MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay, Jul 24 (IPS) – At a meeting with European and Latin American leaders in Brussels this July, Brazil’s President Lula da Silva reiterated the bold commitment he had made in his first international speech as president-elect, when he attended the COP27 climate summit in November 2022: bringing Amazon deforestation down to zero by 2030.

Lula’s presence at COP27 was a signal to the world that Brazil was willing to become the climate champion it needs to be. Following a request by the Brazilian Forum of NGOs and Social Movements for Environment and Development, Lula offered to host the 2025 climate summit in Brazil; it has now been confirmed that COP30 will be held in Belém, gateway to the Amazon River.

At COP27 Lula also said he intended to revive and modernise the 45-year old Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organisation, a body bringing together the eight Amazonian countries – Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela – to take concerted steps to protect the Amazon rainforest.

Four years of regression

In his four years in office, Lula’s far-right climate-denier predecessor Jair Bolsonaro dismantled environmental protections and paralysed key environmental agencies by cutting their funding and staff. He vilified civil society, criminalised activists and discredited the media. He allowed deforestation to proceed at an astonishing pace and emboldened businesses to grab land, clear it for agriculture by starting fires and carry out illegal logging and mining.

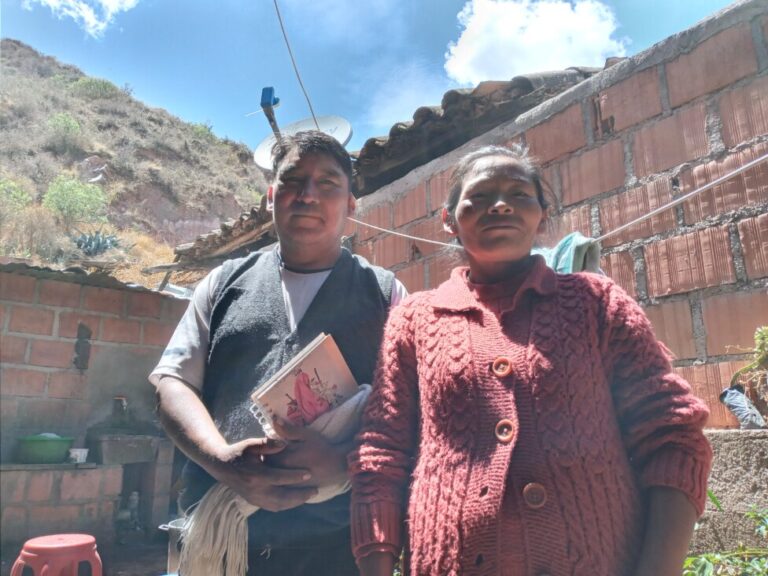

Under Bolsonaro, already embattled Indigenous communities and activists became even more vulnerable to attacks. By encouraging environmental plunder, including on protected and Indigenous land, the government enabled violence against environmental and Indigenous peoples’ rights defenders. A blatant example was the murder of Brazilian Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips in June 2022. The two were ambushed and killed on the orders of the head of an illegal transnational fishing network. Both the material and intellectual authors of the crimes have now been charged and await trial.

Reversing the regression

Having being elected on a promise to reverse environmental destruction, the new administration has sought to restructure and resource monitoring and enforcement institutions. It strengthened the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), the federal agency in charge of enforcing environmental policy, and the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI), which for the first time is now headed by an Indigenous person, Joenia Wapichana.

Bolsonaro had transferred FUNAI to the Ministry of Agriculture, run by a leader of the congressional agribusiness caucus. Instead of protecting Indigenous land, it enabled deforestation and the expansion of agribusiness.

In contrast, Lula’s first political gestures were to create a new ministry for Indigenous peoples’ affairs, appointing Indigenous leader Sonia Guajajara to lead it, and to make Marina Silva, a leader of the environmentalist party Rede Sustentabilidade, Minister for the Environment, a position she had held between 2003 and 2008.

Lula also restored the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon, launched in 2004 and implemented until Bolsonaro took over. In February, the government set up a Permanent Inter-Ministerial Commission for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation and Fires in Brazil to coordinate actions across 19 ministries and develop zero deforestation policies.

The strategy establishes a permanent federal government presence in vulnerable areas with the aim of eliminating illegal activities, setting up bases and using intelligence and satellite imagery to track criminal activity.

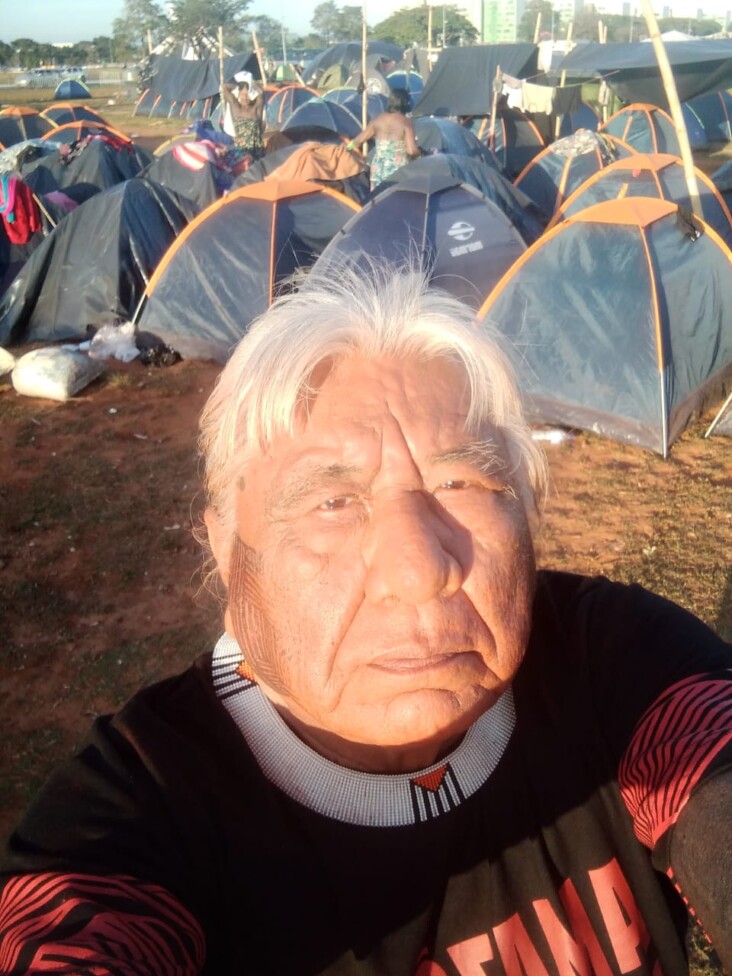

The newly appointed Federal Police’s Director for the Amazon and the Environment, Humberto Freire, launched a campaign to rid protected Indigenous land of illegal miners. It appears to be paying off: in July he announced that around 90 per cent of miners operating in Yanomami territory, Brazil’s largest protected Indigenous land, had been expelled. According to police sources, there were 19 mine-related deforestation alerts in April 2023 – compared to 444 in April 2022.

But the fight isn’t over. There are still a couple of thousand miners active and the criminal enterprises employing them remain very much alive. The key task of recovering damaged land and rivers can only begin once they’re all driven away for good. And an issue that cries out for international cooperation remains unresolved: violence and environmental degradation continue unabated in Yanomami communities across the border in Venezuela, and will only increase as illegal miners jump jurisdictions.

Achieving the ambitious zero-deforestation goal will require efforts on a much bigger scale than those of the past. And such efforts will further antagonise very powerful people.

Obstacles ahead

With the environmental agenda back on track, the pace of Amazon deforestation slowed down in the first six months of 2023, falling by 34 per cent compared to the same period in 2022. However, numbers still remain high and reductions are uneven, with two states – Roraima and Tocantins – showing increases. Deforestation is also still rising in another important part of Brazil’s environment, the Cerrado, where preservation areas are few and most deforestation happens on private properties.

For the Amazon, a crucial test will come in the second half of the year, when temperatures are higher. A stronger El Niño phase, with warming waters in the Pacific Ocean, will make the weather even drier and hotter than usual, helping fires spread fast. Anticipating this, IBAMA has scaled up its recruitment of firefighters to expand brigades in Indigenous and Black communities and conduct inspections and impose fines and embargoes. To discourage people from starting fires to clear land for agriculture, the agency prevents them putting that land to agricultural use.

But in the meantime, Brazil’s Congress has gone on the offensive. In June, the Senate made radical amendments to the bill on ministries sent by Lula, diluting the powers of the Ministries of Indigenous Peoples and Environment and limiting demarcation of Indigenous lands to those already occupied by communities by 1998, when the current constitution was enacted.

Indigenous leaders have complained that many communities weren’t on their land in 1998 because they’d been expelled over the course of centuries, and particularly during the 1964-1985 military dictatorship. They denounced the new law as ‘legal genocide’ and urged the president to veto it. Civil society has taken to the streets and social media to support the government’s environmental policies.

They face a formidable enemy. A recent report by the Brazilian Intelligence Agency exposed the political connections of illegal mining companies. Two business leaders directly associated with this criminal activity are active congressional lobbyists and maintain strong links with local politicians. They also stand accused of financing an attempted insurrection on 8 January.

Against these shady elites, civil society wields the most effective weapon at its disposal, shining a light on their dealings and letting them know that Brazil and the world are watching, and will remain vigilant for as long as it takes. The stakes are too high to drop the guard.

Inés M. Pousadela is CIVICUS Senior Research Specialist, co-director and writer for CIVICUS Lens and co-author of the State of Civil Society Report.

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Source link