The extent of risk from bariatric weight-loss surgery may depend on the skill of the surgeon.

After sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the third most common bariatric procedure is a revision to fix a previous bariatric procedure, as you can see below and at 0:16 in my video The Complications of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery.

Up to 25% of bariatric patients have to go back into the operating room for problems caused by their first bariatric surgery. Reoperations are even riskier, with up to 10 times the mortality rate, and there is “no guarantee of success.” Complications include leaks, fistulas, ulcers, strictures, erosions, obstructions, and severe acid reflux.

The extent of risk may depend on the skill of the surgeon. In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, bariatric surgeons voluntarily submitted videos of themselves performing surgery to a panel of their peers for evaluation. Technical proficiency varied widely and was related to the rates of complications, hospital readmissions, reoperations, and death. Patients operated on by less competent surgeons suffered nearly three times the complications and five times the rate of death.

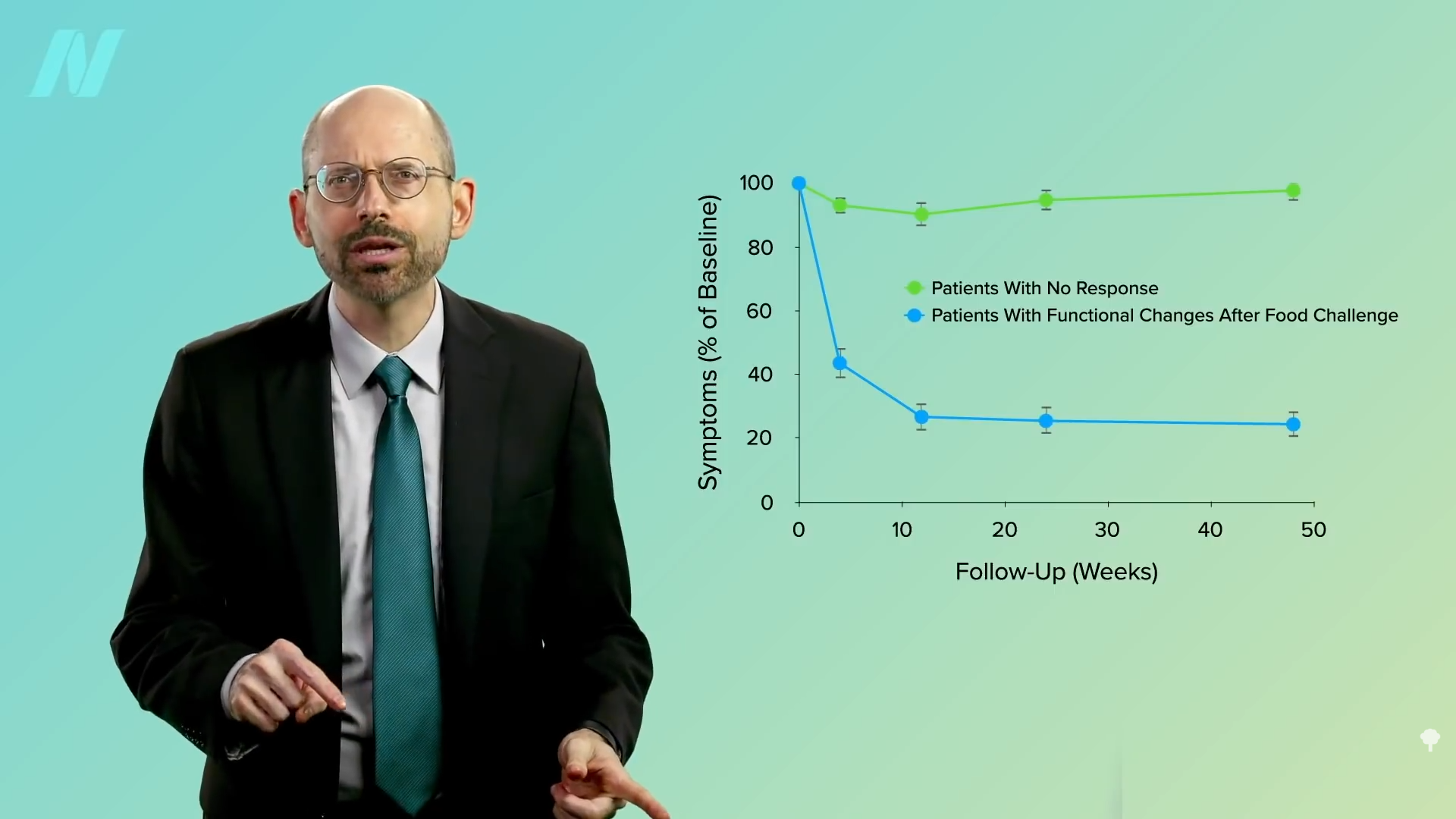

“As with musicians or athletes, some surgeons may simply be more talented than others”—but practice may help make them perfect. Gastric bypass is such a complicated procedure that the learning curve may require 500 cases for a surgeon to master the procedure. Risk for complications appears to plateau after about 500 cases, with the lowest risk found among surgeons who had performed more than 600 bypasses. The odds of not making it out alive may be double under the knife of those who had performed less than 75 compared to more than 450, as seen below and at 1:47 in my video.

So, if you do choose to undergo the operation, I’d recommend asking your surgeon how many procedures they’ve done, as well as choosing an accredited bariatric “Center of Excellence,” where surgical mortality appears to be two to three times lower than non-accredited institutions.

It’s not always the surgeon’s fault, though. In a report entitled “The Dangers of Broccoli,” a surgeon described a case in which a woman went to an all-you-can-eat buffet three months after a gastric bypass operation. She chose really healthy foods—good for her!—but evidently forgot to chew. Her staples ruptured, and she ended up in the emergency room, then the operating room. They opened her up and found “full chunks of broccoli, whole lima beans, and other green leafy vegetables” inside her abdominal cavity. A cautionary tale to be sure, but perhaps one that’s less about chewing food better after surgery than about chewing better foods before surgery—to keep all your internal organs intact in the first place.

Even if the surgical procedure goes perfectly, lifelong nutritional replacement and monitoring are required to avoid vitamin and mineral deficits. We’re talking about more than anemia, osteoporosis, or hair loss. Such deficits can cause full-blown cases of life-threatening deficiencies, such as beriberi, pellagra, kwashiorkor, and nerve damage that can manifest as vision loss years or even decades after surgery in the case of copper deficiency. Tragically, in reported cases of severe deficiency of a B vitamin called thiamine, nearly one in three patients progressed to permanent brain damage before the condition was caught.

The malabsorption of nutrients is intentional for procedures like gastric bypass. By cutting out segments of the intestines, you can successfully impair the absorption of calories—at the expense of impairing the absorption of necessary nutrition. Even people who just undergo restrictive procedures like stomach stapling can be at risk for life-threatening nutrient deficiencies because of persistent vomiting. Vomiting is reported by up to 60% of patients after bariatric surgery due to “inappropriate eating behaviors.” (In other words, trying to eat normally.) The vomiting helps with weight loss, similar to the way a drug for alcoholics called Antabuse can be used to make them so violently ill after a drink that they eventually learn their lesson.

“Dumping syndrome” can work the same way. A large percentage of gastric bypass patients can suffer from abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, bloating, fatigue, or palpitations after eating calorie-rich foods, as they bypass your stomach and dump straight into your intestines. As surgeons describe it, this is a feature, not a bug: “Dumping syndrome is an expected and desired part of the behavior modification caused by gastric bypass surgery; it can deter patients from consuming energy-dense food.

Doctor’s Note

This is the second in a four-part series on bariatric surgery. If you missed the first one, see The Mortality Rate of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery.

Up next: Bariatric Surgery vs. Diet to Reverse Diabetes and How Sustainable Is the Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery?.

My book How Not to Diet is focused exclusively on sustainable weight loss. Check it out from your local library, or pick it up from wherever you get your books. (All proceeds from my books are donated to charity.)

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link