The Paycheck Protection Program opened for business on April 3, 2020.

Not long after, the Small Business Administration’s E-Tran loan processing program crashed. SBA approved about 52,000 loans in fiscal year 2019 under its flagship 7(a) loan guarantee program, 60,000 the year before. As big as those numbers seem, they would be quickly dwarfed by PPP.

Jovita Carranza, who served as SBA’s administrator from January 2020 to January 2021, called 2020 the most extraordinary year in the agency’s history. In that single year, SBA “approved more loans…than it has in all of the years combined since the agency was founded in 1953,” Carranza wrote in SBA’s 2020 Agency Financial Report.

Even so, pushing loans through a sluggish, crash-prone E-Tran would be a perennial problem for the program’s lenders.

For Solomon Lax, CEO of Jersey City-based Revenued, they were the source of one of his most enduring PPP memories. “The most vivid moment was when 5,000 applications hit the system in 10 minutes and the application portal went down,” Lax said. “It was an all-hands-on- deck moment for the company.”

Of course, Revenued, which worked as a partner with Cross River Bank in Fort Lee, New Jersey, managed to get its loans through, as did hundreds of other banks and credit unions that participated in the $800 billion program.

For them, despite controversies that have severely tarnished the program’s reputation in recent months, the PPP experience remains a high point, a time when the industry rallied to support the businesses and communities it serves.

“It is still a source of pride as we positively impacted thousands upon thousands of business owners and the communities they operate in,” Jim Fliss, national SBA manager at Cleveland-based KeyCorp, said. “While PPP is not common office conversation these days, I trust that all who were involved doing the work derive strength from meeting a large challenge head-on.”

A very big deal

It seems safe to include the Paycheck Protection Program within the ranks of the financial services industry’s biggest endeavors in recent years, perhaps among the biggest ever. PPP was intended to support employers and allow them to continue paying employees, especially where coronavirus had forced shutdowns. It came at a time of unprecedented dislocation.

The U.S. gross domestic product plummeted 31% during the second quarter of 2020, giving an indication of the veritable body blow the pandemic delivered to the economy. PPP offered businesses with 500 or few employees fully forgivable loans, provided at least 60% of the proceeds were spent on employee compensation, occupancy, safety equipment, business software and other eligible expenses.

By the time PPP started lending on April 3, the Trump administration had declared a state of emergency and implemented an international travel ban covering more than two dozen countries. Cruise lines halted travel and states and local governments had begun issuing a series of shutdown orders covering schools, theaters, dine-in restaurants, gyms, barber shops and salons, and a host of other businesses. Unemployment, which measured 3.5% at the start of 2020, began rising in March and peaked at 14.7% — a level not seen since before World War II — in April, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Our economy basically shut down,” said Lloyd Doaman, executive director of Carver Community Development Corp., a subset of New York-based Carver Bancorp.

Congress tapped the Treasury Department and SBA to co-administer PPP. Lawmakers implemented PPP as part of 7(a), which had been guaranteeing loans to small businesses since SBA’s creation in 1953. While SBA had acted as a direct lender in its early years, 7(a) had long since evolved into a public-private partnership. Lenders, primarily banks and credit unions, made the loans.

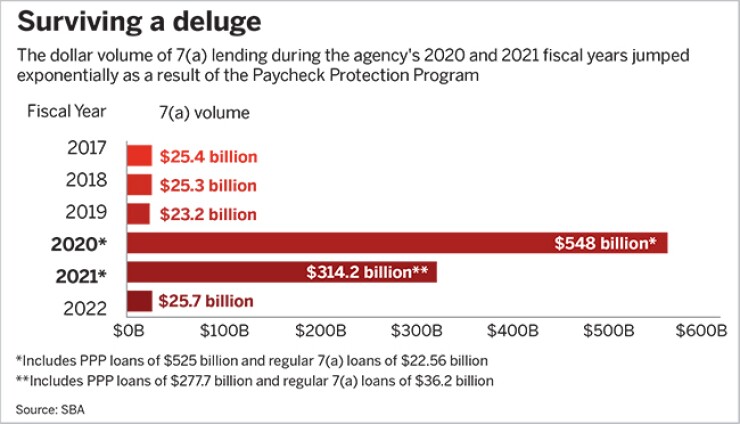

SBA was an obvious choice to manage PPP, given 7(a)’s existing infrastructure, but the move placed banks and credit unions in the path of a hurricane. Congress appropriated $349 billion for PPP loans. It was an enormous number considering 7(a), SBA’s largest lending program, had never handled more than $25.8 billion of loan volume in a single year.

Around the clock

As PPP got up and running, it was clear almost instantly that it wouldn’t take long to dole out the mountain of cash. Most institutions were overwhelmed with applications as soon as they opened their online portals.

At JPMorgan Chase, more than 75,000 prospective borrowers filled out an online form seeking basic application data the first hour it was online.

PPP lenders, nevertheless, distributed the program’s massive initial outlay in just 16 days. Congress provided a fresh $310 billion appropriation to restart the program in May, as well as another $284 billion in January 2021.

Things were never quite as frenzied as during the program’s opening phase in April 2020. The waves of borrowers, combined with E-Tran’s operational woes, forced participating lenders to radically expand working hours. In essence, an industry once joked about for keeping for lax “bankers hours” lurched suddenly to around-the-clock operations.

At many community banks and credit unions, it took the entire staff, from those at the lowest rungs on the ladder to senior managers and CEOs to cope.

“We were working well into the weekends, working late at night,” the $713 million-asset Carver’s Doaman said. CEO Michael Pugh “even rolled up his sleeves. He was working with clients one-on-one. He helped get them to the finish line.”

“People found another gear,” said Ben Parkey, Dallas market president at the $1.1 billion-asset Texas Security Bank in Dallas. “It was inspiring to watch how everyone leaned on each other…We saw individuals grow and develop in a very short period of time out of necessity.”

Due to the pandemic’s rapid onset, PPP never went through the normal legislative and regulatory process most new programs do. It was established without an extended public comment or rulemaking period. Many of the rules and procedures that governed it were disclosed after the program started, then oftentimes adjusted.

“It was a challenging program to take on,” said Ken Michalac, commercial lending manager at the $2.6 billion-asset Lake Trust Credit Union in Brighton, Michigan. “Details were rolled out in an unexpected way, so we had to quickly learn not only how to get the funds to business owners, but also to develop a process for taking in applications.”

The uncertainty created another pressure point for lenders, since frequent changes and additions created widespread confusion.

“What we found was that a lot of our clients needed additional support,” Doaman said. “They needed someone to work closely with them to demystify the process, to help them calculate what their payroll numbers would be, what the final loan amount would be, to just pull together all the documents that they needed.”

The same was true even for bigger banks. At the $190 billion-asset Key, “we received multiple weeks of inquiries — early to late — from countless business owners and our employees on how to best navigate” PPP, Fliss said. “Teams across the bank mobilized at warp speed to setup a new PPP infrastructure, processes and technology.”

Despite well-documented flaws, there remains little doubt, at least in the minds of the bankers and credit union lenders who participated, that PPP was worthwhile. To them, PPP succeeded in achieving its core aim of funneling emergency cash to small businesses reeling from the pandemic, saving millions of jobs in the process.

Most economists agree PPP preserved jobs, though estimates of the number saved vary. A study published in the spring 2022 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives concluded PPP preserved about 2.97 million jobs per week in the spring of 2020.

Nationally, unemployment fell to 11% in June 2020 and was under 7% by the end of the year. GDP, which had declined at a record-setting pace in the second quarter, rebounded to grow at a sizzling 33% pace between July and September 2020.

“PPP mostly worked, despite its flaws,” Keith Leggett, a retired American Bankers Association economist, said. “We were looking into the economic abyss and the program provided a lifeline to main street businesses.

Carver believes its 420 PPP loans helped preserve 5,000 jobs, according to Doaman. Nic Bustle, chief lending officer at U.S. Century Bank in Miami, estimated his institution’s PPP lending saved as many as 17,500 jobs.

“The PPP program, despite its shortcomings, was a lifeline. We felt it was a Dunkirk moment for small business and that everyone we ferried to the other side wasn’t going to make it otherwise,” said Lax, referring to the small coastal town in France where hundreds of thousands of allied forces were evacuated during World War II. “There was real desperation in the voices of the small business owners who had their entire livelihood going to zero before their eyes.”

Changes made

In addition to the 1% interest on their PPP portfolios, banks were paid fees by the government for each loan they made, 5% on credits smaller than $350,000, 3% on those between $350,000 and $2 million, and 1% on deals larger than $2 million.

For PPP lenders, those fees generated substantial income. Northeast Bank in Portland, Maine originated $2 billion in PPP loans on its own and purchased another $11 billion on the secondary market, generating more than $100 million in fee revenue. The $2.8 billion-asset Northeast used its PPP capital to significantly expand its national commercial real estate lending business.

For many banks, though, PPP’s most lasting impact has been the boost it gave to commercial and small-business banking. Case in point: Carver built on its PPP momentum by launching a microloan program.

“We gained some really dynamic relationships and great success stories,” Doaman said. “It’s been pretty effective at helping many of the small businesses continue to pivot and stabilize their operations.”

Texas Security made $264 million in PPP loans in 2020 and 2021. The bank’s loan portfolio, which totaled $403 million at the end of 2019, had grown to $817 million on Dec. 31, 2022 — due in large part to new relationships forged during the pandemic, Parkey said.

PPP “provided us with the perfect stage to demonstrate our ability to roll up our sleeves and show off our work ethic,” Parkey said. “So many of the PPP clients that didn’t have accounts with us before PPP are now full TSB clients.”

Lake Trust Credit Union, too, was able to expand small-business lending, according to Michalak, who said the institution’s PPP clients demonstrated a preference for interacting with people, rather than applying online.

“We were able to show how our hands-on approach to business lending was much more effective,” he said. “Members we work with showed their appreciation for the additional hand-holding that was available to them during that very uncertain time.”

John Reosti

Source link