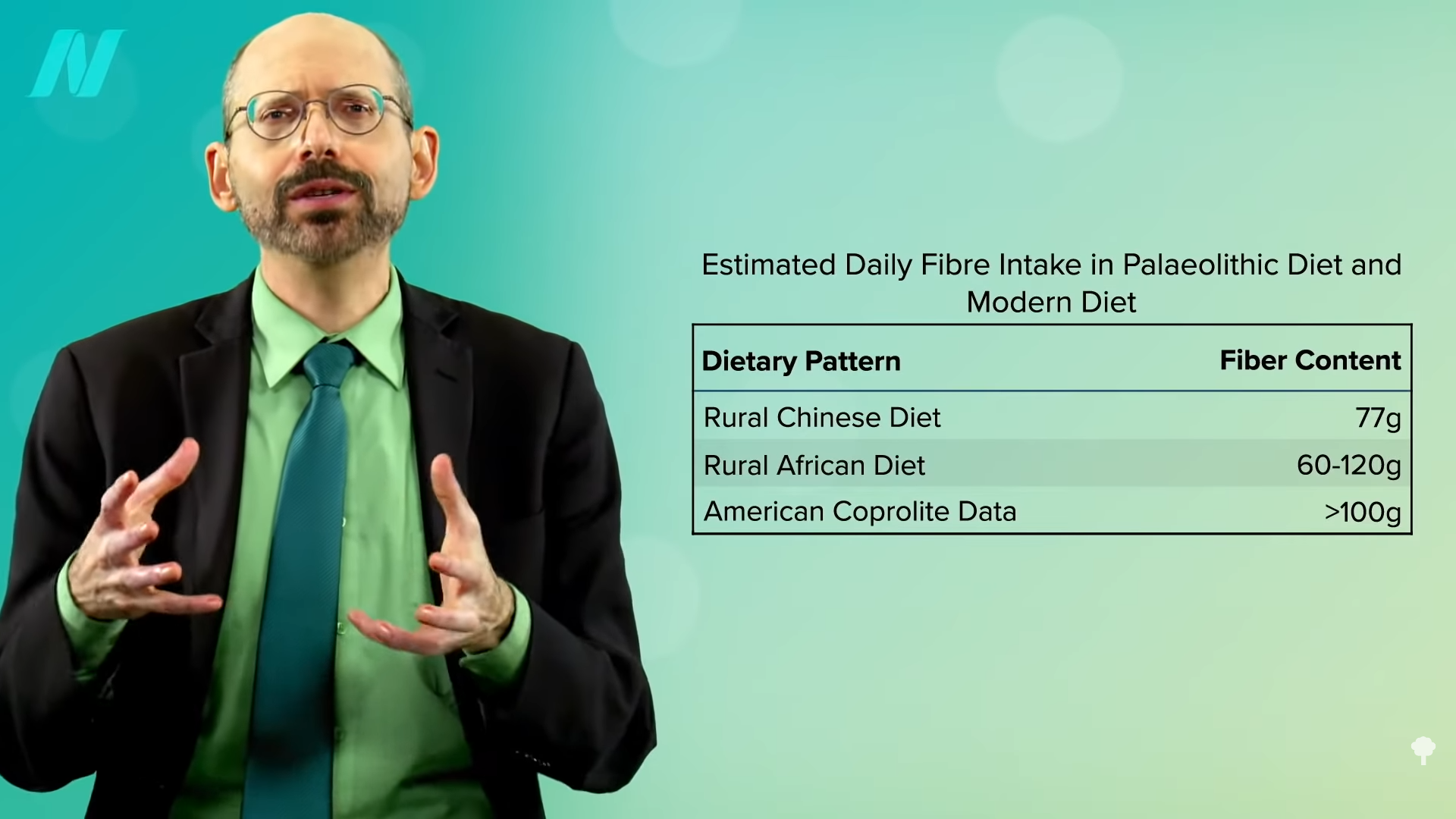

Based on studies of nearly half a million men and women, there doesn’t seem to be any upper threshold of benefit—so, again, “the more, the better.” At more than 25 grams of soluble fiber and 47 grams of insoluble dietary fiber, you can start seeing a significant drop in associated stroke risk. So, one could consider these values “as the minimal recommendable daily intake of soluble and insoluble fiber…to prevent stroke at a population level.” That’s what you see in people eating diets centered around minimally processed plant foods. Dean Ornish, M.D., got up around there with his whole food, plant-based diet. It might not be as much as we were designed to eat, based on the analyses of fossilized feces, but that’s about where we might expect significantly lower stroke risk, as shown below and at 3:25 in my video.

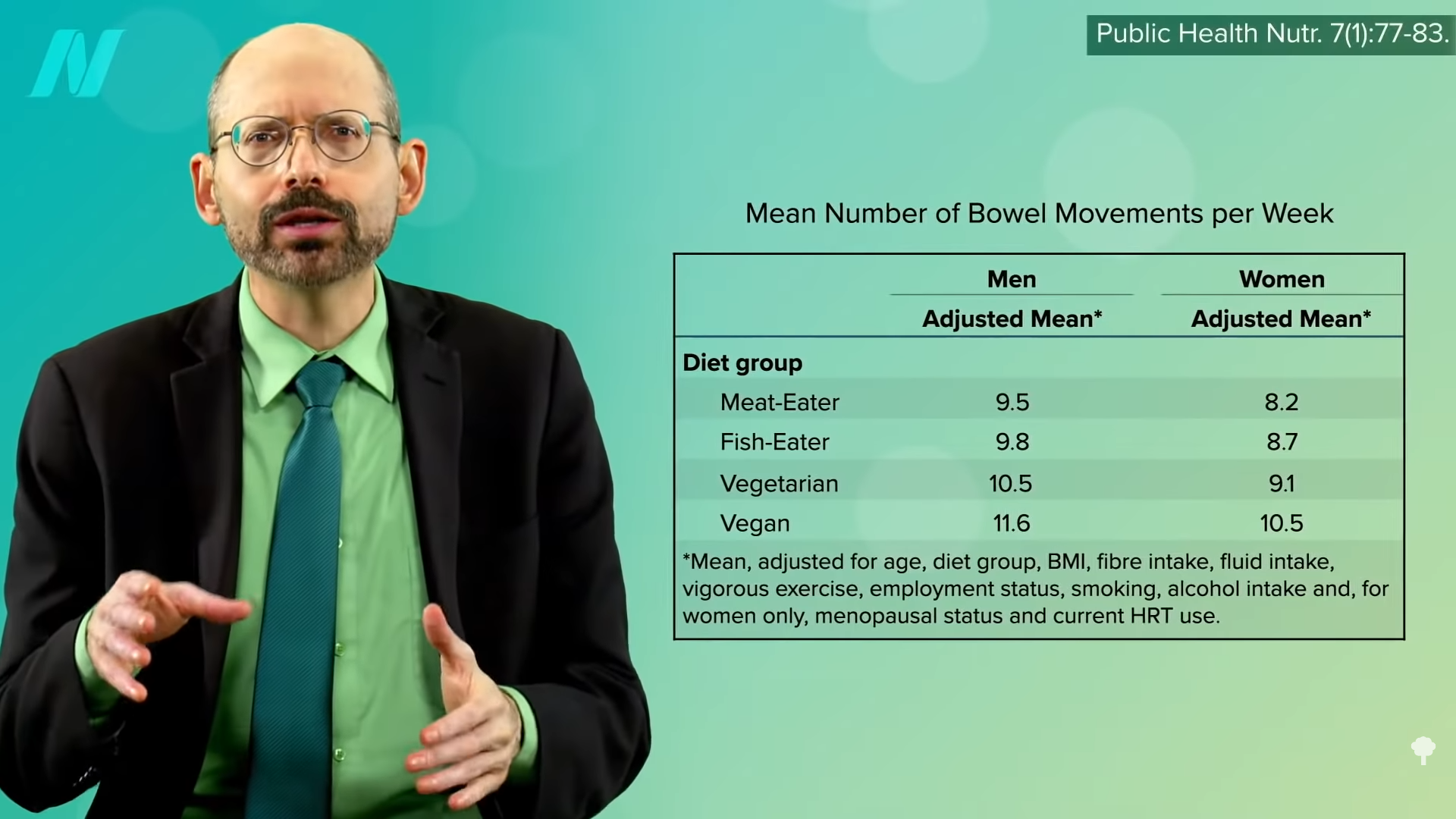

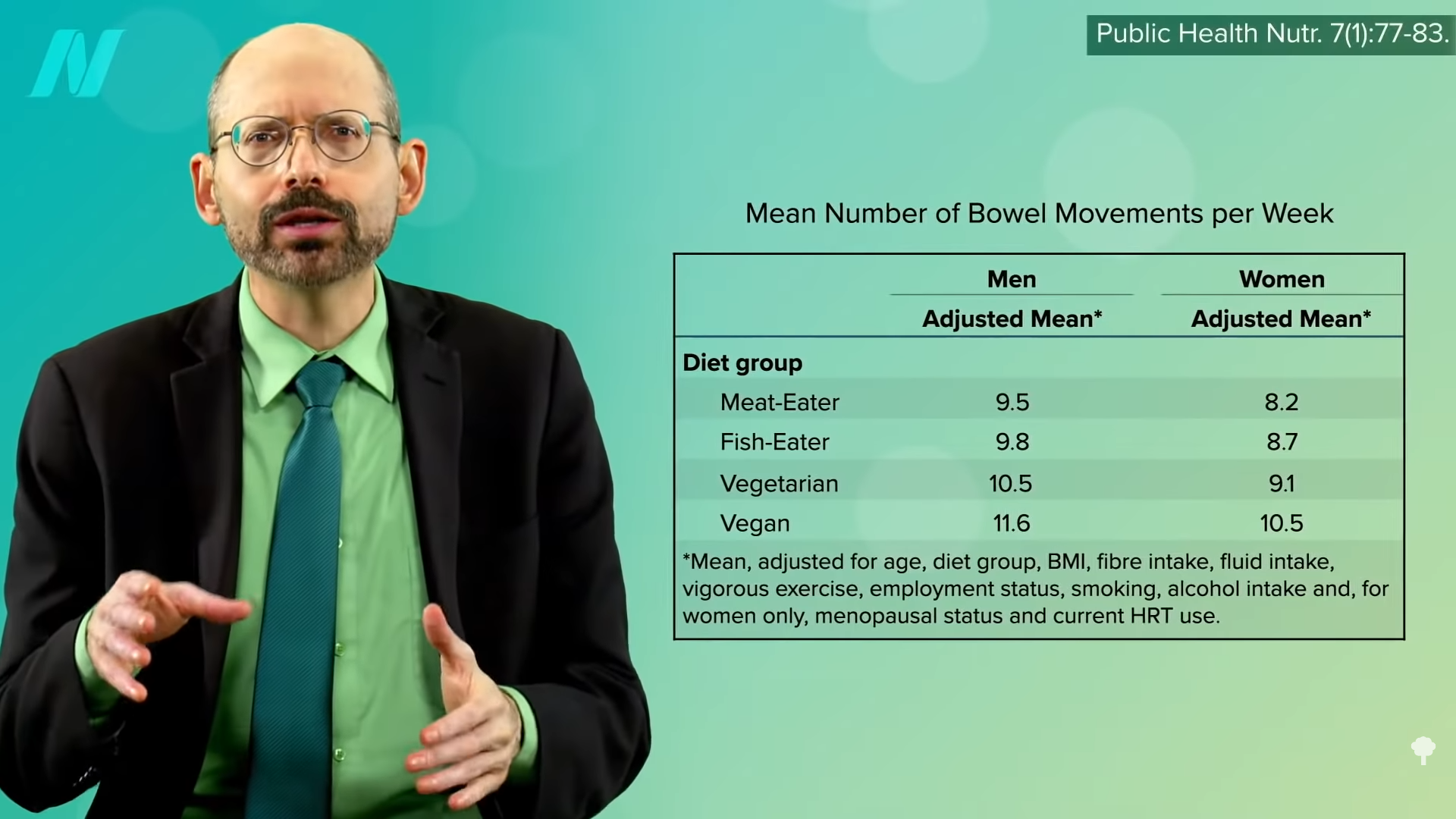

How much were the UK vegetarians getting? 22.1 grams. Now, in the UK, they measure fiber a little differently, so it may be closer to 30 grams, but that’s still not the optimal level for stroke prevention. It’s so little fiber that the vegetarians and vegans only beat out the meat eaters by about one or two bowel movements a week, as you can see below and at 3:48 in my video, suggesting the non-meat eaters were eating lots of processed foods.

The vegetarians were only eating about half a serving more of fruits and vegetables. Intake is thought to reduce stroke risk in part because of their potassium content, but the UK vegetarians at higher stroke risk were eating so few greens and beans that they couldn’t even match the meat eaters. The vegetarians (and the meat eaters) weren’t even reaching the recommended minimum daily potassium intake of 4,700 mg a day.

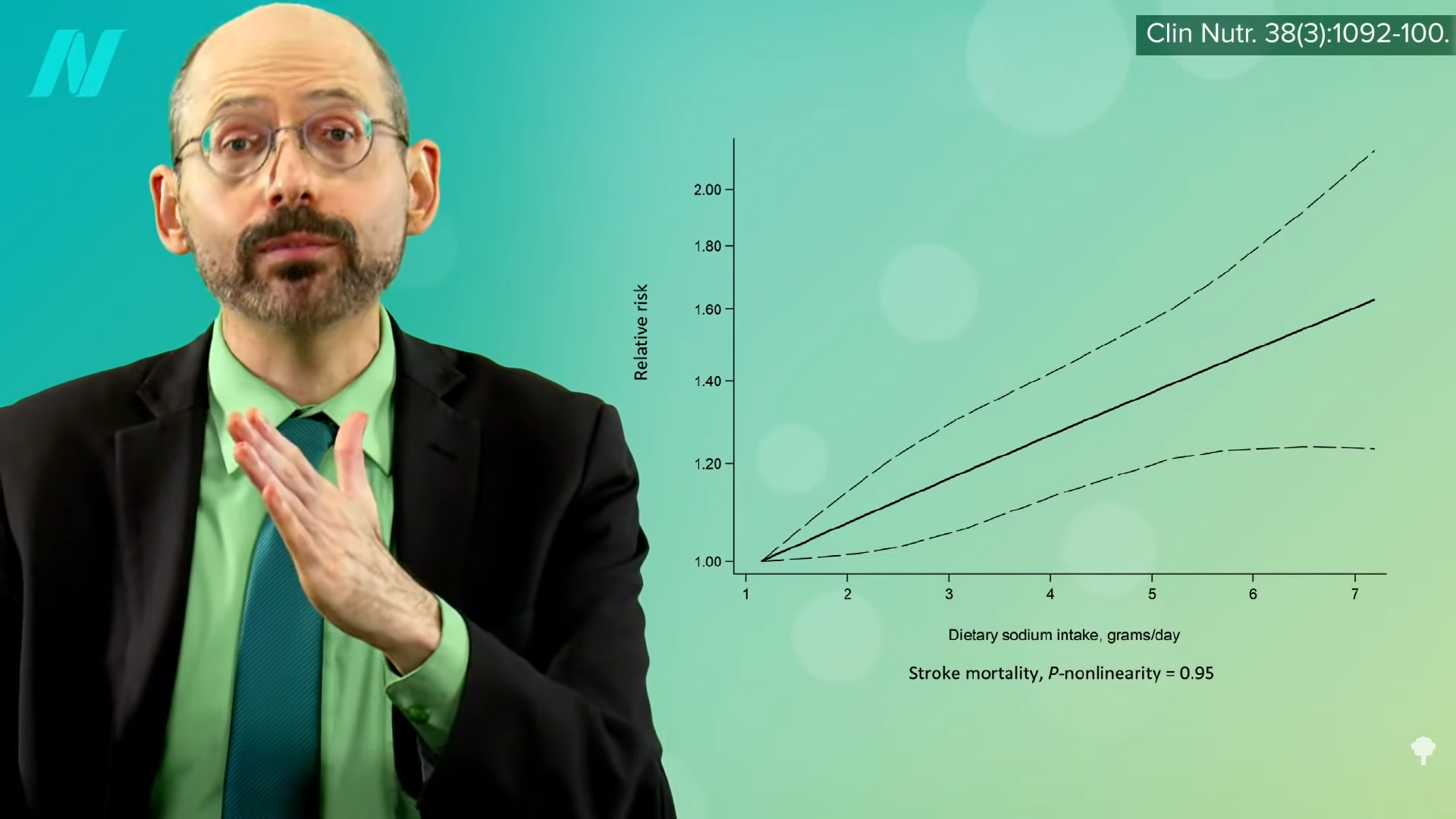

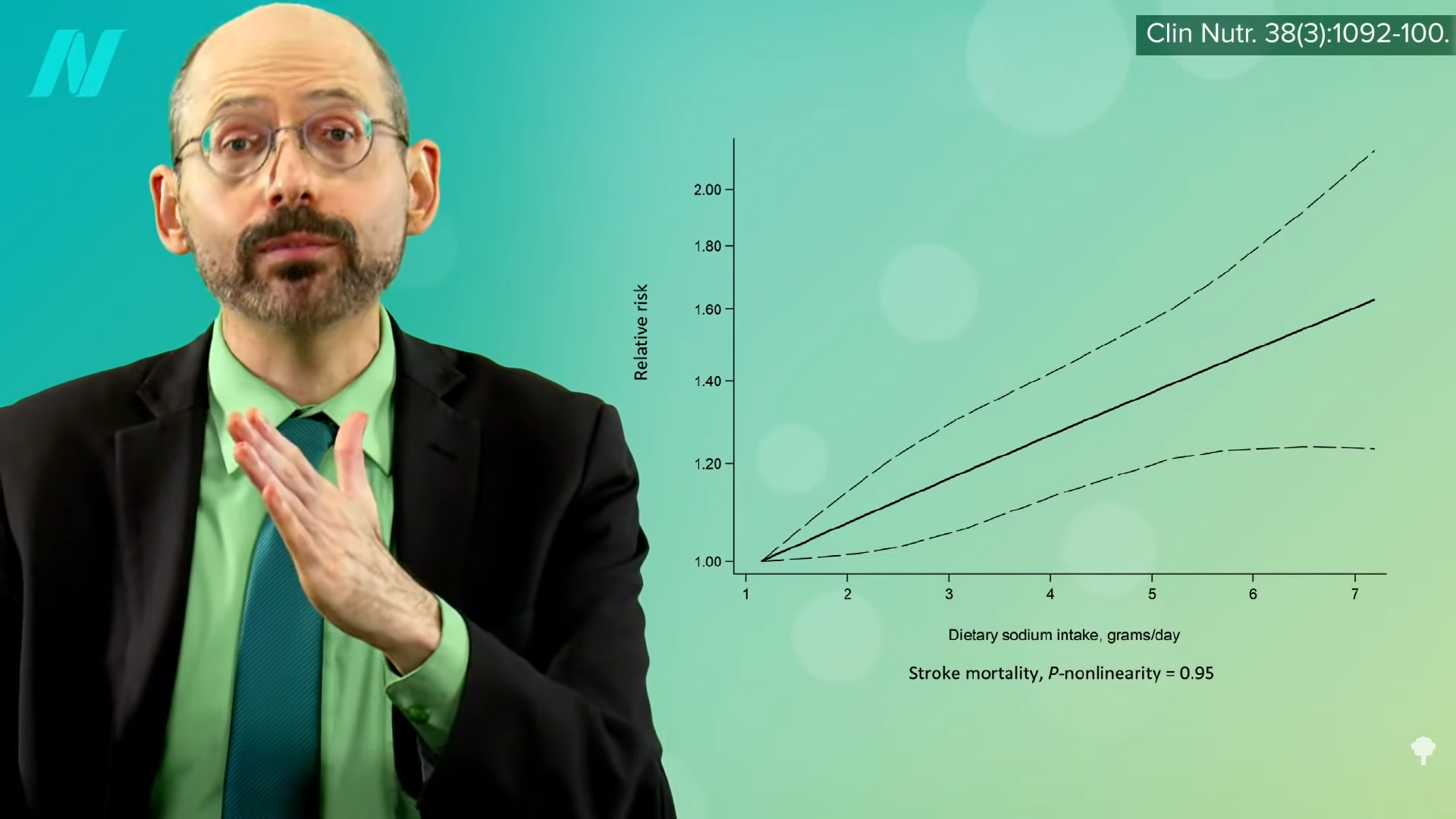

What about sodium? “The vast majority of the available evidence indicates that elevated salt intake is associated with higher stroke risk…” There is practically a straight-line increase in the risk of dying from a stroke, the more salt you eat, as you can see in the graph below and at 4:29 in my video.

Even just lowering sodium intake by a tiny fraction every year could prevent tens of thousands of fatal strokes. “Reducing Sodium Intake to Prevent Stroke: Time for Action, Not Hesitation” was the title of the paper, but the UK vegetarians and vegans appeared to be hesitating, as did the other dietary groups. “All groups exceeded the advised less than 2400 mg daily sodium intake”—and that didn’t even account for salt added to the table! The American Heart Association recommends less than 1,500 mg a day. So, they were all eating a lot of processed foods. It’s no wonder the vegetarians’ blood pressures were only one or two points lower. High blood pressure is perhaps “the single most important potentially modifiable risk factor for stroke.”

What evidence do I have that the vegetarians’ and vegans’ stroke risk would go down if they ate more healthfully? Well, in rural Africa, where they were able to nail the fiber intake that our bodies were designed to get by eating so many whole, healthy plant foods—including fruits, vegetables, grains, greens, beans, and protein almost entirely from plant sources—not only was heart disease, our number one killer, “almost non-existent,” but so was stroke. It only surged up from nowhere “with the introduction of salt and refined foods” to their diet.

“It is notable that stroke and senile dementia appear to be virtually absent in Kitava, an Oceanic culture [near Australia] whose quasi-vegan traditional diet is very low in salt and very rich in potassium.” They ate fish a few times a week, but the other 95 percent or so of their diet was made up of vegetables, fruits, corn, and beans. They had an apparent absence of stroke, even despite their ridiculously high rates of smoking, 76 percent of men and 80 percent of women. We evolved by eating as little as less than an eighth of a teaspoon of salt a day, and our daily potassium consumption is thought to have been as high as 10,000 mg or so. We went from an unsalted, whole-food diet to eating salty, processed foods depleted of potassium whether we eat meat or not.

Caldwell Esselstyn at the Cleveland Clinic tried putting about 200 patients with established cardiovascular disease on a whole food, plant-based diet. Of the 177 who stuck with the diet, only a single patient went on to have a stroke in the subsequent few years, compared to a hundred-fold greater rate of adverse events, including multiple strokes and deaths in those who strayed from the diet. “This is not vegetarianism,” Esselstyn explains. Vegetarians can eat a lot of less-than-ideal foods, “such as milk, cream, butter, cheese, ice cream, and eggs. This new paradigm is exclusively plant-based nutrition.”

This entire train of thought—that the reason typical vegetarians don’t have better stroke statistics is because they’re not eating particularly stellar diets—may explain why they don’t have significantly lower stroke rates. However, it still doesn’t explain why they may have higher stroke rates. Even if they’re eating similarly crappy, salty, processed diets, at least they aren’t eating meat, which we know increases stroke risk. There must be something about vegetarian diets that so increases stroke risk that it offsets their inherent advantages. We’ll continue our hunt for the answer next.

From a medical standpoint, labels like vegan and vegetarian just tell me what you don’t eat. It’s like identifying yourself as a “No-Twinkie-tarian.” You don’t eat Twinkies? Great, but what’s the rest of your diet like?

What are the healthiest foods? Check out my Daily Dozen.

To catch up on the rest of this series, see related posts below.

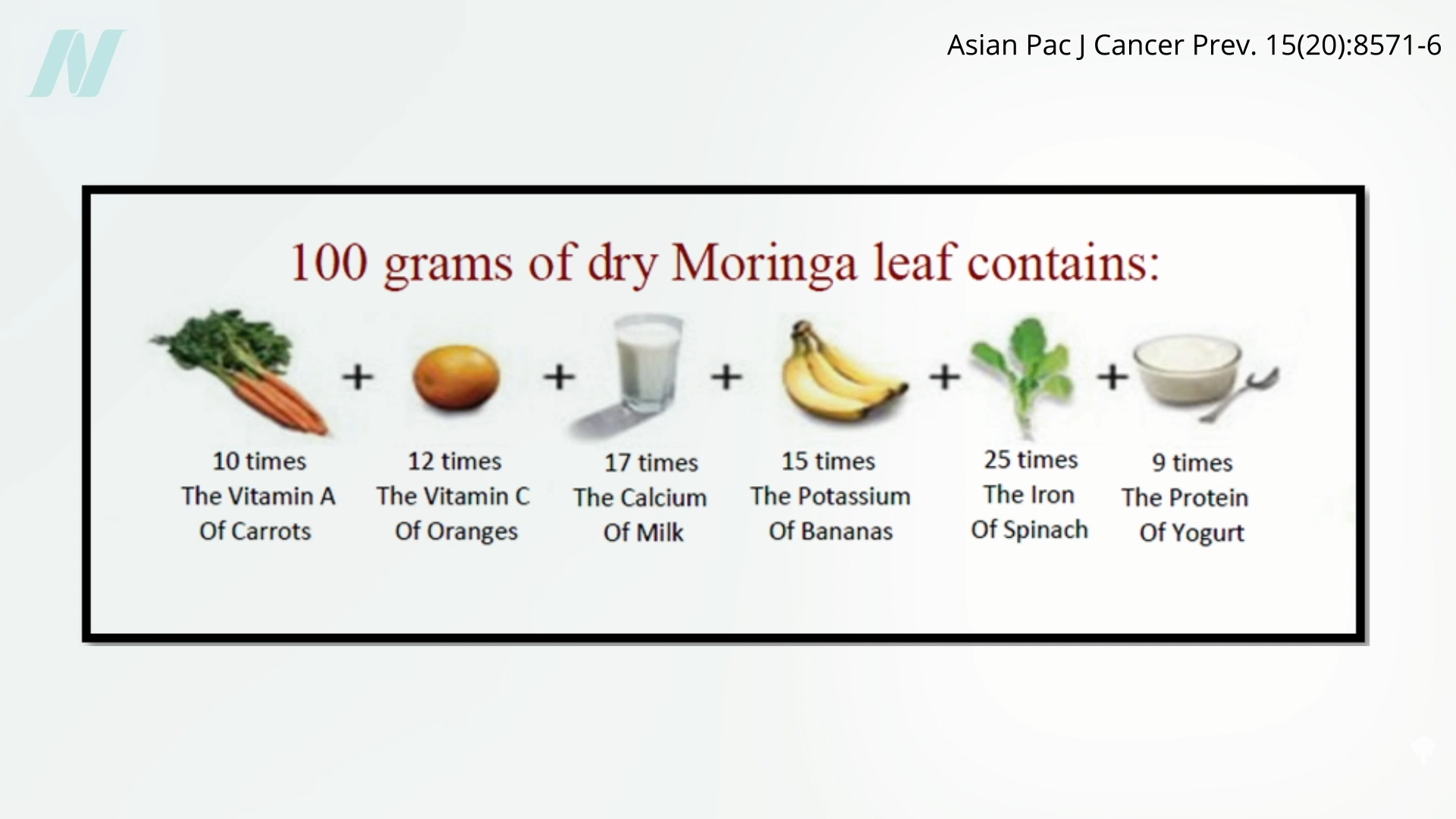

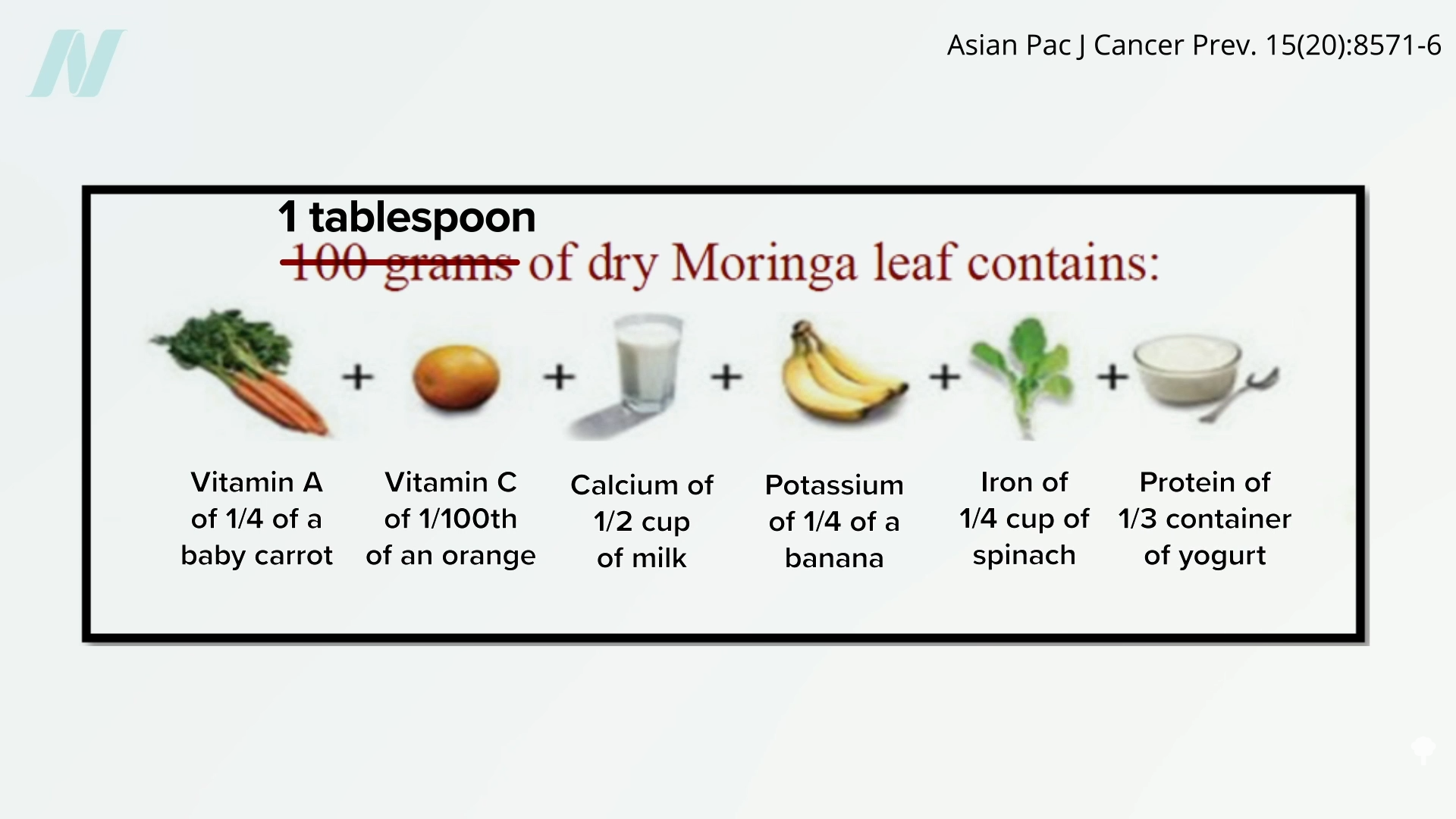

Sounds impressive, but first of all, even if this were true, it is relevant for 100 grams of dry moringa leaf, which is about 14 tablespoons, almost a whole cup of leaf powder. Researchers have had trouble getting people to eat even 20 grams, so anything more would likely “result in excessively unpleasant taste, due to the bitterness of the leaves.”

Sounds impressive, but first of all, even if this were true, it is relevant for 100 grams of dry moringa leaf, which is about 14 tablespoons, almost a whole cup of leaf powder. Researchers have had trouble getting people to eat even 20 grams, so anything more would likely “result in excessively unpleasant taste, due to the bitterness of the leaves.” Moringa does seem to have anticancer activity—in a petri dish—against cell lines of breast cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, and fibrosarcoma, while tending to leave normal cells relatively alone, but there haven’t been any clinical studies. What’s the point in finding out that “Moringa oleifera extract enhances sexual performance in stressed rats,” as one study was titled?

Moringa does seem to have anticancer activity—in a petri dish—against cell lines of breast cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, and fibrosarcoma, while tending to leave normal cells relatively alone, but there haven’t been any clinical studies. What’s the point in finding out that “Moringa oleifera extract enhances sexual performance in stressed rats,” as one study was titled?

Medically-supervised fasting has

Medically-supervised fasting has “

“