A smart scale does more than show your weight. It tracks metrics like body fat, muscle mass and water percentage, then syncs that data to your phone so you can see changes over time. If you want to take control of your health, the best smart scale gives you clear insights and helps you stay consistent with your goals.

Some models focus on accuracy, while others support multiple user profiles or connect with apps you already use. With so many options available, choosing the best smart scale comes down to the features that matter most for your routine. This guide highlights our top picks to make that decision easier.

Table of contents

Smart scale safety

There are valid reasons to weigh yourself but your self-worth shouldn’t be defined by what number shows up between your feet. If you’re looking to alter your body shape, that figure could go up as your waistline goes down since muscle weighs more than fat.

Some scales go further by providing additional metrics like visceral fat levels, giving you a more comprehensive picture of your health. Dr. Anne Swift, Director of Public Health teaching at the University of Cambridge, said “weighing yourself too often can result in [you] becoming fixated on small fluctuations day-to-day rather than the overall trend over time.” Swift added “it’s sometimes better to focus on how clothes fit, or how you feel, rather than your weight.”

A meta-analysis from 2016 found there may be some negative psychological impact from self weighing. A 2018 study, however, said there may be a positive correlation between regular weigh-ins and accelerated weight loss. It can be a minefield and I’d urge you to take real care of yourself and remember success won’t happen overnight.

Best smart scales for 2025

Display type: LCD | Wi-Fi connectivity: Yes | App connectivity: Yes | Length: 11.8 inches | Width: 11.8 inches | Number of profiles: Multiple

There are plenty of good budget scales out there, with Xiaomi and Fitbit offering very different products for very little money. Fitbit’s scale has far fewer features but has better build quality and is faster and more reliable than its even-cheaper rival. Crucially, it also leverages the Fitbit app, which is refined and easy-to-use, offering clean and easy to understand visualizations of your weight measurements.

Xiaomi, meanwhile, offers your weight and body composition data,but much of that is only seen inside the app. From a data perspective, Xiaomi has the edge but its companion app is terrible. The lag time for each weigh-in, too, leaves a lot to be desired with the Xiaomi, even if I had no qualms about its accuracy.

One of my nan’s favorite sayings was “you can either have a first class walk or a third class ride.” Fitbit’s scale is the very definition of a first class walk, polished, snappy with a great app but otherwise pretty limited. Xiaomi, meanwhile, charges less and offers more for your money but both the hardware and software lack any sort of polish. It’s up to you, but this is one of those rare occasions where I’d prefer the first class walk to the third class ride.

Pros

- Good build quality

- Easy to use

- Convenient integration with Fitbit app

Cons

- Fewer features than competitors

$50 at Amazon

eufy

Display type: LCD | Wi-Fi connectivity: Yes | App connectivity: Yes, syncs with Apple Health, Google Fit, or Fitbit | Length: 12.8 inches | Width: 12.8 inches | Number of profiles: Unlimited

This slot was previously occupied by Eufy’s last smart scale, the P2 Pro, so it’s little surprise its successor replaces it here. The company’s strategy remains the same: Throw as many features into the P3 smart scale as possible to ensure competitors are beaten on specs alone. It’s easy enough to use, and offers a whole host of data to better help you understand your body composition.

The P3 will measure your weight, body fat, muscle mass, heart rate, water, bone mass and your protein levels. It promises to calculate your basal metabolic rate, the number of calories you need to maintain a constant weight. There’s a gorgeous and clear-to-read color screen that lays out all your stats after you’ve weighed in, including trend graphs annotated with emojis.

A downside of this all-but-the-kitchen-sink approach is the lack of polish, cohesion and user friendliness. For instance, if multiple people in your home have similar weights, then you may need to tap the right quadrant of the scale to switch profile. That’s quite easy, or would be, if the selection window didn’t zoom by faster than the time it takes to lift your toes up and down.

It’s also a little unforgiving, nagging you at every weigh in with an orange angry emoji if you gain weight, even if the overall trend is positive. The inverse is also true — during testing, my kids somehow managed to get their joint weight registered under my name. But despite losing half of my body weight overnight, it did nothing but make my 3D avatar look gaunt.

If you’re prepared to accept the lack of polish to get ahold of the raw features, then Eufy’s latest scale is a solid option. You’re not likely to find anything that’s as similarly affordable and useful in this price range, especially given Eufy’s propensity for deep discounts.

Pros

- Easy to use

- A lot of data

- Very affordable

Cons

- Lackluster app

- Lack of polish and joined-up thinking

$100 at Amazon

Garmin

Display type: LCD | Wi-Fi connectivity: Yes | App connectivity: Yes | Length: 12.6 inches | Width: 12.2 inches | Number of profiles: 16

I’m partial to Garmin’s Index S2, but it’s the sort of scale that needs to be used by people who know what they’re doing. Everything about the hardware is spot-on, and the only fly in its ointment is the low refresh rate on its color screen. I can’t say how upsetting it is to see the screen refresh in such a laggy, unpolished manner, especially when you’re spending this much money. But that is my only complaint, with accurate and detailed readings, including your body water percentage. If you’re looking to set goals to alter your body shape, this isn’t the scale for you — it’s the scale you buy once you calculate your BMR on a daily basis.

Pros

- Good build quality

- Good integration with Garmin mobile app

- Provides a lot of data

$200 at Amazon

Withings

Display type: LCD | Wi-Fi connectivity: Yes | App connectivity: Yes, syncs with Apple Health and Google Fit | Length: 12.7 inches | Width: 12.7 inches | Number of profiles: 8

If you’re looking for a machine catering to your every whim, then Withings’ Body Comp is the way forward. It’s a luxury scale in every sense of the word, and you should appreciate the level of polish and technology on show here. Withings health app remains best in class, and I love how effortless the whole thing is to use on a daily basis. It’s a lot more expensive than the rest since it does so much more, like checking your nerve and arterial health. The retail price is a bit steep, but it’s one of those moments where you get exactly what you pay for.

Pros

- Good build quality

- Excellent software support with Withings app

- In-depth health tracking, including data on nerve and artery heatlh

Cons

- Runs on disposable batteries

$230 at Target

What to look for in a smart scale

Weight

A scale that measures weight is probably the top requirement, right? Whether you’re after a basic weight scale or a full-featured body fat scale, bear in mind, with all these measurements, the readings won’t be as accurate as a calibrated clinical scale. It’s better to focus on the overall trend, up or down over time, rather than a single measurement in isolation. Scales offering high-precision measurements can help, especially if you’re looking at the data to inform a specific health or fitness goal.

Connectivity

Before you buy your scale, work out how you’re planning on weighing yourself and when, as it is an issue. Some lower-end smart bathroom scales connect via Bluetooth and have no internal storage, so if you don’t have your phone to hand, it won’t record your weight. If your scale has Wi-Fi, then your scale can post the data to a server, letting you access them from any compatible device. Also, you should be mindful that some smart scales aren’t built with security in mind, so there’s a small risk to your privacy should your scale be compromised.

Bone density

The stronger your bones are, the less risk you have of breaks and osteoporosis — common concerns as you get older. Clinical bone density tests use low-power x-rays and some scales can offer you an at-home approximation. These bone mass tests pass a small electrical current through your feet, measuring the resistance as it completes its journey. The resistance offered by bones, fat and muscle are all different, letting your scale identify the difference. A body composition monitor often includes this feature, too, providing a detailed breakdown of bone density, fat and muscle mass.

Body fat percentage and muscle mass

Fat and muscle are necessary parts of our makeup, but too much of either can be problematic. Much like bone density, a body composition measurement feature can monitor your body fat and muscle mass percentages using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA). This measurement tests how well your body resists an electrical signal passing through your body. (It’s a rough rule of thumb you should have a 30/70 percent split between fat and muscle, but please consult a medical professional for figures specific to your own body and medical needs.) For those with specific athletic goals, smart scales offer an athlete mode to better tailor readings for accuracy. If body fat monitoring is a priority, look for a model marketed as a body fat scale.

BMI

A lot of scales offer a BMI calculation, and it’s easy to do since you just plot height and weight on a set graph line. Body Mass Index is, however, a problematic measurement that its critics say is both overly simplistic and often greatly misleading. Unfortunately, it’s also one of the most common clinical body metrics and medical professionals will use it to make judgements about your care.

Pulse Wave Velocity

French health-tech company Withings has offered Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV) on its flagship scale for some time, although regulatory concerns meant it was withdrawn for a period. It’s a measurement of arterial stiffness, which acts as a marker both of cardiovascular risk and other health conditions. For those looking for an even deeper understanding of their health, some scales now offer a body scan, which provides more advanced metrics such as segmental body composition and vascular health insights.

Wearables and integration

Pairing your smart scale with wearables like fitness trackers or smartwatches can further enhance your health-tracking ecosystem. Many smart scales sync directly with platforms like Fitbit or Apple Health, making it easier to track trends and analyze your data in one place.

Display

Less a specification and more a note: Smart bathroom scales have displays ranging from pre-printed LCDs or digital dot matrix layouts through to color display screens. On the high end, your scale display can show you trending charts for your weight and other vital statistics, and can even tell you the day’s weather. If you are short-sighted, and plan on weighing yourself first thing in the morning, before you’ve found your glasses or contacts, opt for a big, clear, high-contrast display.

App and subscriptions

You’ll spend most of your time looking at your health data through its companion scales app, and it’s vital you get a good one. This includes a clear, clean layout with powerful tools to visualize your progress and analyze your data to look for places you can improve. Given that you often don’t need to buy anything before trying the app, it’s worth testing one or two to see if you vibe with it. It’s also important you check app compatibility before making your purchase. Some health apps will only work with iOS or Android — not both. Apple Watch connectivity can also be a bonus for tracking workouts and health metrics seamlessly. Several companies also offer premium subscriptions, unlocking other features – including insights and coaching – to go along with your hardware.

Data portability

Using the same scale or app platform for years at a time means you’ll build up a massive trove of personal data. And it is (or should be), your right to take that data to another provider if you choose to move platforms in the future. Data portability is, however, a minefield, with different platforms offering wildly different options, making it easy (or hard) to go elsewhere.

All of the devices in this round-up will allow you to export your data to a .CSV file, which you can then do with as you wish. Importing this information is trickier, with Withings and Garmin allowing it, and Omron, Xiaomi, Eufy and Fitbit not making it that easy. (Apps that engage with Apple Health, meanwhile, can output all of your health data in a .XML file.)

Power

It’s not a huge issue but one worth bearing in mind that each scale will either run disposable batteries (most commonly 4xAAA) or with its own, built-in battery pack. Either choice adds an environmental and financial cost to your scale’s life — either with regular purchases of fresh cells or the potential for the whole unit to become waste when the battery pack fails.

How we tested and which smart scales we tested

For this guide, I tested six scales from major manufacturers:

Mi (Xiaomi) Body Composition Scale 2

Our cheapest model, Xiaomi / Mi’s Body Composition Scale 2 is as bare-bones as you can get, and it shows. It often takes a long while to lock on to get your body weight, and when it does you’ll have to delve into the Zepp Life-branded scales app in order to look at your extra data. But you can’t fault it for the basics, offering limited (but accurate) weight measurements and body composition for less than the price of a McDonald’s for four.

Fitbit, now part of Google, is the household name for fitness trackers and smartwatches in the US, right? If not, then it must be at least halfway synonymous with it. The Aria Air is the company’s stripped-to-the-bare bones scale, offering your weight and a few other health metrics, but you can trust that Fitbit got the basics right. Not to mention that most of the reason for buying a Fitbit product is to leverage its fitness app anyway.

Eufy’s Smart Scale P2 Pro has plenty of things to commend it – the price, the overall look and feel (it’s a snazzy piece of kit) and what it offers. It offers a whole host of in-depth functionality, including Body Fat, Muscle Mass, Water Weight, Body Fat Mass and Bone Mass measurements, as well as calculating things like your Heart Rate and Basal Metabolic Rate (the amount of calories you need to eat a day to not change weight at all) all from inside its app. In fact, buried beneath the friendly graphic, the scale offers a big pile of stats and data that should, I think, give you more than a little coaching on how to improve your overall health.

It’s worth noting that Anker – Eufy’s parent company – was identified as having misled users, and the media, about the security of its products a few years back. Its Eufy-branded security cameras, which the company says does not broadcast video outside of your local network, was found to be allowing third parties to access streams online. Consequently, while we have praised the Eufy Smart Scale for its own features, we cannot recommend it without a big caveat.

Given its role in making actual medical devices, you know what you’re getting with an Omron product. A solid, reliable, sturdy, strong (checks the dictionary for more synonyms) dependable piece of kit. There’s no romance or excitement on show, but you can trust that however joyless it may be, it’ll do the job in question and will be user-friendly. The hardware is limited, the app is limited, but it certainly (checks synonyms again) is steady.

Joking aside, Omron’s Connect app is as bare-bones as you can get, since it acts as an interface for so many of its products. Scroll over to the Weight page, and you’ll get your weight and BMI reading, and if you’ve set a fitness goal, you can see how far you’ve got to go to reach it. You can also switch to seeing a trend graph which, again, offers the most basic visualization of your workouts and progress.

Garmin’s got a pretty massive fitness ecosystem of its own, so if you’re already part of that world, its smart scale is a no-brainer. On one hand, the scale is one of the easiest to use, and most luxurious of the bunch, with its color screen and sleek design. I’m also a big fan of the wealth of data and different metrics the scale throws at you – you can see a full color graph charting your weight measurements and goal progress, and the various metrics it tracks in good detail. If there’s a downside, it’s that Garmin’s setup won’t hold your hand, since it’s for serious fitness people, not newbies.

At the highest end, Withings’ flagship Body Comp is luxurious, and luxuriously priced, a figure I’d consider to be “too much” to spend on a bathroom scale. For your money, however, you’ll get a fairly comprehensive rundown of body composition metrics including your weight, body fat percentage, vascular age, pulse wave velocity and electrodermal activity. Its monochrome dot matrix display may not be as swish as the Garmin’s, but it refreshes pretty quickly and feels very in-keeping with the hardware’s overall sleek look.

If you want to flaunt your cash, you don’t buy a car, you buy a supercar, or a hypercar if you’re flush enough. What then, do we call Withings’ $400 Body Scan if not a super-smart scale, or a hyper-smart scale? As well as doing everything the Body Comp does, plus running a six-lead ECG, segmented body composition, and will even check for neuropathy in your feet. It is the best scale I’ve ever used, it is also the most expensive, and I suspect it’s too much device for almost everyone who’d consider buying one.

Smart scales FAQs

What’s the difference between a smart scale and a regular scale?

A regular scale is pretty straightforward — it tells you how much you weigh, and that’s usually it. A smart scale, on the other hand, does much more. Not only does it give you your weight measurements, but it can also track things like your body fat percentage, muscle mass, and even your BMI. Some smart scales even monitor more advanced metrics like bone density, depending on the model.

What’s even better is that smart scales sync with scales apps on your phone using Wi-Fi or Bluetooth, so you can see all your health data in one place. This lets you monitor trends over time, like if your muscle mass is increasing or your body fat percentage decreasing.

How do smart scales work with more than one person using it?

When more than one person in a household uses the smart scale, it usually recognizes each person by their weight range and other body measurements (like body fat percentage). Most smart scales allow you to set up individual profiles in the companion app, and once your profile is linked, the scale can automatically figure out who’s standing on it.

Let’s say you and a family member have fairly different weights — the scale will easily know who’s who based on that. But if you and someone else have similar weights, it might ask you to confirm the profile on your phone after the weigh-in. Some scales even let you assign a profile manually in the scales app if it’s not sure.

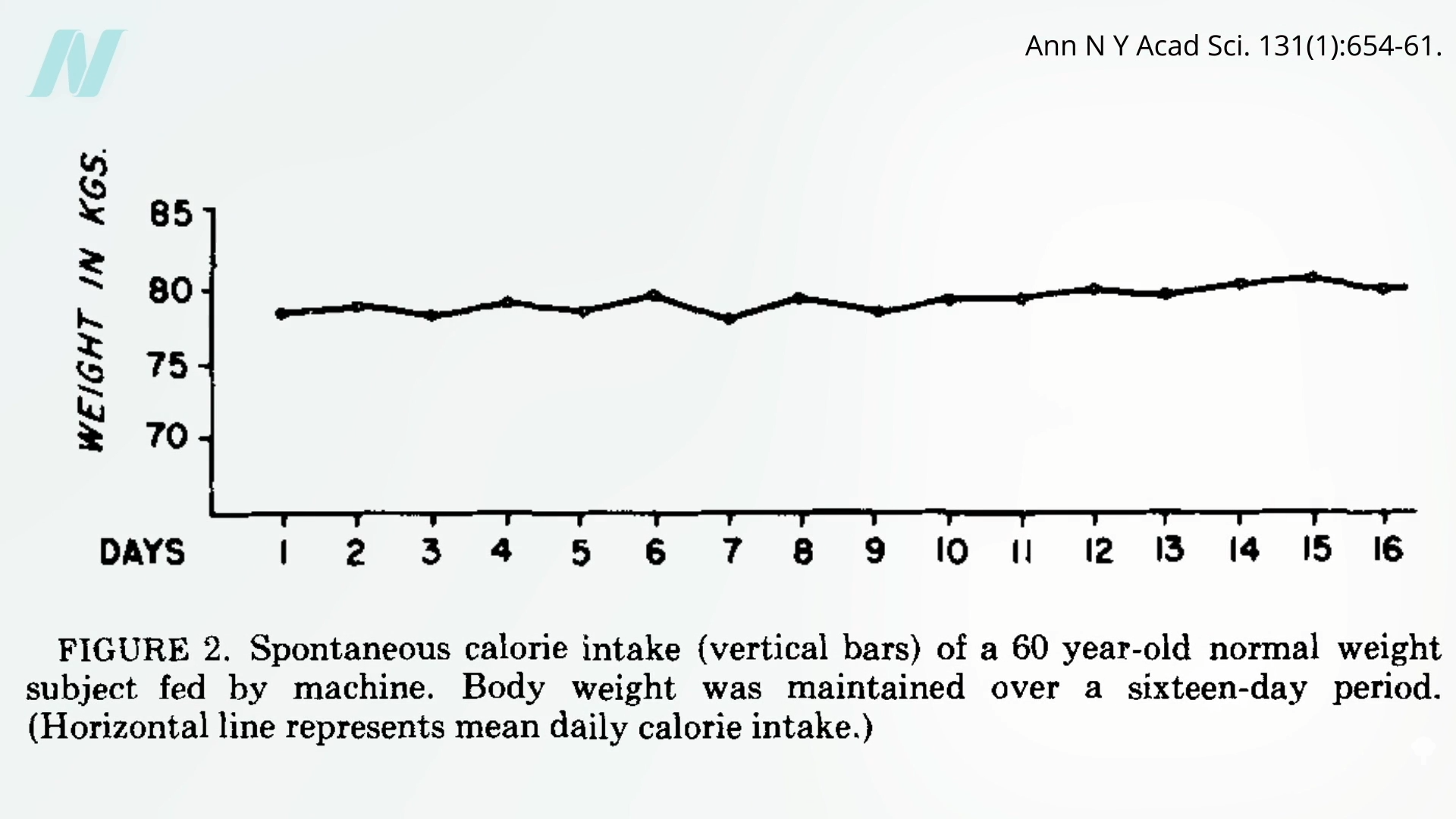

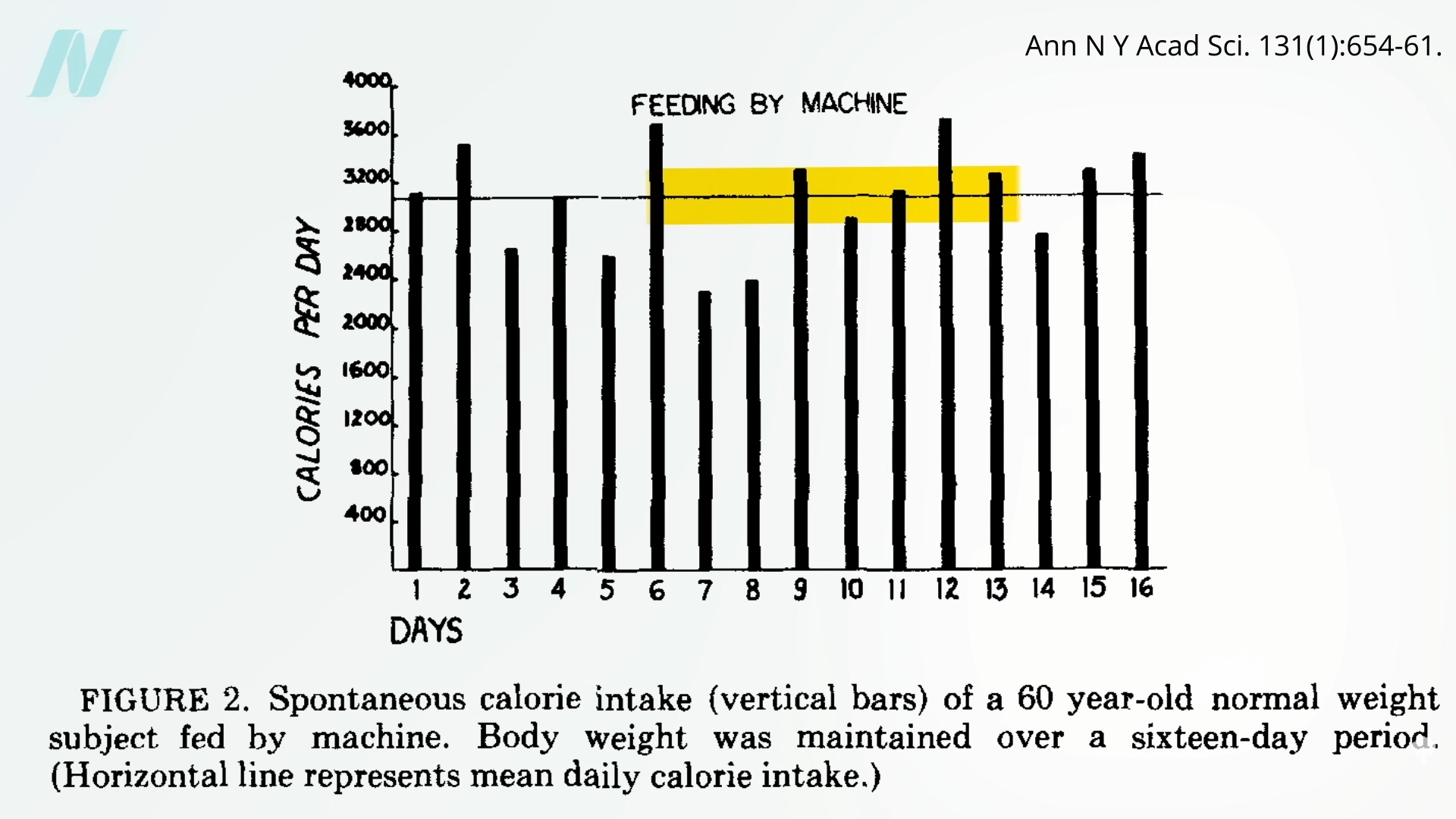

We appear to

We appear to

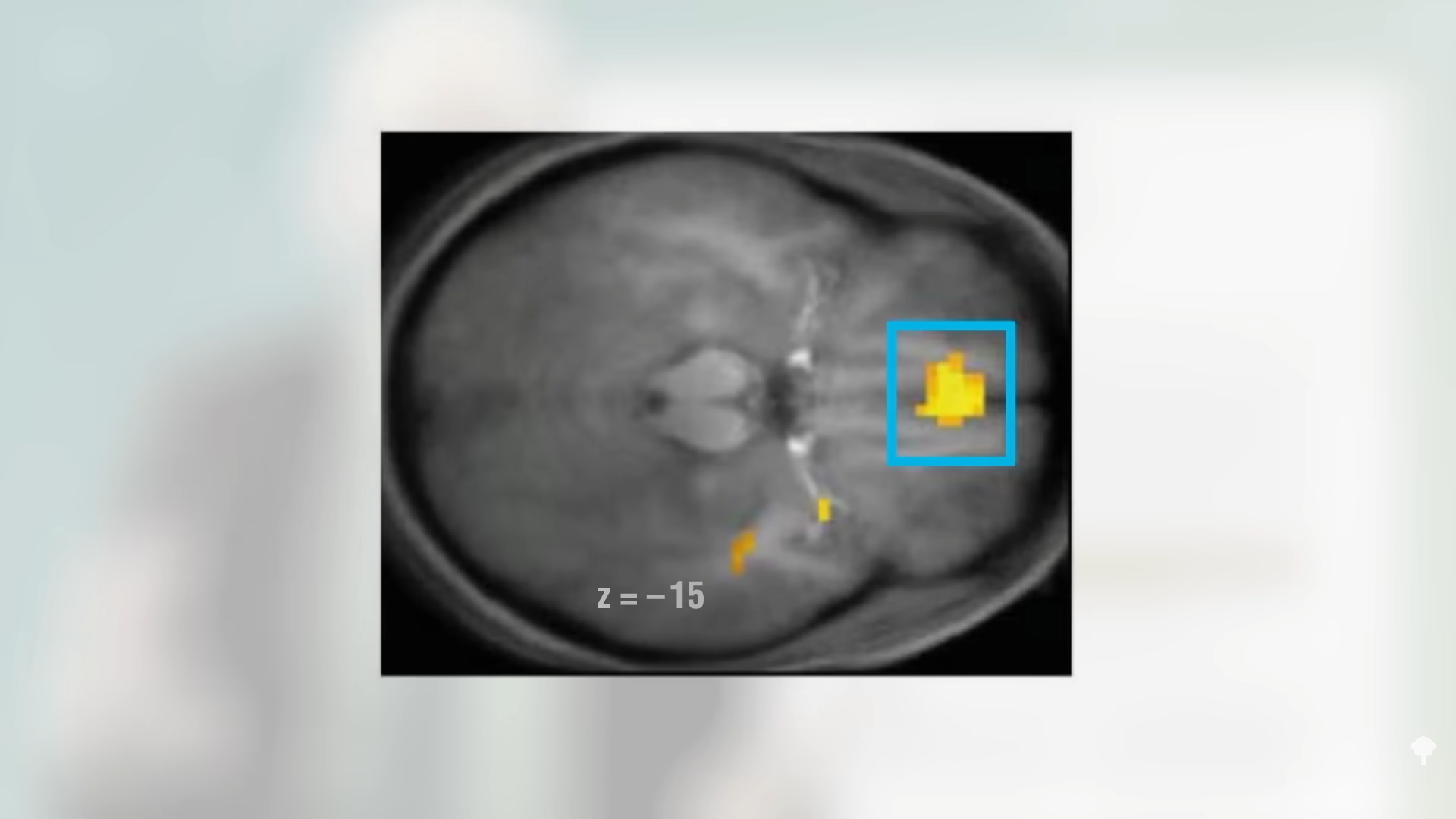

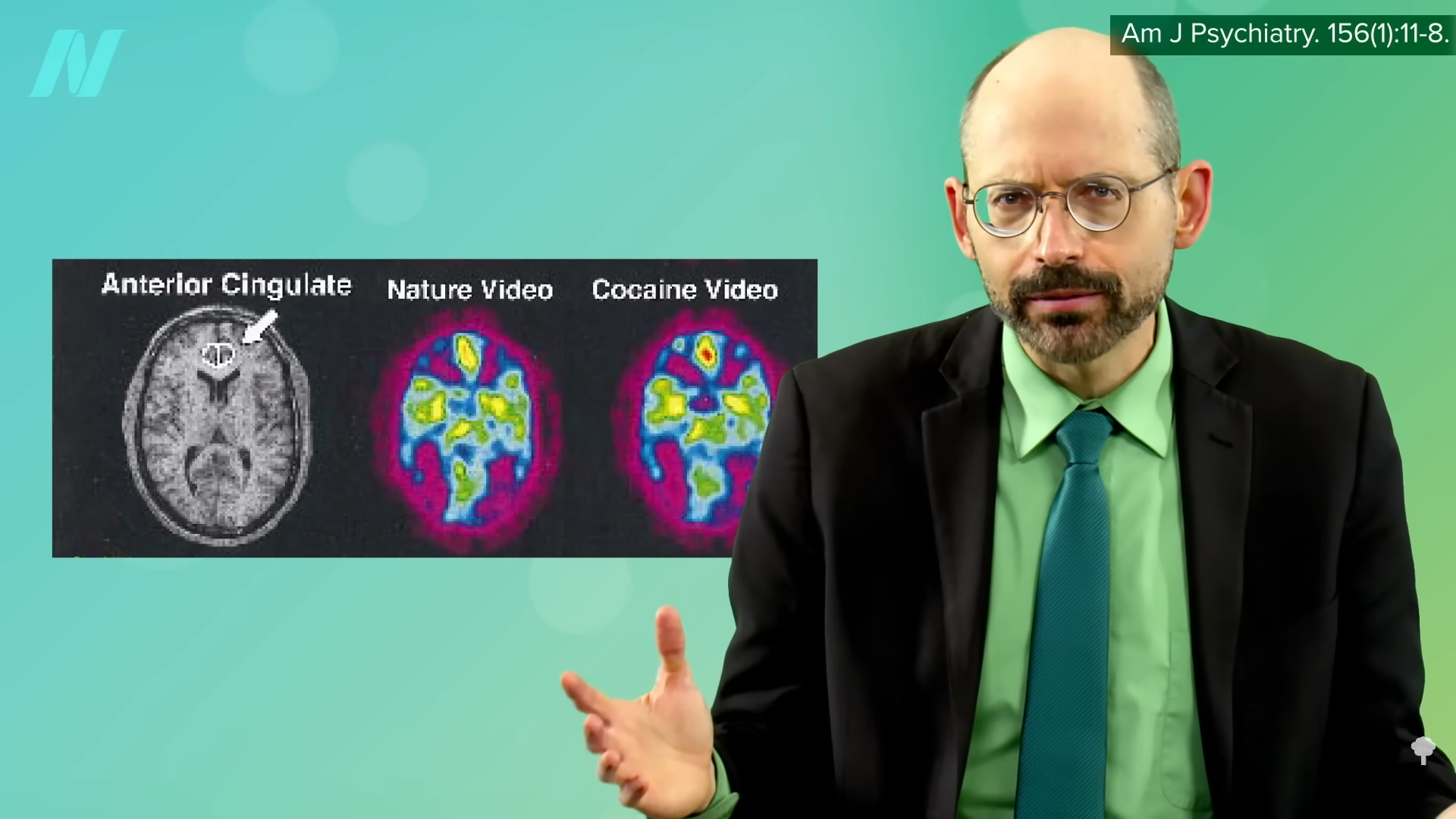

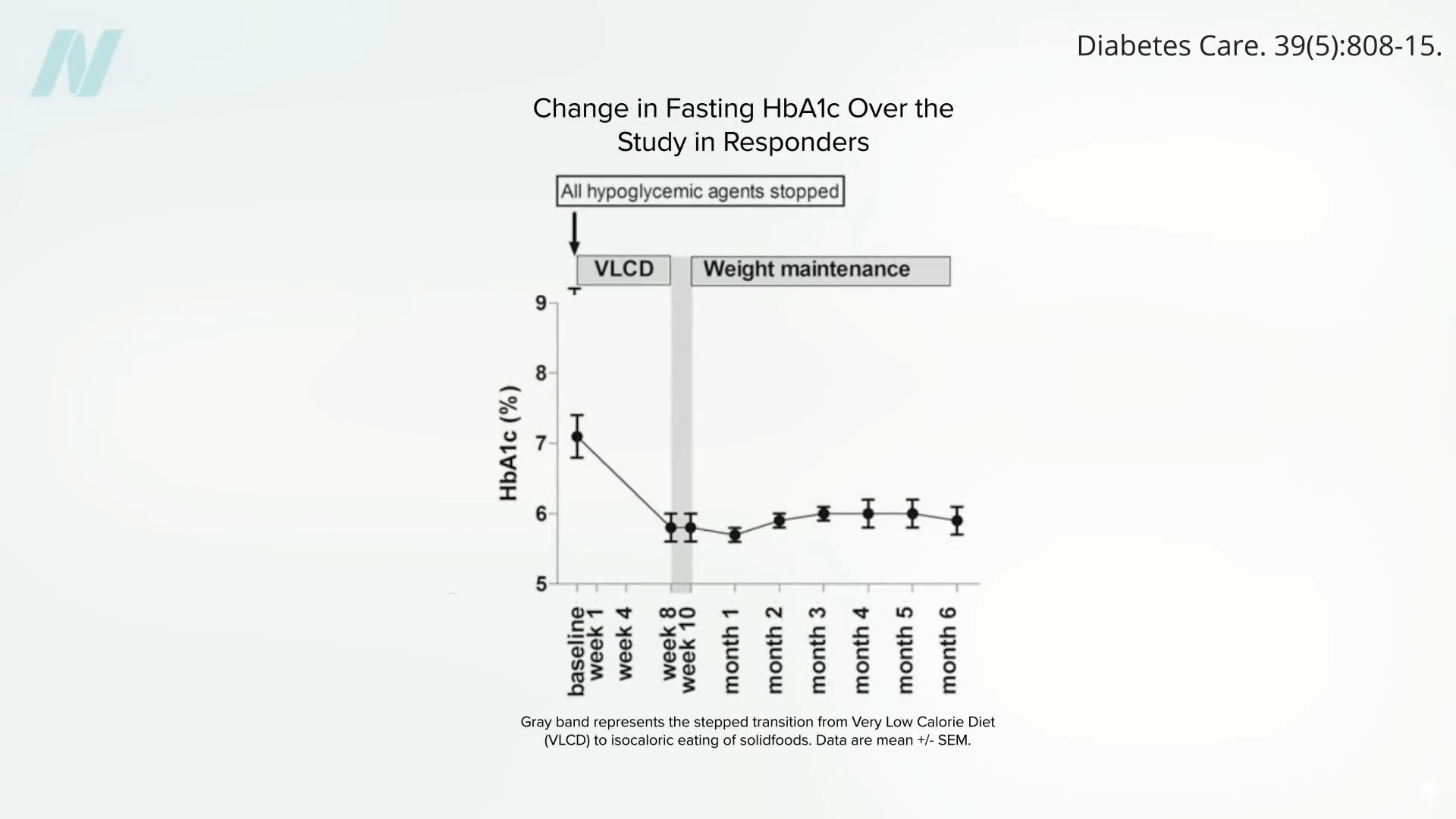

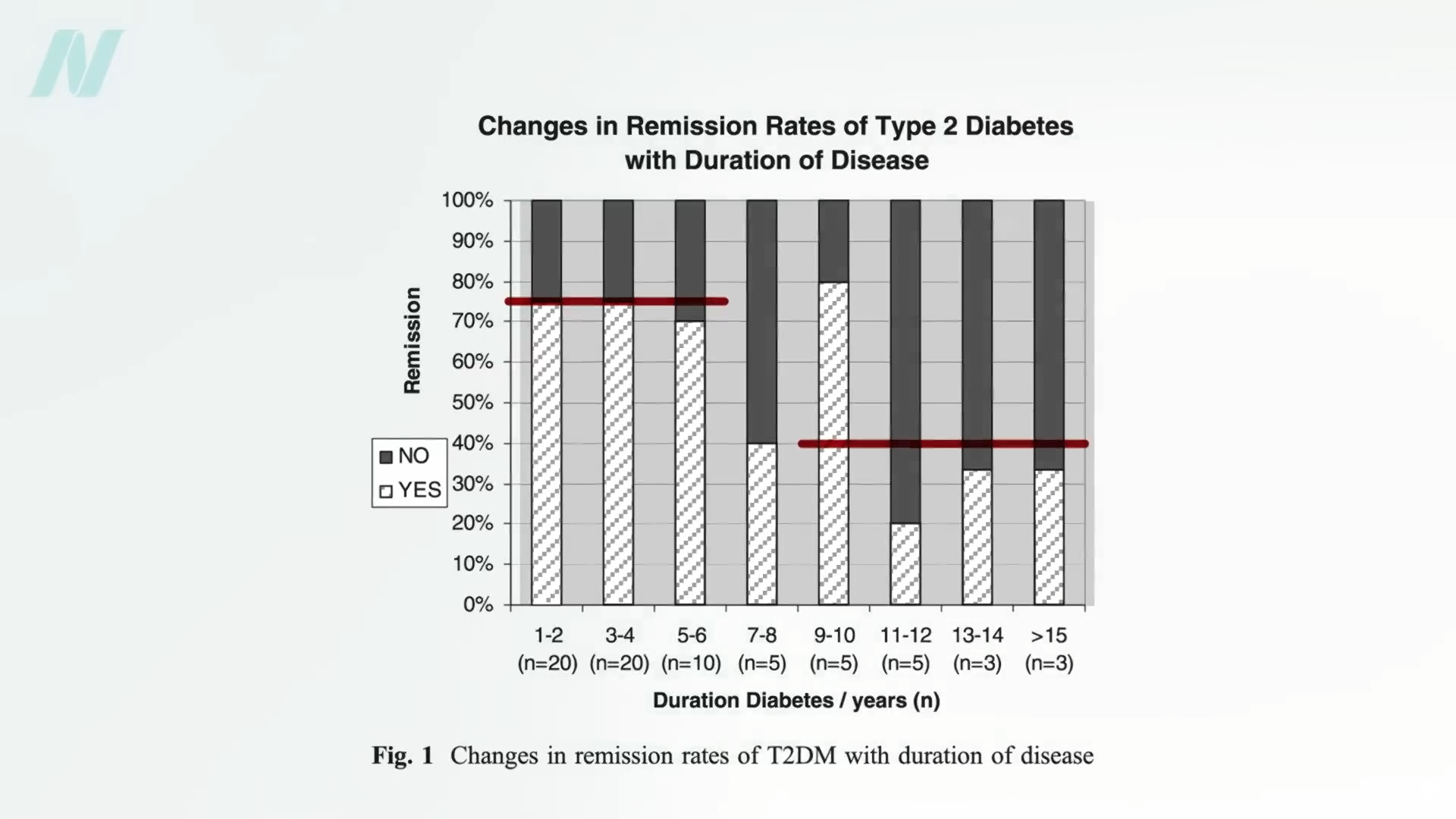

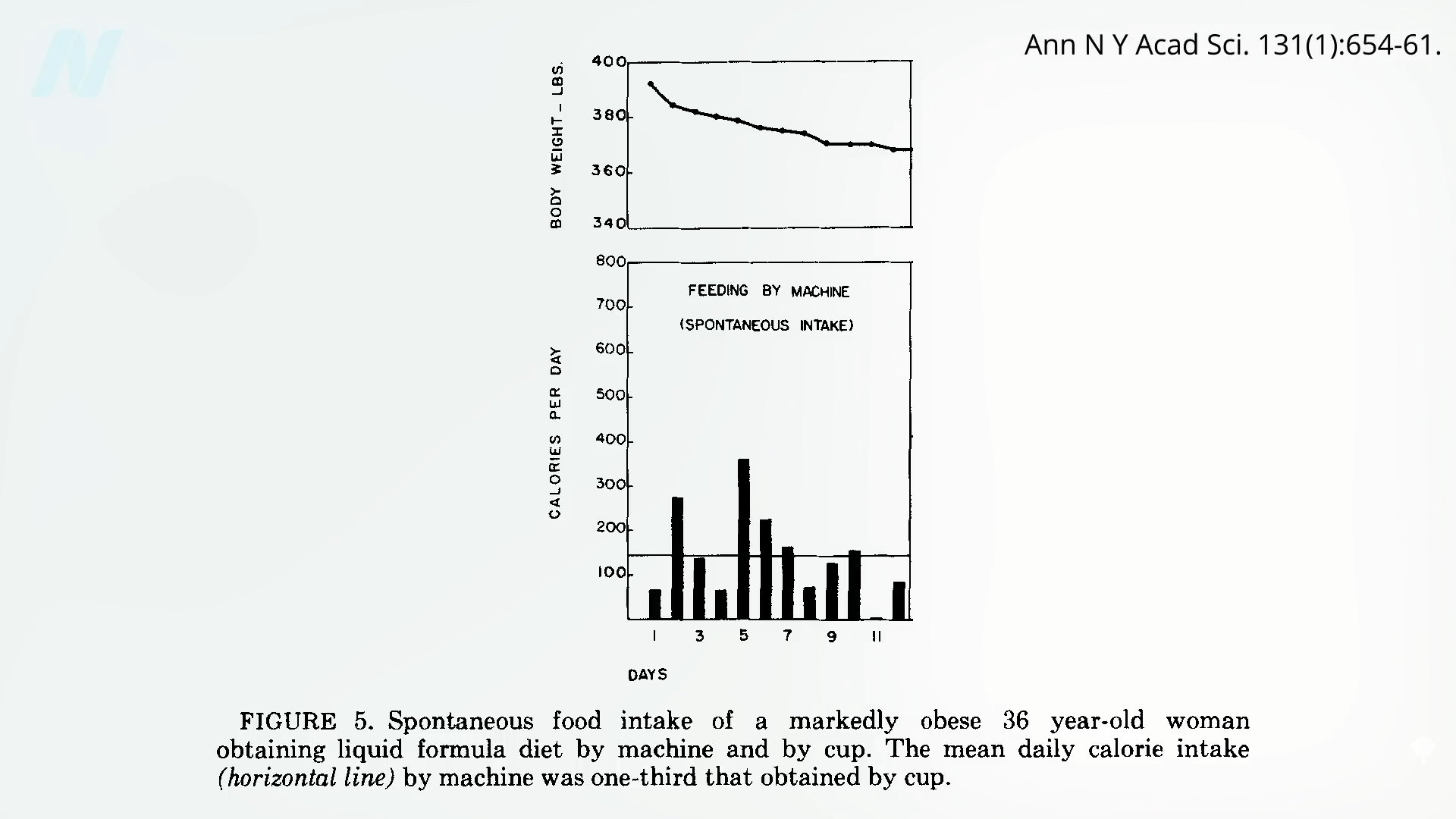

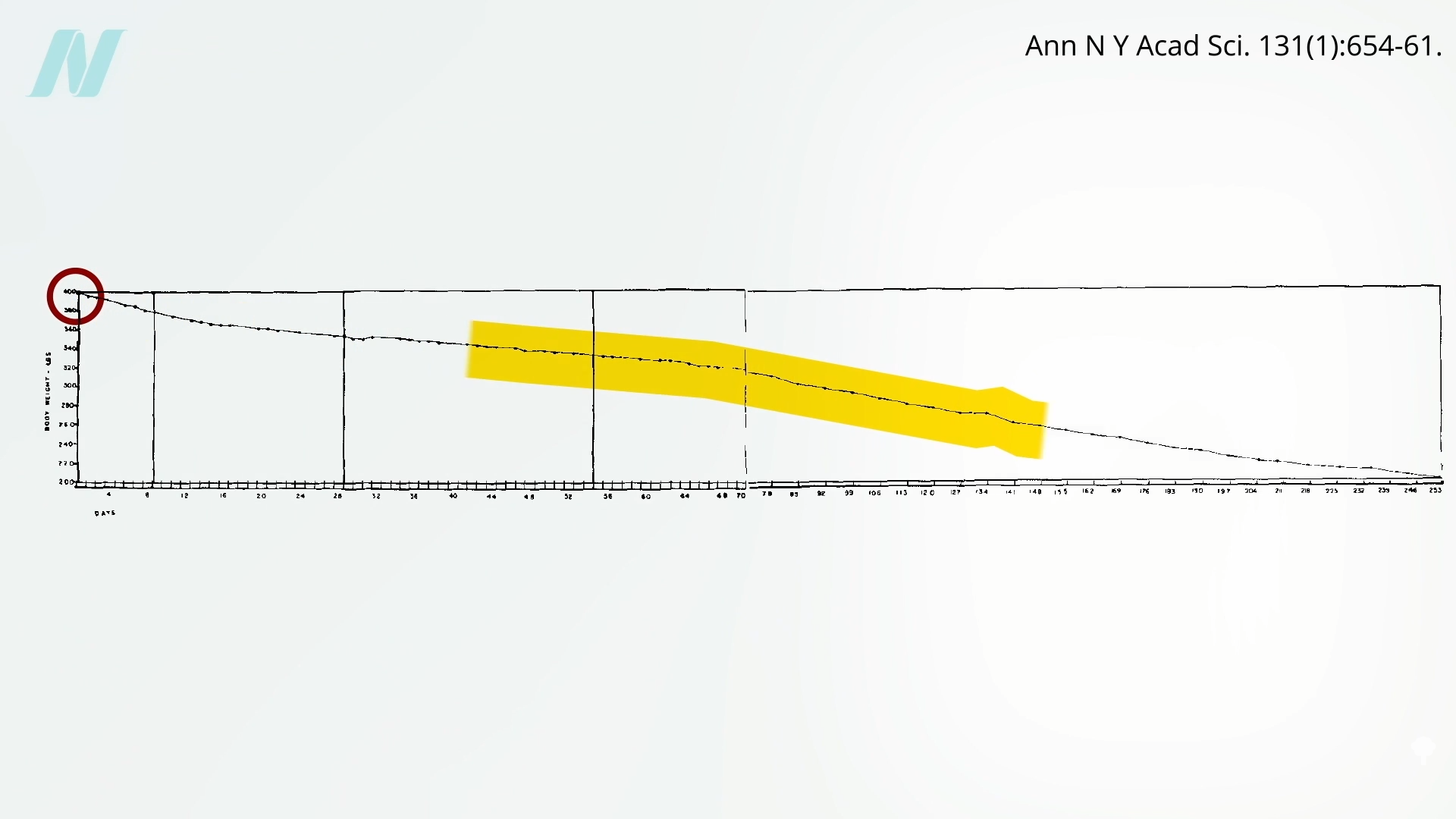

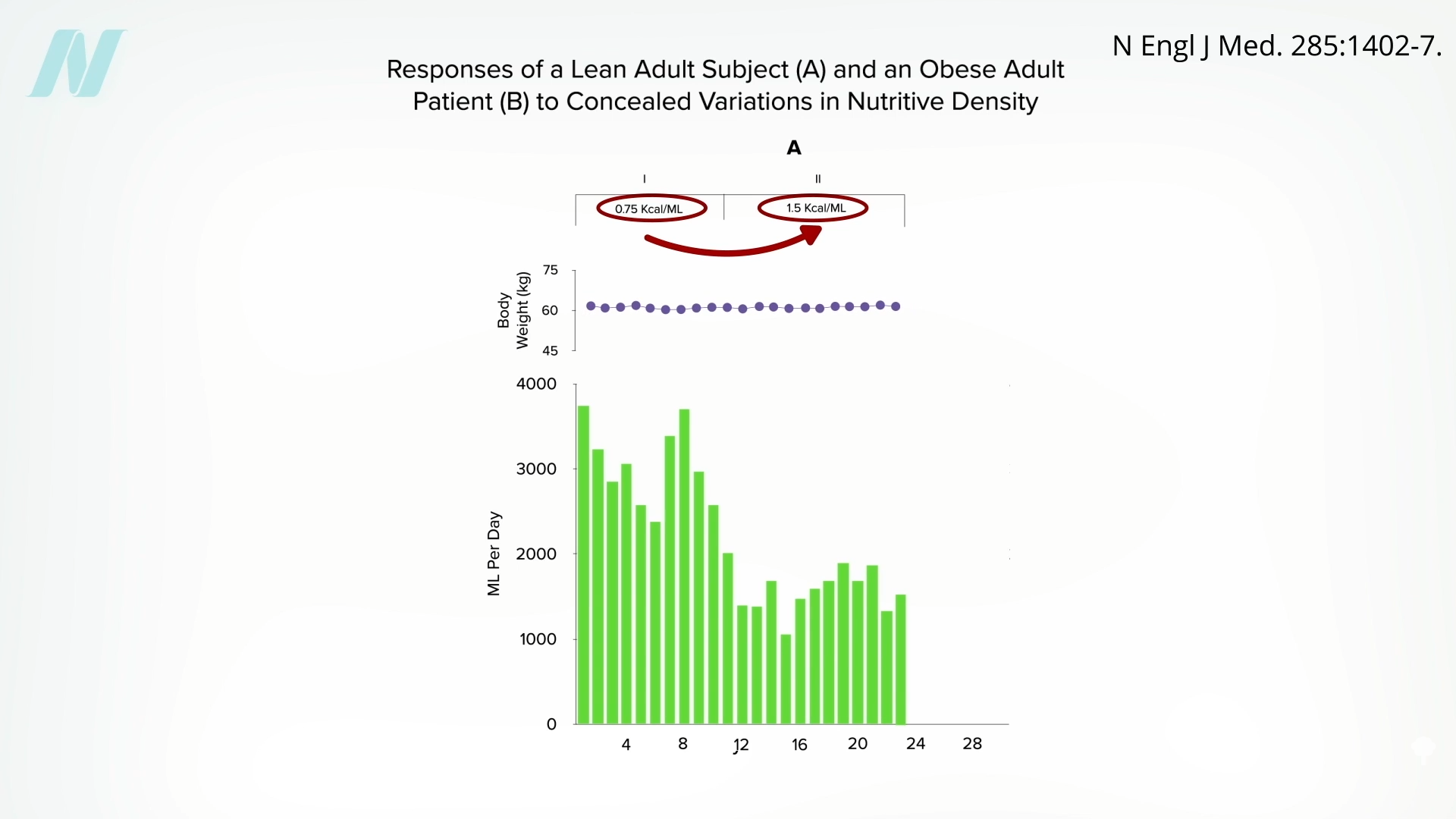

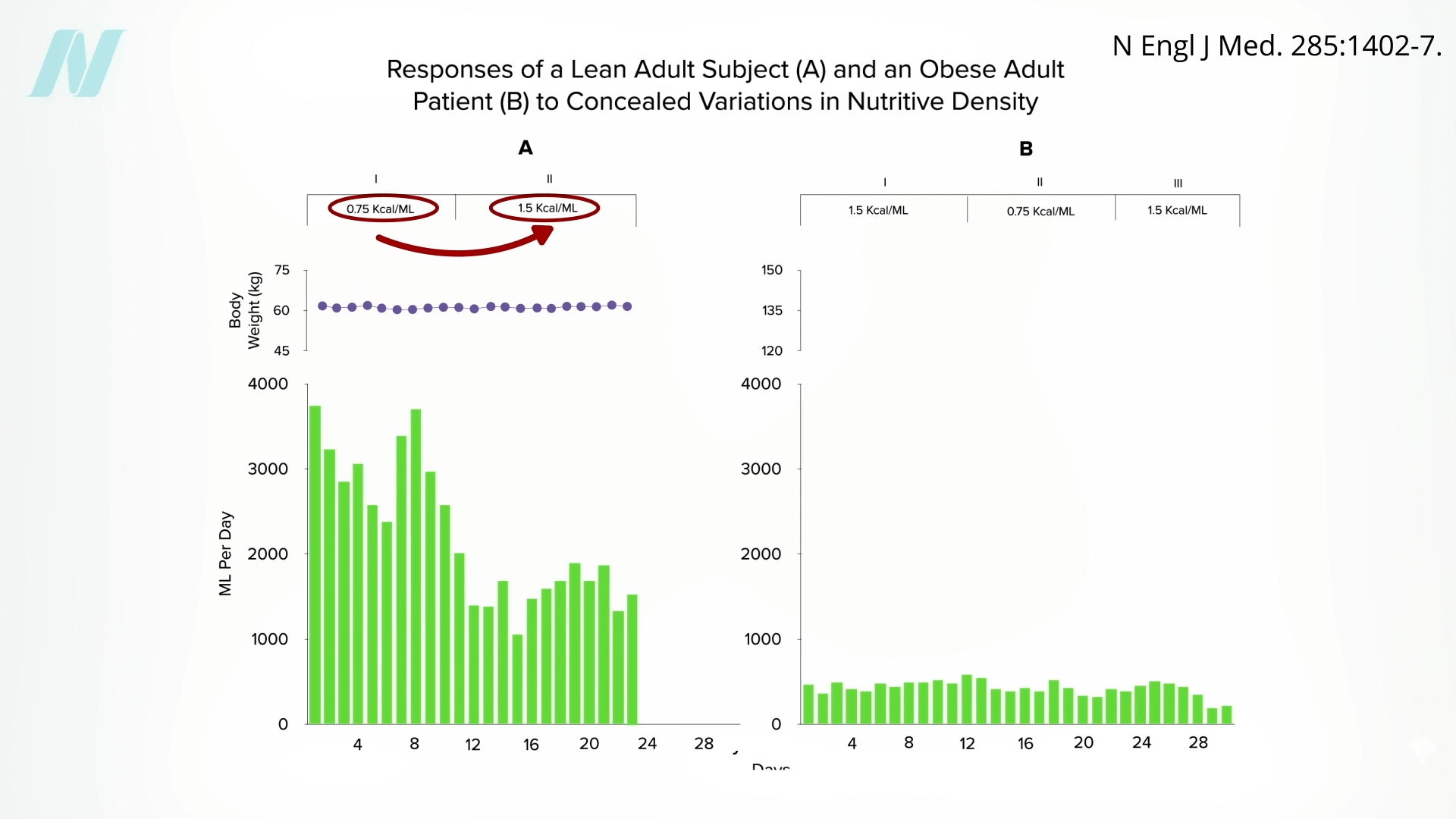

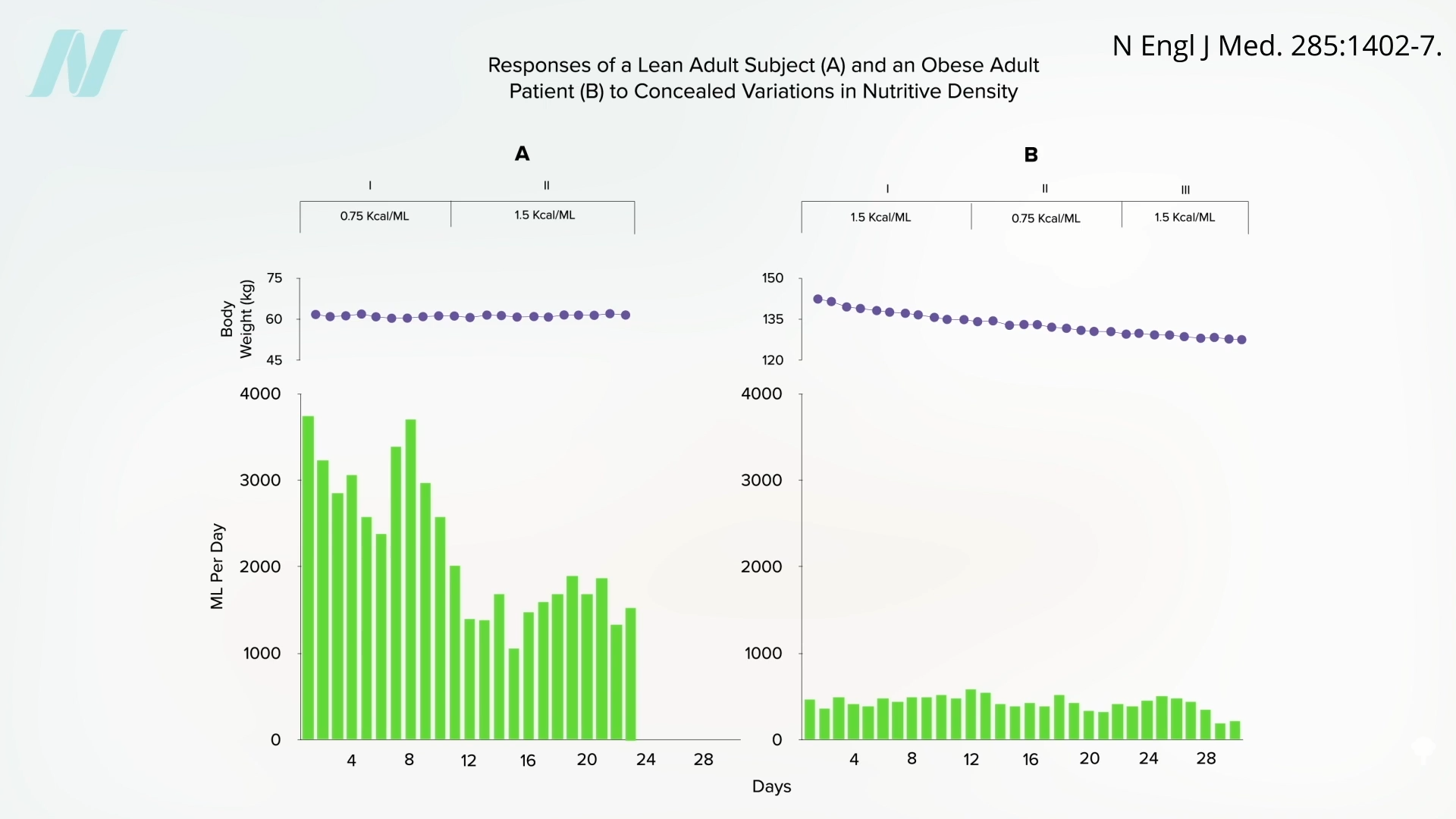

Might the brains of persons with obesity somehow

Might the brains of persons with obesity somehow  It would be interesting to see if they regained the ability to respond to changing calorie intake once they reached their ideal weight. Regardless, what can we apply from these remarkable studies to facilitate weight loss out in the real world? We’ll explore just that question next.

It would be interesting to see if they regained the ability to respond to changing calorie intake once they reached their ideal weight. Regardless, what can we apply from these remarkable studies to facilitate weight loss out in the real world? We’ll explore just that question next.