Raw garlic is compared to roasted, stir-fried, simmered, and jarred garlic.

Garlic lowers blood pressure, regulates cholesterol, and stimulates immunity. I’ve talked before about its effect on heart disease risk factors, but what about immunity? Eating garlic appears to offer the best of both worlds, dampening the overreactive face of the immune system by suppressing inflammation while boosting protective immunity—for example, the activity of our natural killer cells, which our body uses to purge cells that have been stricken by viruses or cancer. “In World War II garlic was called ‘Russian Penicillin’ because, after running out of antibiotics, the soviet government turned to these ancient treatments for its soldiers,” but does it work? You don’t know until you put it to the test.

How about preventing the common cold? As I discuss in my video Benefits of Garlic for Fighting Cancer and the Common Cold, it is perhaps “the world’s most widespread viral infection, with most people suffering approximately two to five colds per year.” In the first study “to use a double-blind, placebo-controlled design to investigate prevention of viral disease with a garlic supplement,” those randomized to the garlic suffered 60 percent fewer colds and were affected 70 percent fewer days. So, those on garlic not only had fewer colds, but they also recovered faster, suffering only one and a half days instead of five. Accelerated relief, reduced symptom severity, and faster recovery to full fitness. Interesting, but that study was done about two decades ago. What about all of the other randomized controlled trials? There aren’t any. There’s only that one trial to date. Still, the best available balance of evidence suggests that, indeed, “garlic may prevent occurrences of the common cold.”

What about cancer? Is garlic “a stake through the heart of cancer?” As you can see below and at 2:05 in my video, various garlic supplements have been tested on cells in a petri dish or lab animals, but there weren’t any human studies to see if garlic could affect gene expression until now.

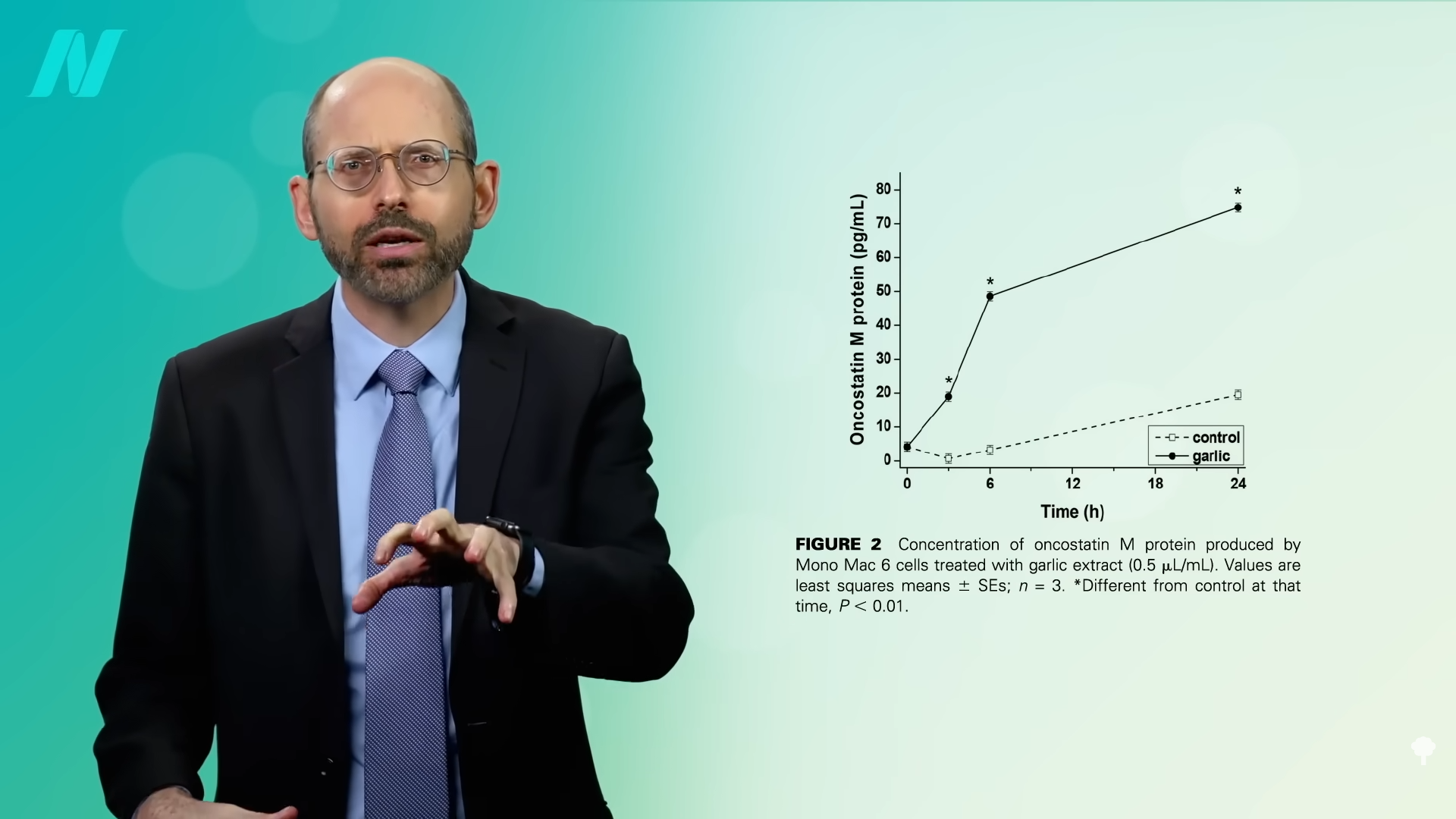

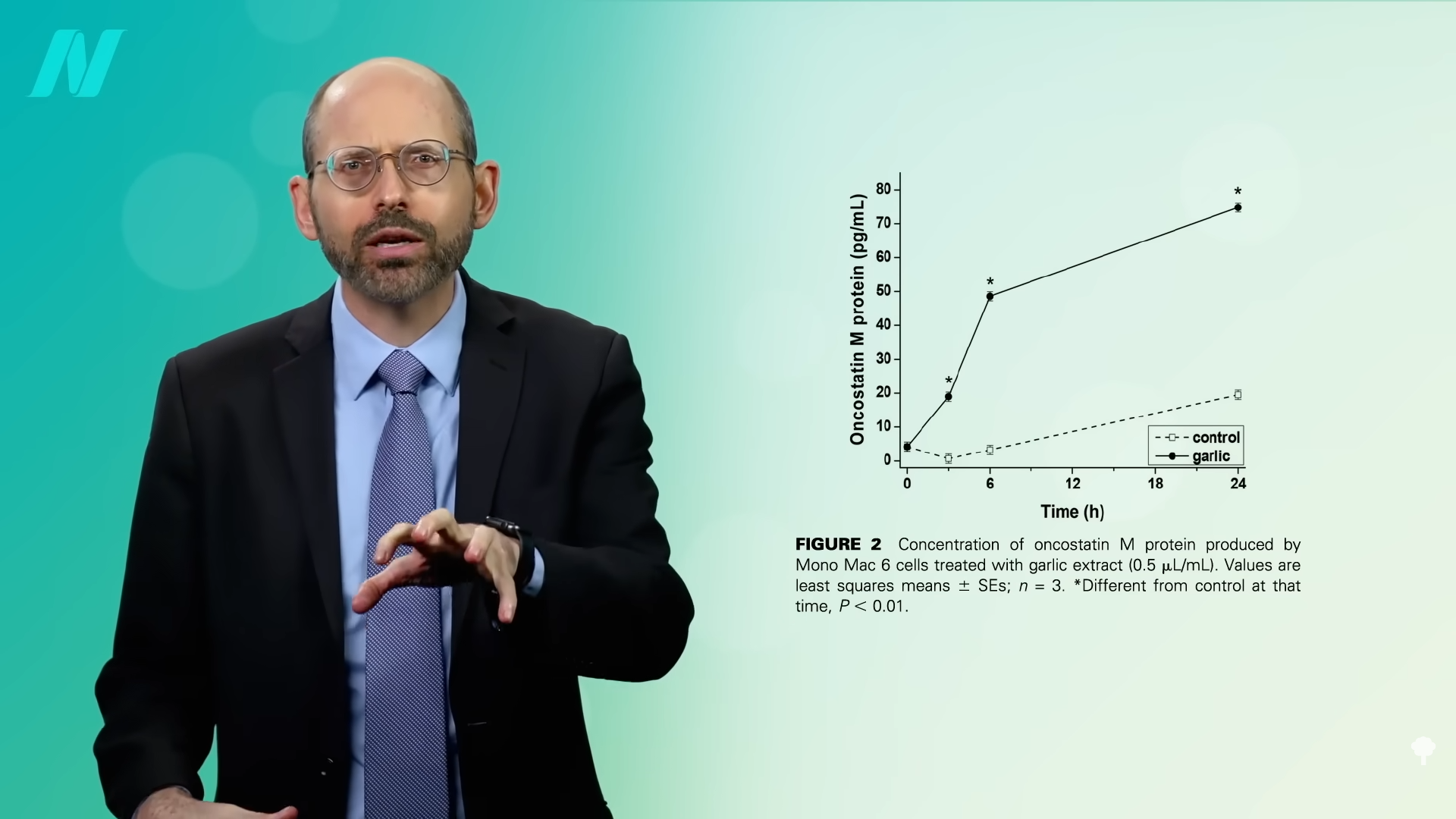

Researchers found that if you eat one big clove’s worth of crushed raw garlic, you get an alteration of the expression of your genes related to anti-cancer immunity within hours. You can see a big boost in the production of cancer-suppressing proteins like oncostatin when you drip garlic directly on cells in a petri dish, as shown in the graph below and at 2:25 in my video.

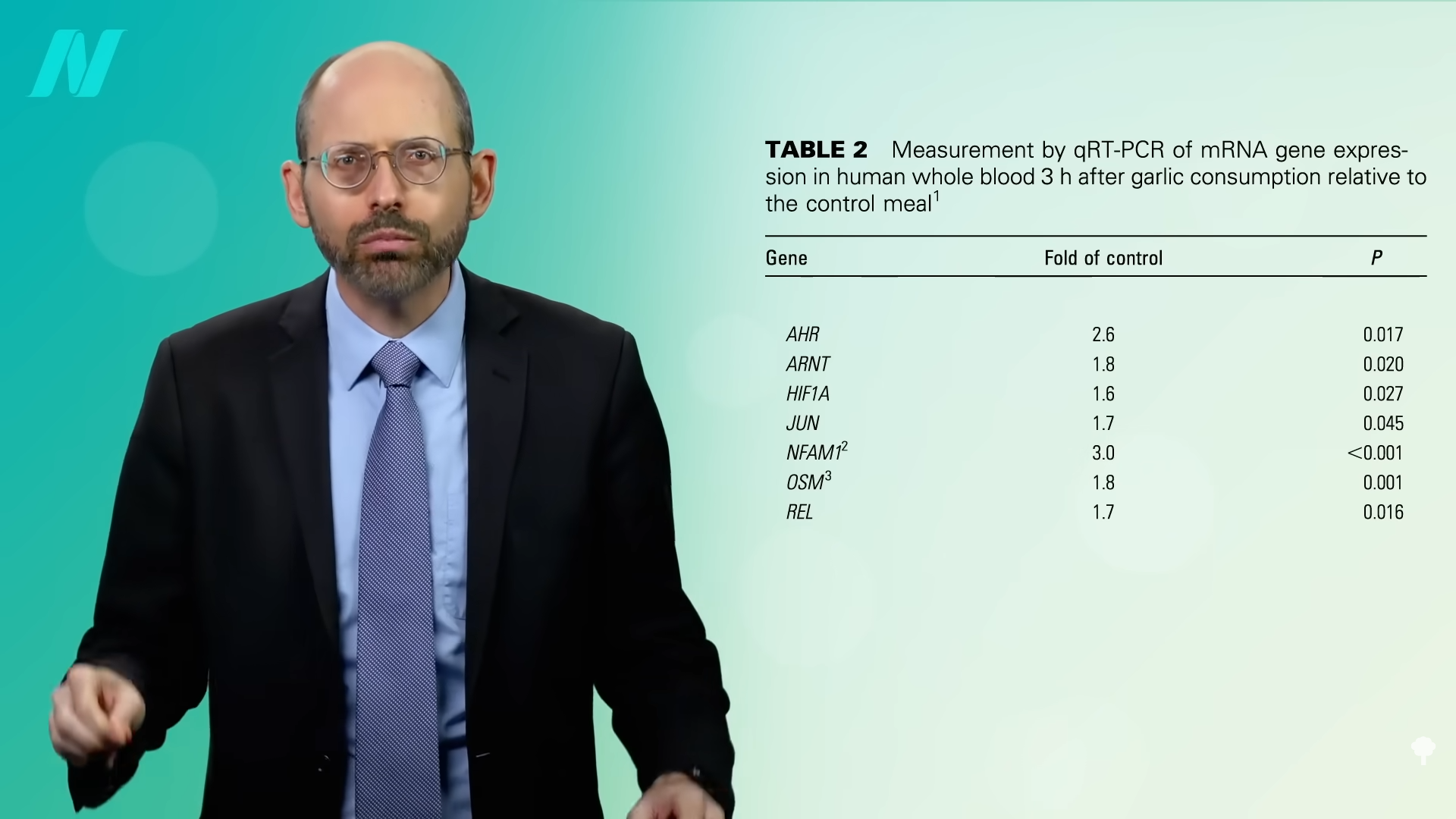

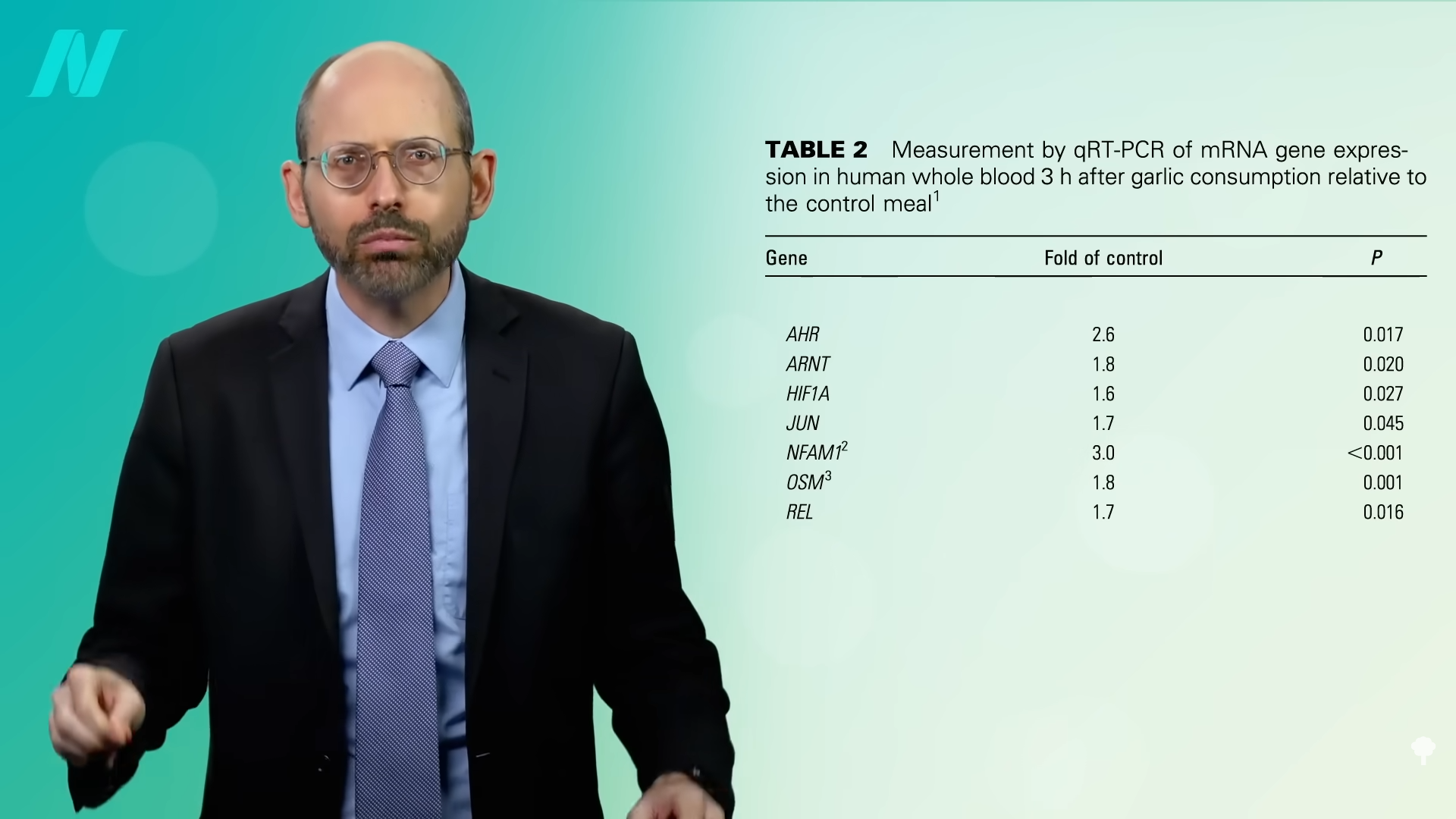

What’s more, you can also see boosted gene expression directly in your bloodstream within three hours of eating it, as seen below and at 2:34 in my video. Does this then translate into lower cancer risk?

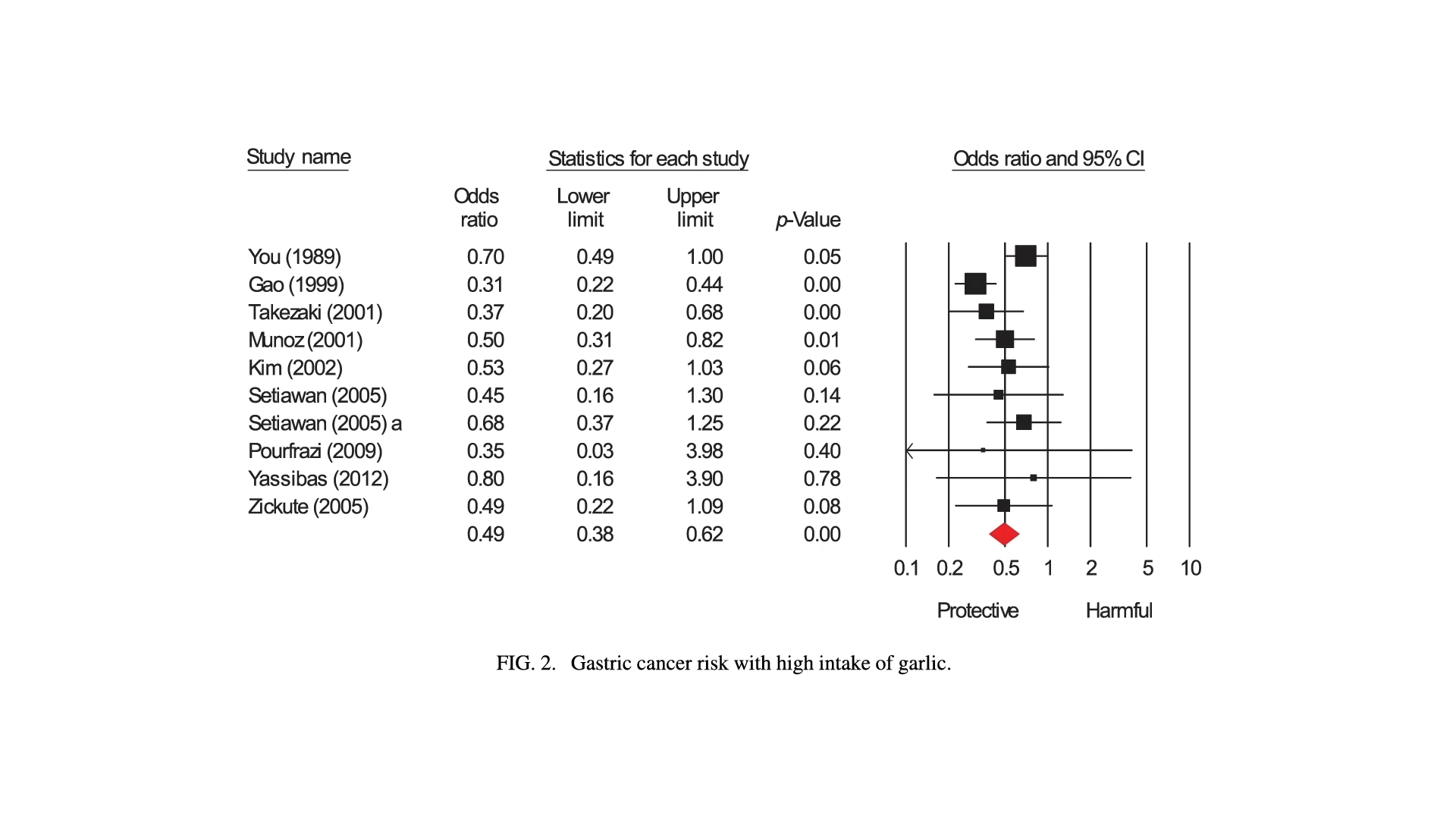

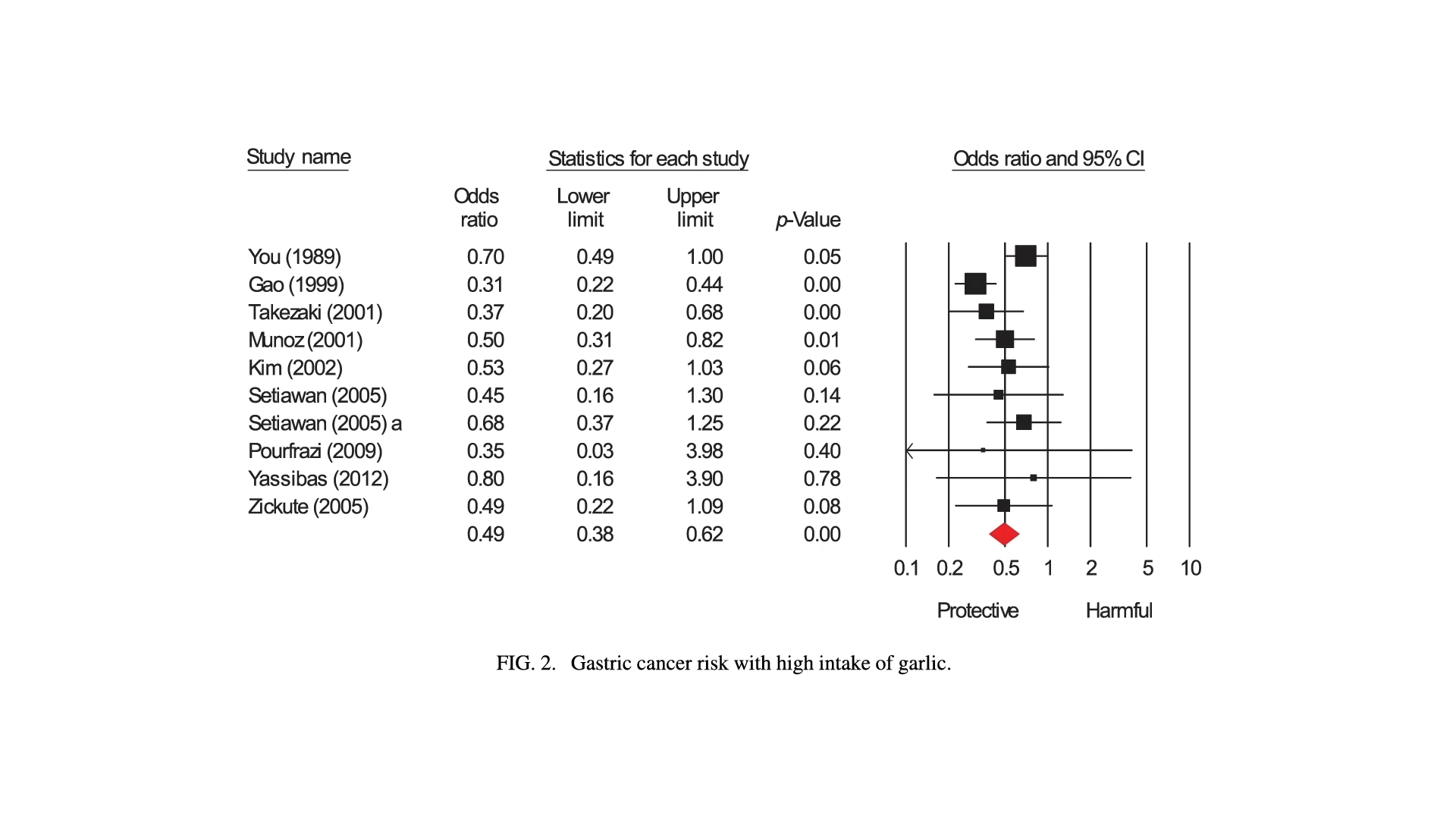

As you can see in the graph below and at 2:44 in my video, after putting together ten population studies, researchers found that those reporting higher consumption of garlic only had half the risk of stomach cancer.

How do you define “high” garlic consumption? Each study was different, from a few times a month to every day. Regardless, those who ate more garlic appeared to have lower cancer rates than those who ate less, suggesting a protective effect. Stomach cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related death around the world, and garlic “is relatively cheap; the product is freely available and easy to incorporate into a daily diet in a palatable manner”—and safely, too, so why not? And, perhaps, the more, the better.

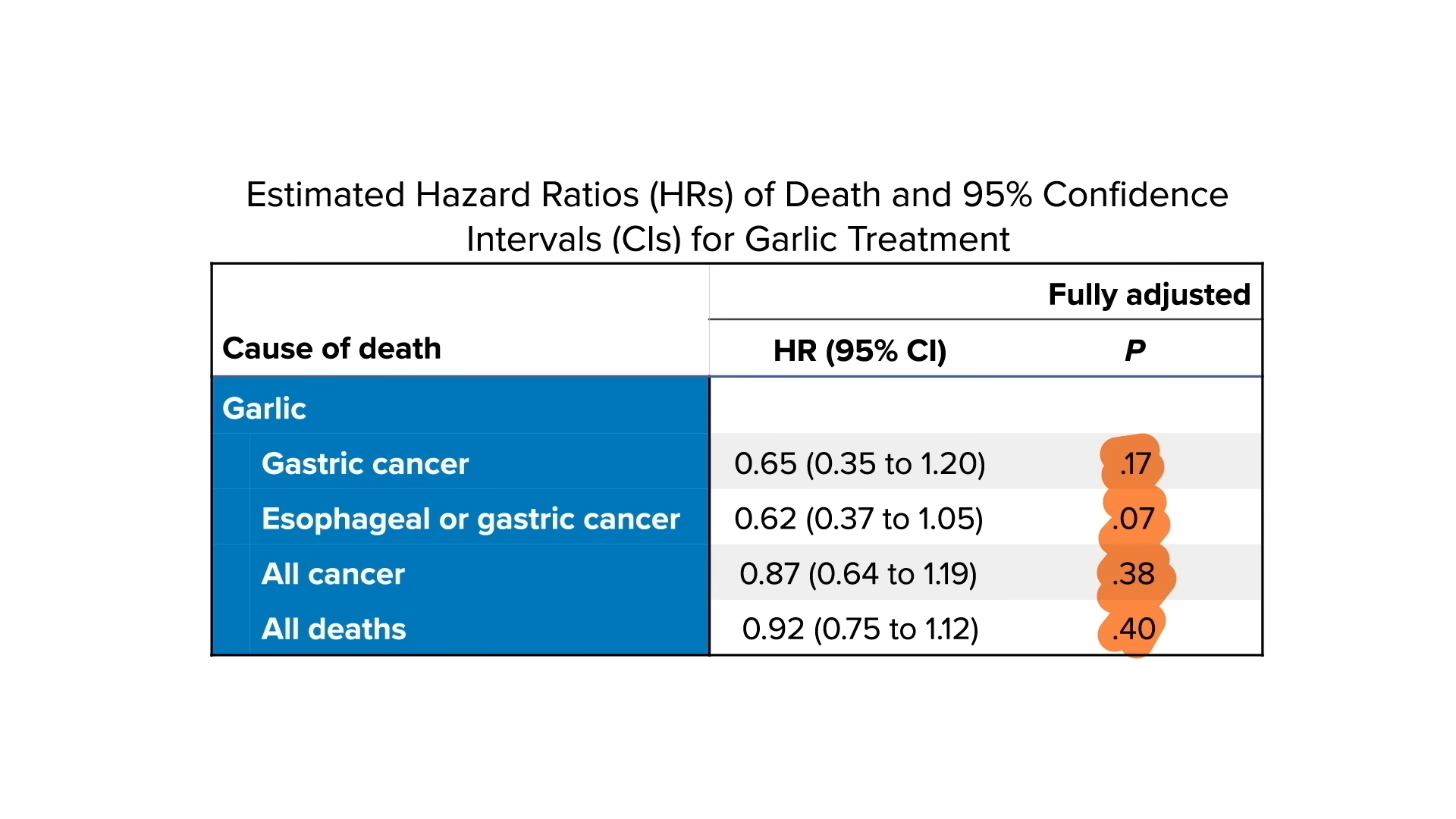

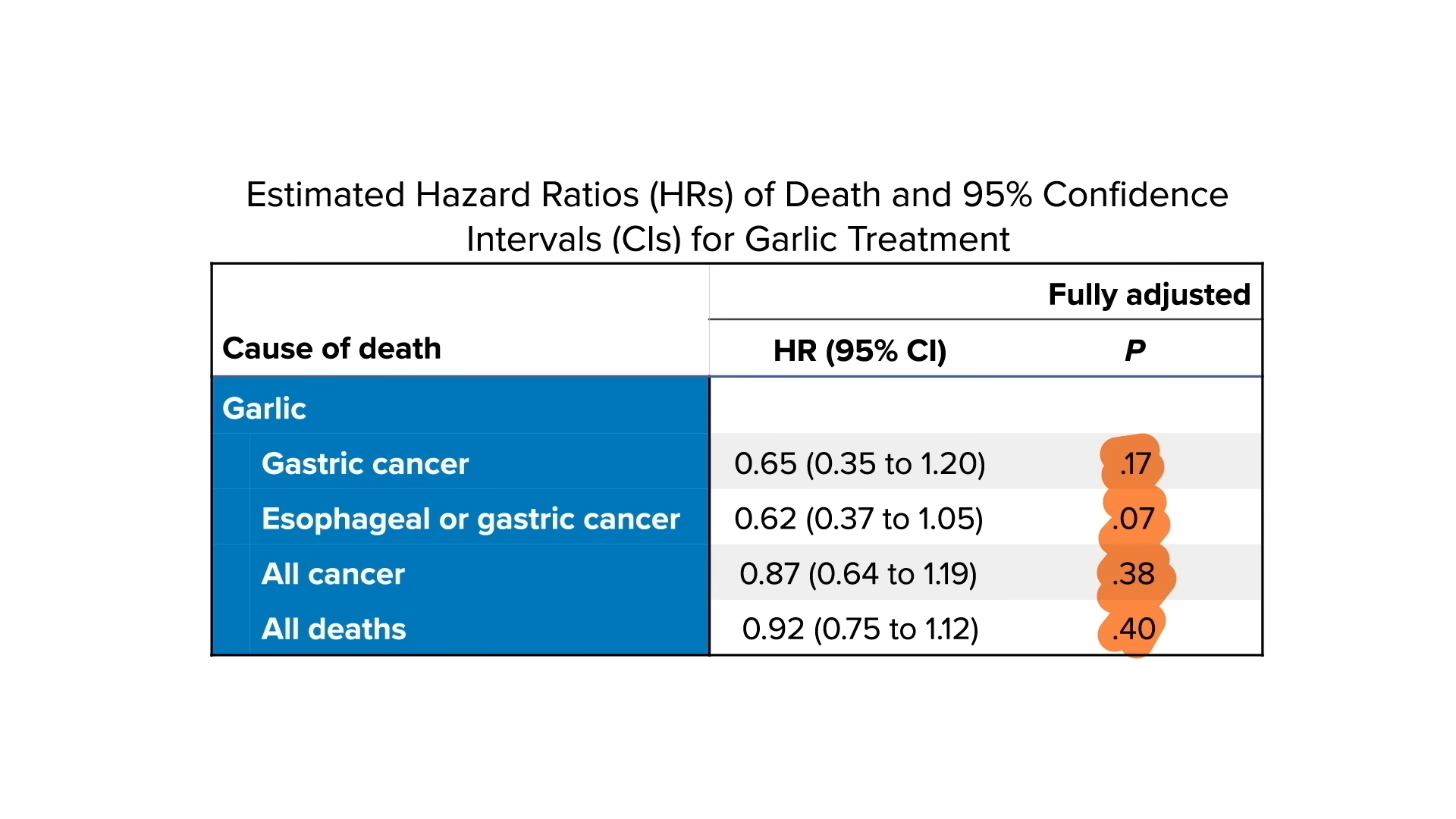

The only way to prove garlic can prevent cancer is to put it to the test. Thousands of individuals were randomized to receive seven years of a garlic supplement or a placebo. Those getting garlic did tend to get less cancer and die from less cancer, as you can see below and at 3:35 in my video, but the findings were not statistically significant, meaning that could have just happened by chance.

Why didn’t we see a more definitive result, given that garlic eaters appear to have much lower cancer rates? Well, the researchers didn’t give them garlic; they gave them garlic extract and oil pills. It’s possible that some of the purported active components weren’t preserved in supplement form. Indeed, one study of garlic supplements, for example, found that it might take up to 27 capsules to obtain the same amount of garlic goodness found in just half a clove of crushed raw garlic.

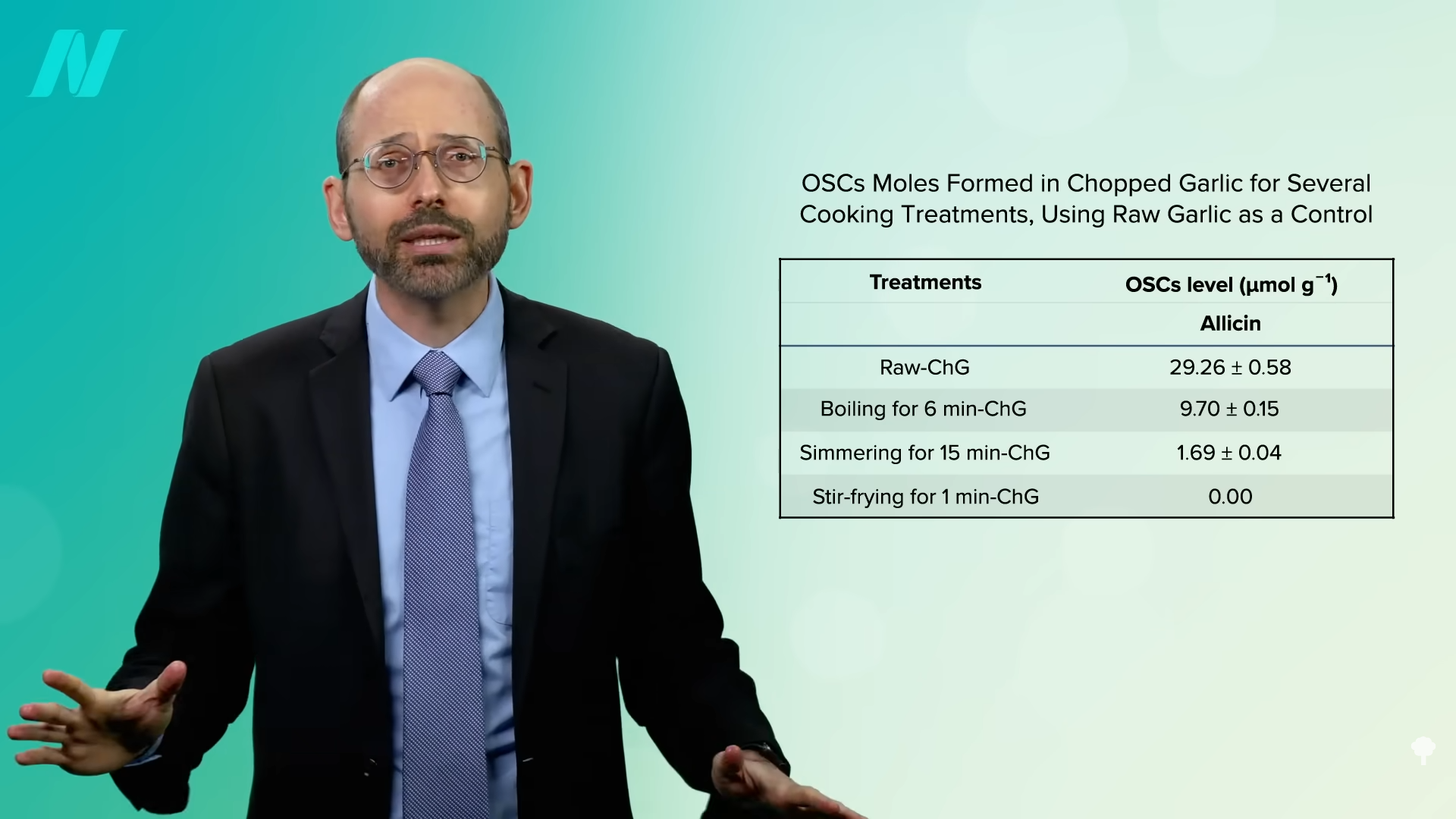

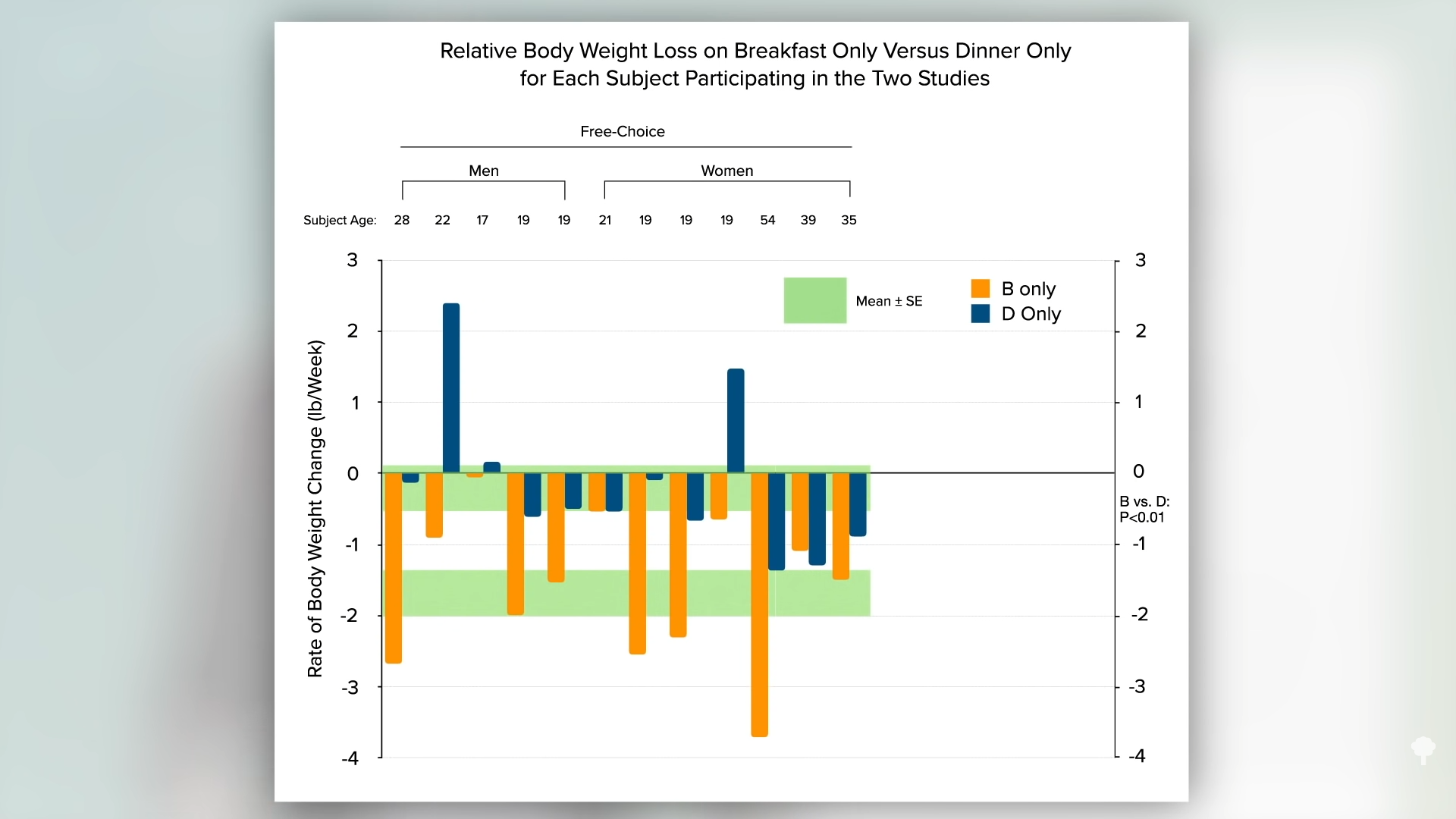

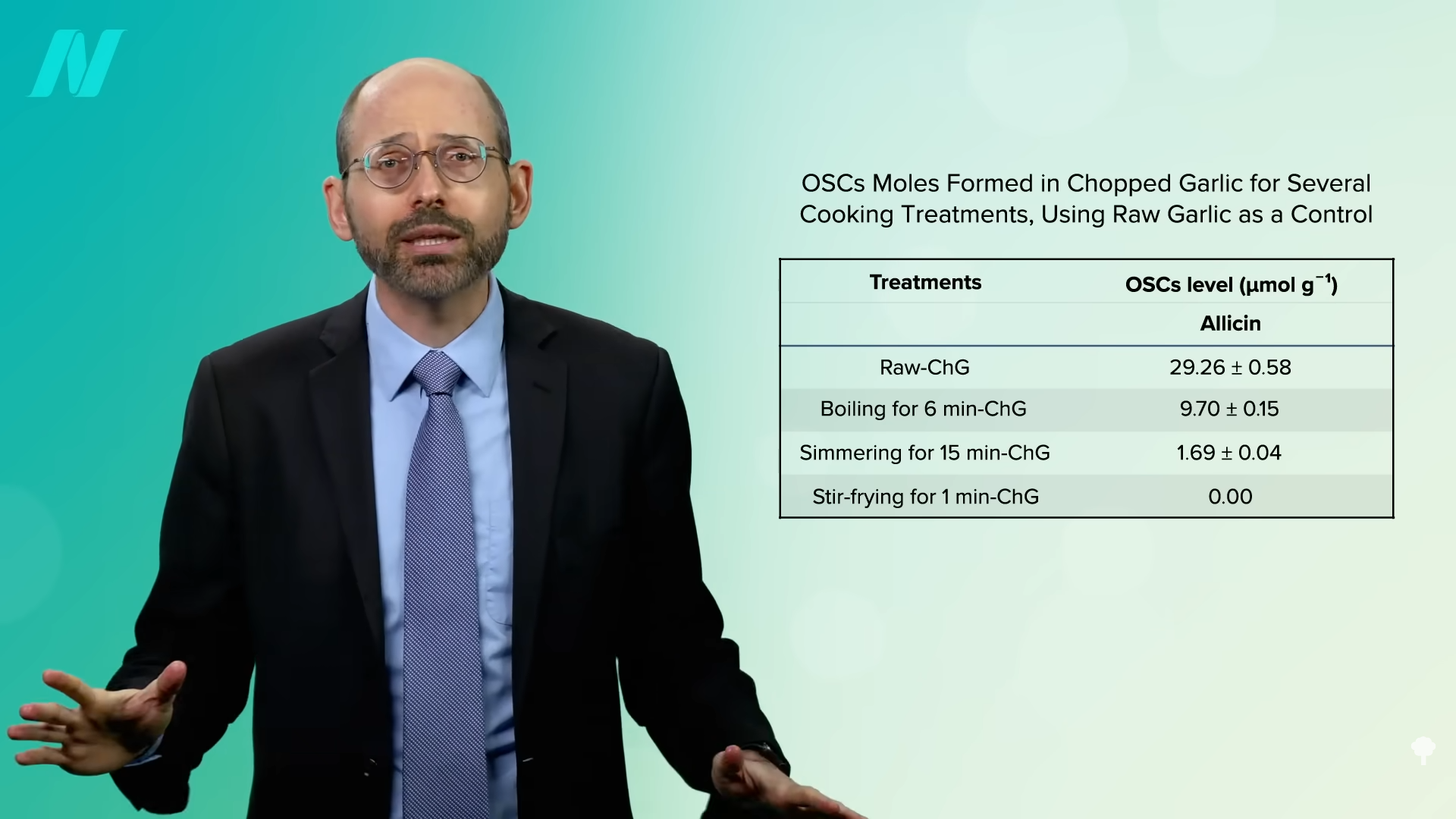

What happens if you cook garlic? If you compare raw chopped garlic to garlic simmered for 15 minutes, boiled for 6 minutes, or stir-fried for just 1 minute, you can get a three-fold drop in one of the purported active ingredients called allicin when you boil it, even more of a loss if you simmer it too long, and seemingly total elimination by even a single minute of stir-frying, as seen below and at 4:21 in my video. What about roasted garlic? Surprisingly, even though roasting is hotter than boiling, that cooking method preserved about twice as much. Raw garlic has the most, but it may be easier for some folks to eat two to three cloves of cooked garlic than even half a clove of raw.

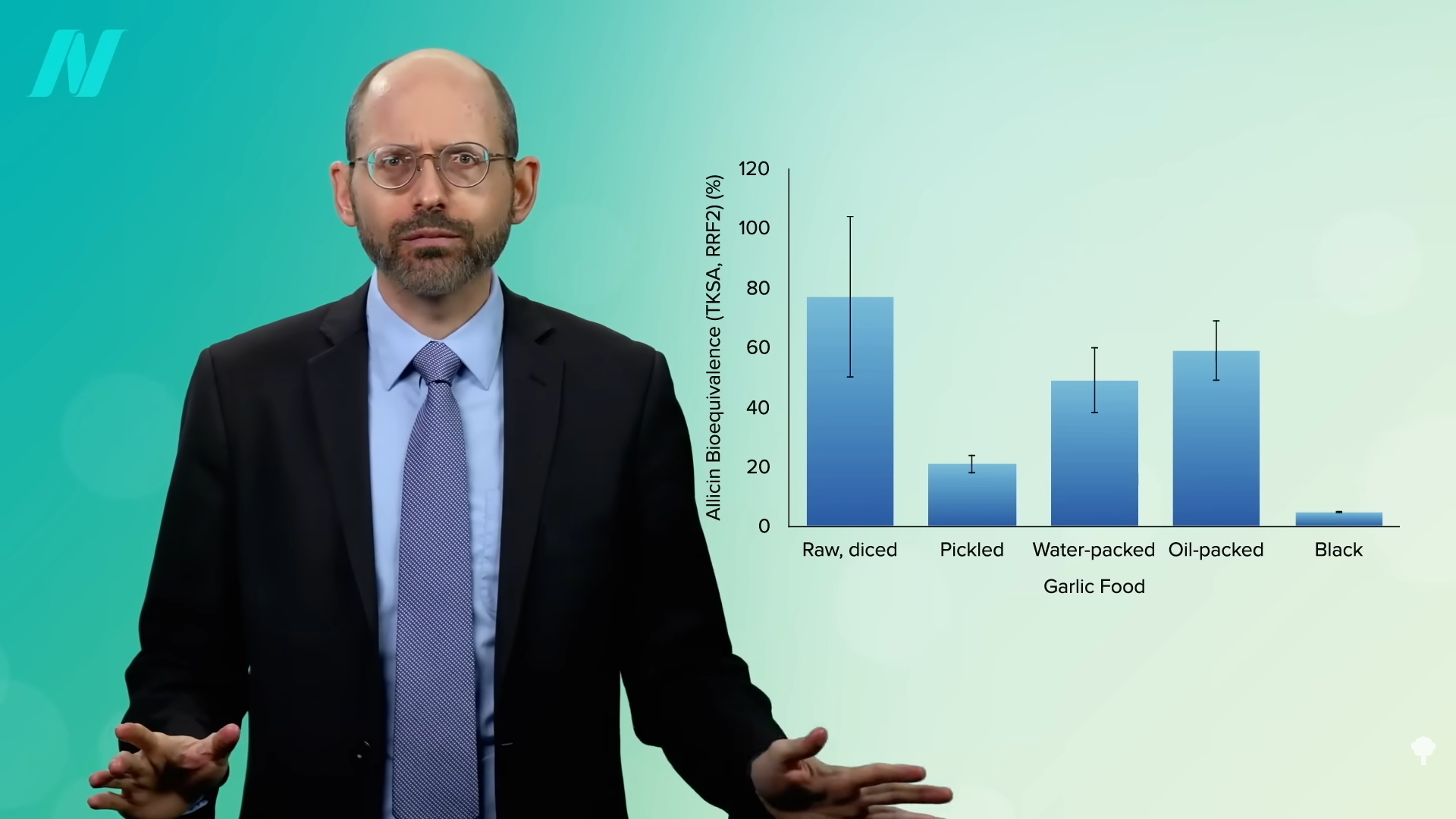

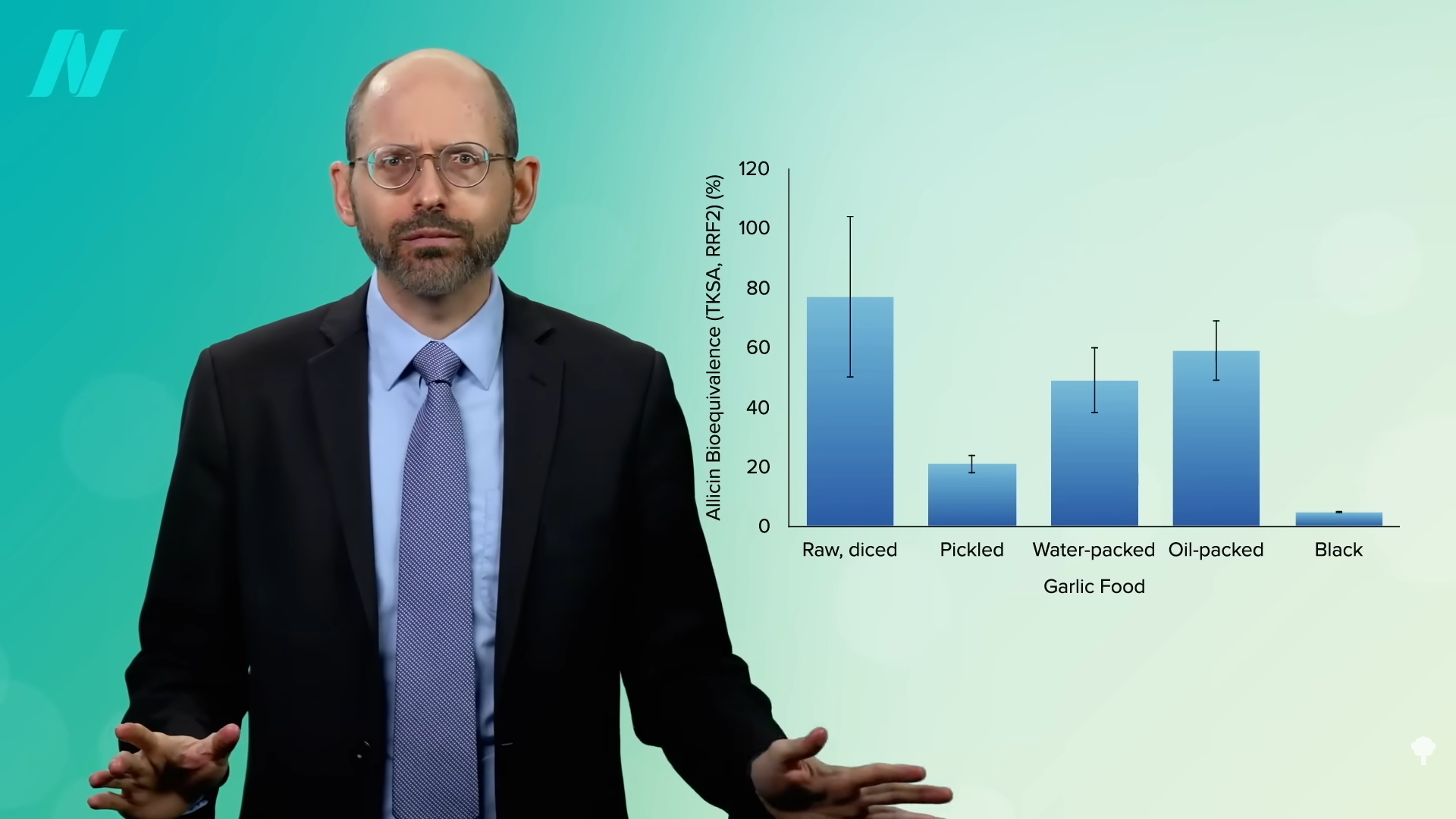

What about pickled garlic or those jars of minced garlic packed in water or oil? Fancy, fermented black garlic? Though jarred garlic may be more convenient, they have comparatively less garlicky goodness, especially pickled garlic, and the black garlic falls far behind, as you can see in the graph below and at 5:12 in my video.

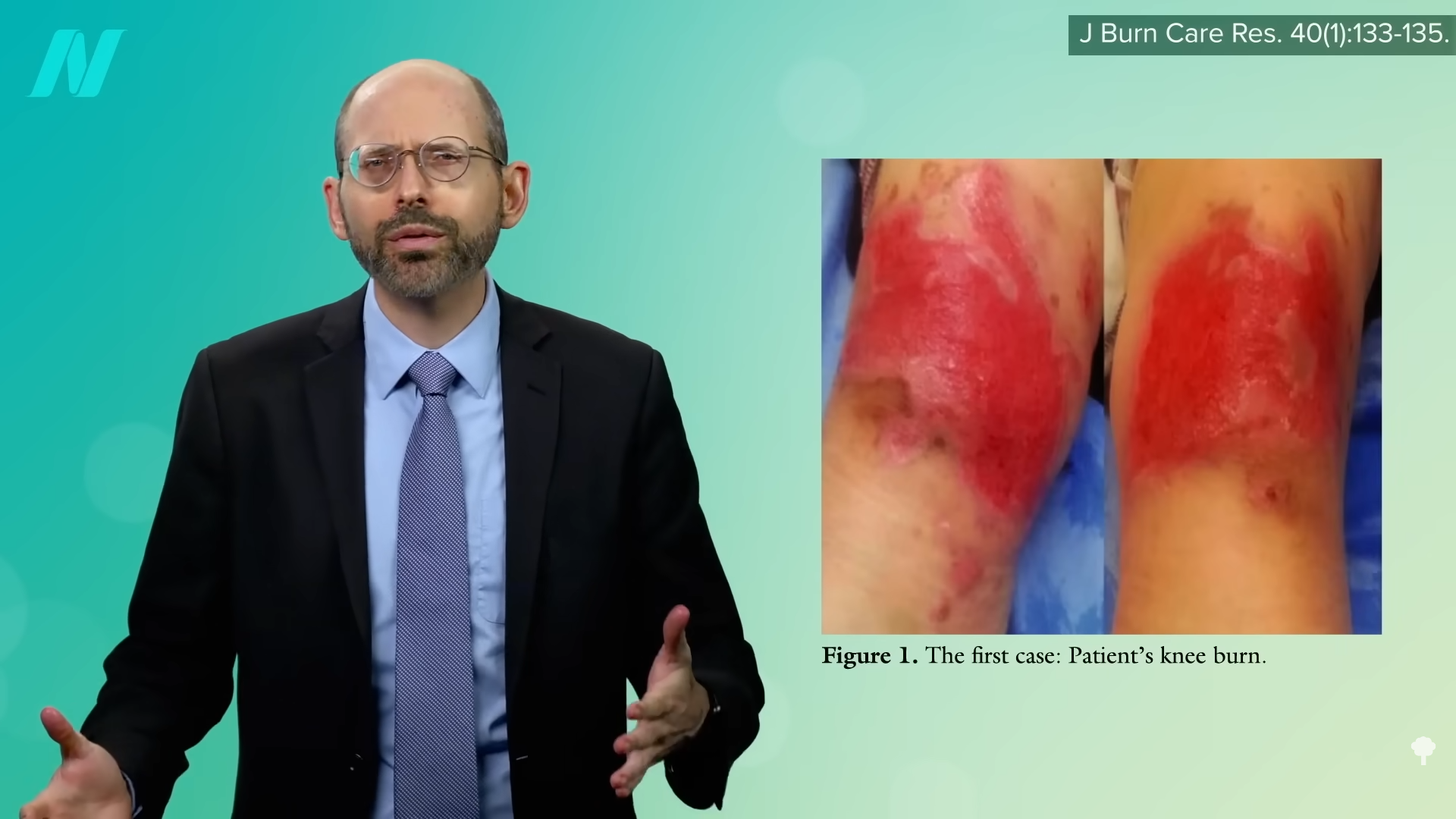

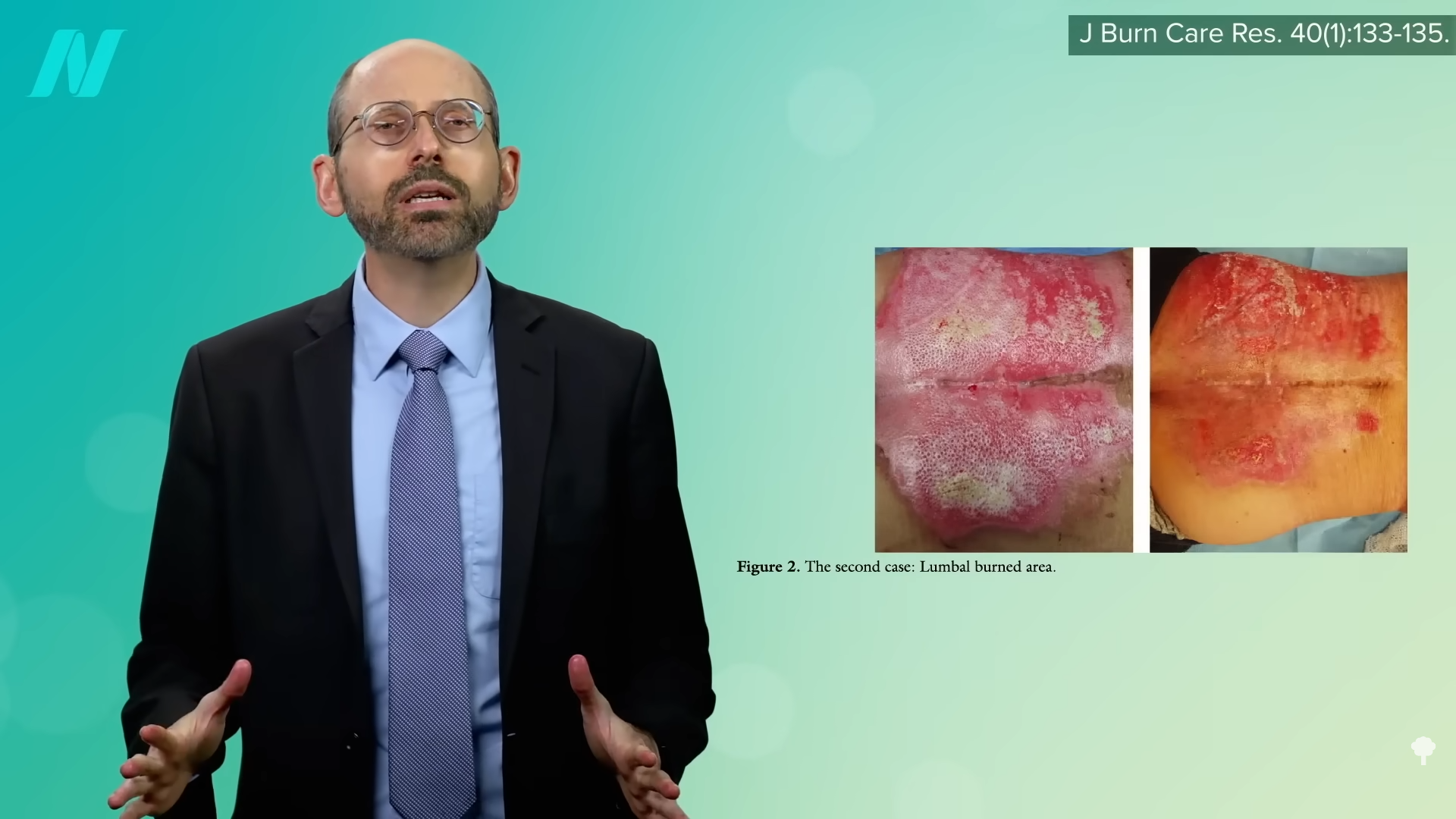

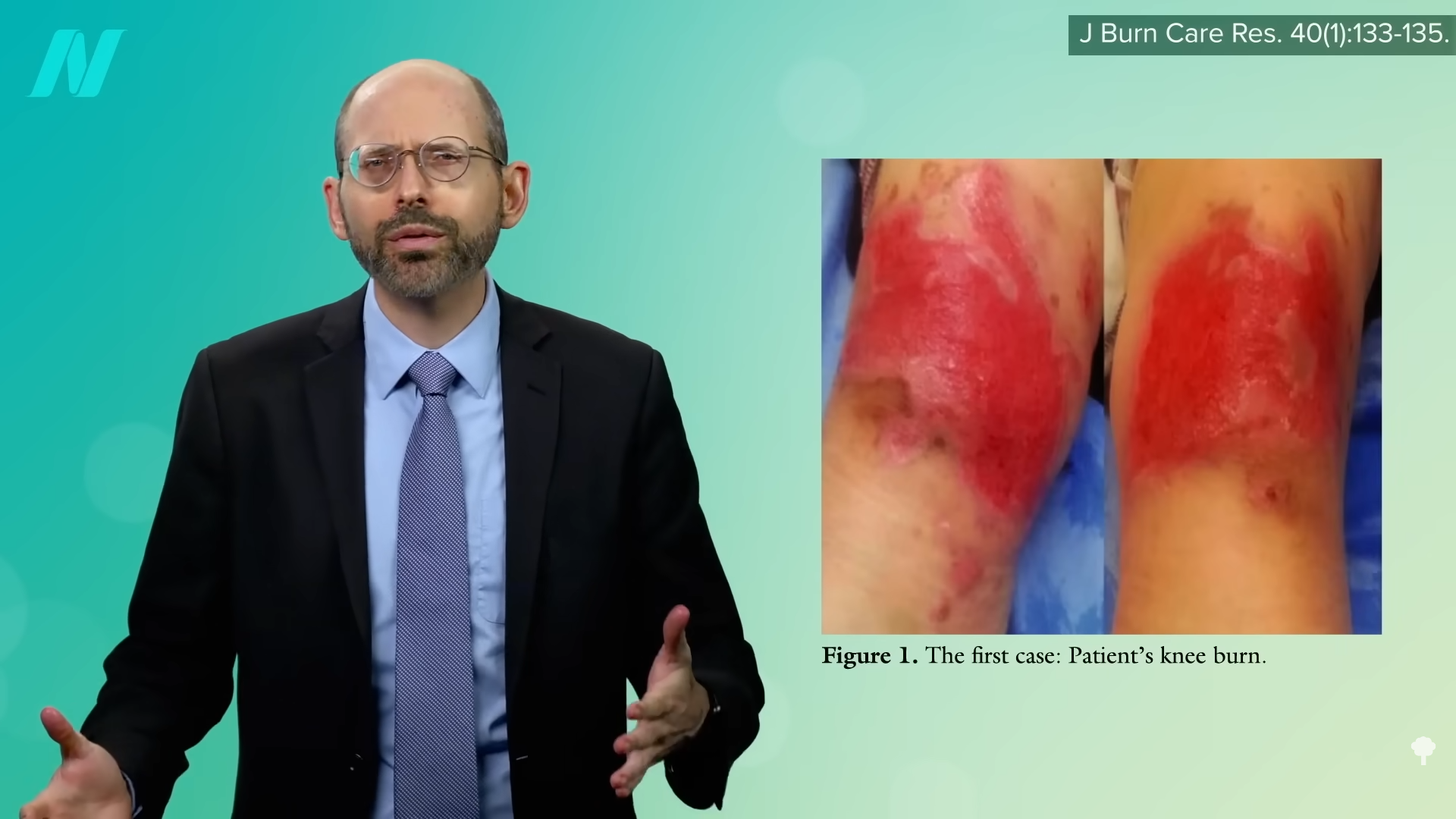

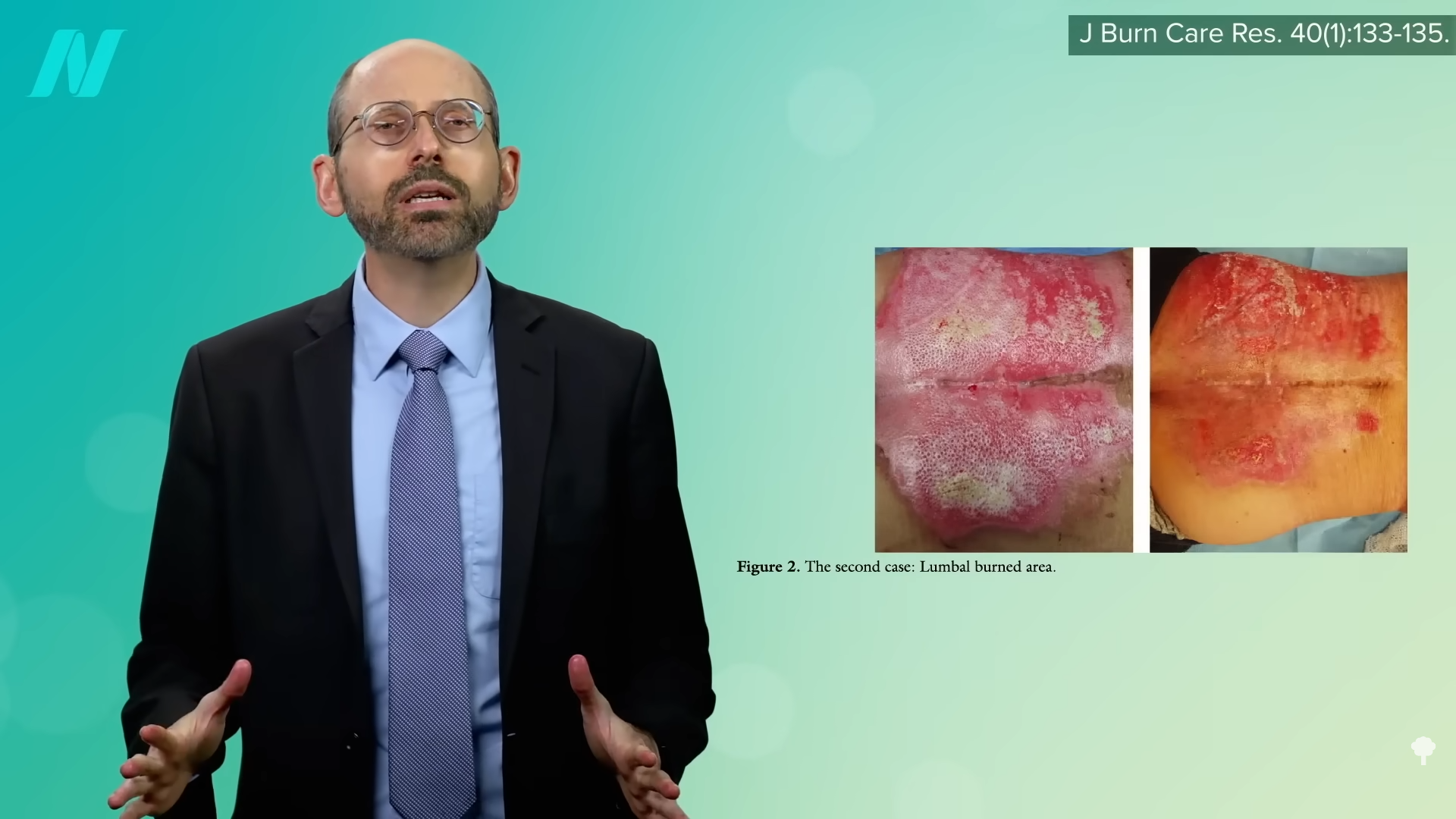

Can you eat too much? The garlic meta-analysis suggests there are no real safety concerns with side effects or overdosing, though that’s with internal use. You should not stick crushed garlic on your skin. It can cause irritation and, if left on long enough, can actually burn you. Wrap your knees with a garlic paste bandage or stick some on your back overnight, and you can end up burned, as seen below, and at 5:42 and 5:44 in my video.

Definitely don’t rub garlic on babies, even if you see an online article saying that topical garlic is good for respiratory disorders and your little one is congested. Below and at 5:57 in my video, you can see the blisters she got. The poor pumpkin! “It is crucial…to explain to patients that ‘natural’ does not equal ‘safe’…”

Don’t put it on your toes, don’t use it as a face mask, and don’t use it to try to get out of military service either.

If you just eat it like you’re supposed to, there shouldn’t be a problem. Some people can get an upset stomach if they eat too much, though, and you can’t really say there aren’t any side effects, given the “body odor and bad breath.”

The other video I mentioned is Friday Favorites: Benefits of Garlic Powder for Heart Disease. What else can garlic do? See related posts below.

And, for more on specific foods for fighting colds and cancer, check out related posts below.

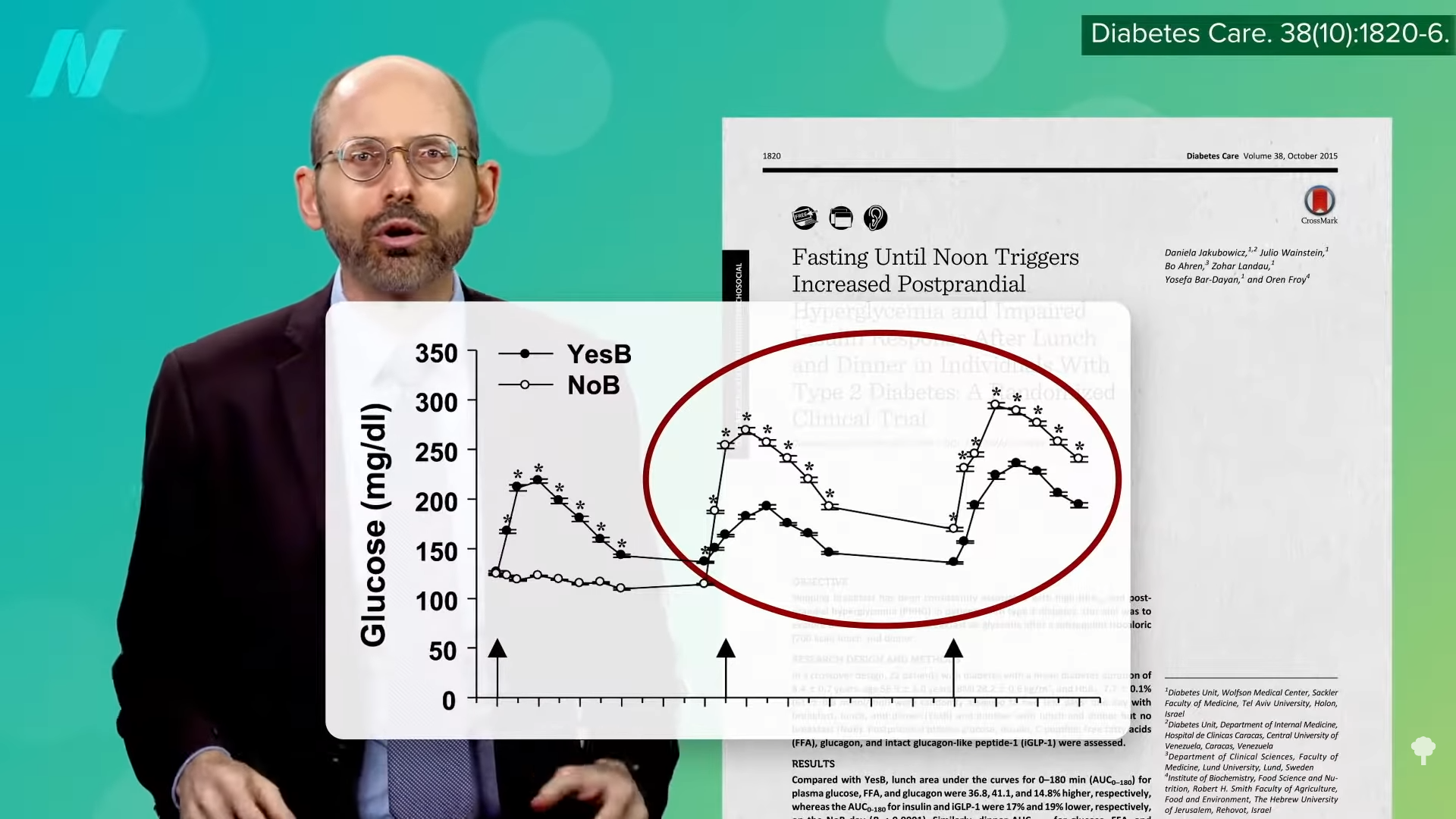

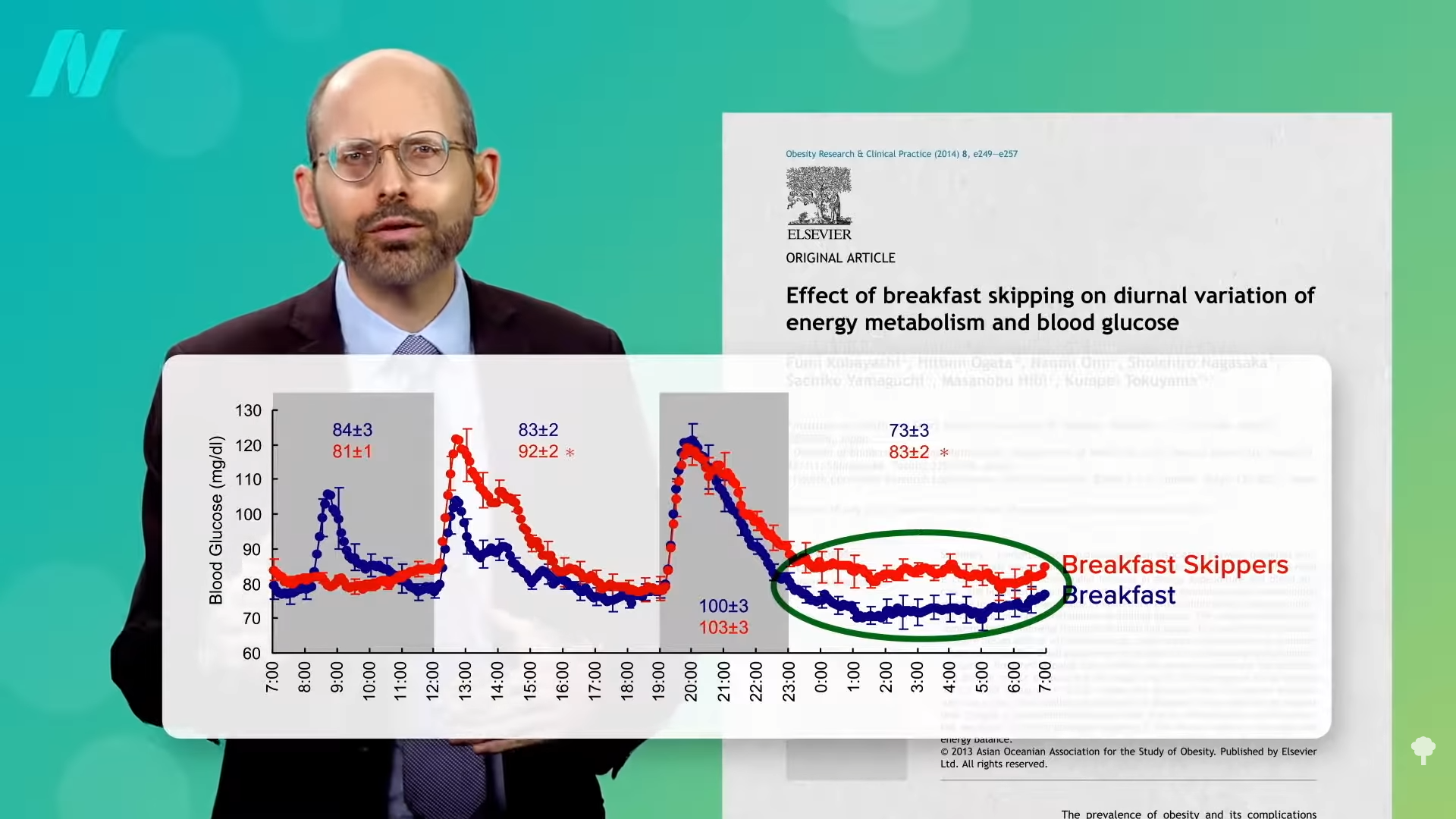

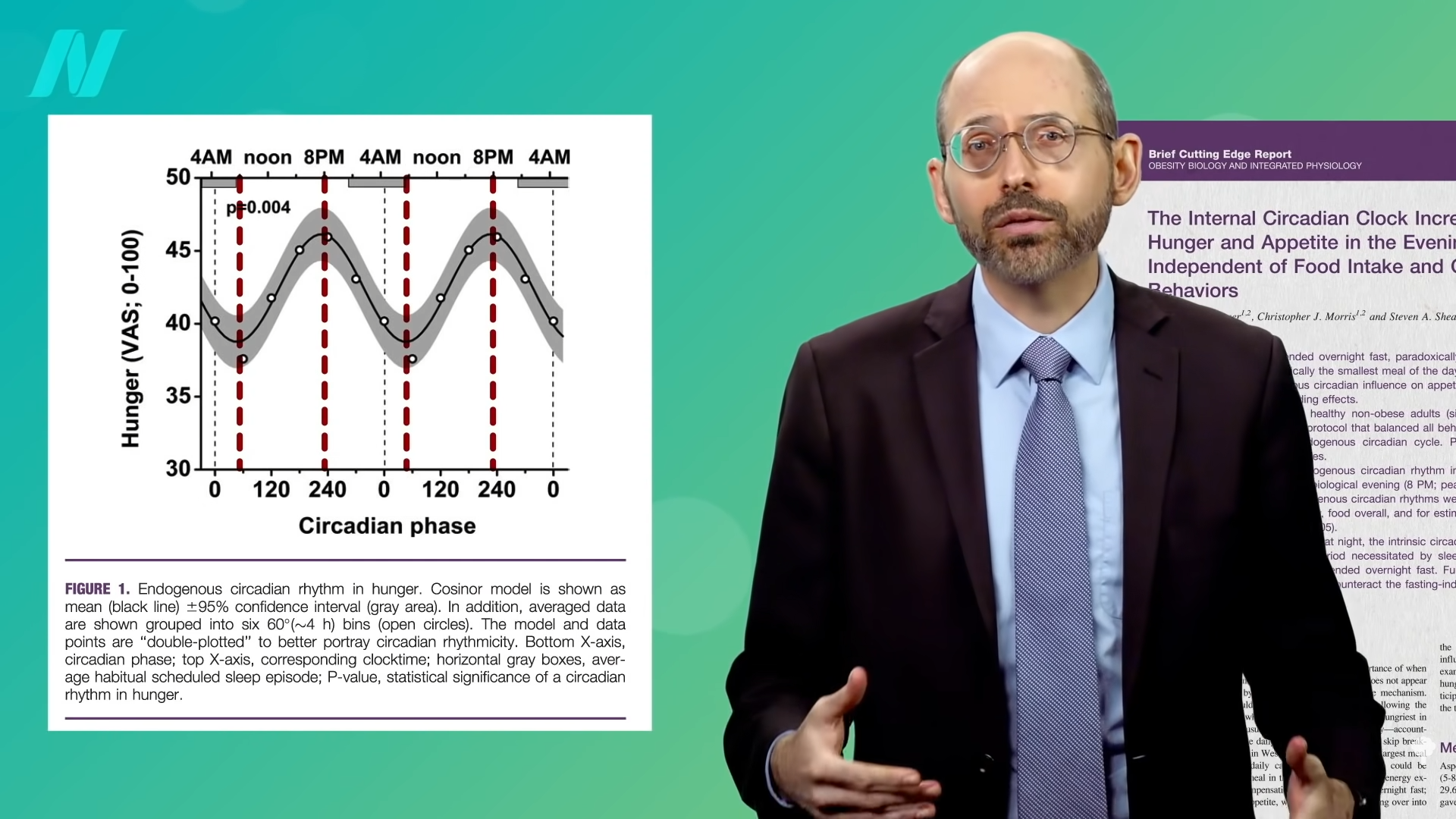

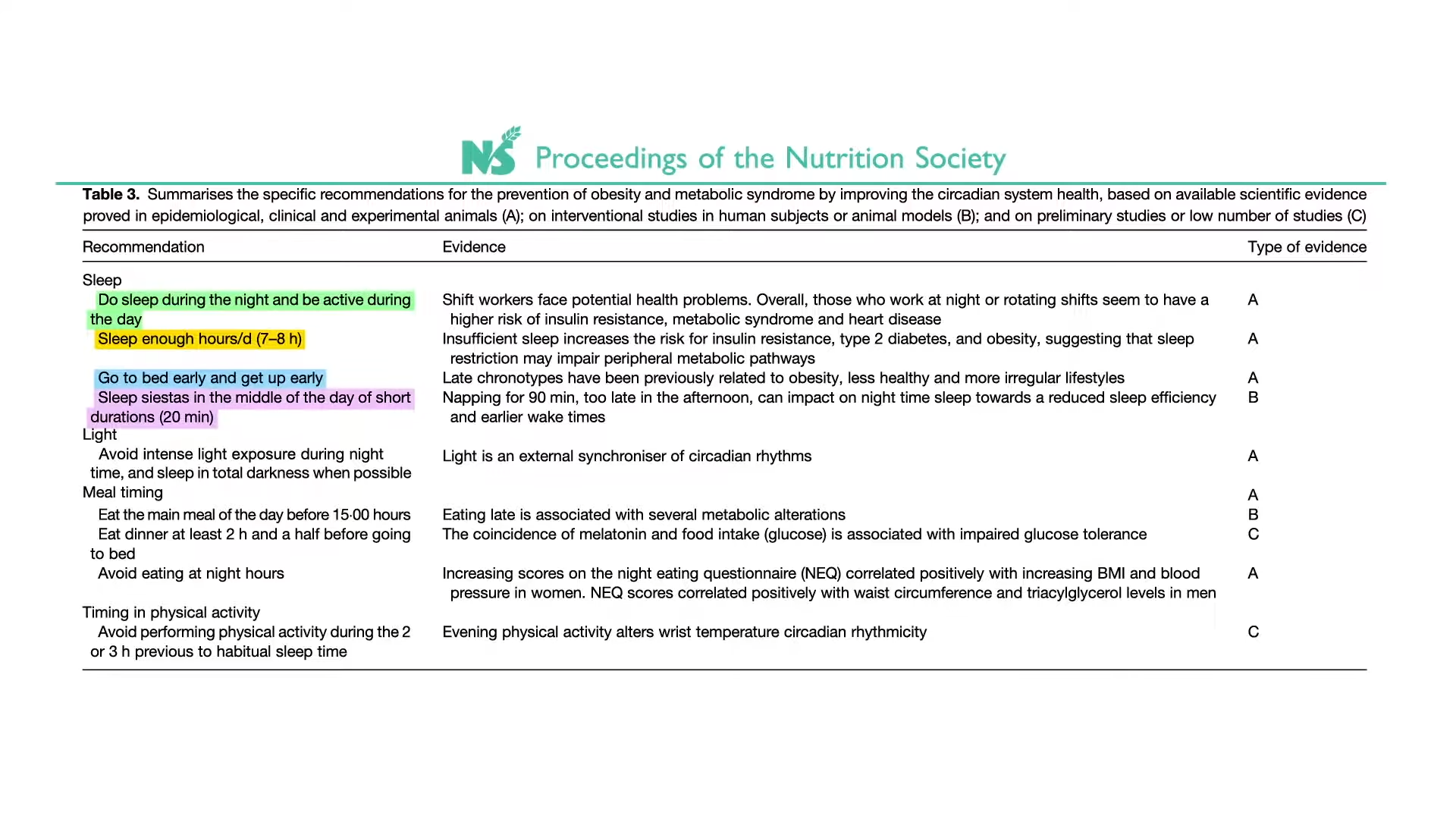

This was the last video in my chronobiology series. If you missed any of the others, check out the related posts below.

This was the last video in my chronobiology series. If you missed any of the others, check out the related posts below.