CNN

—

Here’s a look at the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in March of 2011.

March 11, 2011 – At 2:46 p.m., a 9.1 magnitude earthquake takes place 231 miles northeast of Tokyo at a depth of 15.2 miles.

The earthquake causes a tsunami with 30-foot waves that damage several nuclear reactors in the area.

It is the largest earthquake ever to hit Japan.

Number of people killed and missing

(Source: Japan’s Fire and Disaster Management Agency)

The combined total of confirmed deaths and missing is more than 22,000 (nearly 20,000 deaths and 2,500 missing). Deaths were caused by the initial earthquake and tsunami and by post-disaster health conditions.

At the time of the earthquake, Japan had 54 nuclear reactors, with two under construction, and 17 power plants, which produced about 30% of Japan’s electricity (IAEA 2011).

Material damage from the earthquake and tsunami is estimated at about 25 trillion yen ($300 billion).

There are six reactors at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi plant, located about 65 km (40 miles) south of Sendai.

A microsievert (mSv) is an internationally recognized unit measuring radiation dosage. People are typically exposed to a total of about 1,000 microsieverts in one year.

The Japanese government estimated that the tsunami swept about five million tons of debris offshore, but that 70% sank, leaving 1.5 million tons floating in the Pacific Ocean. The debris was not considered to be radioactive.

READ MORE: Fukushima: Five years after Japan’s worst nuclear disaster

All times and dates are local Japanese time.

March 11, 2011 – At 2:46 p.m., an 8.9 magnitude earthquake takes place 231 miles northeast of Tokyo. (8.9 = original recorded magnitude; later upgraded to 9.0, then 9.1.)

– The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center issues a tsunami warning for the Pacific Ocean from Japan to the US. About an hour after the quake, waves up to 30 feet high hit the Japanese coast, sweeping away vehicles, causing buildings to collapse, and severing roads and highways.

– The Japanese government declares a state of emergency for the nuclear power plant near Sendai, 180 miles from Tokyo. Sixty to seventy thousand people living nearby are ordered to evacuate to shelters.

March 12, 2011 – Overnight, a 6.2 magnitude aftershock hits the Nagano and Niigata prefectures (USGS).

– At 5:00 a.m., a nuclear emergency is declared at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Officials report the earthquake and tsunami have cut off the plant’s electrical power, and that backup generators have been disabled by the tsunami.

– Another aftershock hits the west coast of Honshu – 6.3 magnitude. (5:56 a.m.)

– The Japanese Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency announces that radiation near the plant’s main gate is more than eight times the normal level.

– Cooling systems at three of the four units at the Fukushima Daini plant fail prompting state of emergency declarations there.

– At least six million homes – 10% of Japan’s households – are without electricity, and a million are without water.

– The US Geological Survey says the quake appears to have moved Honshu, Japan’s main island, by eight feet and has shifted the earth on its axis.

– About 9,500 people – half the town’s population – are reported to be unaccounted for in Minamisanriku on Japan’s Pacific coast.

March 13, 2011 – People living within 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) of the Fukushima Daini and 20 kilometers of the Fukushima Daiichi power plants begin a government-ordered evacuation. The total evacuated so far is about 185,000.

– 50,000 Japan Self-Defense Forces personnel, 190 aircraft and 25 ships are deployed to help with rescue efforts.

– A government official says a partial meltdown may be occurring at the damaged Fukushima Daiichi plant, sparking fears of a widespread release of radioactive material. So far, three units there have experienced major problems in cooling radioactive material.

March 14, 2011 – The US Geological Survey upgrades its measure of the earthquake to magnitude 9.0 from 8.9.

– An explosion at the Daiichi plant No. 3 reactor causes a building’s wall to collapse, injuring six. The 600 residents remaining within 30 kilometers of the plant, despite an earlier evacuation order, have been ordered to stay indoors.

– The No. 2 reactor at the Daiichi plant loses its cooling capabilities. Officials quickly work to pump seawater into the reactor, as they have been doing with two other reactors at the same plant, and the situation is resolved. Workers scramble to cool down fuel rods at two other reactors at the plant – No. 1 and No. 3.

– Rolling blackouts begin in parts of Tokyo and eight prefectures. Downtown Tokyo is not included. Up to 45 million people will be affected in the rolling outages, which are scheduled to last until April.

March 15, 2011 – The third explosion at the Daiichi plant in four days damages the suppression pool of reactor No. 2. Water continues to be injected into “pressure vessels” in order to cool down radioactive material.

March 16, 2011 – The nuclear safety agency investigates the cause of a white cloud of smoke rising above the Fukushima Daiichi plant. Plans are canceled to use helicopters to pour water onto fuel rods that may have burned after a fire there, causing a spike in radiation levels. The plume is later found to have been vapor from a spent-fuel storage pool.

– In a rare address, Emperor Akihito tells the nation to not give up hope, that “we need to understand and help each other.” A televised address by a sitting emperor is an extraordinarily rare event in Japan, usually reserved for times of extreme crisis or war.

– After hydrogen explosions occur in three of the plant’s reactors (1, 2 and 3), Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano says radiation levels “do not pose a direct threat to the human body” between 12 to 18 miles (20 to 30 kilometers) from the plant.

March 17, 2011 – Gregory Jaczko, head of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, tells US Congress that spent fuel rods in the No. 4 reactor have been exposed because there “is no water in the spent fuel pool,” resulting in the emission of “extremely high” levels of radiation.

– Helicopters operated by Japan’s Self-Defense Forces begin dumping tons of seawater from the Pacific Ocean on to the No. 3 reactor to reduce overheating.

– Radiation levels hit 20 millisieverts per hour at an annex building where workers have been trying to re-establish electrical power, “the highest registered (at that building) so far.” (Tokyo Electric Power Co.)

March 18, 2011 – Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency raises the threat level from 4 to 5, putting it on a par with the 1979 Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania. The International Nuclear Events Scale says a Level 5 incident means there is a likelihood of a release of radioactive material, several deaths from radiation and severe damage to the reactor core.

April 12, 2011 – Japan’s nuclear agency raises the Fukushima Daiichi crisis from Level 5 to a Level 7 event, the highest level, signifying a “major accident.” It is now on par with the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the former Soviet Union, which amounts to a “major release of radioactive material with widespread health and environmental effects requiring implementation of planned and extended countermeasures.”

June 6, 2011 – Japan’s Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters reports reactors 1, 2 and 3 at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant experienced a full meltdown.

June 30, 2011 – The Japanese government recommends more evacuations of households 50 to 60 kilometers northwest of the Fukushima Daiichi power plant. The government said higher radiation is monitored sporadically in this area.

July 16, 2011 – Kansai Electric announces a reactor at the Ohi nuclear plant will be shut down due to problems with an emergency cooling system. This leaves only 18 of Japan’s 54 nuclear plants producing electricity.

October 31, 2011 – In response to questions about the safety of decontaminated water, Japanese government official Yasuhiro Sonoda drinks a glass of decontaminated water taken from a puddle at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

November 2, 2011 – Kyushu Electric Power Co. announces it restarted the No. 4 reactor, the first to come back online since the March 11 disaster, at the Genkai nuclear power plant in western Japan.

November 17, 2011 – Japanese authorities announce that they have halted the shipment of rice from some farms northwest of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant after finding higher-than-allowed levels of radioactive cesium.

December 5, 2011 – Tokyo Electric Power Company announces at least 45 metric tons of radioactive water have leaked from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility and may have reached the Pacific Ocean.

December 16, 2011 – Japan’s Prime Minister says a “cold shutdown” has been achieved at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, a symbolic milestone which means the plant’s crippled reactors have stayed at temperatures below the boiling point for some time.

December 26, 2011 – Investigators report poorly trained operators at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant misread a key backup system and waited too long to start pumping water into the units, according to an interim report from the government committee probing the nuclear accident.

February 27, 2012 – Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation, an independent fact-finding committee, releases a report claiming the Japanese government feared the nuclear disaster could lead to an evacuation of Tokyo while at the same time hiding its most alarming assessments of the nuclear disaster from the public as well as the United States.

May 24, 2012 – TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power Co.) estimates about 900,000 terabecquerels of radioactive materials were released between March 12 and March 31 in 2011, more radiation than previously estimated.

June 11, 2012 – At least 1,324 Fukushima residents lodge a criminal complaint with the Fukushima prosecutor’s office, naming Tsunehisa Katsumata, the chairman of Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) and 32 others responsible for causing the nuclear disaster which followed the March 11 earthquake and tsunami and exposing the people of Fukushima to radiation.

June 16, 2012 – Despite public objections, the Japanese government approves restarting two nuclear reactors at the Kansai Electric Power Company in Ohi in Fukui prefecture, the first reactors scheduled to resume since all nuclear reactors were shut down in May 2012.

July 1, 2012 – Kansai Electric Power Co. Ltd. (KEPCO) restarts the Ohi nuclear plant’s No. 3 reactor, resuming nuclear power production in Japan for the first time in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi meltdown following the tsunami.

July 5, 2012 – The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission’s report finds that the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear crisis was a “man-made disaster” which unfolded as a result of collusion between the facility’s operator, regulators and the government. The report also attributes the failings at the plant before and after March 11 specifically to Japanese culture.

July 23, 2012 – A Japanese government report is released criticizing TEPCO. The report says the measures taken by TEPCO to prepare for disasters were “insufficient,” and the response to the crisis “inadequate.”

October 12, 2012 – TEPCO acknowledges in a report it played down safety risks at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant out of fear that additional measures would lead to a plant shutdown and further fuel public anxiety and anti-nuclear movements.

July 2013 – TEPCO admits radioactive groundwater is leaking into the Pacific Ocean from the Fukushima Daiichi site, bypassing an underground barrier built to seal in the water.

August 28, 2013 – Japan’s nuclear watchdog Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) says a toxic water leak at the tsunami-damaged Fukushima Daiichi power plant has been classified as a Level 3 “serious incident” on an eight-point International Nuclear Event Scale (lINES) scale.

September 15, 2013 – Japan’s only operating nuclear reactor is shut down for maintenance. All 50 of the country’s reactors are now offline. The government hasn’t said when or if any of them will come back on.

November 18, 2013 – Tokyo Electric Power Co. says operators of the Fukushima nuclear plant have started removing 1,500 fuel rods from damaged reactor No. 4. It is considered a milestone in the estimated $50 billion cleanup operation.

February 20, 2014 – TEPCO says an estimated 100 metric tons of radioactive water has leaked from a holding tank at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

August 11, 2015 – Kyushu Electric Power Company restarts No. 1 reactor at the Sendai nuclear power plant in Kagoshima prefecture. It is the first nuclear reactor reactivated since the Fukushima disaster.

October 19, 2015 – Japan’s health ministry says a Fukushima worker has been diagnosed with leukemia. It is the first cancer diagnosis linked to the cleanup.

February 29, 2016 – Three former TEPCO executives are indicted on charges of professional negligence related to the disaster at the Fukushiima Daiichi plant.

November 22, 2016 – A 6.9 magnitude earthquake hits the Fukushima and Miyagi prefectures and is considered an aftershock of the 2011 earthquake. Aftershocks can sometimes occur years after the original quake.

February 2, 2017 – TEPCO reports atmospheric readings from inside nuclear reactor plant No. 2. as high as 530 sieverts per hour. This is the highest since the 2011 meltdown.

February 13, 2021 – A 7.1 magnitude earthquake off the east coast of Japan is an aftershock of the 2011 quake, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency.

April 13, 2021 – The Japanese government announces it will start releasing more than 1 million metric tons of treated radioactive water from the destroyed Fukushima nuclear plant into the ocean in two years – a plan that faces opposition at home and has raised “grave concern” in neighboring countries. The whole process is expected to take decades to complete.

September 9, 2021 – The IAEA and Japan agree on a timeline for the multi-year review of Japan’s plan to release treated radioactive water from the destroyed Fukushima nuclear plant into the ocean.

February 18, 2022 – An IAEA task force makes its first visit to Japan for the safety review of its plan to discharge treated radioactive water into the sea.

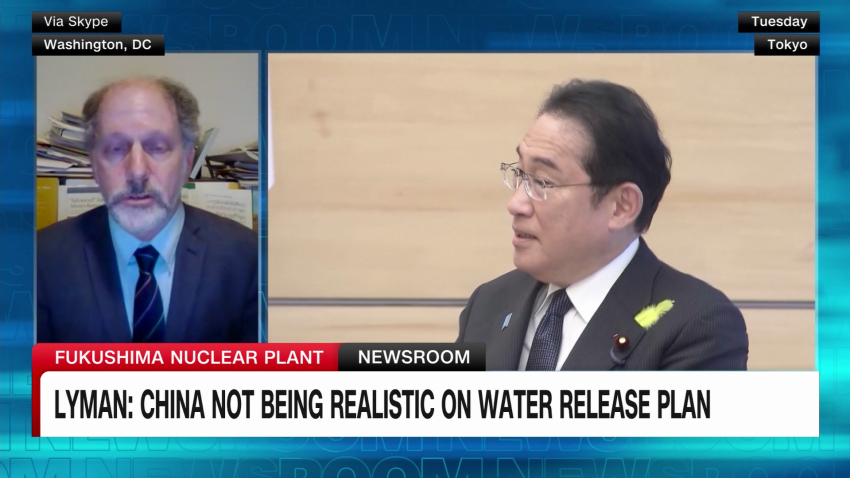

July 4, 2023 – An IAEA safety review concludes that Japan’s plans to release treated radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear plant into the ocean are consistent with IAEA Safety Standards.