click to enlarge

Sam shows a portion of his text with the scammer who bilked him out of more than $500,000

Maybe it was out of boredom, maybe a little bit of hubris and self-gain, or maybe an honest belief that he could score millions of dollars by the end of the week. Whatever the reasoning, Sam pulled the trigger and sent the alluring Asian woman in Los Angeles $3,000 one Monday afternoon last July from the swivel chair in his home office in Solon.

But this wasn’t just any woman on the internet. This was Kristina Tian from Mucker Capital, one of the top venture capital firms in California. Her LinkedIn profile showed she a had finance degree from Stanford and another one from NYU. Everything seemed to check out, with what little checking Sam did. So, when Kristina reached out to the 53-year-old consultant about investing, he listened.

“I work in finance, and have been for a long time,” Kristina explained to Sam on WhatsApp after initially reaching out on LinkedIn. “I have all these excellent products. We multiply money. We do well doing it. We give good returns to people.”

Good returns, Sam thought.

It’s not like he needed them. Since moving to the U.S. in the late nineties, Sam assembled a nice suburban life in Northeast Ohio. He married. He finished his doctorate. He raised his family. He made upper middle class money.

And he invested. He had his reliable sources—an E-Trade account, a Roth IRA, a wallet of crypto coins. Three-thousand dollars wasn’t a big deal to toss into the bucket, even if tied to some random finance director off LinkedIn.

“What kind of returns?” Sam said.

“Good ones. I have been doing this successfully for some time,” Kristina wrote. “I would like to give you a try.”

What do I have to lose, Sam thought.

As instructed, he opened up Coinbase, an app used to buy and manage a variety of cryptocurrencies, and clicked the link Kristina had sent. The portal, “Dexproaeg,” was foreign to him. But there were myriad coins on the market, and anyone could digitally mint the next shining sleeper—Andrew Tate, Iggy Azalea, Donald Trump, the Hawk Tuah Girl. He bought $3,000.

Thirty seconds later, the app surprised Sam. The number clocked up to $8,000.

Wow, this is very good, Sam thought. He looked out at his yard, then back to his phone. His hands shook as he transferred the money to his Chase account. He had stumbled on the world’s greatest secret. How didn’t I know this before?

WhatsApp dinged.

“Oh by the way,” Kristina said, “what kind of car do you drive?”

Sam didn’t really want to say. Nissan. Who cared? It was just a car.

A photo appeared. It was a Bugatti Chiron, a two-door hypercar that retails well over $3 million. It was right there, sitting in Kristina’s garage in Los Angeles. And then, the yacht. The $5 million yacht Kristina was pondering selling after summer ended. Was it real? Kristina’s area code was Los Angeles County—310. She’d sent her location at Sam’s request: the Malibu Country Mart mall off Highway 1. (Where they would meet in-person one day, Kristina said.) But I don’t even boat, Sam thought.

He opened up his Chase account and sent $100,000. He ignored the questionnaire that popped up: “Where are you sending this money?”, “Did anyone tell you to wire this money?”, “Did you meet someone online?”

$185,000, the app read. I can’t believe it.

“Can you talk?” Kristina wrote.

She was calling! Sam was going to talk to Kristina. Should he? What would his wife think? It was just platonic; this was a business relationship. He opened the call. There she was on video, with her parted black hair, red lipstick and eyebrows like half moons.

“Hi,” Sam said.

“Hey, how are you doing?,” Kristina said in a dense Chinese accent, sitting in a plush, white chair in front of a wall of fashion books. “We need to hedge against the risk. Do you know what that means?”

“Yes, I know what that means.”

“We’re doing good,” she said. She sent Sam a screenshot of her app, showing returns totaling $300,000. “You know, we could make a few million per month, provided we have enough capital in the account. You could, if you wanted to, buy a $12 million house in LA. We could make at least $3 million per month—we just need to invest for four, five months.”

Sam laughed. “I’m not in a rush to get a $12 million house,” Sam told her. He wasn’t. Maybe secure his kids’ future. Maybe double his current net worth. Beef up his retirement.

“I just got back from Hawaii. Do you like Hawaii?” Kristina said. “You could make similar trips. You could do anything you’re unable to do in your life.”

“Oh okay,” Sam said.

Sam went to bed four nights in a row mulling over Kristina. It felt like a tryst. No one knew. Not his wife, his daughters, his best friend. Nevertheless, Sam threw over $500,000 into Kristina’s crypto account by the end of that week at the end of July.

That Thursday, Sam woke up in the middle of the night. There was a ding on his phone. He rolled over and saw he’d received an email. It wasn’t from Kristina. Which relieved Sam: she had been texting and calling ad nauseam, urging him to throw yet another $100,000 into the account.

It was an email from an FBI agent in Des Moines, Iowa.

“Dear Sam,” it read. “Based on your recent transactions, we have identified you as a potential victim to a cryptocurrency scam, one that will make you deposit money…” He shut his phone immediately.

The next day, Sam opened up WhatsApp. A reverse image search confirmed that “Kristina Tian”—her LinkedIn profile name—was actually a picture of Chinese influencer Eliana Jing. There was no Kristina Tian.

“Master manipulator,” Sam wrote.

“I feel for you,” Kristina wrote a day later. “You’re a good pig, just not fat enough. But thank you for giving me half of your savings.”

“Wrong,” Sam said. “You were not close enough.”

“Lol, I enjoyed it. And thank you for the money so I can find more.” She sent a crazy eyes emoji. “Glad to use your life savings.”

***

Fattening up a pig, as many farmers know, boils down to two main principles. One, keeping that pig on a consistent stream of hearty foods, of soybeans or barley, maybe vegetable oils or tallow. And second, minimizing stress: keep access to feed easy, space luscious and outside animals away.

This, to keep the metaphor going, is what cryptocurrency scammers have gotten really, really good at doing: casting a dragnet across the world—from the homes of the United Kingdom to Tempe, Arizona—and locating pigs worth fattening up over time, over months or even years. And then, only when they’ve reached the apex of their plumpness, bring those pigs to slaughter.

In the world of internet crimes, this is known as pig butchering, and it is by far the biggest and most worrisome digital crime for authorities in the past decade. Bitcoin’s explosion on the Stock Exchange, dovetailed with years of pandemic boredom, smartphone ubiquity and ease of access to a trove of apps—Crypto.com, Binance, Coinbase—have helped facilitate the most popular and devastating financial crime today with global reach. And its victim count and perpetrator base, from Southeast Asia to Central Ohio, only continues to grow.

The sheer amount of money sent, and lost, in online scams is pretty staggering, according to a 2024 report from the FBI’s Internet Crime Complain Center. Money lost around the globe, whether it be from shady toll scams or from fake lovers, has quadrupled in the past five years, from $4 billion reported lost in 2020 to almost $17 billion last year. And crypto tops every single category, from number of complaints to amount of money lost. (It’s the number one leading digital crime reported in Ohio.) And the complaints just keep on coming. In 2020, crypto-related grifts tallied in the four figures; last year, there were 150,000.

And that’s not even the toughest fact. In your typical wire fraud case, there’s about an 80 percent chance you’ll get your money back if you report it to the Feds within three days. In interviews with three investment scam experts, all told me that the chances of getting your money back after it’s entered the blockchain is less than 10 percent.

“‘Unfortunately, I have some bad news for you.’ That’s usually how I start most of these conversations,” Steven Stransky, a cybersecurity expert at the Thompson Hine law firm, told me. Stransky, who helps the scammed—which include everyone from retired Clevelanders to investment arms of corporations—enter the sluggish legal process of getting money back, said the odds of returning a faux crypto investment is a lot thinner. “I would say that I’ve seen less than one percent of my clients be able to recover lost finances.”

“My experience,” he added, “is that it’s almost never recoverable.”

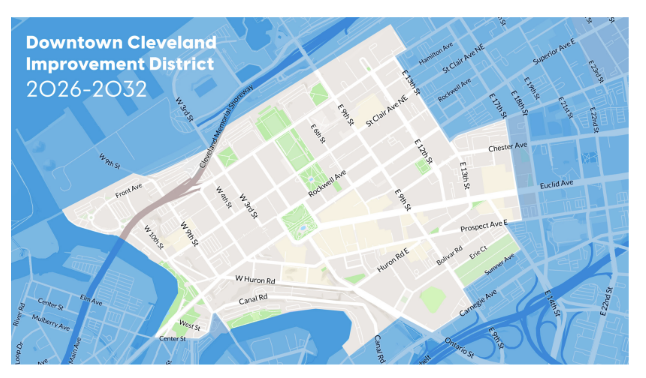

Therein lies the goal of the Midwestern Cryptocurrency Task Force: to fight against that almost never. Here, in a second-story room in the Cleveland FBI office off Lakeside Avenue, is the hardest-working group of agents between New York and Chicago in the world of crypto crimes.

click to enlarge

Mark Oprea

Agent Milan Kosanovich at his office

Started by Special Agent Milan Kosanovich in 2018 to combat the astonishing influx of reports to the IC3, the MCTF comprises about a dozen financial crime experts across Northern Ohio and acts as an investigative link between two of the FBI’s largest crypto-tailored operations in its history—Operation Level Up and Operation Golden Sweep, the latter Kosanovich kicked off in 2023. The goal: perfect the job of tracing digital breadcrumbs along the blockchain, the global ledger of coin trading, from the scam center in China or Myanmar to, say, Sam in Solon’s wallet. And try and get the money back.

“The problem is this: everything in the blockchain— Bitcoin, Ethereum, TRON—once you send it, you can’t undo it,” Kosanovich told me. “It’s gone. Type in the wrong address? It’s gone. You can’t call Mr. Bitcoin or Mrs. Bitcoin, and say, ‘Hey, can you undo that transaction?’”

About a year after he first made contact with Sam, Kosanovich invited me to watch him work, in the command center of the MCTF, in July. He keeps cleanly-cut, salt-and-pepper hair, and wears a flag pin on the chest of a black-and-white suit straight out of Men in Black. A former hostage negotiator, Kosanovich has lectured on finance crimes in 11 countries, is a member of the FBI’s Cyber Criminal Squad and was once a supervisor for the bureau’s Economic Crimes Unit in Washington, D.C. He keeps a glass-is-half-full demeanor in, it seems, every realm of his life. “I’m of the opinion that anything’s better than nothing.”

At a desk holding a wall of computer monitors, Kosanovich brought up a simulation of a typical exchange on the blockchain. In a diagram that resembled a series of jellyfish tied together, sixty-year-old “Jonathan” from Utah sent money to a wallet with a specific code. The transfer’s public, so Kosanovich traces the transaction as far through the blockchain as he can go. This is essentially a game of hot potato. If, say, the transfer’s been identified trickling to and from a series of wallets on Kraken or Tether, then Kosanovich records that information from the ledger to build a case.

But trying to find the money is like trying to nab a package without knowing what the delivery truck looks like. And scammers know this. Money deposited in their wallets is almost immediately lifted, usually in just an hour, to another wallet. And then another. Then, finally, with the help of hired mules, into a bank account tied to the operators themselves. Which is the gold of Golden Sweep: pinpointing exactly where money has been and will soon go. And do that in minutes.

“I spend a lot of time going to other people’s desks. ‘Have you seen this before? Have you seen that?’” Kosanovich told me. He traced his cursor through the hoops and lines of the blockchain diagram. It stopped at the final wallet address, a lengthy line of characters, one still in the pocket of the crypto service, Tether. Kosanovich was so attuned to what he was doing that he barely flinched at the shouts from the hostage negotiation training going on next door.

Kosanovich stood up and pointed to the wallet. “If it gets here? We can freeze that money,” he said. “And if we can’t? It’s gone. That is the dance and the challenge of this work.”

***

Her name, the presentation file said, is Jessica. She’s 33 years old, five-and-a-half feet tall, weighs just over 110 pounds. She’s a Leo—“a spirited fire sign”—and was the child of a binational marriage, an American father and Belarusian mother. She’s “pleasing,” “attractive” and “elegant.”

Jessica is also a go-getting entrepreneur, a college graduate aspiring to resurrect her dream of opening a clothing studio. But three years in she has hit a roadblock. She wants to “scale up” her business with top-shelf designs, and doing so requires a heap of money she doesn’t have access to by normal means. “Faced with this problem,” Jessica said, “I’m stuck with funding.” Jessica, as would have it, is direly looking to invest in some cryptocurrency.

But Jessica, you must know, is not real. She is a character created by supervisors at a massive scam compound called KK Park, an enclosed village with offices and hotels on the border of Myanmar and western Thailand. There, hundreds of trafficked workers—mostly bilingual Chinese jobseekers tricked by bait-and-switch ads—are forced to message hundreds, if not thousands, of people a day. If they don’t, they’re laid in between rows of computers and punched or smacked with metal pipes; others are tied in crucifixion poses or electrocuted. But they are all, involuntarily and opportunistically, Jessica.

Against the backdrop of Myanmar’s civil war, which has been pummeling the country’s economy since May 2021, a wave of rebel groups has since then capitalized on the country’s areas with lax or unenforced laws. And in the past four years, Southeast Asia has exploded with compounds like KK Park: one 2023 report from the UN counted 17 of them, from the northern tip of Myanmar to the southern border of Cambodia. That’s over 220,000 scammers, the report found, that operate in the hierarchical fashion of, say, a midsized tech company. Well, with a culture closer to a prison. “You have everything you need,” one expert put it. “Because once you enter, you can’t leave.”

It was highly likely—Kosanovich suggested 99 percent likely—that Kristina Tian, the supposed investor that grifted Sam in Solon, was a character created by one of these compounds. A reality hard to swallow for people like Sam and the FBI. The vast majority of those on the other end of those strange texts (“Hey how are you?”, “When are we meeting for dinner tonight?”), LinkedIn DMs, or shady Tinder profiles are trafficked victims of scams themselves.

Which begs the question: How does a government agency 8,500 miles away from Mae Sot, Thailand, catch and prosecute people who have scammed hundreds, if not thousands, of Americans out of billions of dollars?

“The ultimate goal is not the person on the phone; it’s the person directing the person on the phone,” Kosanovich told me. “They’re the one orchestrating all of this. That’s why we want to give people their money back: we don’t want those funds to go to the back end.”

A lot of the work on the ground lies in links between anti-scam organizations and Southeast Asian militaries. In February, China, Myanmar and Thailand backed rescue raids of scam compounds, including KK Park. Over 7,000 trafficked victims were rescued and set up for repatriation come March. Electricity was shut off to others. “But that has not stopped anything,” one worker for the International Justice Mission said. “Not even for one day.”

While reporting this story, in the beginning of July, I, like countless others, got yet another scam text. It’s from Joanna. A Joanna from LinkedIn’s HR team who wants to know if I’m up for a new job. I say yes and soon I’m talking to Mireille on WhatsApp. She wants a screenshot of the text from Joanna. I say no. I say, “This just seems weird to me. Can’t we just talk about the job?”

“Due to limited availability,” Mireille writes, “we need to see the text message in order to receive the training.”

“I’m so confused!” I write. “Is this a real job or not?”

“I need to see the time of the text message,” she said. “Of course it’s true.” Joanna is the recruiter, she said, and she is a “staff member for this company.”

At that, my attempt to be annoying simmers into a cold guilt: What if my tomfoolery leads to this person, this Mireille, into a day’s worth of flogging?

I open up Google Translate, then send the following in Chinese, for which I never get a reply: “Where are you?” I text. “Are you okay?”

***

At the end of last year, a few months after the FBI reached out to him, Sam found out that he was one of the luckiest of victims. Recent operations helped freeze and seize $8.2 million from Tether, including $1.1 million tied to four local victims, Sam and his $507,562 being one of them.

They are all waiting to get their money back from the U.S. government through the forfeiture process, DOJ attorney James Morford told me.

These are bizarre cases. They’re not against the scammers. The money itself, Morford said, is the defendant. Sam must prove the $500,000 was really his money as it entered and then went through Coinbase. “Simply stated,” Morford said, Sam “must demonstrate that he obtained the funds legitimately.”

Assuming it goes smoothly, Sam will have his money back by the beginning of 2027.

A startling fact considering that no one in his life knows he lost a half million to a crypto scam. “My wife doesn’t know. My kids don’t know,” Sam reminded me recently over coffee. Sam smiles as he talks—and he talks a lot—as if he was chitchatting about a botched bet on a baseball game, not the equivalent of someone’s life savings. “I’ll put it this way. I have a best friend. We’ve been friends for 25 years now. We share everything. About our families. Work.” Sam sipped his coffee, and said, “But I would never, never tell him about this.”

Halfway through our meeting, Sam took out his phone to answer a text. It’s a message on WhatsApp, he showed me, from a Jessica. “I do this every day,” he said, scrolling through a conversation about cooking tips. There are dozens of chats with Asian women with American names. “I’m not kidding. Every day there is someone new. Whoever reaches out to me, I just keep them engaged. And once the engagement does end, I tell them exactly who they are and their intentions.”

“What do you say?”

Sam laughed and scrolled to a recent comment. It was to Jessica.

“Yeah you are looking for a fat pig to butcher, aren’t you?” Sam had written.

“And then you block them,” I said.

“Yes, and then I block them.”

And that $500,000? What will Sam do with it once the check clears in a year and a half? I expected a reverie about retirement. Instead, he smiled monkishly. He looked around at the other café goers, then back to me.

“That’s the thing about money,” he said. “It will deteriorate your health. Your well-being. Your thinking. Your demeanor. And it’s not like the entire world is bad, right? It’s not like everybody is bad, right?”

“But I guess that’s my one piece of advice,” Sam said. “Don’t trust somebody if they just randomly bumped into you.”

Subscribe to Cleveland Scene newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed