Alexis Misko’s health has improved enough that, once a month, she can leave her house for a few hours. First, she needs to build up her energy by lying in a dark room for the better part of two days, doing little more than listening to audiobooks. Then she needs a driver, a quiet destination where she can lie down, and days of rest to recover afterward. The brief outdoor joy “never quite feels like enough,” she told me, but it’s so much more than what she managed in her first year of long COVID, when she couldn’t sit upright for more than an hour or stand for more than 10 minutes. Now, at least, she can watch TV on the same day she takes a shower.

In her previous life, she pulled all-nighters in graduate school and rough shifts at her hospital as an occupational therapist; she went for long runs and sagged after long flights. None of that compares with what she has endured since getting COVID-19 almost three years ago. The fatigue she now feels is “like a complete depletion of the essence of who you are, of your life force,” she told me in an email.

Fatigue is among the most common and most disabling of long COVID’s symptoms, and a signature of similar chronic illnesses such as myalgic encephalomyelitis (also known as chronic fatigue syndrome or ME/CFS). But in these diseases, fatigue is so distinct from everyday weariness that most of the people I have talked with were unprepared for how severe, multifaceted, and persistent it can be.

For a start, this fatigue isn’t really a single symptom; it has many faces. It can weigh the body down: Lisa Geiszler likens it to “wearing a lead exoskeleton on a planet with extremely high gravity, while being riddled with severe arthritis.” It can rev the body up: Many fatigued people feel “wired and tired,” paradoxically in fight-or-flight mode despite being utterly depleted. It can be cognitive: Thoughts become sluggish, incoherent, and sometimes painful—like “there’s steel wool stuck in my frontal lobe,” Gwynn Dujardin, a literary historian with ME, told me.

Fatigue turns the most mundane of tasks into an “agonizing cost-benefit analysis,” Misko said. If you do laundry, how long will you need to rest to later make a meal? If you drink water, will you be able to reach the toilet? Only a quarter of long-haulers have symptoms that severely limit their daily activities, but even those with “moderate” cases are profoundly limited. Julia Moore Vogel, a program director at Scripps Research, still works, but washing her hair, she told me, leaves her as exhausted as the long-distance runs she used to do.

And though normal fatigue is temporary and amenable to agency—even after a marathon, you can will yourself into a shower, and you’ll feel better after sleeping—rest often fails to cure the fatigue of long COVID or ME/CFS. “I wake up fatigued,” Letícia Soares, who has long COVID, told me.

Between long COVID, ME/CFS, and other energy-limiting chronic illnesses, millions of people in the U.S. alone experience debilitating fatigue. But American society tends to equate inactivity with immorality, and productivity with worth. Faced with a condition that simply doesn’t allow people to move—even one whose deficits can be measured and explained—many doctors and loved ones default to disbelief. When Soares tells others about her illness, they usually say, “Oh yeah, I’m tired too.” When she was bedbound for days, people told her, “I need a weekend like that.” Soares’s problems are very real, and although researchers have started to figure out why so many people like her are suffering, they don’t yet know how to stop it.

Fatigue creates a background hum of disability, but it can be punctuated by worse percussive episodes that strip long-haulers of even the small amounts of energy they normally have.

Daria Oller is a physiotherapist and athletic trainer, so when she got COVID in March 2020, she naturally tried exercising her way to better health. And she couldn’t understand why, after just short runs, her fatigue, brain fog, chest pain, and other symptoms would flare up dramatically—to the point where she could barely move or speak. These crashes contradicted everything she had learned during her training. Only after talking with physiotherapists with ME/CFS did she realize that this phenomenon has a name: post-exertional malaise.

Post-exertional malaise, or PEM, is the defining trait of ME/CFS and a common feature of long COVID. It is often portrayed as an extreme form of fatigue, but it is more correctly understood as a physiological state in which all existing symptoms burn more fiercely and new ones ignite. Beyond fatigue, people who get PEM might also feel intense radiant pain, an inflammatory burning feeling, or gastrointestinal and cognitive problems: “You feel poisoned, flu-ish, concussed,” Misko said. And where fatigue usually sets in right after exertion, PEM might strike hours or days later, and with disproportionate ferocity. Even gentle physical or mental effort might lay people out for days, weeks, months. Visiting a doctor can precipitate a crash, and so can filling out applications for disability benefits—or sensing bright lights and loud sounds, regulating body temperature on hot days, or coping with stress. And if in fatigue your batteries feel drained, in PEM they’re missing entirely. It’s the annihilation of possibility: Most people experience the desperation of being unable to move only in nightmares, Dujardin told me. “PEM is like that, but much more painful.”

Medical professionals generally don’t learn about PEM during their training. Many people doubt its existence because it is so unlike anything that healthy people endure. Mary Dimmock told me that she understood what it meant only when she saw her son, Matthew, who has ME/CFS, crash in front of her eyes. “He just melted,” Dimmock said. But most people never see such damage because PEM hides those in the midst of it from public view. And because it usually occurs after a delay, people who experience PEM might appear well to friends and colleagues who then don’t witness the exorbitant price they later pay.

That price is both real and measurable. In cardiopulmonary exercise tests, or CPETs, patients use treadmills or exercise bikes while doctors record their oxygen consumption, blood pressure, and heart rate. Betsy Keller, an exercise physiologist at Ithaca College, told me that most people can repeat their performance if retested one day later, even if they have heart disease or are deconditioned by inactivity. People who get PEM cannot. Their results are so different the second time around that when Keller first tested someone with ME/CFS in 2003, “I told my colleagues that our equipment was out of calibration,” she said. But she and others have seen the same pattern in hundreds of ME/CFS and long-COVID patients—“objective findings that can’t be explained by anything psychological,” David Systrom, a pulmonologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, told me. “Many patients are told it’s all in their head, but this belies that in spades.” Still, many insurers refuse to pay for a second test, and many patients cannot do two CPETs (or even one) without seriously risking their health. And “20 years later, I still have physicians who refute and ignore the objective data,” Keller said. (Some long-COVID studies have ignored PEM entirely, or bundled it together with fatigue.)

Oller thinks this dismissal arises because PEM inverts the dogma that exercise is good for you—an adage that, for most other illnesses, is correct. “It’s not easy to change what you’ve been doing your whole career, even when I tell someone that they might be harming their patients,” she said. Indeed, many long-haulers get worse because they don’t get enough rest in their first weeks of illness, or try to exercise through their symptoms on doctors’ orders.

People with PEM are also frequently misdiagnosed. They’re told that they’re deconditioned from being too sedentary, when their inactivity is the result of frequent crashes, not the cause. They’re told that they’re depressed and unmotivated, when they are usually desperate to move and either physically incapable of doing so or using restraint to avoid crashing. Oller is part of a support group of 1,500 endurance athletes with long COVID who are well used to running, swimming, and biking through pain and tiredness. “Why would we all just stop?” she asked.

Some patients with energy-limiting illnesses argue that the names of their diseases and symptoms make them easier to discredit. Fatigue invites people to minimize severe depletion as everyday tiredness. Chronic fatigue syndrome collapses a wide-ranging disabling condition into a single symptom that is easy to trivialize. These complaints are valid, but the problem runs deeper than any name.

Dujardin, the English professor who is (very slowly) writing a cultural history of fatigue, thinks that our concept of it has been impoverished by centuries of reductionism. As the study of medicine slowly fractured into anatomical specialties, it lost an overarching sense of the systems that contribute to human energy, or its absence. The concept of energy was (and still is) central to animistic philosophies, and though once core to the Western world, too, it is now culturally associated with quackery and pseudoscience. “There are vials of ‘energy boosters’ by every cash register in the U.S.,” Dujardin said, but when the NIH convened a conference on the biology of fatigue in 2021, “specialists kept observing that no standard definition exists for fatigue, and everyone was working from different ideas of human energy.” These terms have become so unhelpfully unspecific that our concept of “fatigue” can encompass a wide array of states including PEM and idleness, and can be heavily influenced by social forces—in particular the desire to exploit the energy of others.

As the historian Emily K. Abel notes in Sick and Tired: An Intimate History of Fatigue, many studies of everyday fatigue at the turn of the 20th century focused on the weariness of manual laborers, and were done to find ways to make those workers more productive. During this period, fatigue was recast from a physiological limit that employers must work around into a psychological failure that individuals must work against. “Present-day society stigmatizes those who don’t Push through; keep at it; show grit,” Dujardin said, and for the sin of subverting those norms, long-haulers “are not just disbelieved but treated openly with contempt.” Fatigue is “profoundly anti-capitalistic,” Jaime Seltzer, the director of scientific and medical outreach at the advocacy group MEAction, told me.

Energy-limiting illnesses also disproportionately affect women, who have long been portrayed as prone to idleness. Dujardin notes that in Western epics, women such as Circe and Dido were perceived harshly for averting questing heroes such as Odysseus and Aeneas with the temptation of rest. Later, the onset of industrialization turned women instead into emblems of homebound idleness while men labored in public. As shirking work became a moral failure, it also remained a feminine one.

These attitudes were evident in the ways two successive U.S. presidents dealt with COVID. Donald Trump, who always evinced a caricature of masculine strength and chastised rivals for being “low energy,” framed his recovery from the coronavirus as an act of domination. Joe Biden was less bombastic, but he still conspicuously assured the public that he was working through his COVID infection while his administration prioritized policies that got people back to work. Neither man spoke of the possibility of disabling fatigue or the need for rest.

Medicine, too, absorbs society’s stigmas around fatigue, even in selecting those who get to join its ranks. Its famously grueling training programs exclude (among others) most people with energy-limiting illnesses, while valorizing the ability to function when severely depleted. This, together with the tendency to psychologize women’s pain, helps to explain why so many long-haulers—even those with medical qualifications, like Misko and Oller—are treated so badly by the professionals they see for care. When Dujardin first sought medical help for her ME/CFS symptoms, the same doctor who had treated her well for a decade suddenly became stiff and suspicious, she told me, reduced all of her detailed descriptions to “tiredness,” and left the room without offering diagnosis or treatment. There is so much cultural pressure to never stop that many people can’t accept that their patients or peers might be biologically forced to do so.

No grand unified theory explains everything about long COVID and ME/CFS, but neither are these diseases total mysteries. In fact, plenty of evidence exists for at least two pathways that explain why people with these conditions could be so limited in energy.

First, most people with energy-limiting chronic illnesses have problems with their autonomic nervous system, which governs heartbeat, breathing, sleep, hormone release, and other bodily functions that we don’t consciously control. When this system is disrupted—a condition called “dysautonomia”—hormones such as adrenaline might be released at inappropriate moments, leading to the wired-but-tired feeling. People might suddenly feel sleepy, as if they’re shutting down. Blood vessels might not expand in moments of need, depriving active muscles and organs of oxygen and fuel; those organs might include the brain, leading to cognitive dysfunction such as brain fog.

Second, many people with long COVID and ME/CFS have problems with generating energy. When viruses invade the body, the immune system counterattacks, triggering a state of inflammation. Both infection and inflammation can damage the mitochondria—the bean-shaped batteries that power our cells. Malfunctioning mitochondria produce violent chemicals called “reactive oxygen species” (ROS) that inflict even more cellular damage. Inflammation also triggers a metabolic switch toward fast but inefficient ways of making energy, depleting cells of fuel and riddling them with lactic acid. These changes collectively explain the pervasive, dead-battery flavor of fatigue, as “the body struggles to generate energy,” Bindu Paul, a pharmacologist and neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins, told me. They might also explain the burning, poisoned feelings that patients experience, as their cells fill with lactic acid and ROS.

These two pathways—autonomic and metabolic—might also account for PEM. Normally, the autonomic nervous system smoothly dials up to an intense fight-and-flight mode and down to a calmer rest-and-digest one. But “in dysautonomia, the dial becomes a switch,” David Putrino, a neuroscientist and rehabilitation specialist at Mount Sinai, told me. “You go from sitting to standing and your body thinks: Oh, are we going hunting? You stop, and your body shuts down.” The exhaustion of these dramatic, unstable flip-flops is made worse by the ongoing metabolic maelstrom. Damaged mitochondria, destructive ROS, inefficient metabolism, and chronic inflammation all compound one another in a vicious cycle that, if it becomes sufficiently intense, could manifest as a PEM crash. “No one is absolutely certain about what causes PEM,” Seltzer told me, but it makes sense that “you have this big metabolic shift and your nervous system can’t get back on an even keel.” And if people push through, deepening the metabolic demands on a body that already can’t meet them, the cycle can spin even faster, “leading to progressive disability,” Putrino said.

Other factors might also be at play. Compared with healthy people, those with long COVID and ME/CFS have differences in the size, structure, or function of brain regions including the thalamus, which relays motor signals and regulates consciousness, and the basal ganglia, which controls movement and has been implicated in fatigue. Long-haulers also have problems with blood vessels, red blood cells, and clotting, all of which might further staunch their flows of blood, oxygen, and nutrients. “I’ve tested so many of these people over the years, and we see over and over again that when the systems start to fail, they all fail in the same way,” Keller said. Together, these woes explain why long COVID and ME/CFS have such bewilderingly varied symptoms. That diversity fuels disbelief—how could one disease cause all of this?—but it’s exactly what you’d expect if things as fundamental as metabolism go awry.

Long-haulers might not know the biochemical specifics of their symptoms, but they are uncannily good at capturing those underpinnings through metaphor. People experiencing autonomic blood-flow problems might complain about feeling “drained,” and that’s literally happening: In POTS, a form of dysautonomia, blood pools in the lower body when people stand. People experiencing metabolic problems often use dead-battery analogies, and indeed their cellular batteries—the mitochondria—are being damaged: “It really feels like something is going wrong at the cellular level,” Oller told me. Attentive doctors can find important clues about the basis of their patients’ illness hiding amid descriptions that are often billed as “exaggerated or melodramatic,” Dujardin said.

Some COVID long-haulers do recover. But several studies have found that, so far, most don’t fully return to their previous baseline, and many who become severely ill stay that way. This pool of persistently sick people is now mired in the same neglect that has long plagued those who suffer from illnesses such as ME/CFS. Research into such conditions are grossly underfunded, so no cures exist. Very few doctors in the U.S. know how to treat these conditions, and many are nearing retirement, so patients struggle to find care. Long-COVID clinics exist but vary in quality: Some know nothing about other energy-limiting illnesses, and still prescribe potentially harmful and officially discouraged treatments such as exercise. Clinicians who better understand these illnesses know that caution is crucial. When Putrino works with long-haulers to recondition their autonomic nervous system, he always starts as gently as possible to avoid triggering PEM. Such work “isn’t easy and isn’t fast,” he said, and it usually means stabilizing people instead of curing them.

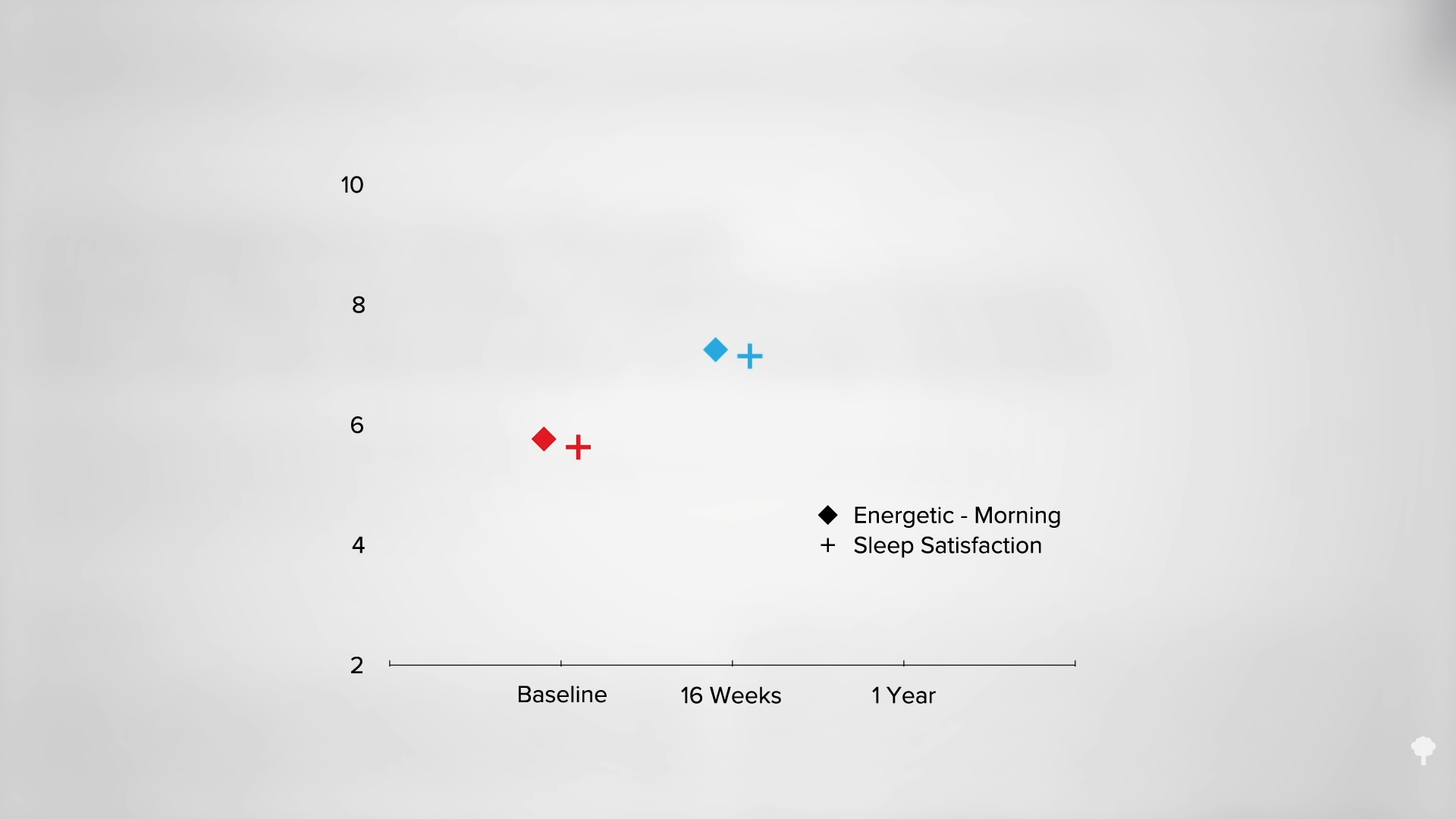

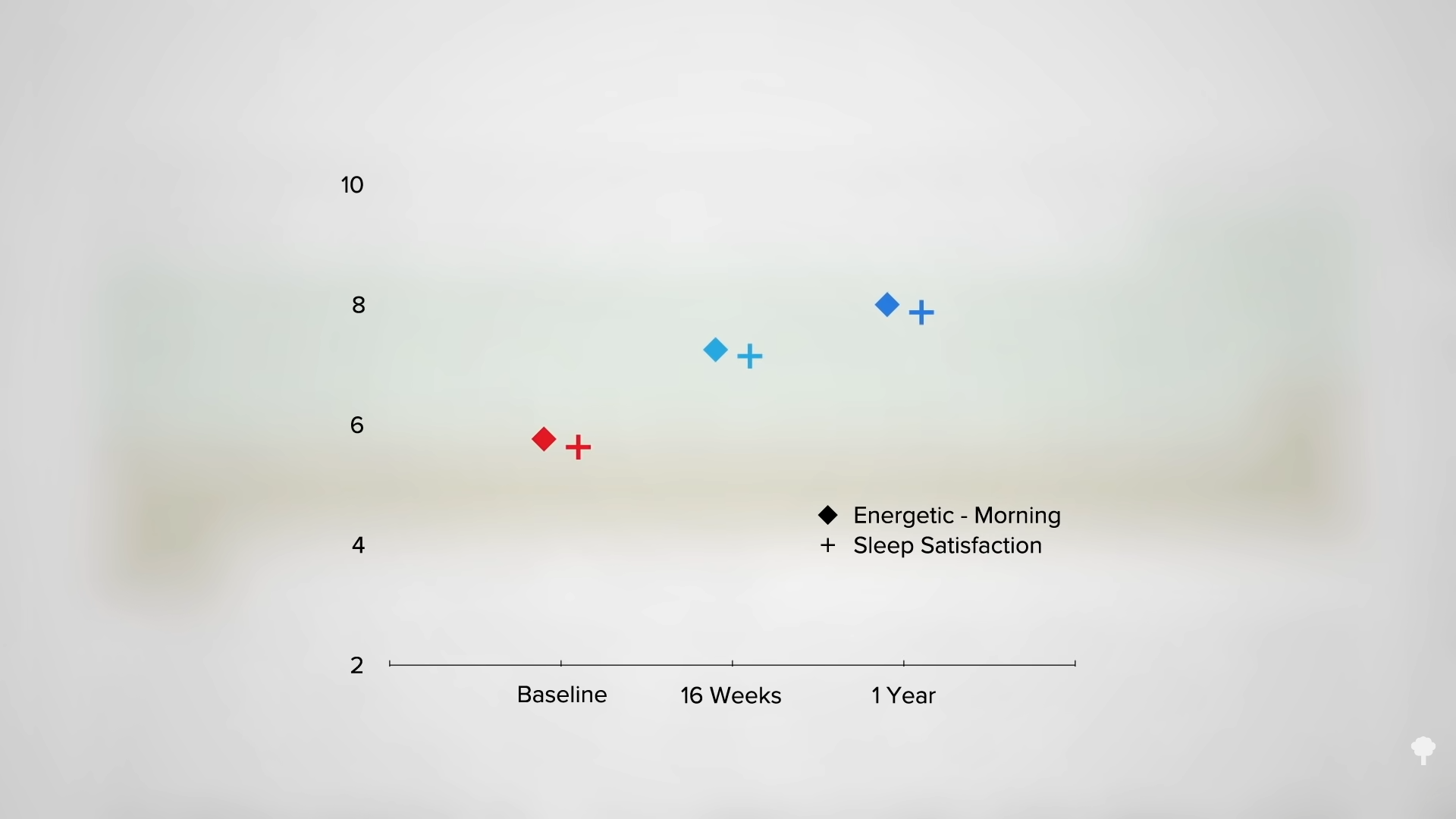

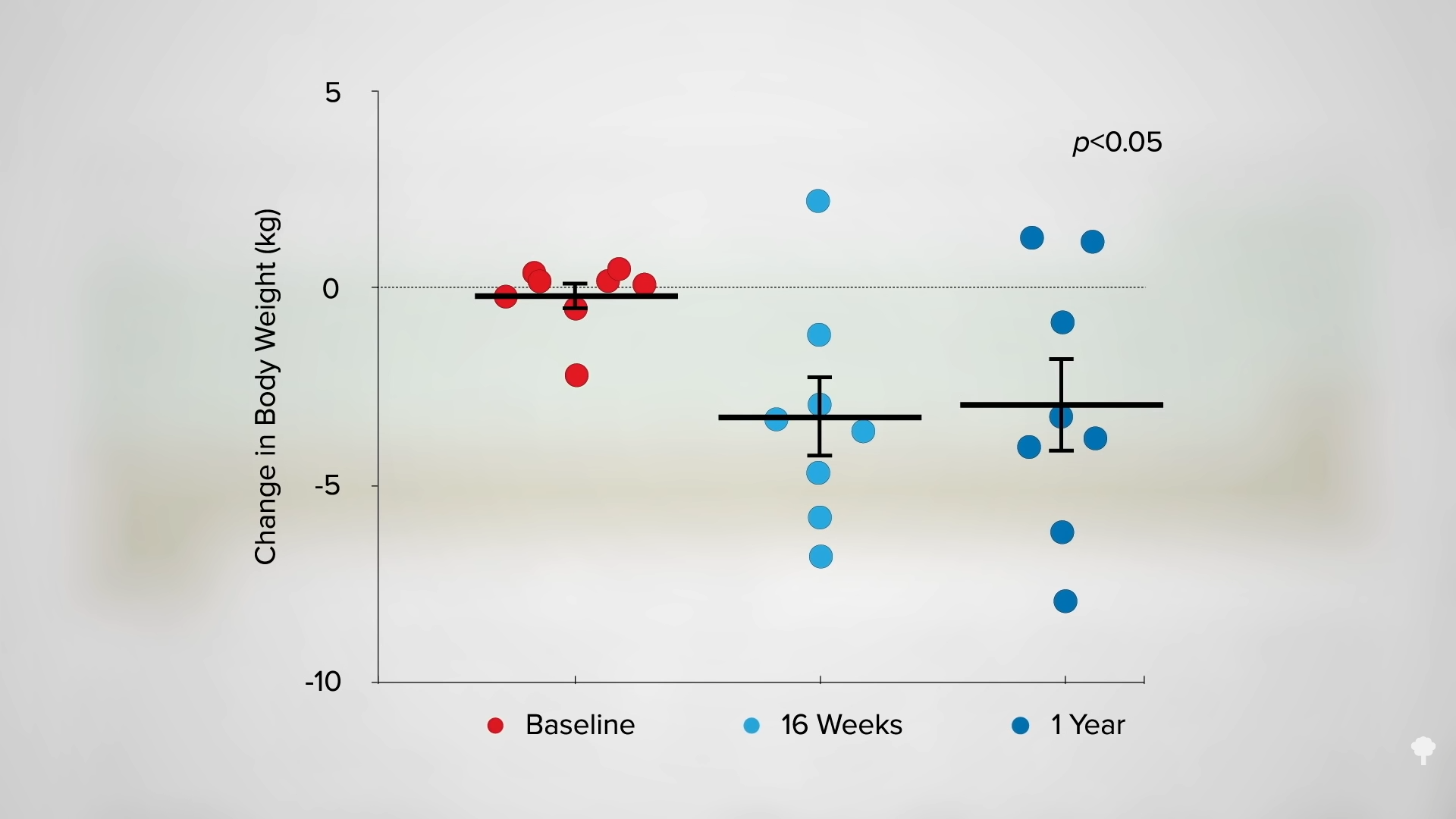

Stability can be life-changing, especially when it involves changes that patients can keep up at home. Over-the-counter supplements such as coenzyme Q10, which is used by mitochondria to generate energy and is depleted in ME/CFS patients, can reduce fatigue. Anti-inflammatory medications such as low-dose naltrexone may have some promise. Sleep hygiene may not cure fatigue, but certainly makes it less debilitating. Dietary changes can help, but the right ones might be counterintuitive: High-fiber foods take more energy to digest, and some long-haulers get PEM episodes after eating meals that seem healthy. And the most important part of this portfolio is “pacing”—a strategy for carefully keeping your activity levels beneath the threshold that causes debilitating crashes.

Pacing is more challenging than it sounds. Practitioners can’t rely on fixed routines; instead, they must learn to gauge their fluctuating energy levels in real time, while becoming acutely aware of their PEM triggers. Some turn to wearable technology such as heart-rate monitors, and more than 30,000 are testing a patient-designed app called Visible to help spot patterns in their illness. Such data are useful, but the difference between rest and PEM might be just 10 or 20 extra heartbeats a minute—a narrow crevice into which long-haulers must squeeze their life. Doing so can be frustrating, because pacing isn’t a recovery tactic; it’s mostly a way of not getting worse, which makes its value harder to appreciate. Its physical benefits come at mental costs: Walks, workouts, socializing, and “all the things I’d do for mental health before were huge energy sinks,” Vogel told me. And without financial stability or social support, many long-haulers must work, parent, and care for themselves even knowing that they’ll suffer later. “It’s impossible not to overdo it, because life is life,” Vogel said.

“Our society is not set up for pacing,” Oller added. Long-haulers must resist the enormous cultural pressure to prove their worth by pushing as hard as they can. They must tolerate being chastised for trying to avert a crash, and being disbelieved if they fail. “One of the most insulting things people can say is ‘Fight your illness,’” Misko said. That would be much easier for her. “It takes so much self-control and strength to do less, to be less, to shrink your life down to one or two small things from which you try to extract joy in order to survive.” For her and many others, rest has become both a medical necessity and a radical act of defiance—one that, in itself, is exhausting.

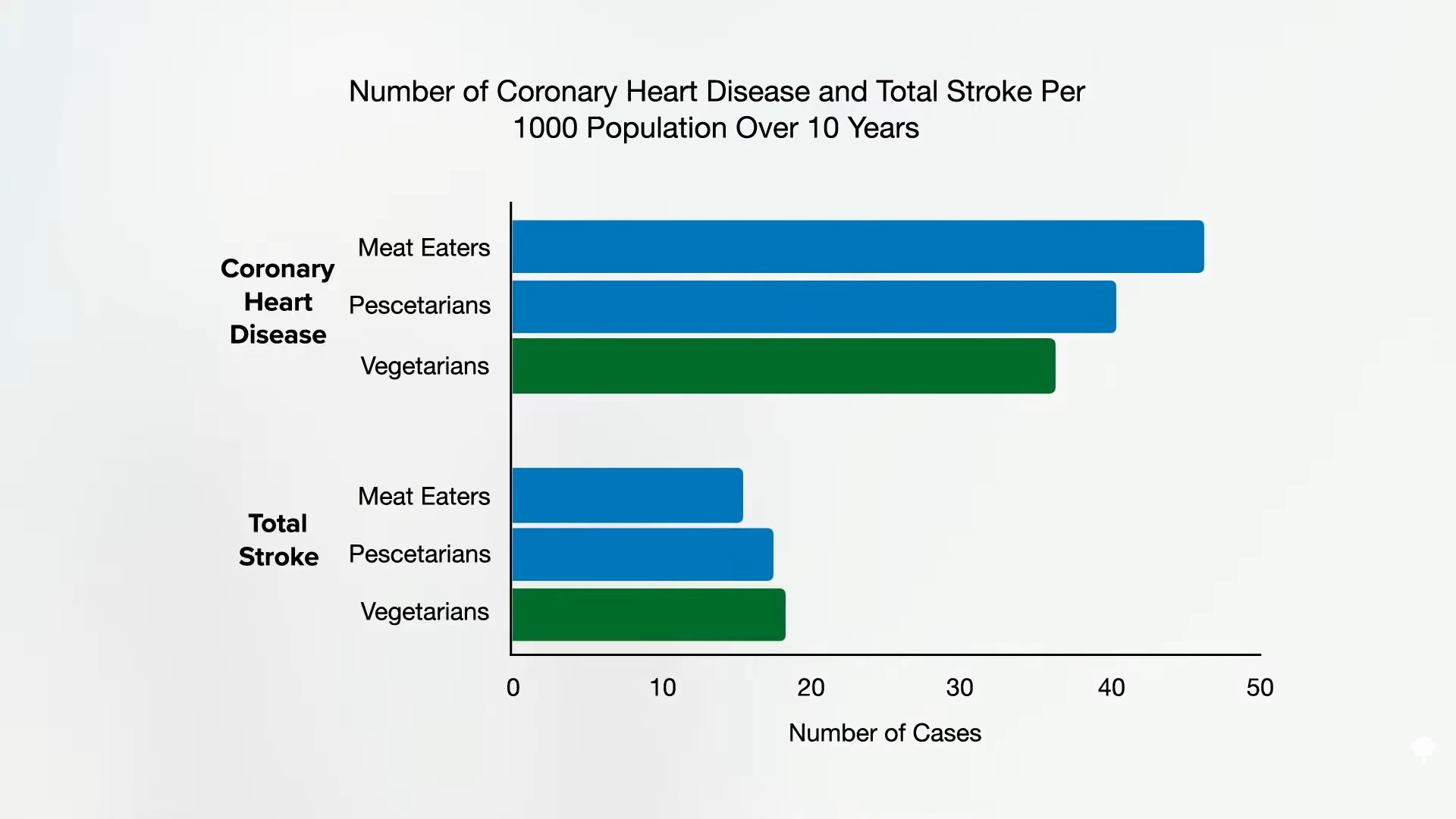

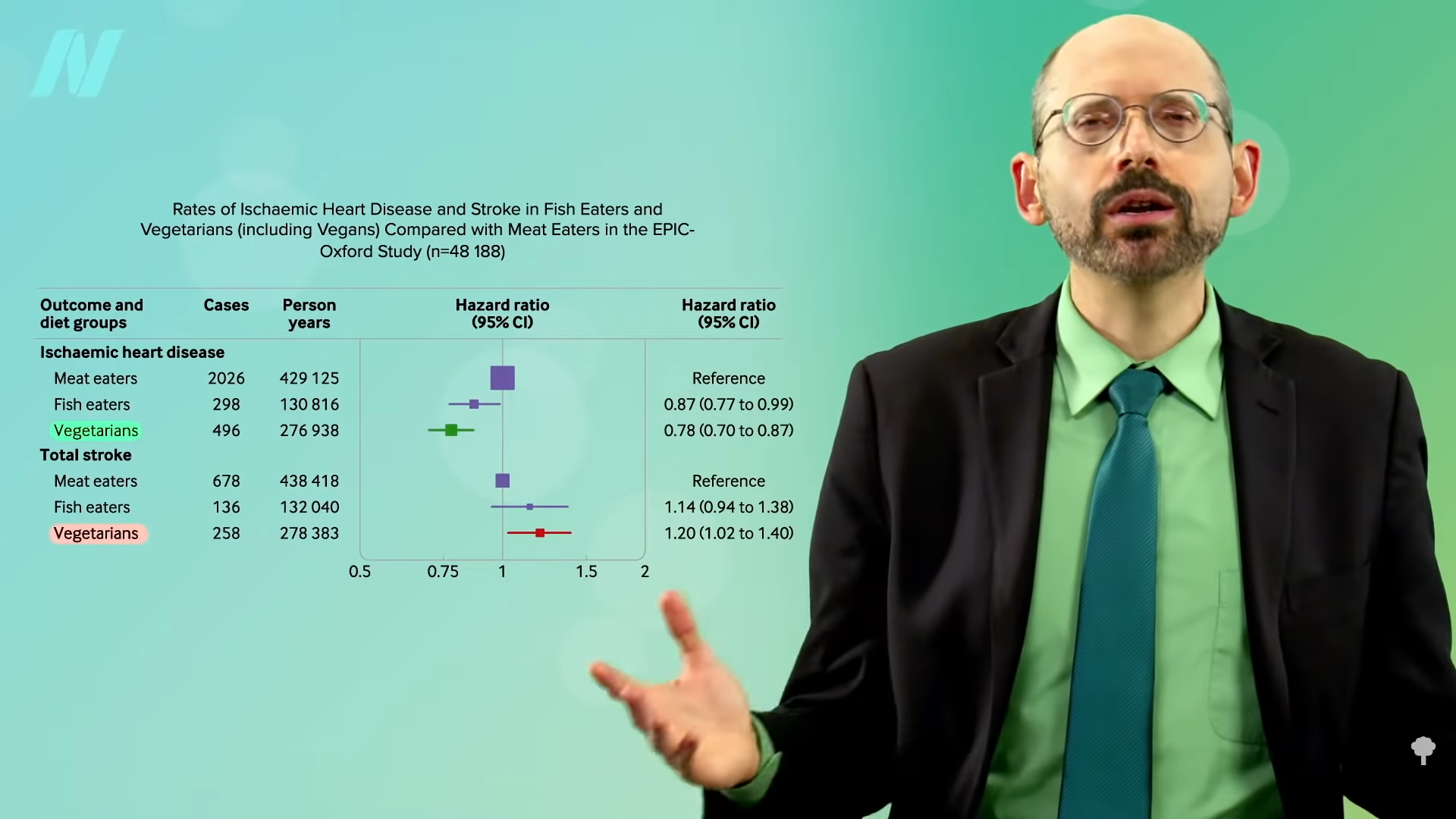

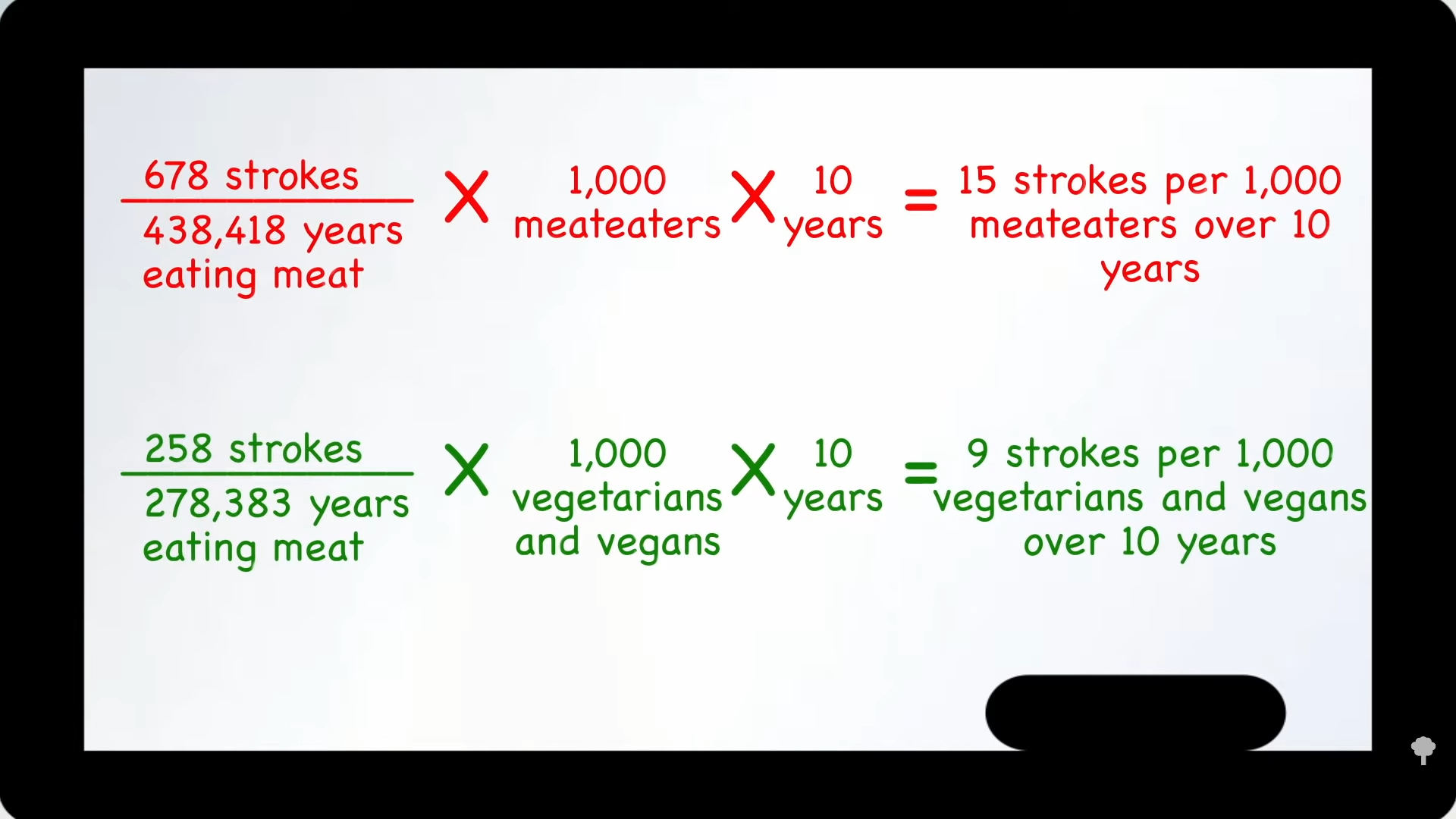

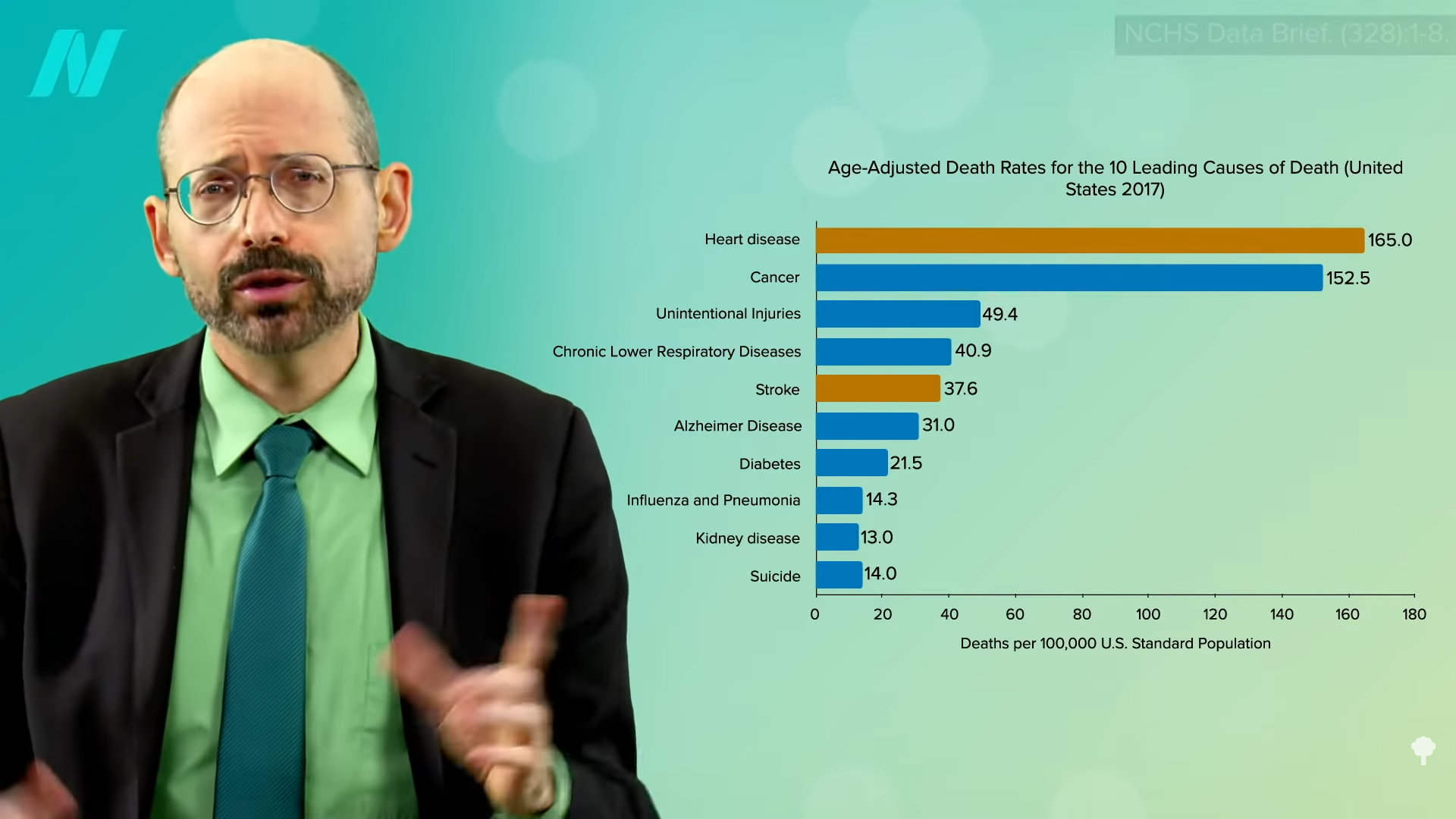

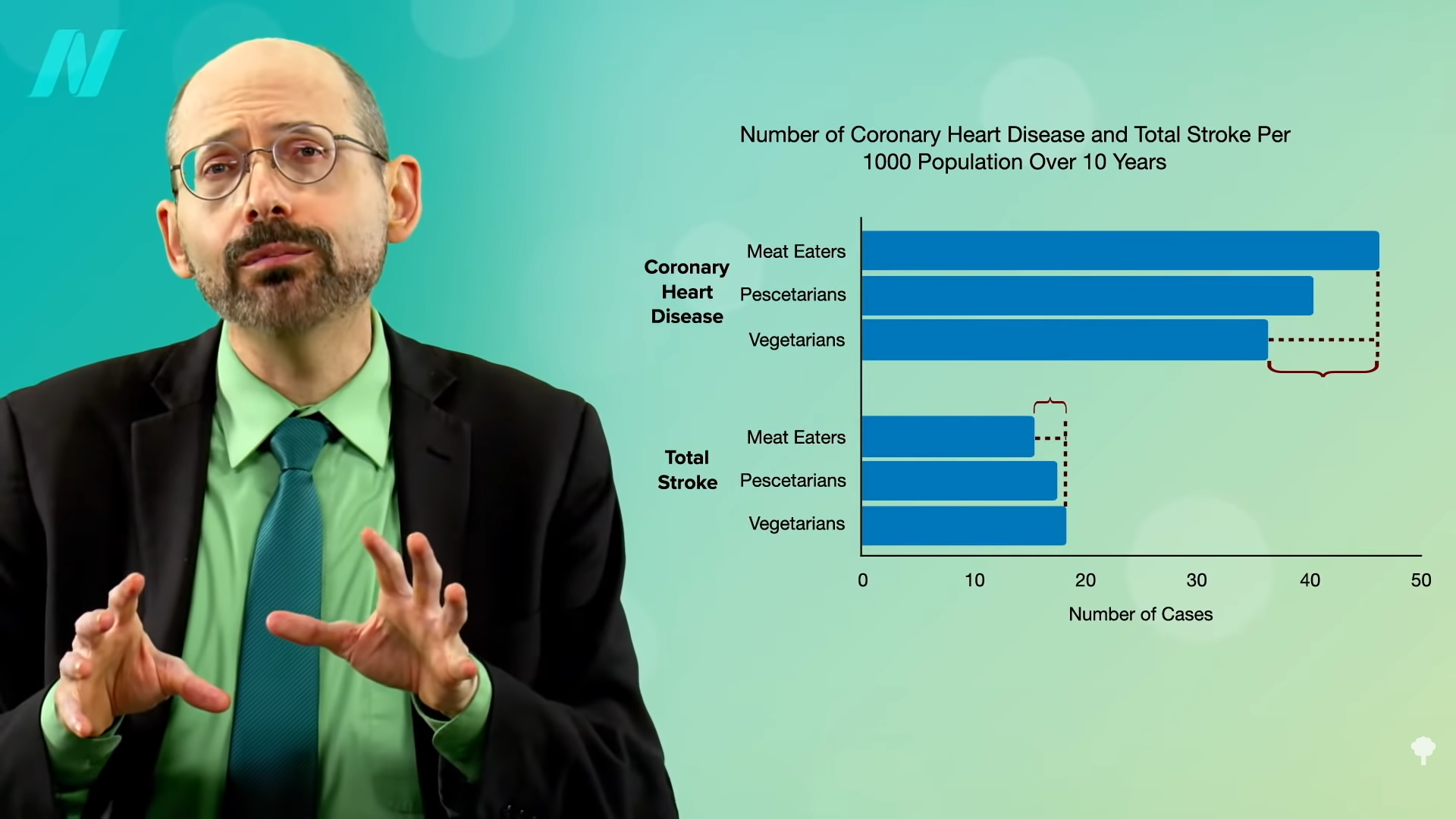

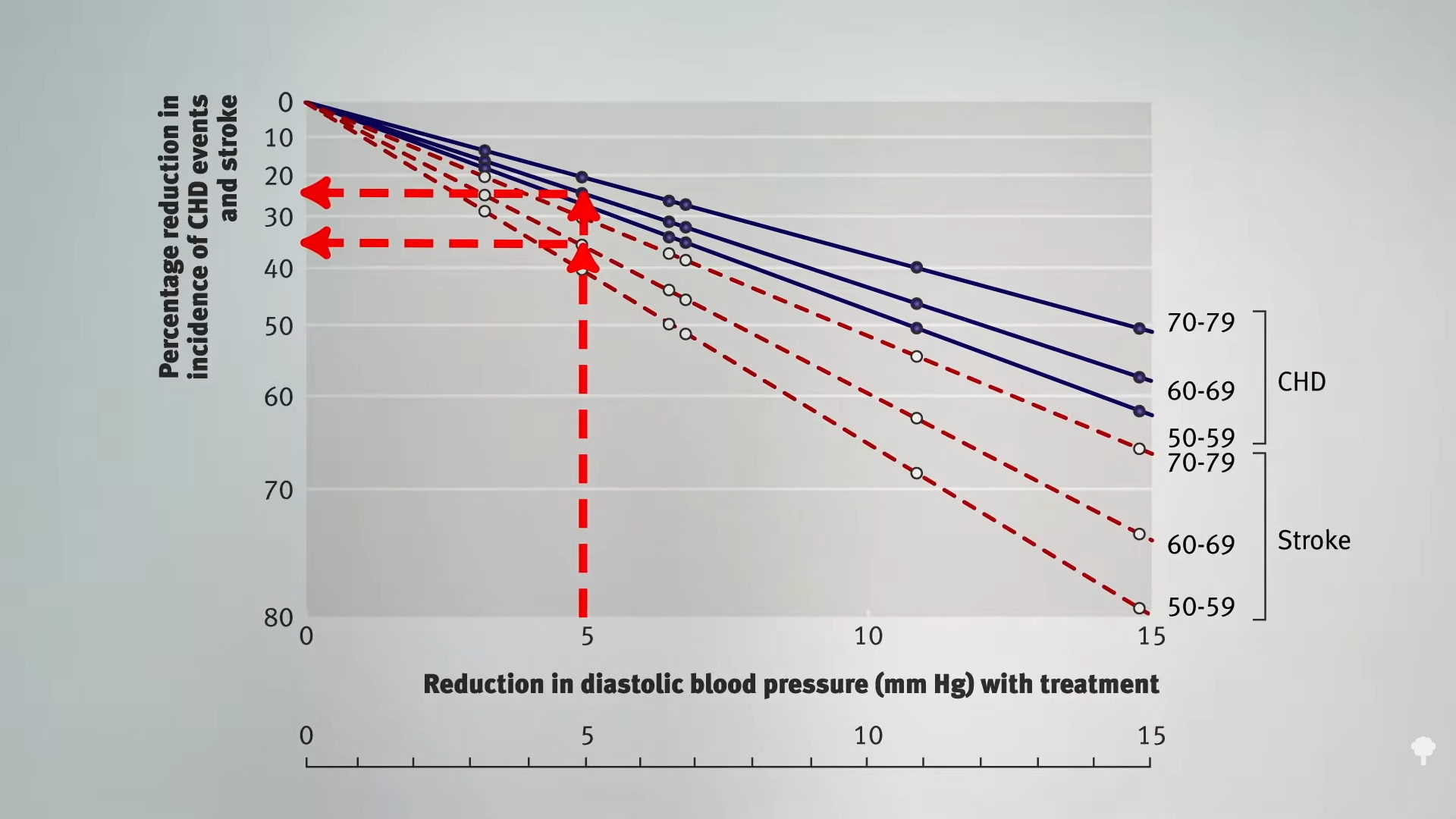

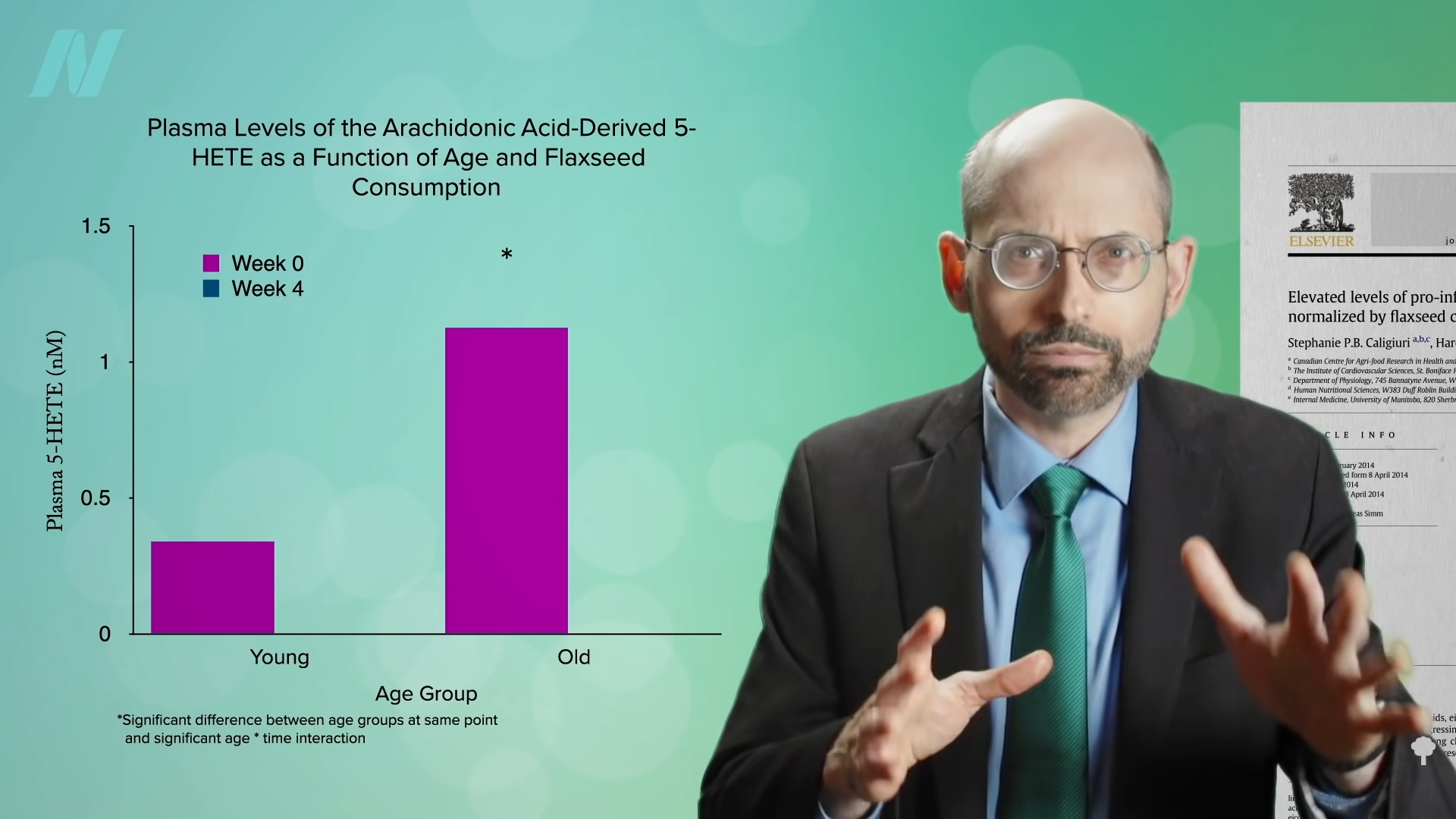

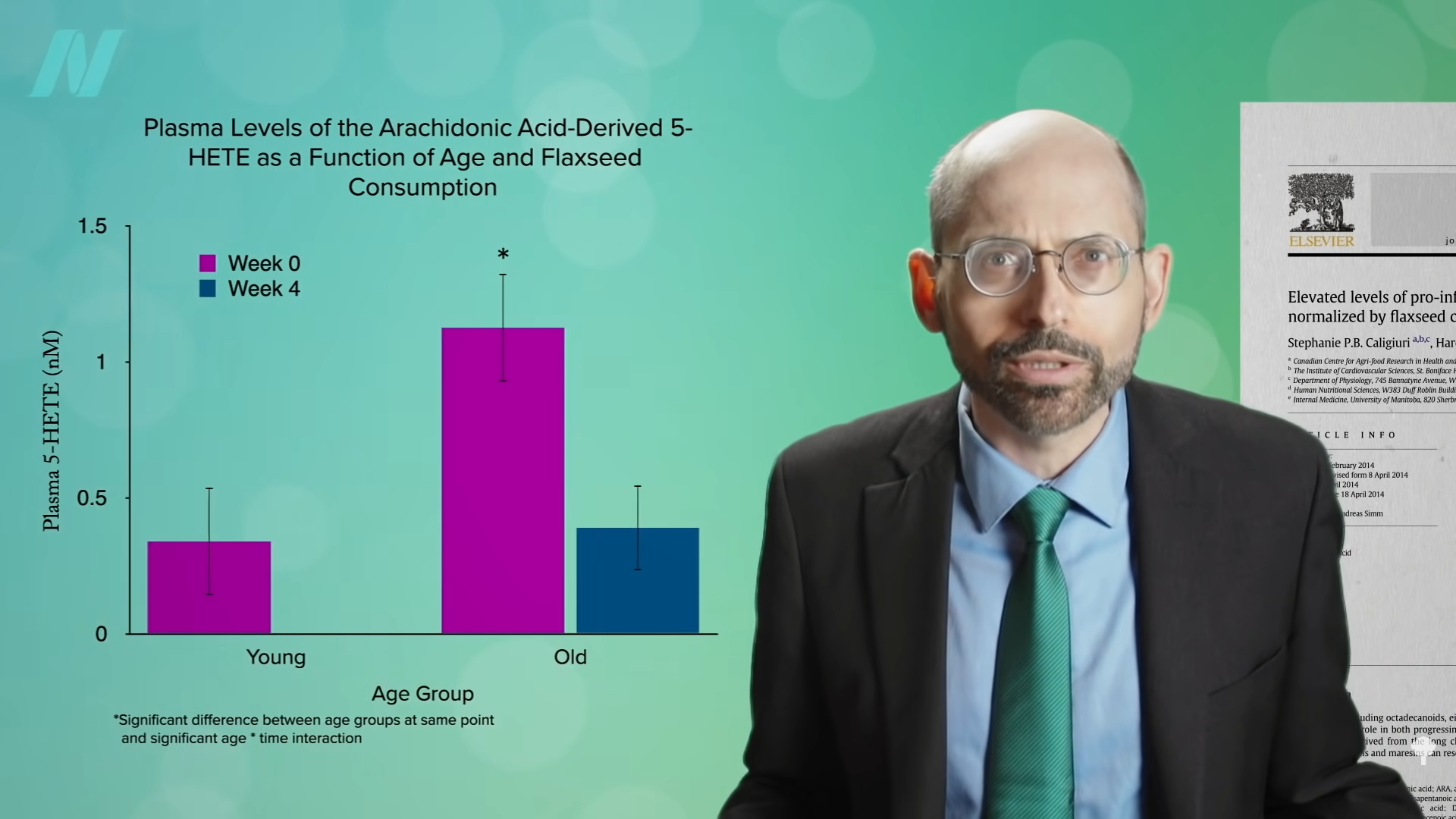

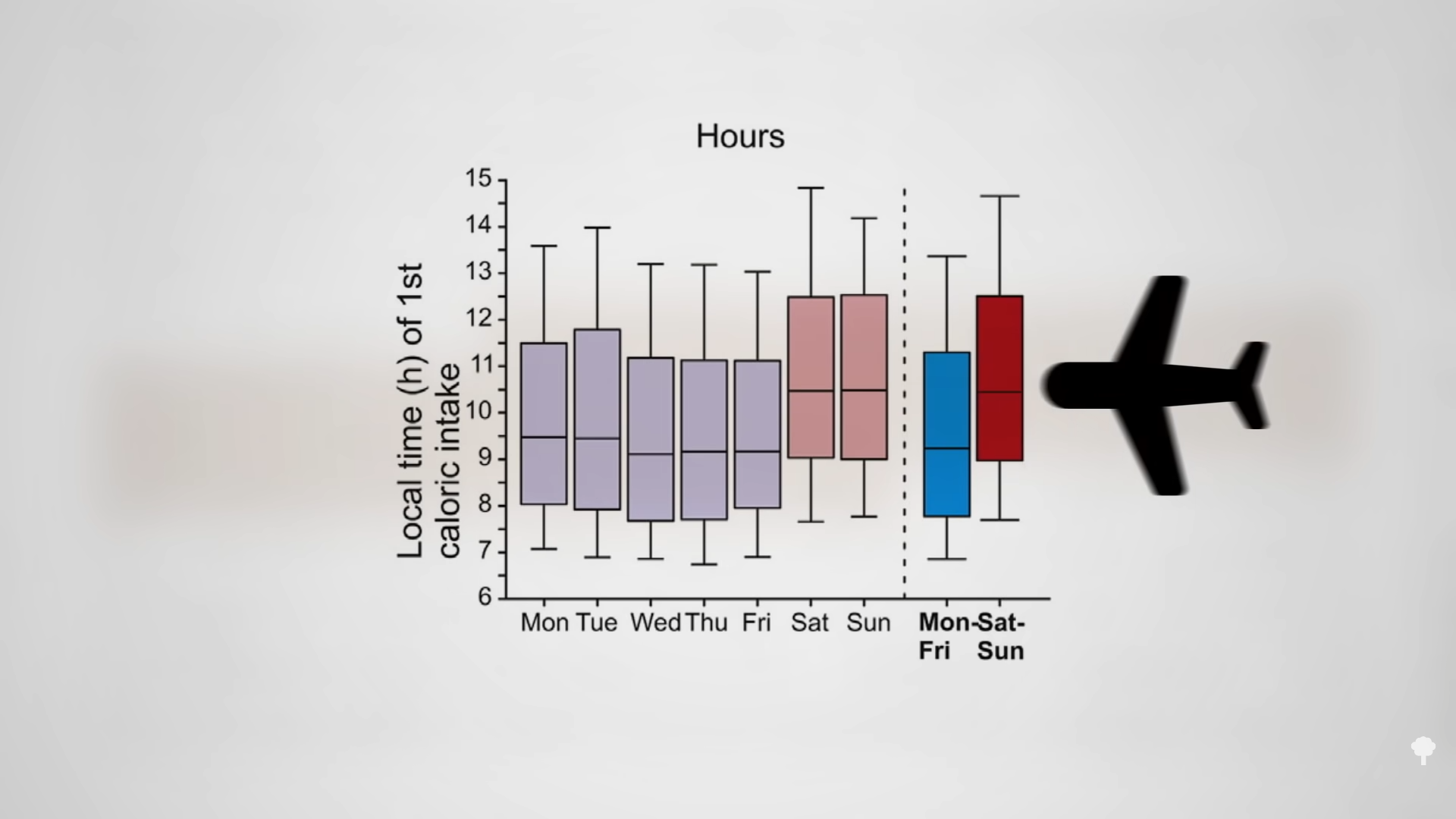

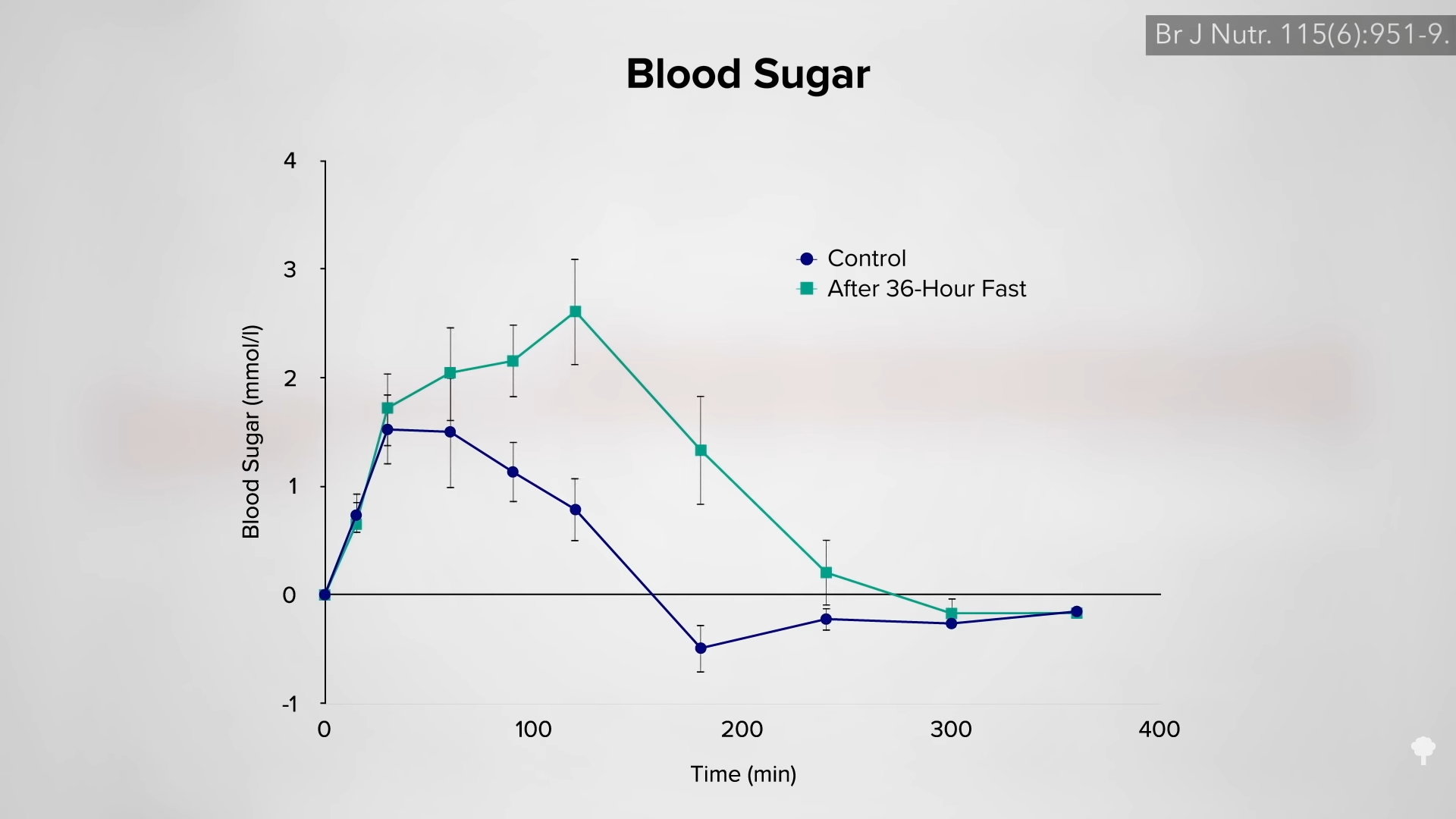

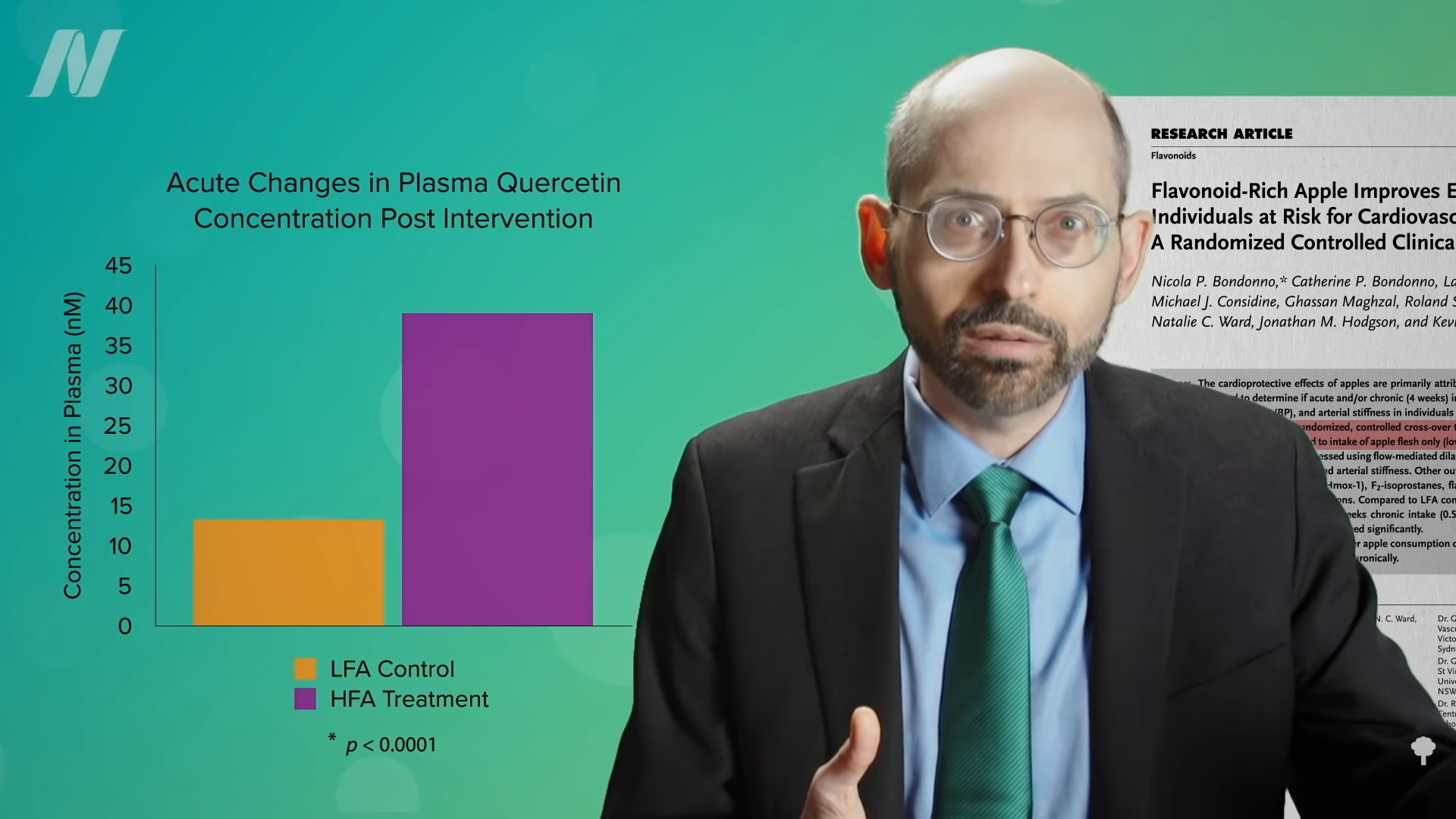

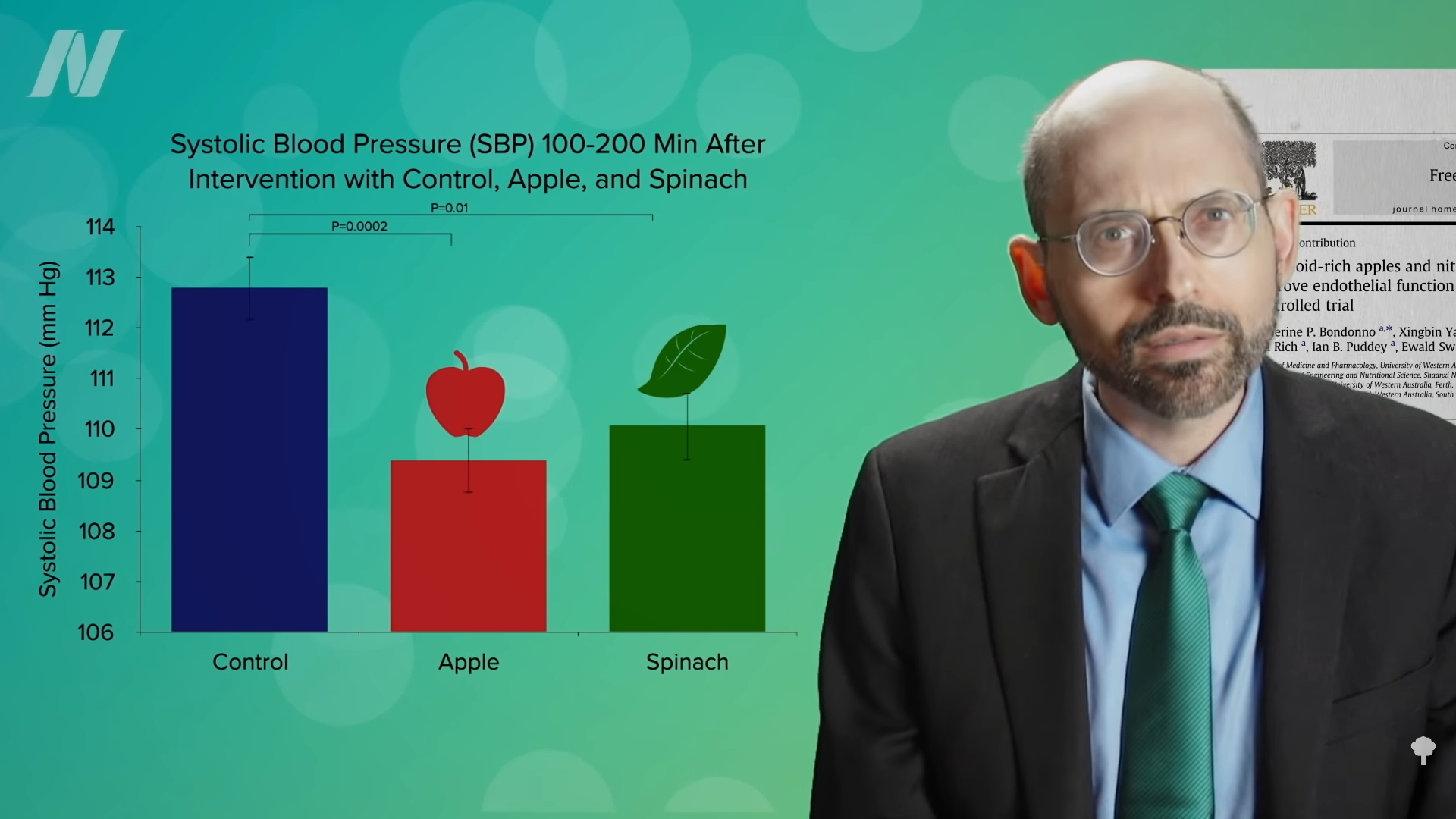

Even compared to spinach? As you can see in the graph below and at 3:14 in my

Even compared to spinach? As you can see in the graph below and at 3:14 in my  What’s nice about these results is that we’re talking about whole foods, not some supplement or extract. So, easily, “this could be translated into a natural and low-cost method of reducing the cardiovascular risk profile of the general population.”

What’s nice about these results is that we’re talking about whole foods, not some supplement or extract. So, easily, “this could be translated into a natural and low-cost method of reducing the cardiovascular risk profile of the general population.”