Having a “normal” cholesterol level in a society where it’s normal to die from a heart attack isn’t necessarily a good thing.

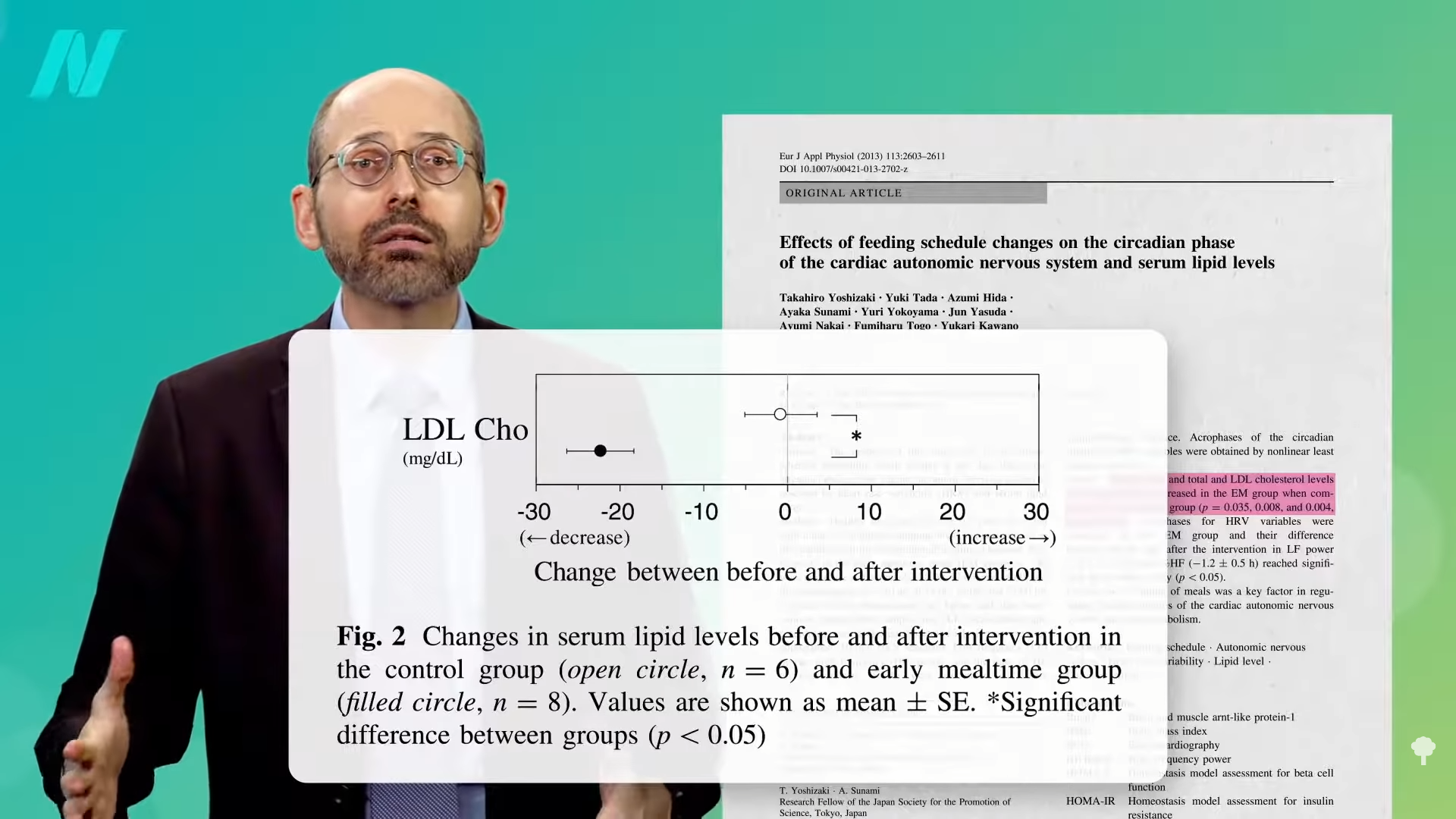

“Consistent evidence” from a variety of sources “unequivocally establishes” that so-called bad LDL cholesterol causes atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease—strokes and heart attacks, our leading cause of death. This evidence base includes hundreds of studies involving millions of people. “Cholesterol is the cause of atherosclerosis,” the hardening of the arteries, and “the message is loud and clear.” “It’s the Cholesterol, Stupid!” noted the editor of the American Journal of Cardiology, William Clifford Roberts, whose CV is more than 100 pages long as he has published about 1,700 articles in peer-reviewed medical literature. Yes, there are at least ten traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, as seen below and at 1:11 in my video How Low Should You Go for Ideal LDL Cholesterol?, but, as Dr. Roberts noted, only one is required for the progression of the disease: elevated cholesterol.

Your doctor may have just told you that your cholesterol is normal, so you’re relieved. Thank goodness! But, having a “normal” cholesterol level in a society where it’s normal to have a fatal heart attack isn’t necessarily good. With heart disease, the number one killer of men and women, we definitely don’t want to have normal cholesterol levels; we want to have optimal levels—and not optimal by current laboratory standards, but optimal for human health.

Normal LDL cholesterol levels are associated with the hidden buildup of atherosclerotic plaques in our arteries, even in those who have so-called “optimal risk factors by current standards”: blood pressure under 120/80, normal blood sugars, and total cholesterol under 200 mg/dL. If you went to your doctor with those kinds of numbers, you’d likely get a gold star and a lollipop. But, if your doctor used ultrasound and CT scans to actually peek inside your body, atherosclerotic plaques would be detected in about 38% of individuals with those kinds of “optimal” numbers.

Maybe we should define an LDL cholesterol level as optimal only when it no longer causes disease. What a concept! When more than a thousand men and women in their 40s were scanned, having an LDL level under 130 mg/dL left them with atherosclerosis throughout their body, and that’s a cholesterol level at which most lab tests would consider normal.

In fact, atherosclerotic plaques were not found with LDL levels down around 50 or 60, which just so happens to be the levels most people had “before the introduction of western lifestyles.” Indeed, before we started eating a typical American diet, “the majority of the adult population of the world had LDLs of around 50 mg per deciliter (mg/dL)”—so that’s the true normal. “Present average values…should not be regarded as ‘normal.’” We don’t want to have a normal cholesterol based on a sick society; we want a cholesterol that is normal for the human species, which may be down around 30 to 70 mg/dL or 0.8 to 1.8 mmol/L.

“Although an LDL level of 50 to 70 mg/dl seems excessively low by modern American standards, it is precisely the normal range for individuals living the lifestyle and eating the diet for which we are genetically adapted.” Over millions of years, “through the evolution of the ancestors of man,” we’ve consumed a diet centered around whole plant foods. No wonder we have a killer epidemic of atherosclerosis, given the LDL level “we were ‘genetically designed for’ is less than half of what is presently considered ‘normal.’”

In medicine, “there is an inappropriate tendency to accept small changes in reversible risk factors,” but “the goal is not to decrease risk but to prevent atherosclerotic plaques!” So, how low should you go? “In light of the latest evidence from trials exploring the benefits and risks of profound LDLc lowering, the answer to the question ‘How low do you go?’ is, arguably, a straightforward ‘As low as you can!’” “‘Lower’ may indeed be better,” but if you’re going to do it with drugs, then you have to balance that with the risk of the drug’s side effects.

Why don’t we just drug everyone with statins, by putting them in the water supply, for instance? Although it would be great if everyone’s cholesterol were lower, there are the countervailing risks of the drugs. So, doctors aim to use statin drugs at the highest dose possible, achieving the largest LDL cholesterol reduction possible without increasing risk of the muscle damage the drugs may cause. But when you’re using lifestyle changes to bring down your cholesterol, all you get are the benefits.

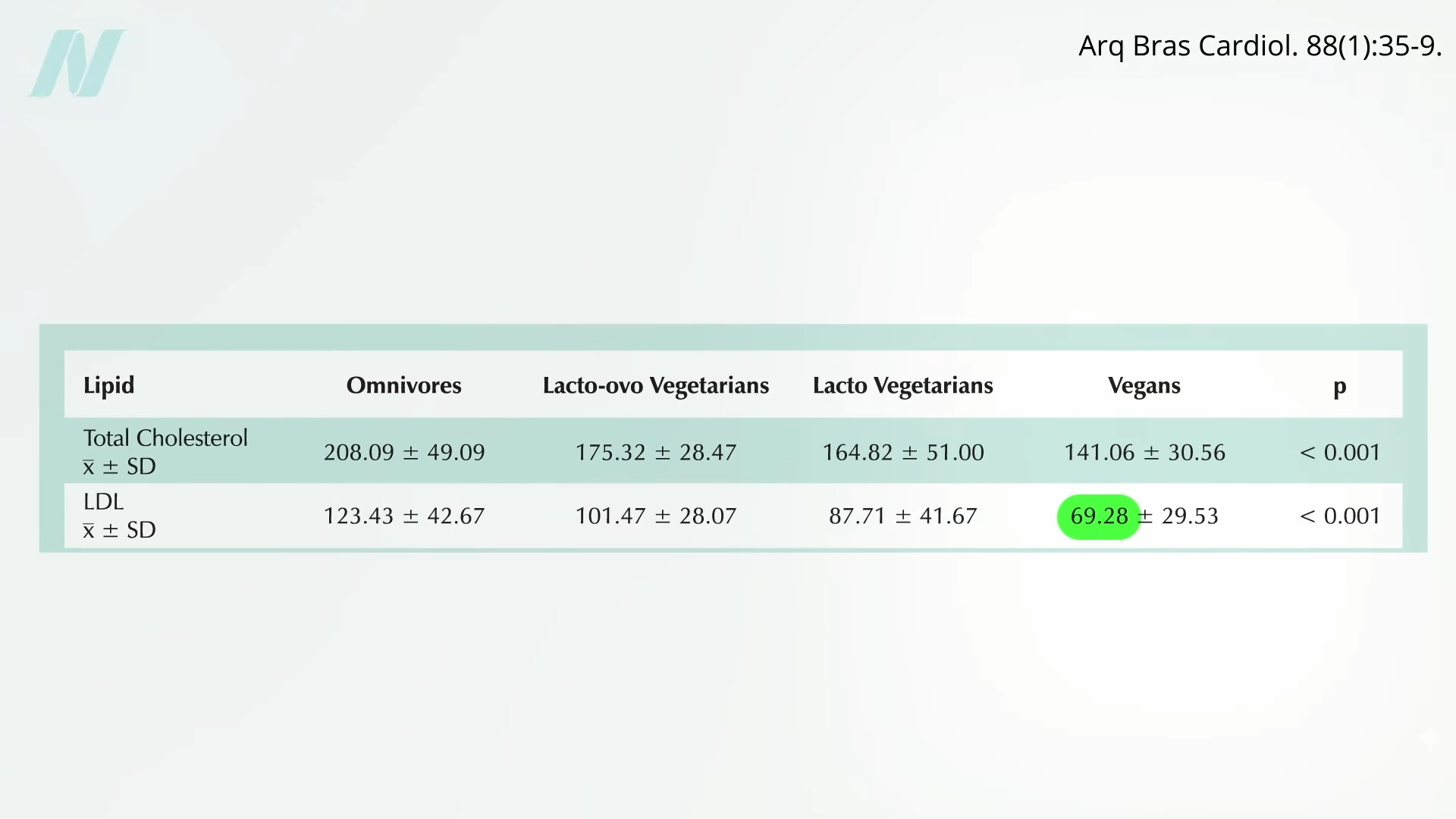

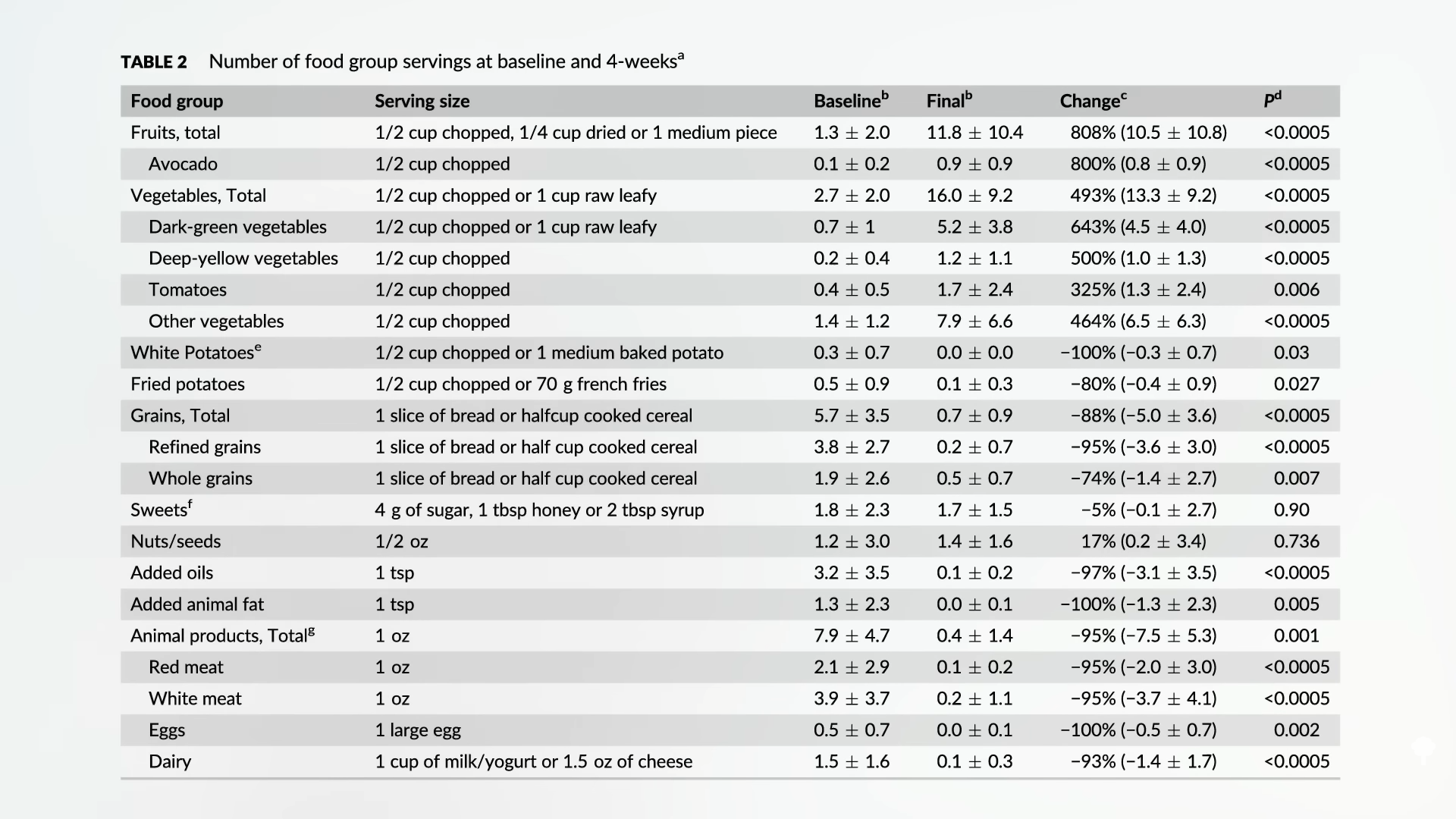

Can we get our LDL low enough with diet alone? Ask some of the country’s top cholesterol experts what they shoot for, “and the odds are good that many will say 70 or so.” So, yes, we should try to avoid the saturated fats and trans fats found in junk foods and meat, and the dietary cholesterol found mostly in eggs, but “it is unlikely anyone can achieve an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL with a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet alone.” Really? Many doctors have this mistaken impression. An LDL of 70 isn’t only possible on a healthy enough diet, but it may be normal. Those eating strictly plant-based diets can average an LDL that low, as you can see here and at 5:28 in my video.

No wonder plant-based diets are the only dietary patterns ever proven to reverse coronary heart disease in a majority of patients. And their side effects? You get to feel better, too! Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that more plant-based dietary patterns significantly improve psychological well-being and quality of life, with improvements in depression, anxiety, emotional well-being, physical well-being, and general health.

For more on cholesterol, see the related posts below.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link