Last month, at a dining table in a sunny New York City hotel suite, I found myself thrown completely off guard by a strip of fake bacon. I was there to taste a new kind of plant-based meat, which, like most Americans, I’ve tried before but never truly craved in the way that I’ve craved real meat. But even before I tried the bacon, or even saw it, I could tell it was different. The aroma of salt, smoke, and sizzling fat rising from the nearby kitchen seemed unmistakably real. The crispy bacon strips looked the part too—tiger-striped with golden fat and presented on a miniature BLT. Then crunch gave way to satisfying chew, followed by a burst of hickory and the incomparable juiciness of animal fat.

I knew it wasn’t real bacon, but for a moment, it fooled me. The bacon was indeed made from plants, just like the burger patties you can buy from companies such as Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat. But it had been mixed with real pork fat. Well, kind of. What marbled the meat had not come from a butchered pig but a living hog whose fat cells had been sampled and grown in a vat.

This lab-grown fat, or “cultivated fat,” was made by Mission Barns, a San Francisco start-up, with one purpose: to win people over to plant-based meat. And a lot of people need to be won over, it seems. The plant-based-meat industry, which a few years ago seemed destined for mainstream success, is now struggling. Once the novelty of seeing plant protein “bleed” wore off, the high price, middling nutrition, and just-okay flavor of plant-based meat has become harder for consumers to overlook, food analysts told me. In 2021 and 2022, many of the fast-food chains that had once given plant-based meat a national platform—Burger King, Dunkin’, McDonald’s—lost interest in selling it. In the past four months, the two most visible plant-based-meat companies, Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, have each announced layoffs.

Meanwhile, the future of meat alternatives—lab-grown meat that is molecularly identical to the real deal—is at least several years away, lodged between science fiction and reality. But we can’t wait until then to eat less meat; it’s one of the single best things that regular people can do for the climate, and also helps address concerns about animal suffering and health. Lab-grown fat might be the bridge. It is created using the same approach as lab-grown meat, but it’s far simpler to make and can be mixed into existing plant-based foods, Elysabeth Alfano, the CEO of the investment firm VegTech Invest, told me. As such, it’s likely to become commercially available far sooner—maybe even within the next few years. Maybe all it will take to save fake meat is a little animal fat.

Animal fat is culinary magic. It creates the juiciness of a burger, and leaves a buttery coat on the tongue. Its absence is the reason that chicken breasts taste so bland. Fat, the chef Samin Nosrat wrote in Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, is “a source of both rich flavor and of a particular desired texture.” The fake meat on the market now is definitely lacking in the flavor and texture departments. Most products approximate meatiness using a concoction of plant oils, flavorings, binders, and salt, which is certainly meatier than the bean burgers that came before it, but is far from perfect: The food blog Serious Eats, for instance, has pointed out off-putting flavor notes, at least prior to cooking, including coconut and cat food. On a molecular level, plant fat is ill-equipped to mimic its animal counterpart. Coconut oil, common in plant-based meat, is solid at room temperature but melts under relatively low heat, so it spills out into the pan while cooking. As a result, the mouthfeel of plant-based meat tends to be more greasy than sumptuous.

Replacing those plant oils with cultivated animal fat, which keeps its structure when heated, would maintain the flavor and juiciness people expect of real meat, Audrey Gyr, the start-up innovation specialist at the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit that advocates for plant-based substitutes, told me. In a sense, the technique of using animal fat to flavor plants is hardly new. Chicken schmaltz has long lent rich nuttiness to potato latkes; rendered guanciale is what gives a classic amatriciana its succulence. Plant-based bacon enhanced with pork fat follows from the same culinary tradition, but it’s very high-tech. Fat cells sampled from a live animal are grown in huge bioreactors and fed with plant-derived sugars, proteins, and other growth components. In time, they multiply to form a mass of fat cells: a soft, pale solid with robust flavor, the same white substance you might see encircling a pork chop or marbling a steak.

Out of the bioreactor, the fat “looks a little bit like margarine,” Ed Steele, a co-founder of the London-based cultivated-fat company Hoxton Farms, told me. It is a complicated process, but far easier than engineering cultivated meat, which involves many cell types that must be coaxed into rigid muscle fibers. Fat involves one type of cell and is most useful as a formless blob. Just as in the human body, all it takes is time, space, and a steady drip of sugars, oils, and other fats, Eitan Fischer, CEO of Mission Barns, told me. The bacon I’d tried at the tasting had been constructed by layering cultivated fat with plant-based protein, curing and smoking the loaf, then slicing it into bacon-like strips. Mixing just 10 percent cultivated fat with plant-based protein by mass, Steele said, can make a product taste and feel like the real thing.

Already, cultivated-fat products are within sight. Mission Barns plans to incorporate its cultivated fat into its own plant-based products; Hoxton Farms hopes to sell its fat directly to existing plant-based-meat manufacturers. Other companies, such as the Belgian start-up Peace of Meat, the Berlin-based Cultimate Foods, and Singapore’s fish-focused ImpacFat, are also working on their own versions of cultivated fat. In theory, the fat can be mixed into virtually any type of plant-based meat—nuggets, sausages, paté. In the U.S., a path to market is already being cleared. Last November, cultivated chicken from the California start-up Upside Foods received FDA clearance; now it’s waiting on additional clearance from the Department of Agriculture. Pending its own regulatory approvals, Mission Barns says it is ready to launch its products in a few supermarkets and restaurants, which also include a convincingly porky plant-based meatball I also tried at the tasting. (Due to the pending approval, I had to sign a liability waiver before digging in.)

I left the tasting with animal fat on my lips and a new conviction in my mind: At the right price, I’d buy this bacon over the regular stuff. Because cultivated fat can be made without harming animals—the fat cells in the bacon I tasted came from a happily free-ranging pig named Dawn, a PR rep for Mission Barns told me—it may appeal to flexitarians like myself who just want to eat less meat.

Although there’s no guarantee it would taste as good at home as it did when prepared by Mission Barns’s private chef, with its realistic texture and flavor, cultivated fat could solve the main issue plaguing plant-based meat: It just doesn’t taste that good. Cultivated fat is “the next step in making environmentally friendly foods more palatable to the average consumer,” Jennifer Bartashus, a packaged-food analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, told me.

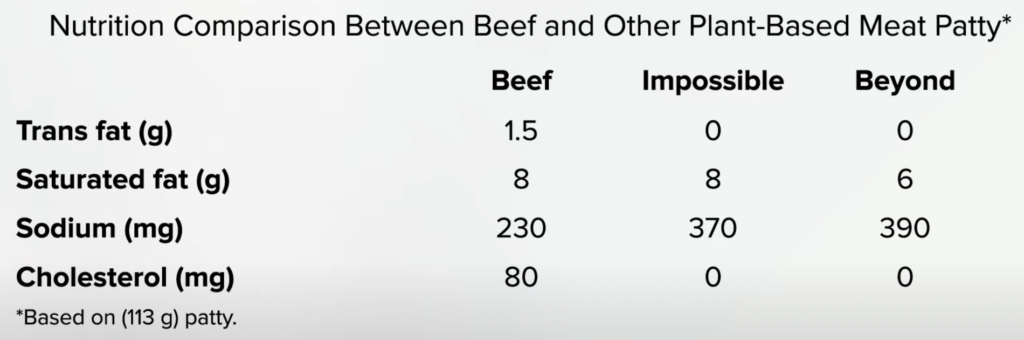

But cultivated fat still faces some of the same problems that have turned America off plant-based meat. The current products for sale are not particularly healthy, and cultivated fat would not change that fact. Building consumer trust and familiarity may also be an issue. Some people are leery of plant-based products because they’re confused about what they’re made of. The more complex notion of cultivated fat may be just as unappetizing, if not more so. “We still don’t know exactly how consumers are going to feel about cultivated fat,” Gyr said. Certainly, finding a catchy name for these products would help, but I have struggled to find a term less clunky than “plant-based meat flavored with cultivated animal fat” to describe what I ate. Unless cultivated-fat companies really nail their marketing, they could go the way of “blended meat”—mixtures of plant-based protein and real meat introduced by three meat companies in 2019, which was “a bit of a marketing failure,” Gyr said.

Above all, though, is the price relative to that of traditional meat. Plant-based meat’s higher cost has partly been blamed for the industry’s slump, and products containing cultivated fat, in all likelihood, will not be cheaper in the near future. Neither founder I spoke with shared specific numbers; Fischer, of Mission Barns, said only that the company’s small production scale makes it “fairly expensive” compared with traditional meat products, while Steele said his hope is that companies using Hoxton Farms’ cultivated fat in their plant-based-meat recipes won’t have to spend more than they do now.

Despite these obstacles, cultivated fat is promising for the flagging plant-based-meat industry because of the fact that it is absolutely delicious. Cultivated fat could “lead to a new round of innovation that will pull consumers back in,” Bartashus said. After all, plant-based and real meat could reach cost parity around 2026, at which point even more companies might want to get in on meat alternatives. Cultivated fat might warm us up to the future of fully cultivated meat. With enough time, lab-grown chicken breasts could become as boring as regular chicken breasts.

Enthusiasm about cultivated fat, and fake meat in general, has a distinctly techno-optimist flavor, as if persuading all meat eaters to embrace plants gussied up in bacon grease will be easy. “Eventually our goal is to outcompete current conventional meat prices, whether it’s meatballs or bacon,” Fischer said. But even as the problems with eating meat have only become clearer, meat consumption in the U.S. has continued to rise. Globally, meat consumption in countries such as India and China is expected to skyrocket in the coming years. At the very least, cultivated fat provides consumers with another option at a time when eating a steak for one meal and then opting for plant-based meat the next can count as a win.

Since the tasting, I’ve often thought about why eating the bacon left me feeling so perplexed. When I gnawed on the crispy golden edge of one of the strips, I knew I was eating real bacon fat, but my brain still wrestled with the idea that it had not come directly from a piece of pork. I’ve only ever known a world where animal fat comes from slaughtered animals. That is changing. If cultivated fat can tide the plant-based-meat industry over until lab-grown meat becomes a reality, these new products will have done their part. In the meantime, we may come to find that they’re already good enough.