The first study in history on the incidence of stroke in vegetarians and vegans suggests they may be at higher risk.

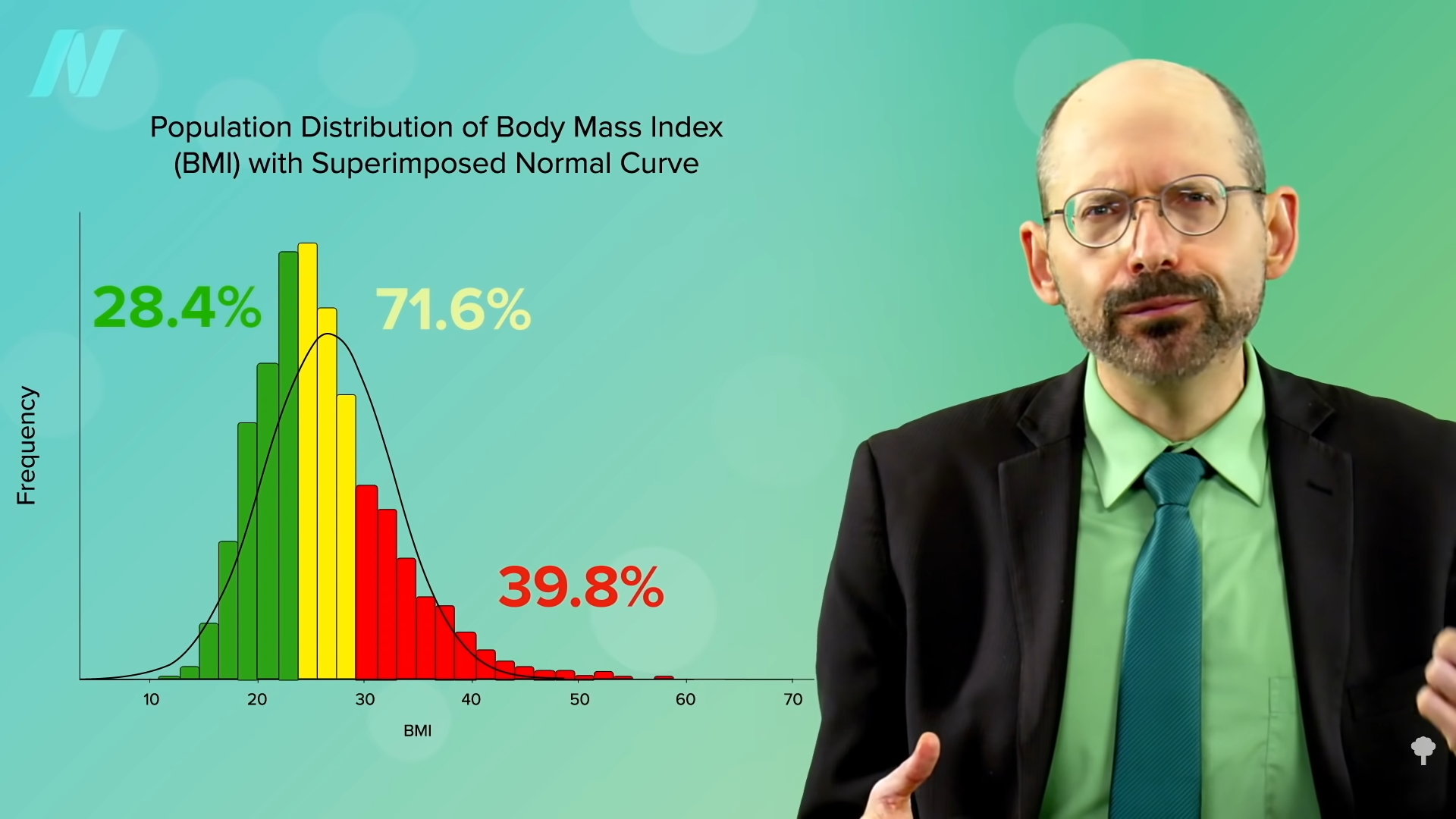

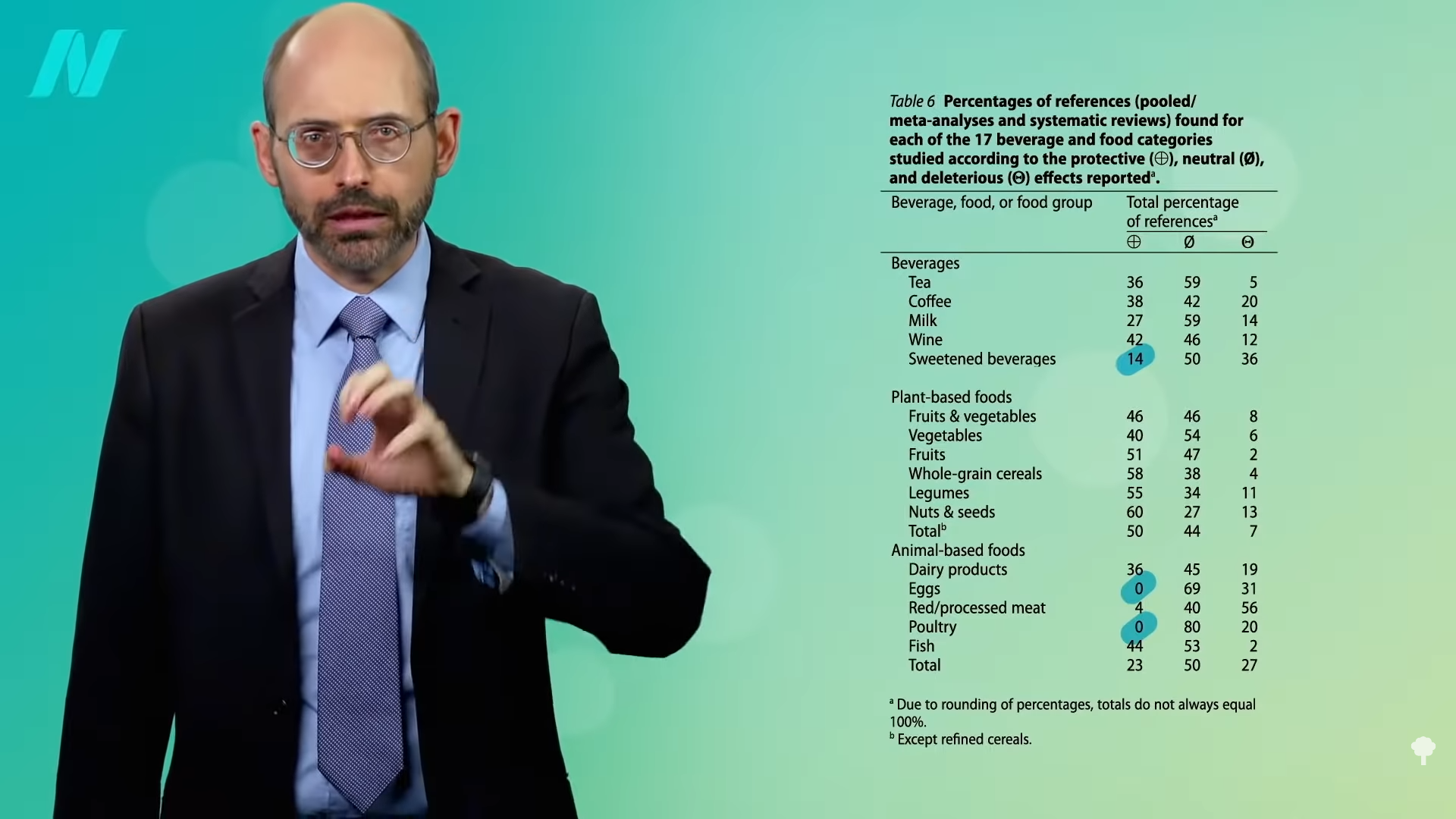

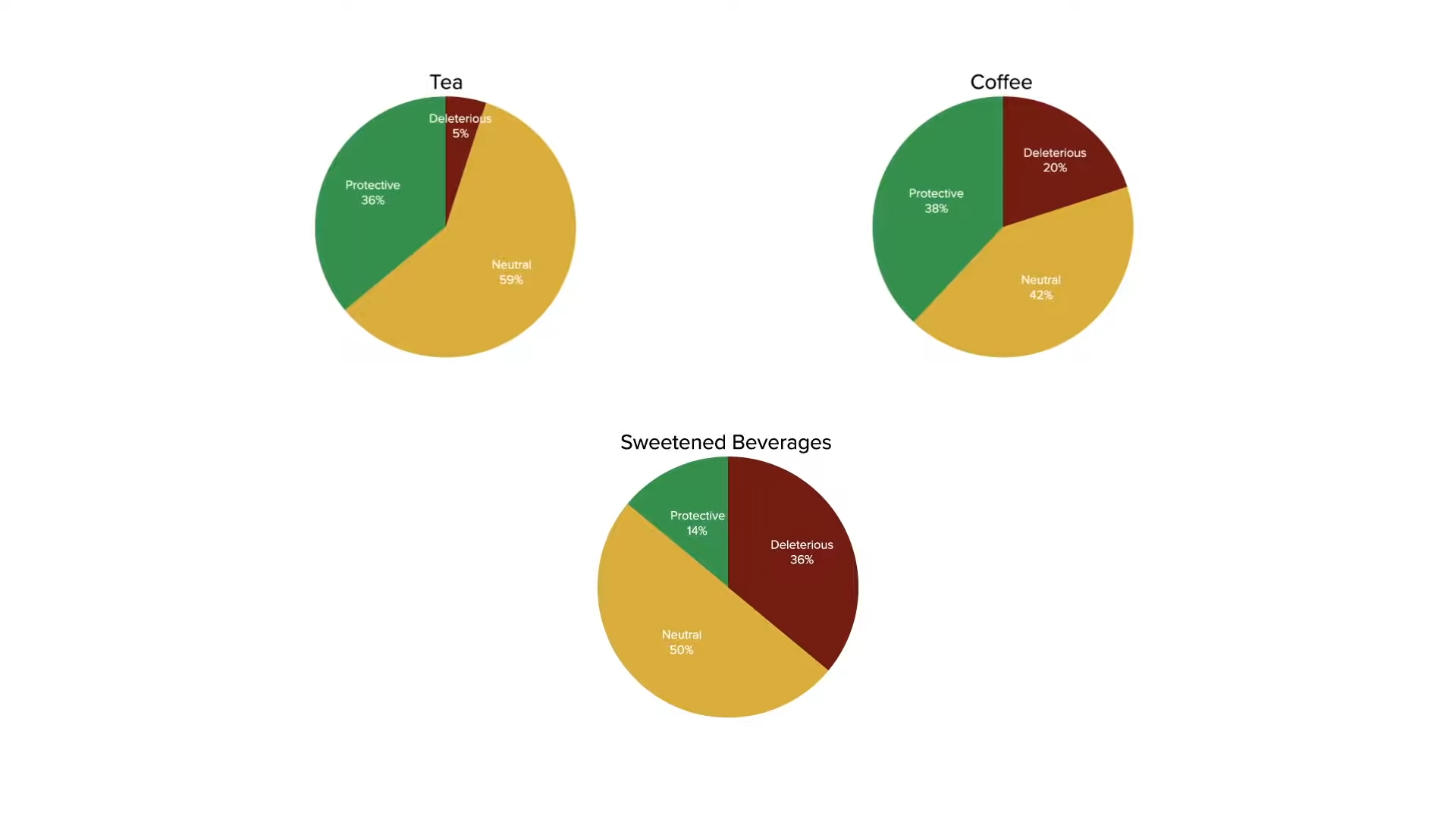

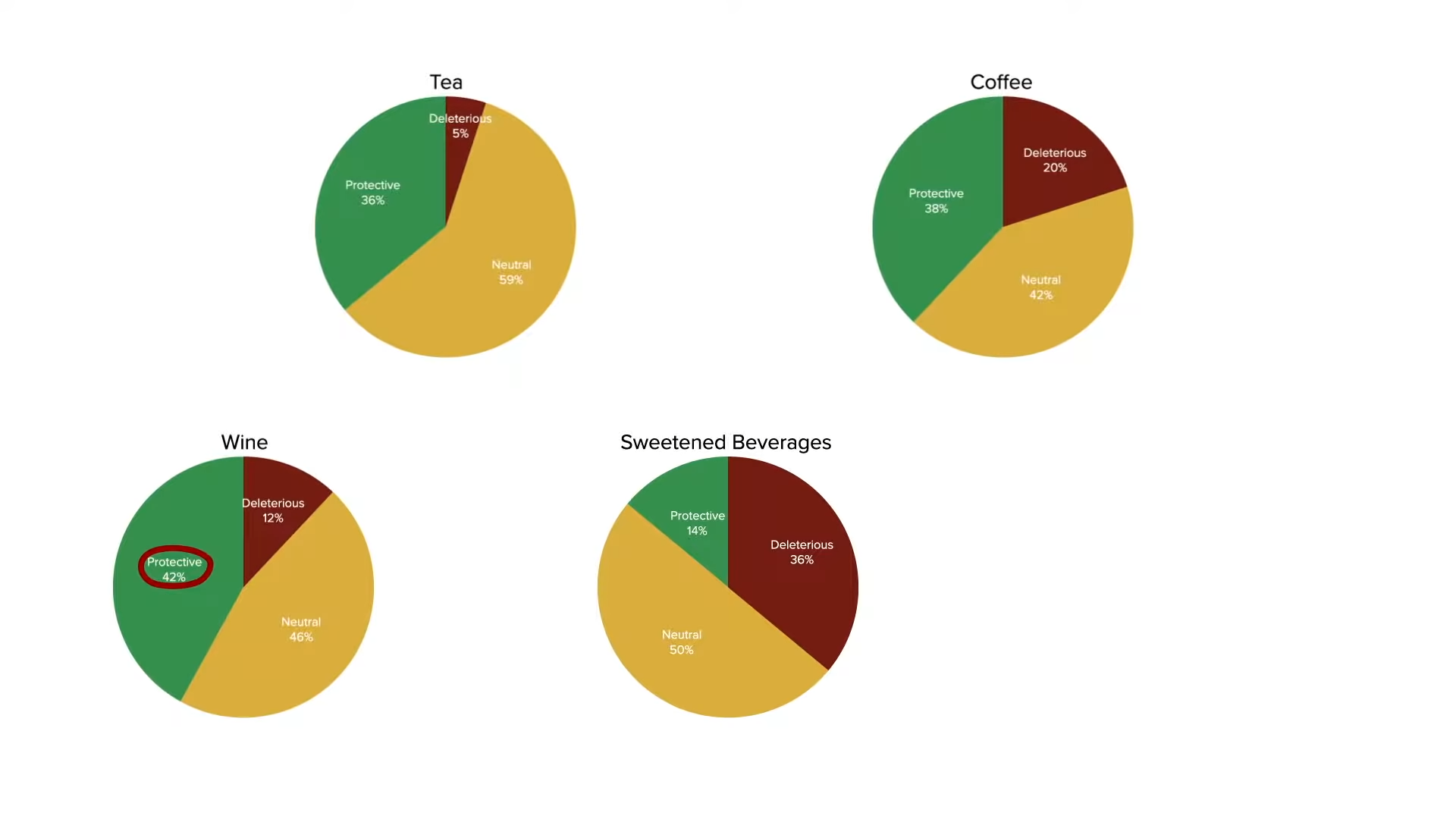

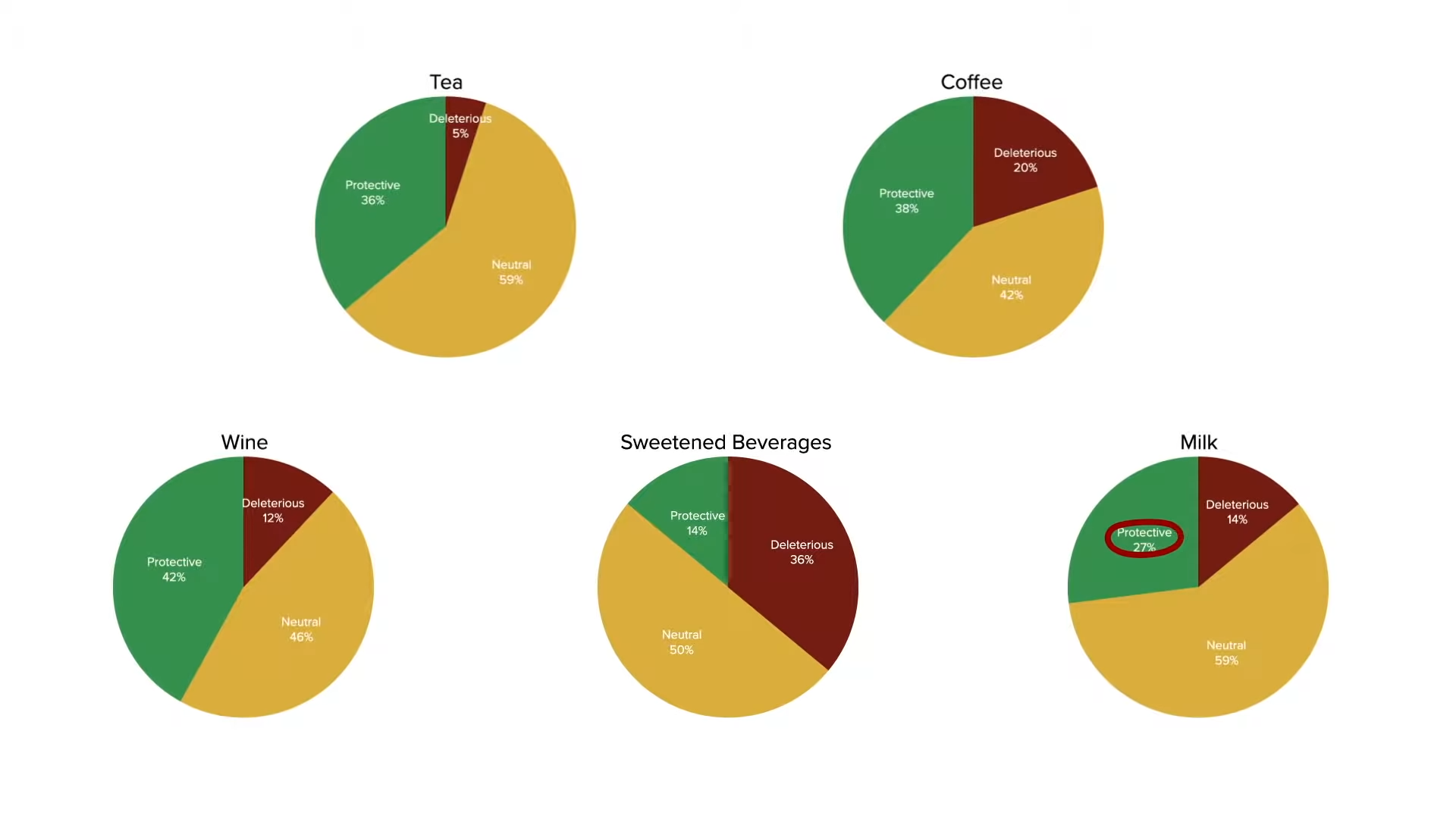

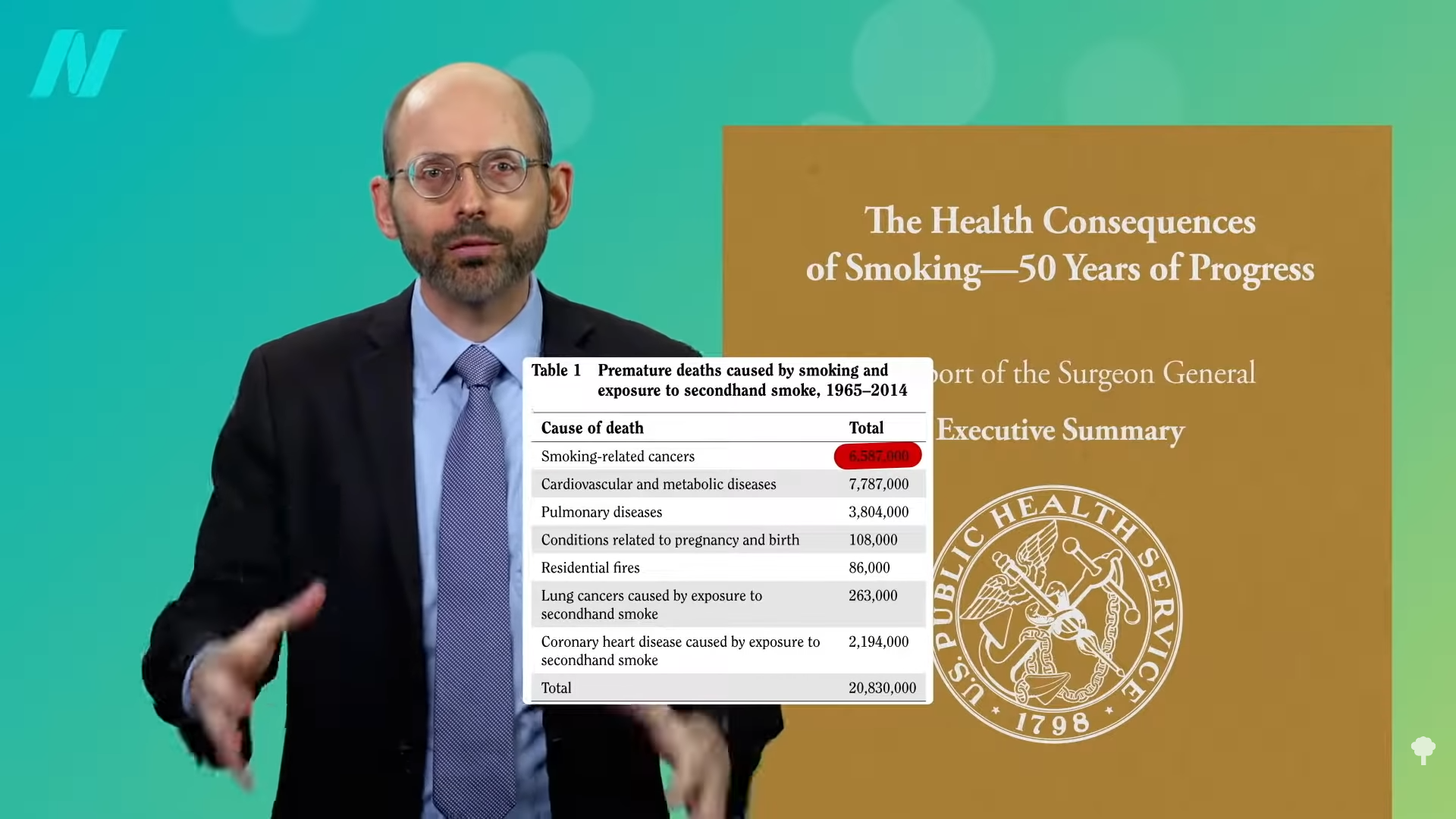

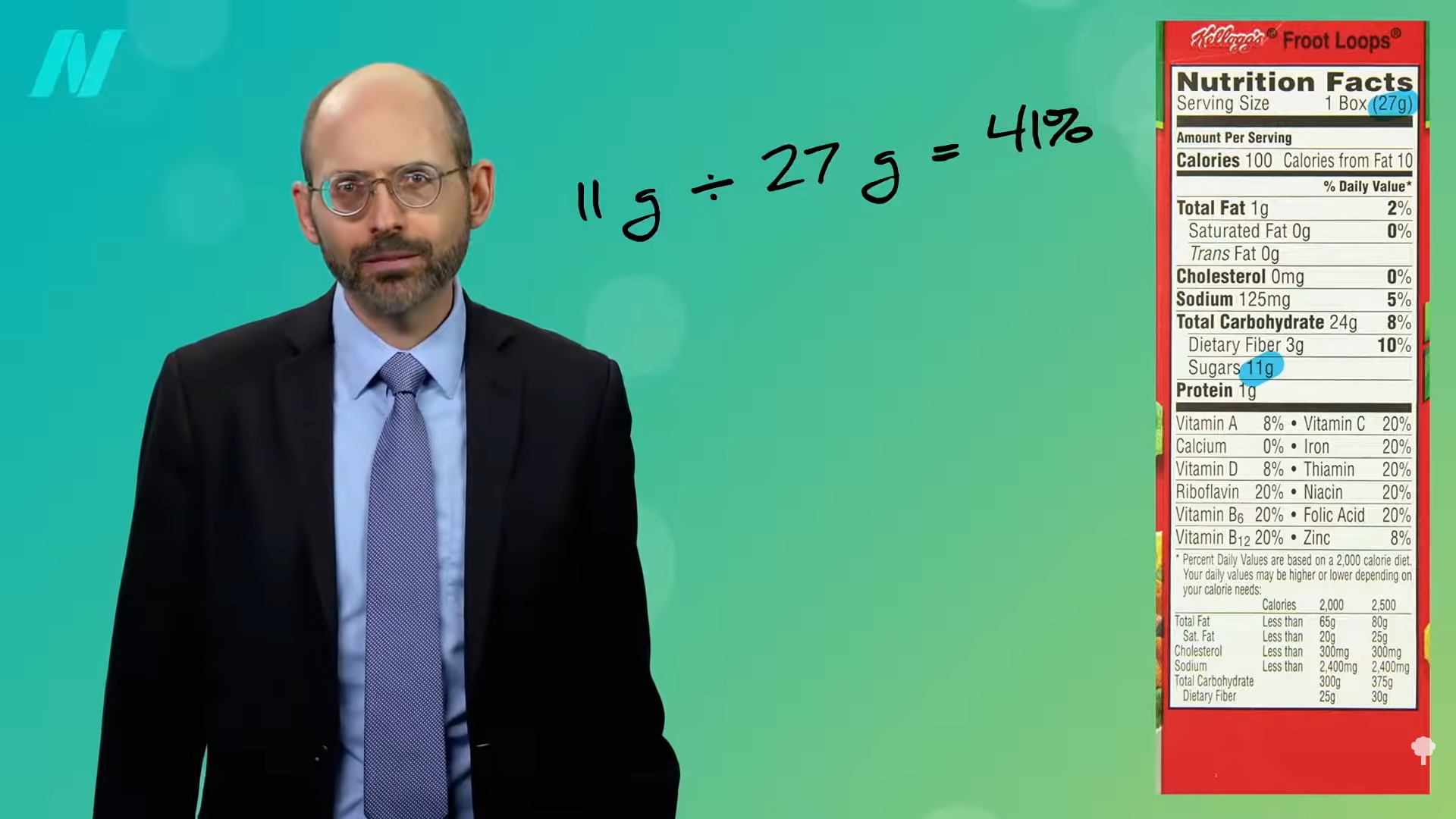

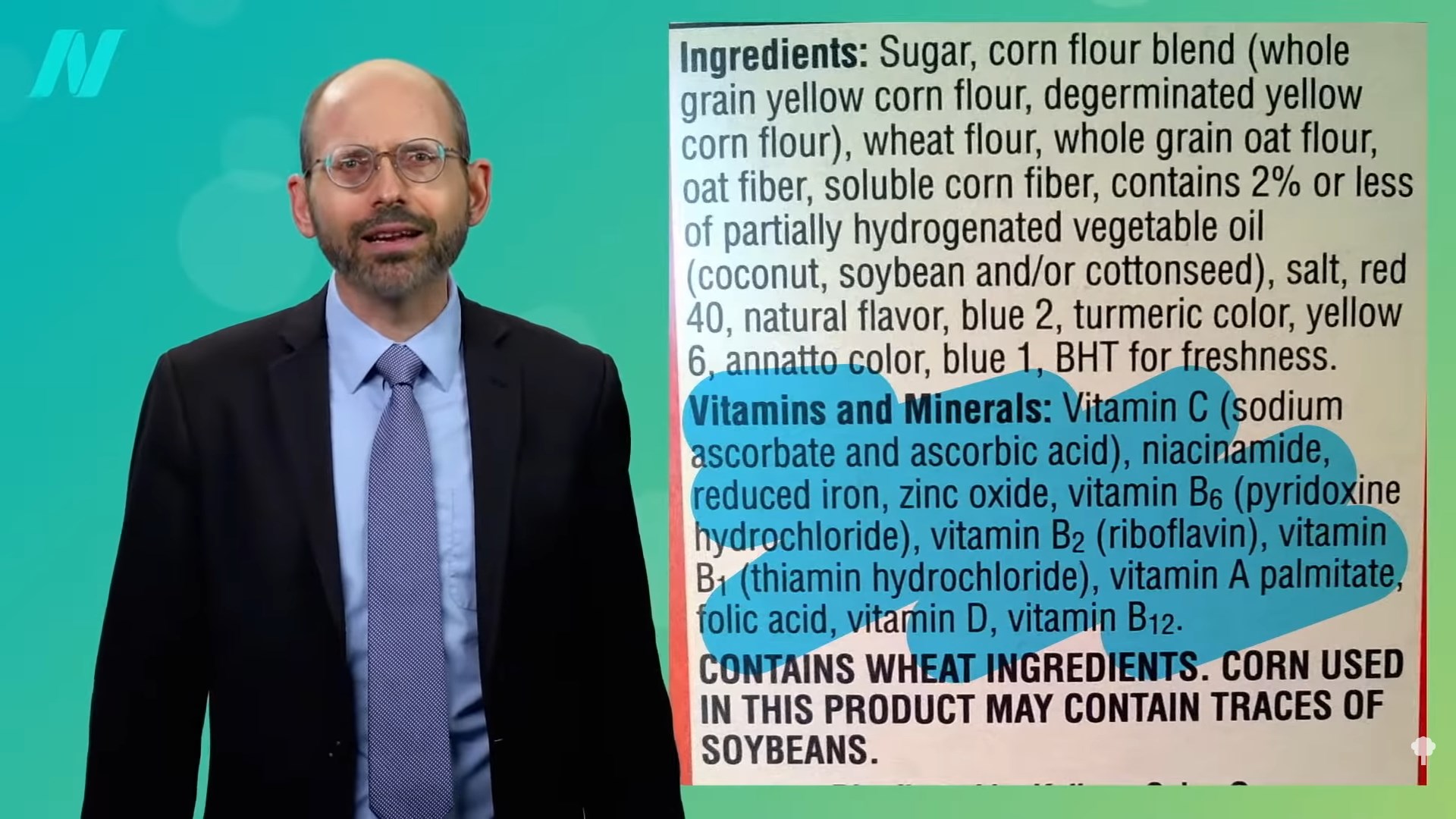

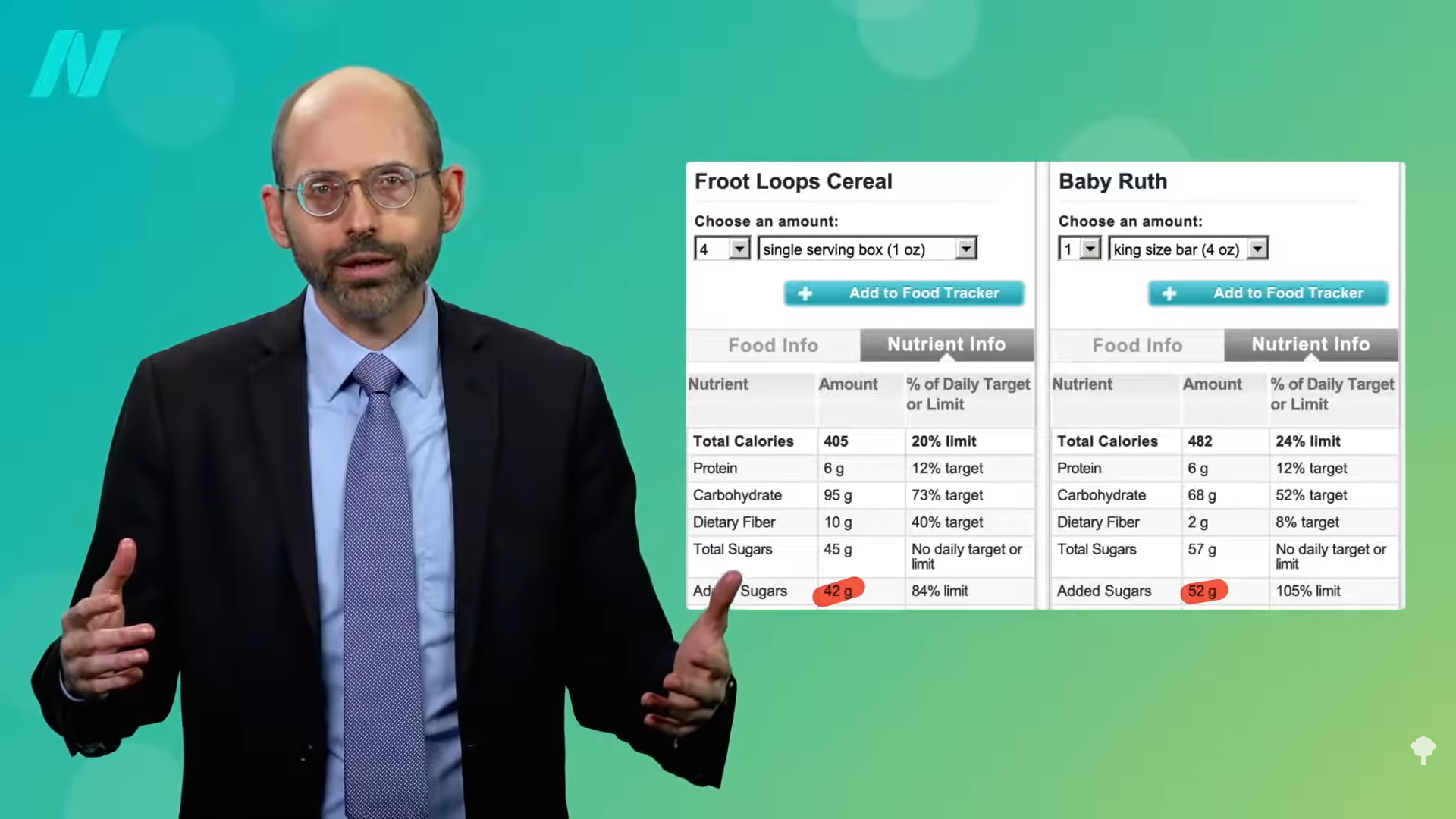

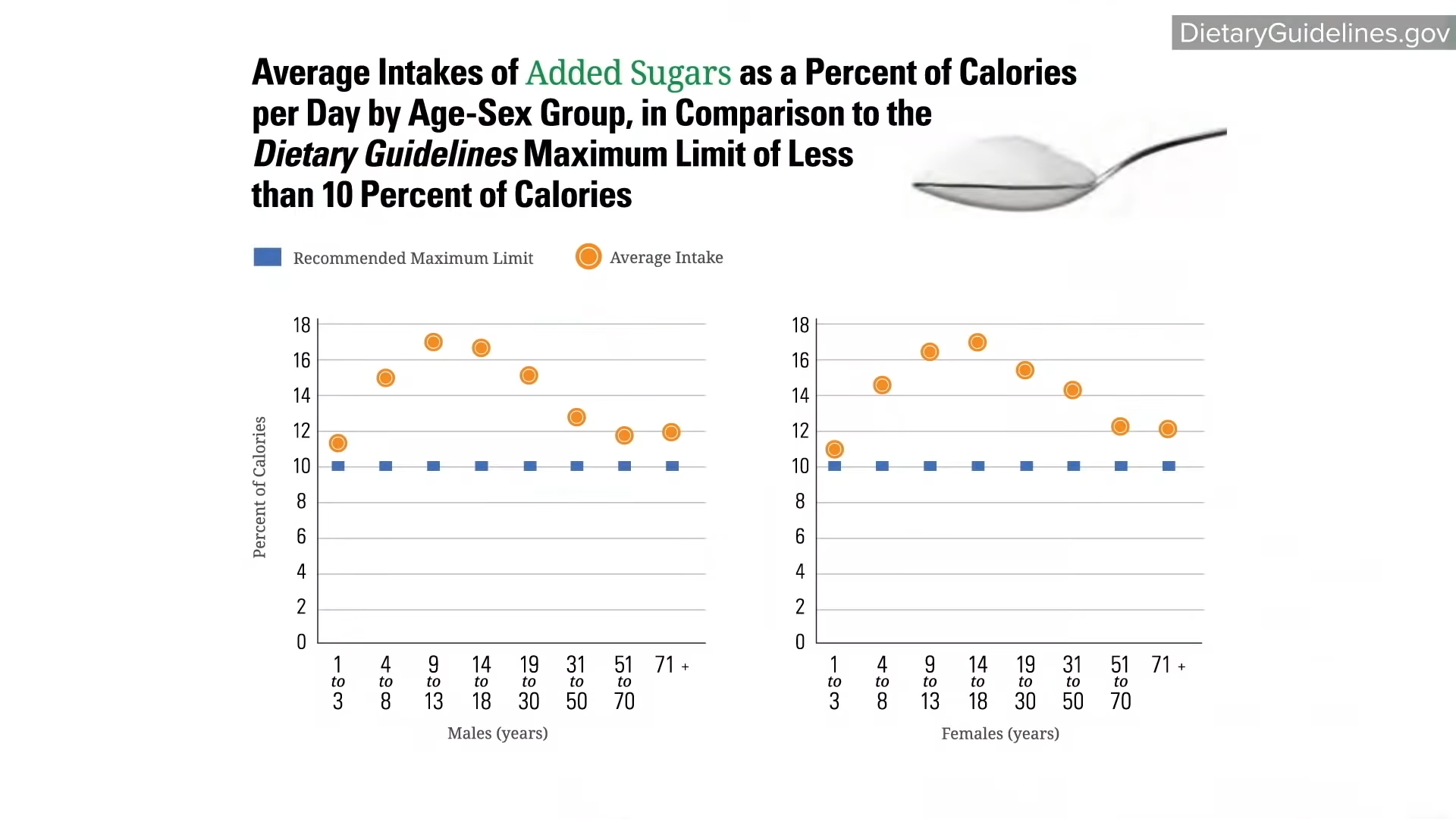

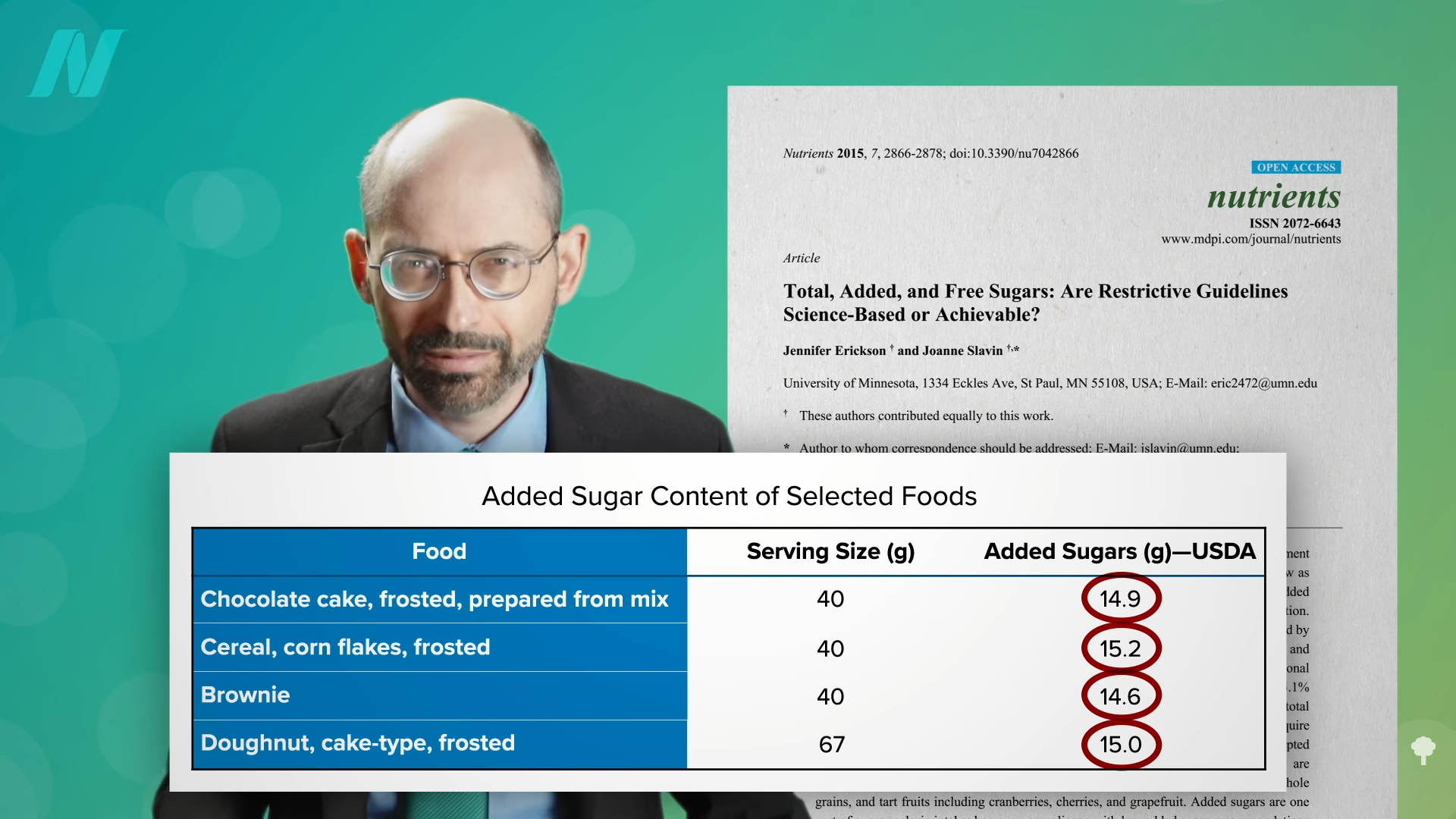

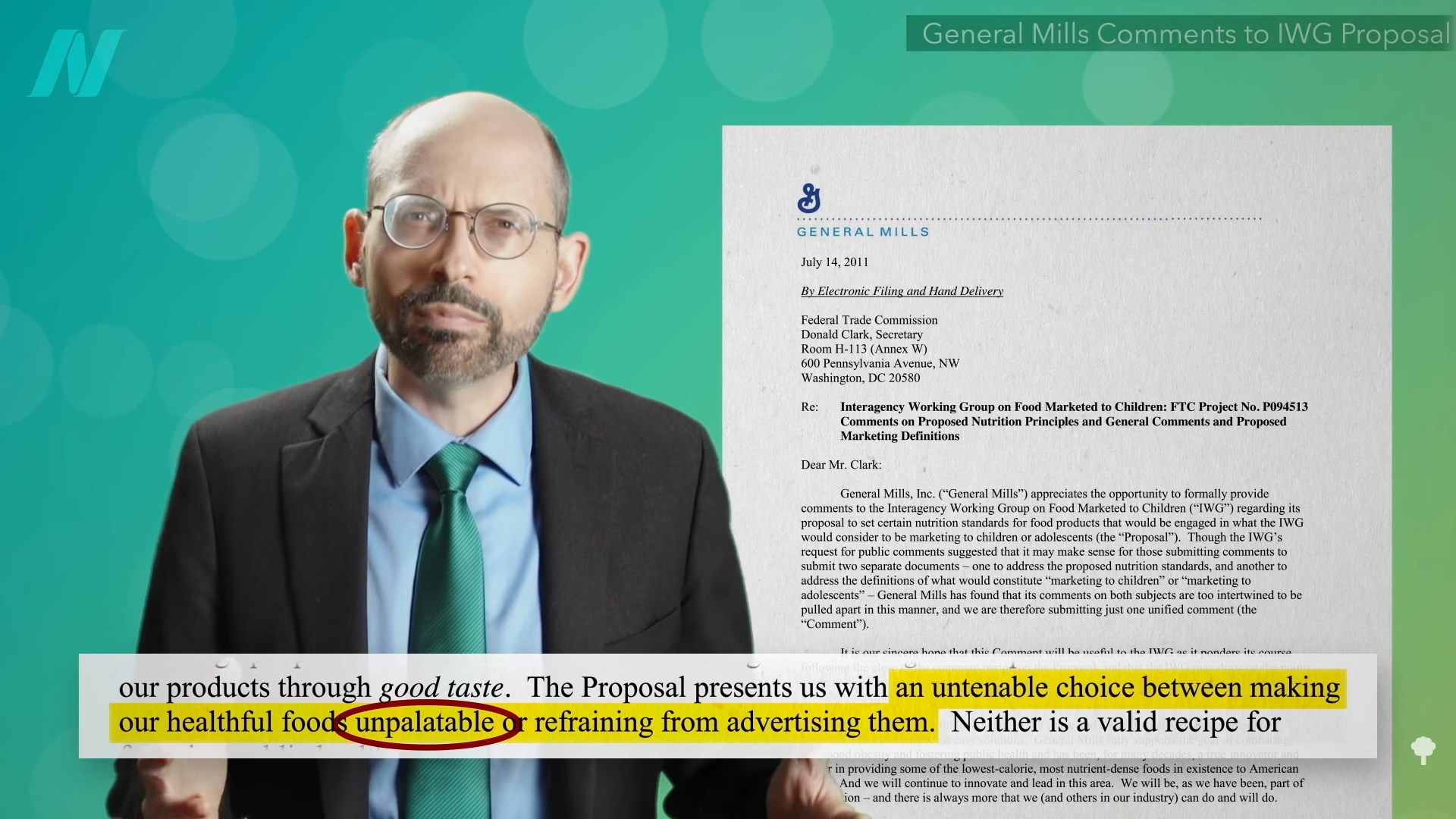

“When ranked in order of importance, among the interventions available to prevent stroke, the three most important are probably diet, smoking cessation, and blood pressure control.” Most of us these days are doing pretty good about not smoking, but less than half of us exercise enough. And, according to the American Heart Association, only 1 in 1,000 Americans is eating a healthy diet and less than 1 in 10 is even eating a moderately healthy diet, as you can see in the graph below and at 0:41 in my video Do Vegetarians Really Have Higher Stroke Risk?. Why does it matter? It matters because “diet is an important part of stroke prevention. Reducing sodium intake, avoiding egg yolks, limiting the intake of animal flesh (particularly red meat), and increasing the intake of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and lentils….Like the sugar industry, the meat and egg industries spend hundreds of millions of dollars on propaganda, unfortunately with great success.”

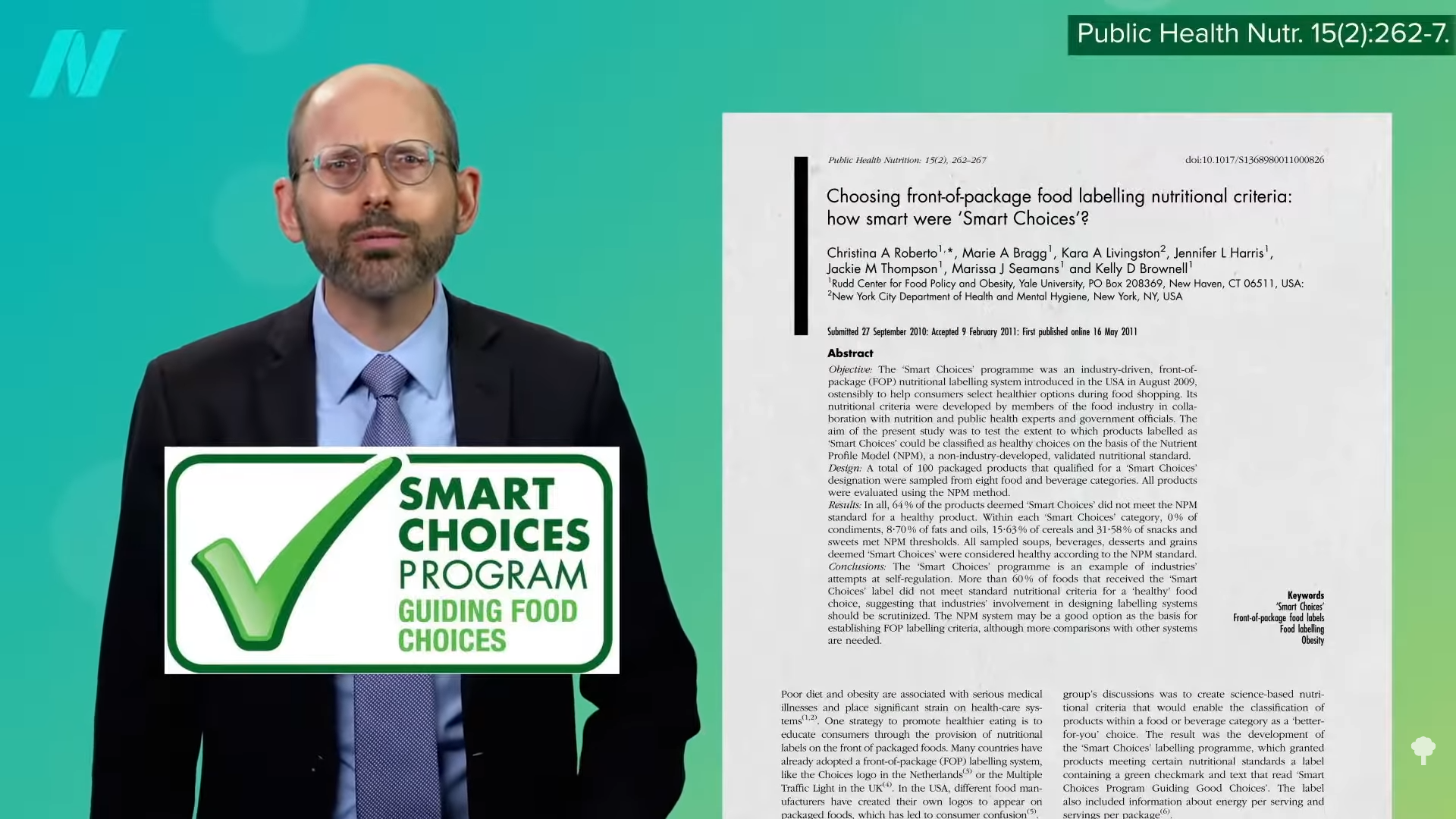

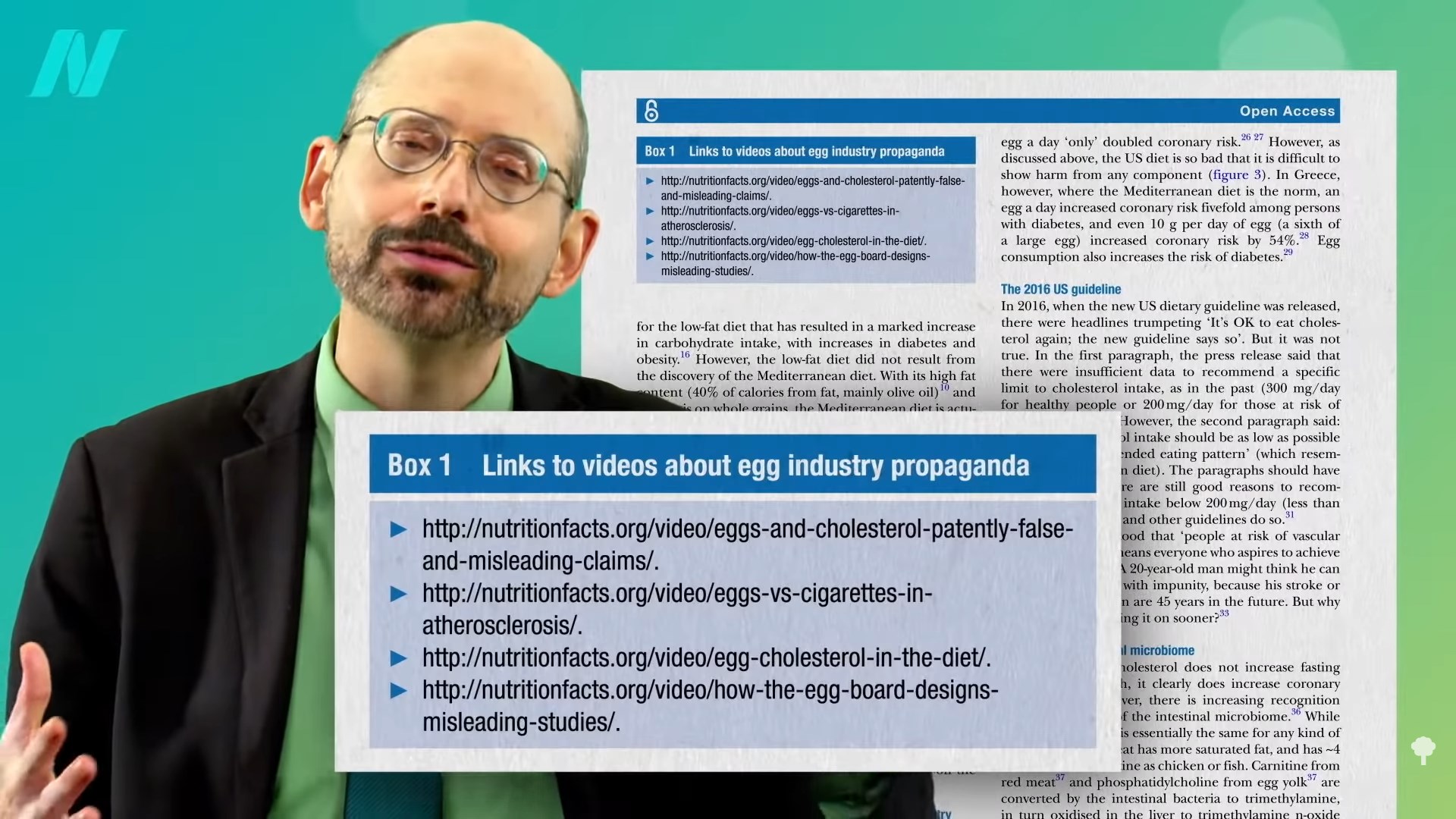

The paper goes on to say, “Box 1 provides links to information about the issue.” I was excited to click on the hyperlink for “Box 1” and was so honored to see four links to my videos on egg industry propaganda, as you can see below and at 1:08 in my video.

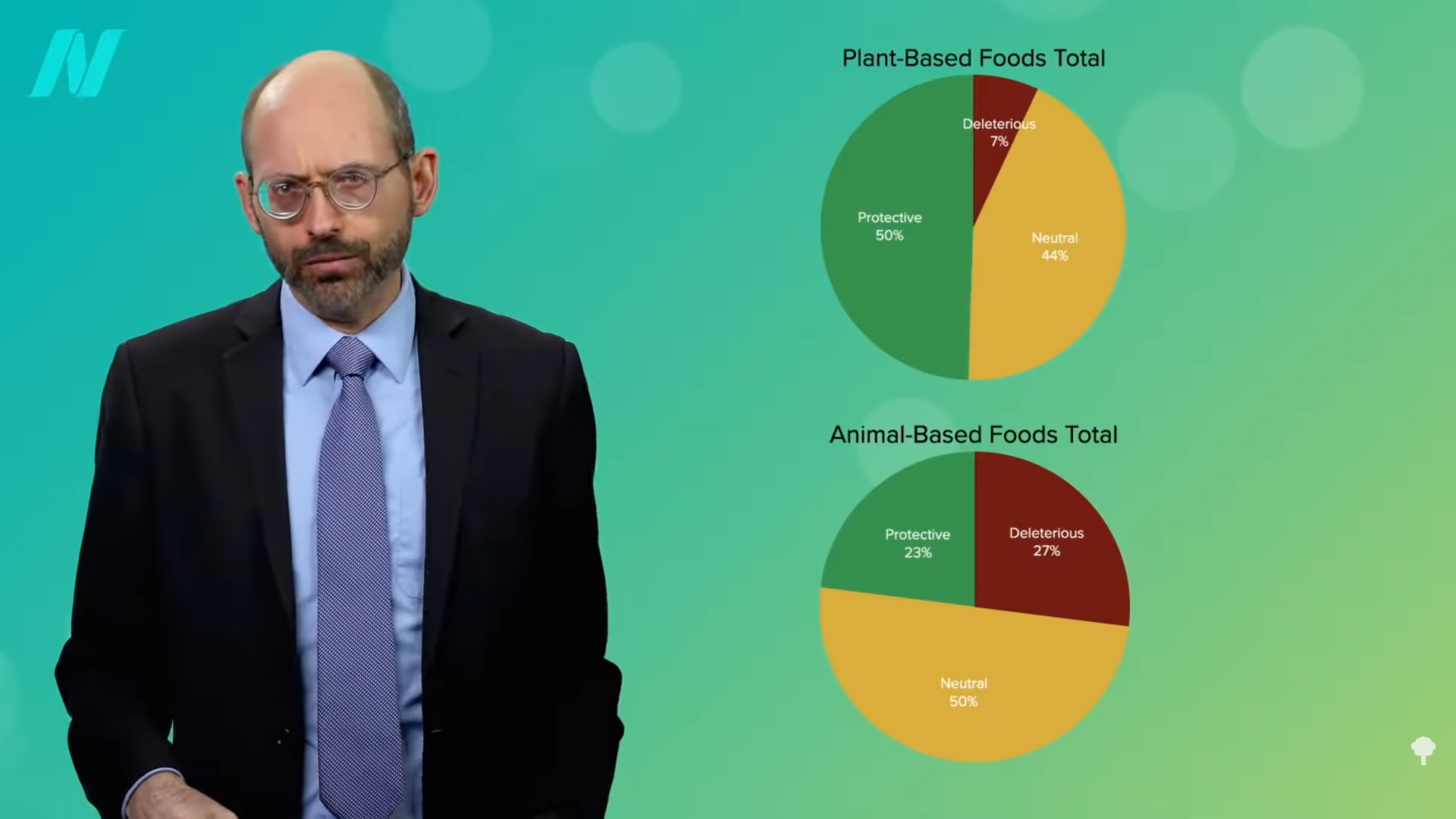

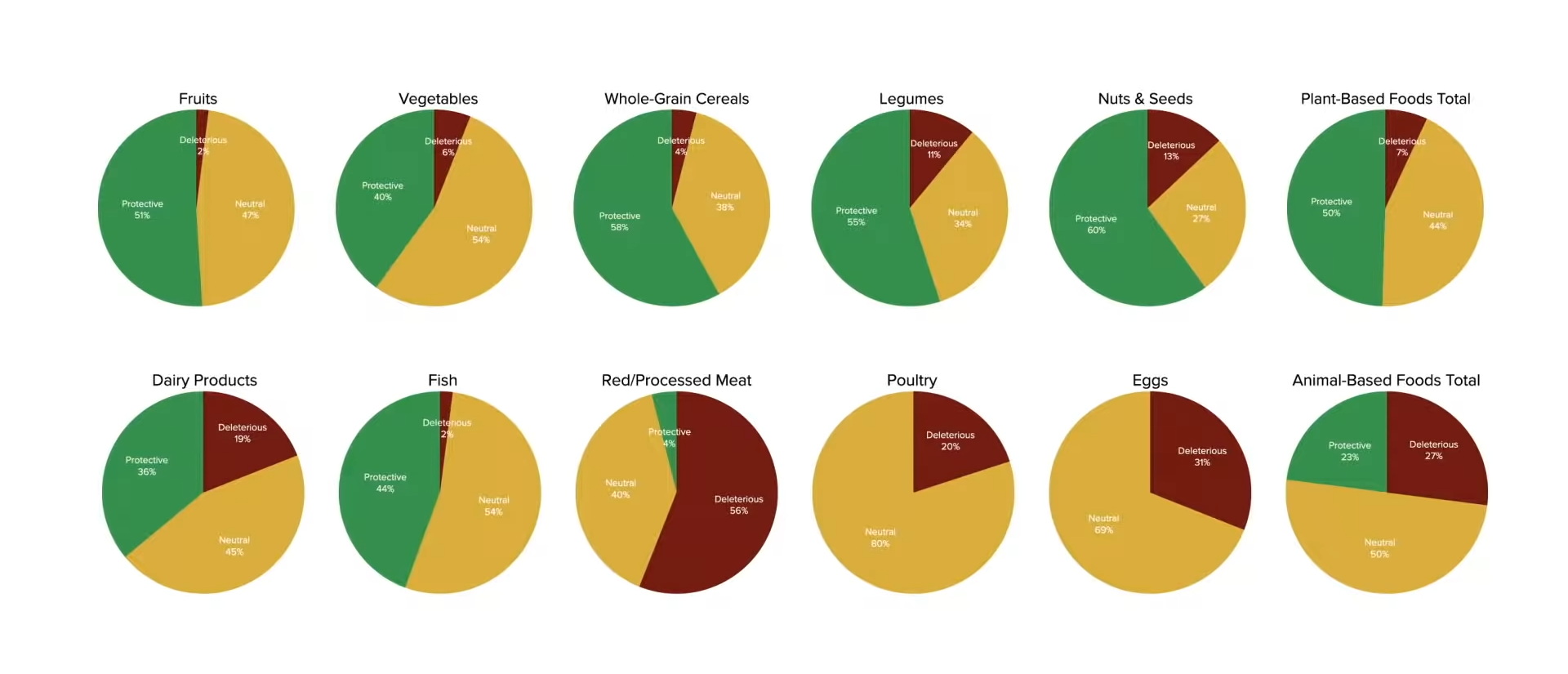

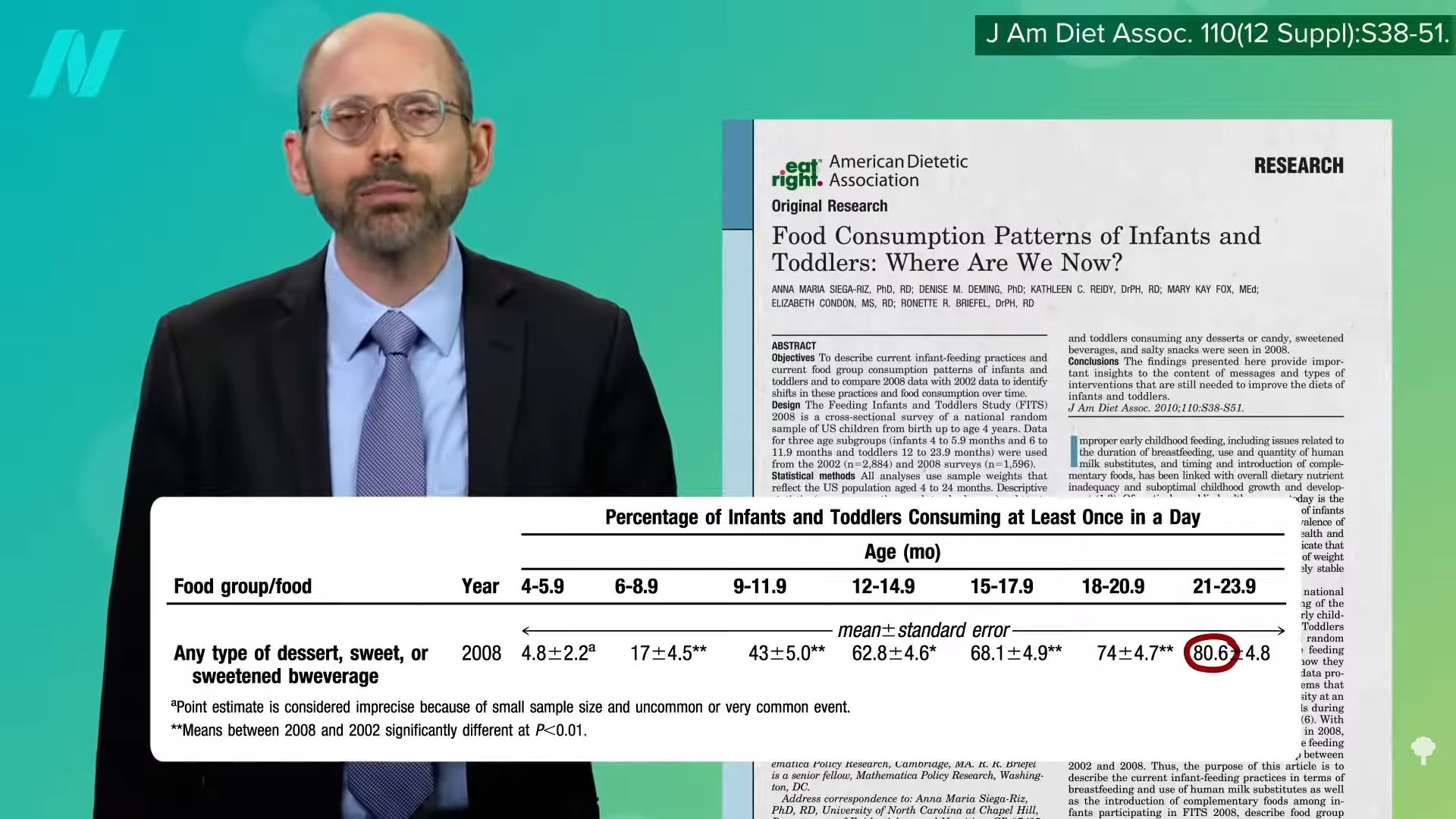

The strongest evidence for stroke protection lies in increasing fruit and vegetable intake, with more uncertainty regarding “the role of whole grains, animal products, and dietary patterns,” such as vegetarian diets. One would expect meat-free diets would do great. Meta-analyses have found that vegetarian diets lower cholesterol and blood pressure, as well as enhance weight loss and blood sugar control, and vegan diets may work even better. All the key biomarkers are going in the right direction. Given this, you may be surprised to learn that there hadn’t been any studies on the incidence of stroke in vegetarians and vegans until now. And if you think that is surprising, wait until you hear the results.

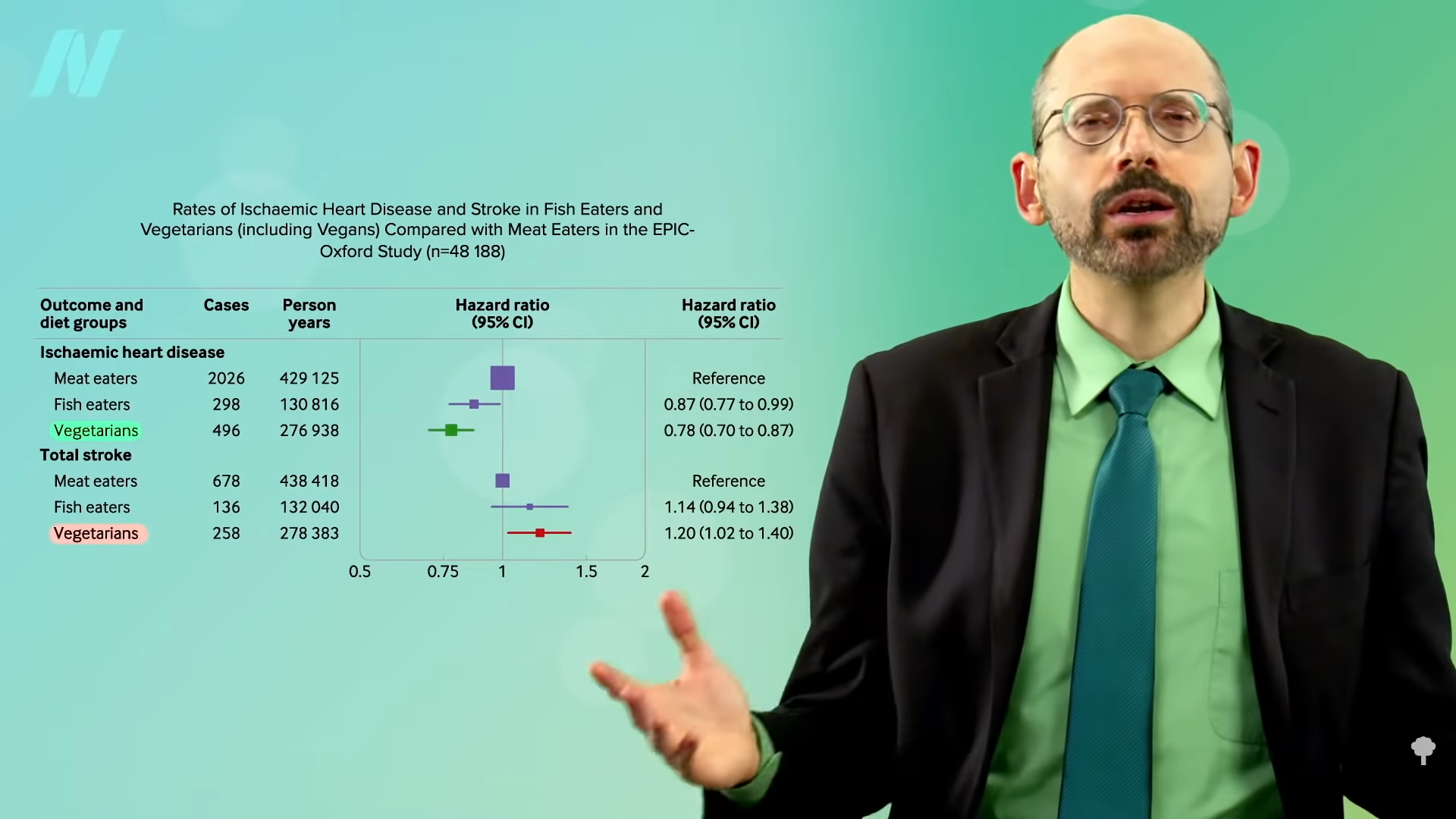

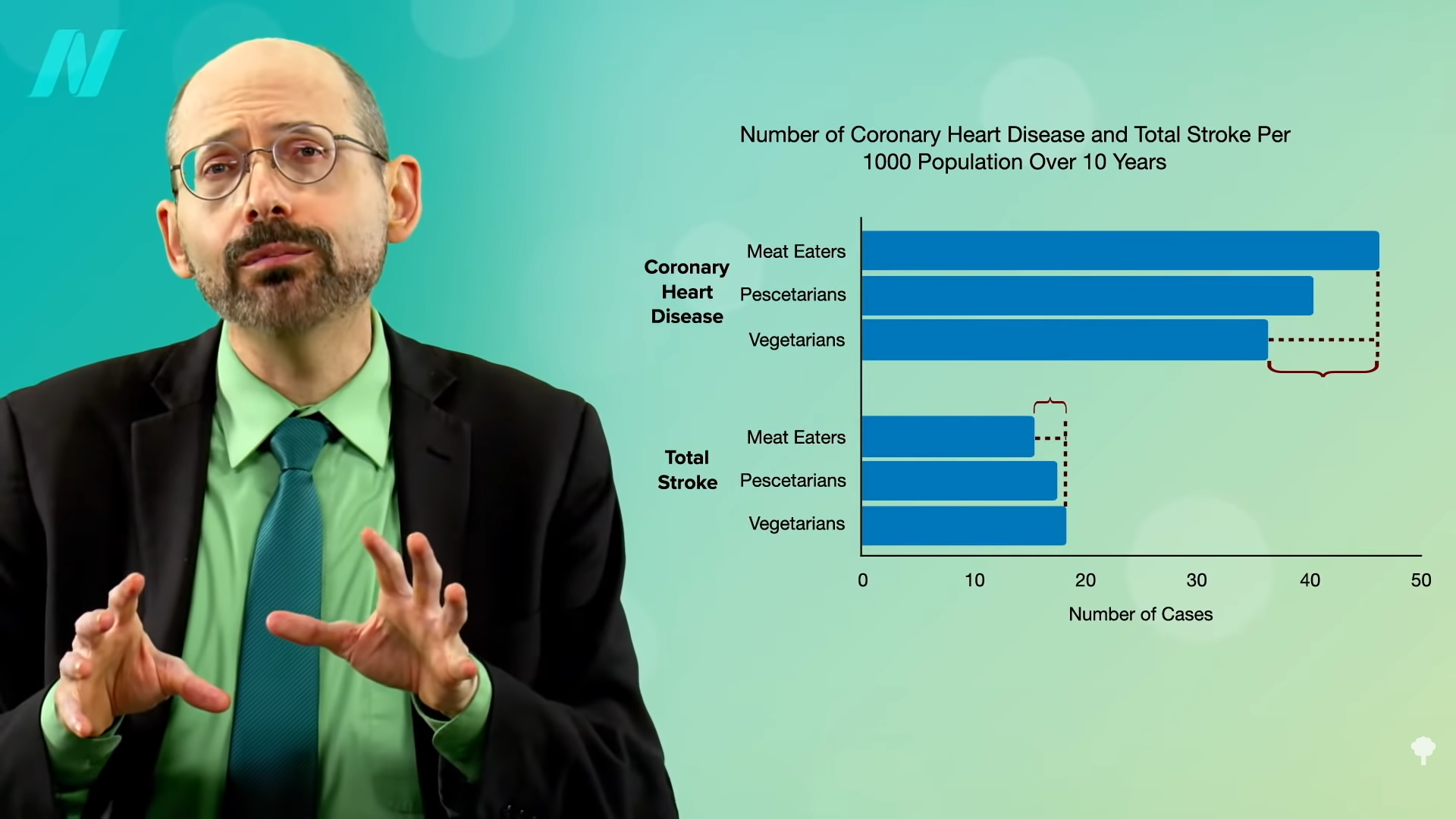

“Risks of Ischaemic Heart Disease and Stroke in Meat Eaters, Fish Eaters, and Vegetarians Over 18 Years of Follow-Up: Results from the Prospective EPIC-Oxford Study”: There was less heart disease among vegetarians (by which the researchers meant vegetarians and vegans combined). No surprise. Been there, done that. But there was more stroke, as you can see below, and at 2:14 in my video.

An understandable knee-jerk reaction might be: Wait a second, who did this study? Was there a conflict of interest? This is EPIC-Oxford, world-class researchers whose conflicts of interest may be more likely to read: “I am a member of the Vegan Society.”

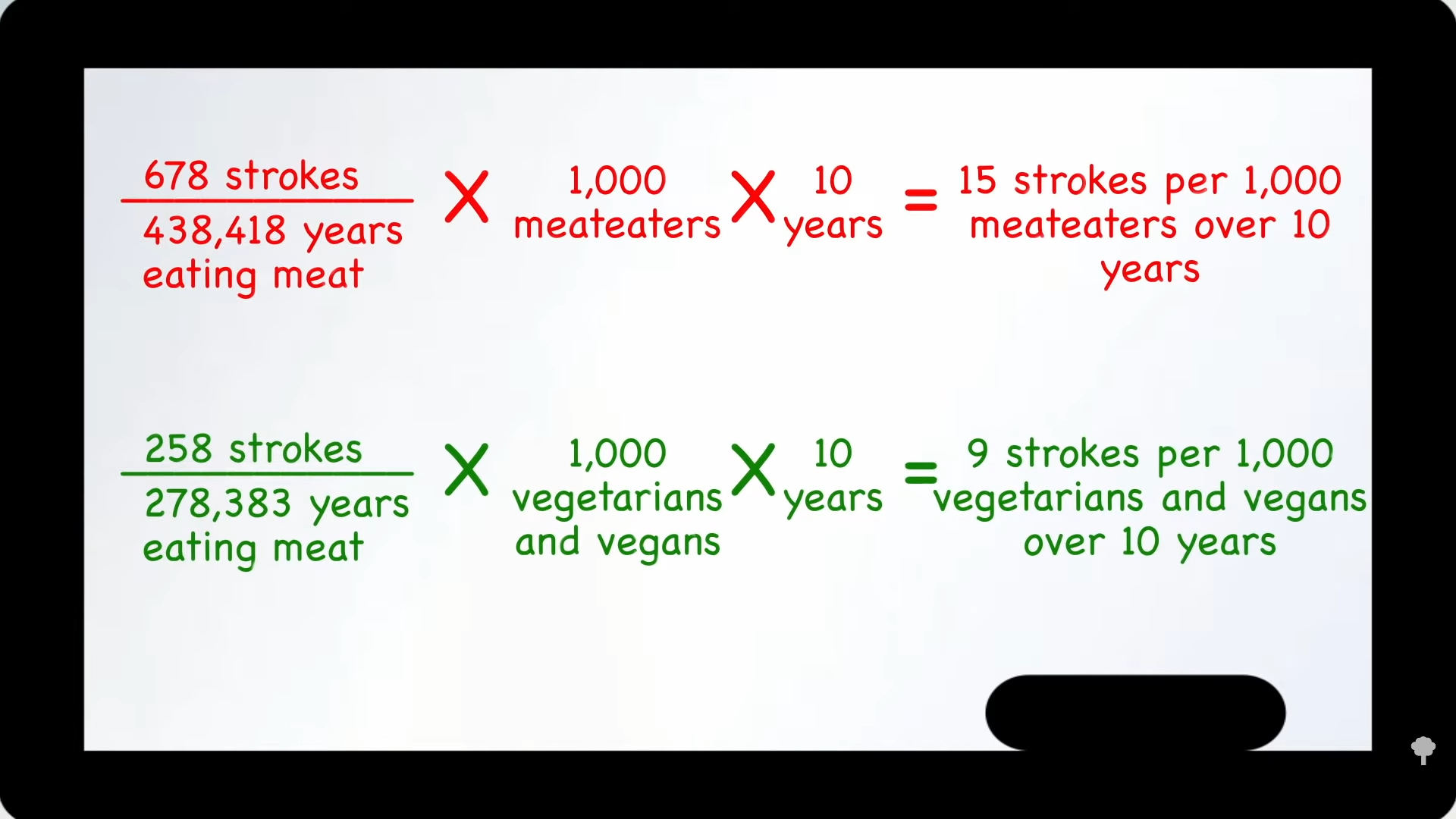

What about overadjustment? When the numbers over ten years were crunched, the researchers found 15 strokes for every 1,000 meat eaters, compared to only 9 strokes for every 1,000 vegetarians and vegans, as you can see below and at 2:41 in my video. In that case, how can they say there were more strokes in the vegetarians? This was after adjusting for a variety of factors. The vegetarians were less likely to smoke, for example, so you’d want to cancel that out by adjusting for smoking to effectively compare the stroke risk of nonsmoking vegetarians to nonsmoking meat eaters. If you want to know how a vegetarian diet itself affects stroke rates, you want to cancel out these non-diet-related factors. Sometimes, though, you can overadjust.

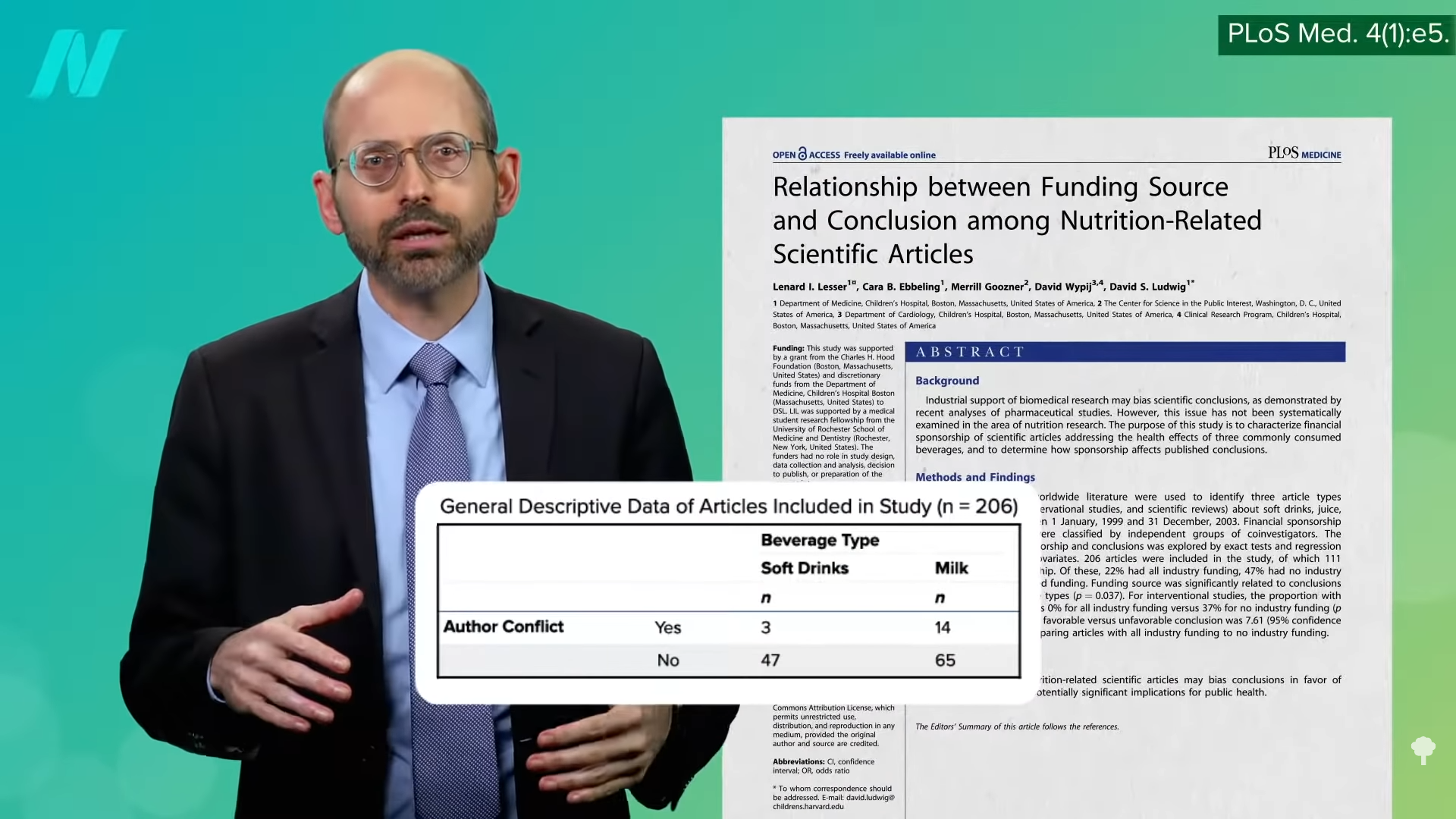

The sugar industry does this all the time. This is how it works: Imagine you just got a grant from the soda industry to study the effect of soda on the childhood obesity epidemic. What could you possibly do after putting all the studies together to conclude that there was a “near zero” effect of sugary beverage consumption on body weight? Well, since you know that drinking liquid candy can lead to excess calories that can lead to obesity, if you control for calories, if you control for a factor that’s in the causal chain, effectively only comparing soda drinkers who take in the same number of calories as non-soda-drinkers, then you could undermine the soda-to-obesity effect, and that’s exactly what they did. That introduces “over adjustment bias.” Instead of just controlling for some unrelated factor, you control for an intermediate variable on the cause-and-effect pathway between exposure and outcome.

Overadjustment is how meat and dairy industry-funded researchers have been accused of “obscuring true associations” between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease. We know that saturated fat increases cholesterol, which increases heart disease risk. Therefore, if you control for cholesterol, effectively only comparing saturated fat eaters with the same cholesterol levels as non-saturated-fat eaters, that could undermine the saturated fat-to-heart disease effect.

Let’s get back to the EPIC-Oxford study. Since vegetarian eating lowers blood pressure and a lowered blood pressure leads to less stroke, controlling for blood pressure would be an overadjustment, effectively only comparing vegetarians to meat eaters with the same low blood pressure. That’s not fair, since lower blood pressure is one of the benefits of vegetarian eating, not some unrelated factor like smoking. So, that would undermine the afforded protection. Did the researchers do that? No. They only adjusted for unrelated factors, like education, socioeconomic class, smoking, exercise, and alcohol. That’s what you want. You want to tease out the effects of a vegetarian diet on stroke risk. You want to try to equalize everything else to tease out the effects of just the dietary choice. And, since the meat eaters in the study were an average of ten years older than the vegetarians, you can see how vegetarians could come out worse after adjusting for that. Since stroke risk can increase exponentially with age, you can see how 9 strokes among 1,000 vegetarians in their 40s could be worse than 15 strokes among 1,000 meat-eaters in their 50s.

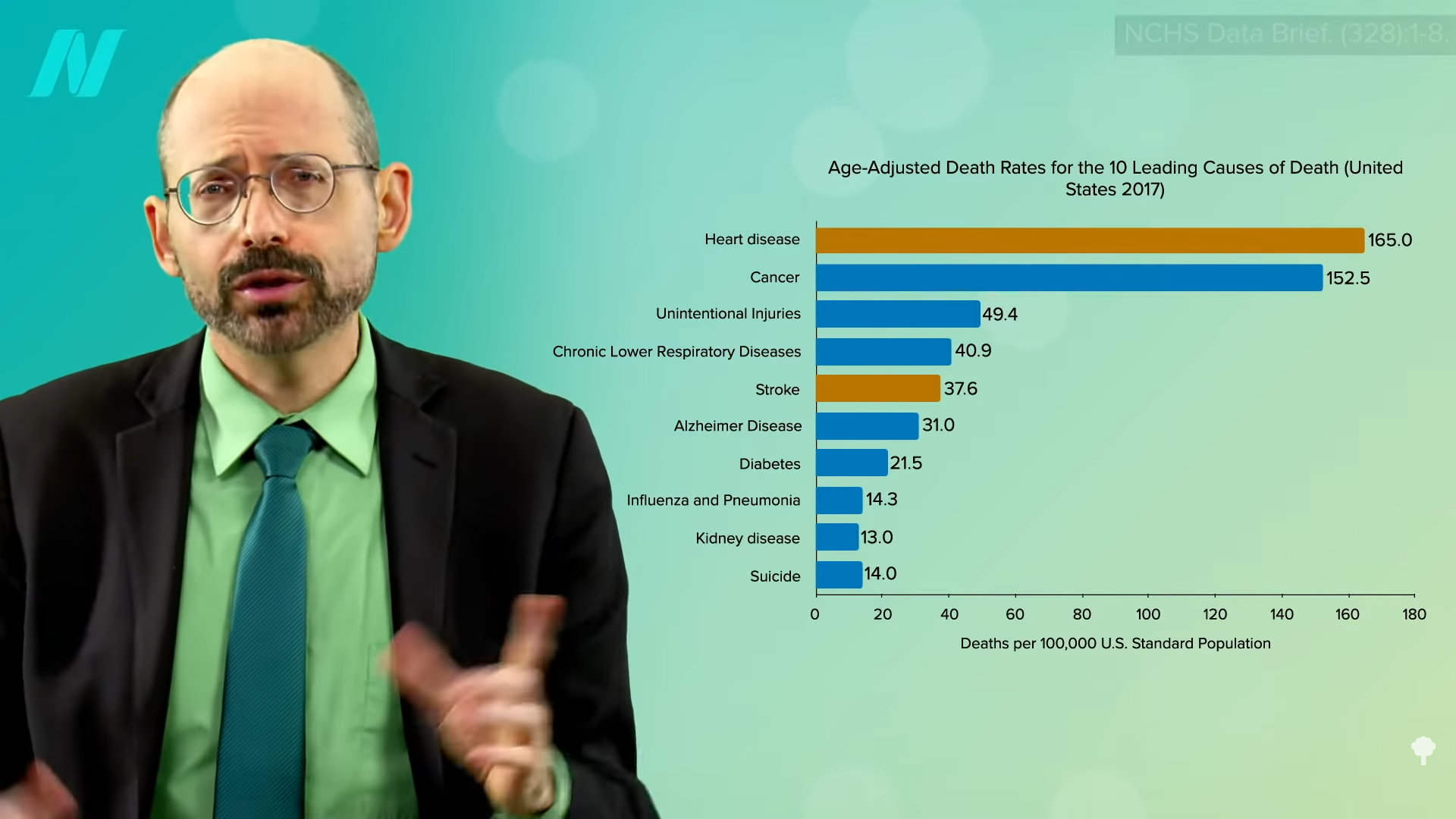

The fact that vegetarians had greater stroke risk despite their lower blood pressure suggests there’s something about meat-free diets that so increases stroke risk it’s enough to cancel out the blood pressure benefits. But, even if that’s true, you would still want to eat that way. As you can see in the graph below and at 6:16 in my video, stroke is our fifth leading cause of death, whereas heart disease is number one.

So, yes, in the study, there were more cases of stroke in vegetarians, but there were fewer cases of heart disease, as you can see below and at 6:29. If there is something increasing stroke risk in vegetarians, it would be nice to know what it is in hopes of figuring out how to get the best of both worlds. This is the question we will turn to next.

I called it 21 years ago. There’s an old video of me on YouTube where I air my concerns about stroke risk in vegetarians and vegans. (You can tell it’s from 2003 by my cutting-edge use of advanced whiteboard technology and the fact that I still had hair.) The good news is that I think there’s an easy fix.

This is the third in a 12-video series on stroke risk. Links to the others are in the related posts below.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link