Although most of those infected with COVID-19 have recovered relatively quickly, a substantial share has not, and remains symptomatic months or even years later, in what is commonly referred to as long COVID. Data on the incidence of long COVID is scarce, but recent Census Bureau data suggest that sixteen million working age Americans suffer from it. The economic costs of long COVID is estimated to be in the trillions. While many with long COVID have dropped out of the labor force because they can no longer work, many others appear to be working despite having disabilities related to the disease. Indeed, there has been an increase of around 1.7 million disabled persons in the U.S. since the pandemic began, and there are close to one million newly disabled workers. These disabled workers can benefit from workplace accommodations to help them remain productive and stay on the job, particularly as the majority deal with fatigue and brain fog, the hallmarks of long COVID.

COVID-19 Was a Disabling Event

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 19 percent of people who have been infected with COVID currently have some form of long COVID. Some of these so-called long-haulers have relatively mild symptoms that may not significantly interfere with daily life, but others have symptoms serious enough that they have become disabled. Indeed, one study has found that the average level of disability among those with long COVID is similar to Crohn’s disease and the long-term consequences of moderately severe traumatic brain injury. It is not clear if, when, and how those with long COVID will recover. A recent study suggests many eventually do, but the disease is still new, and much remains unknown.

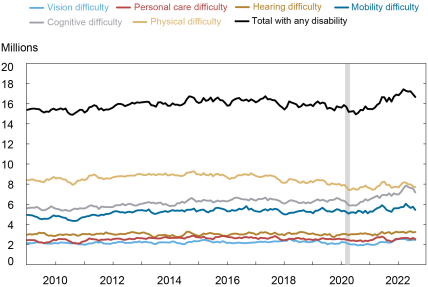

Although data on the disability status of long-haulers is scarce, I examine trends in self-reported disability from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. The chart below plots the number of working age people reporting six different forms of disability: (1) physical difficulty walking or climbing stairs; (2) hearing difficulties; (3) vision difficulties; (4) difficulty concentrating or remembering; (5) difficulty performing basic activities outside the home alone; and (6) a physical or mental health condition that makes it difficult to take care of personal needs. These categories are not mutually exclusive, as respondents can report more than one. This is a self-reported disability status, and is independent of whether a person receives or is qualified to receive any type of disability benefits. The top line in the chart is the number of people reporting any type of disability, and so measures the total number of disabled persons.

Disability Counts Rose Sharply with the Pandemic

Notes: Data are for working-age population, ages 16 to 65. Shading indicates a period designated a recession by the NBER.

There has been a cumulative increase of about 1.7 million working-age people reporting a disability since mid-2020, the point at which disability counts began to reverse course after a years-long decline. Some of this increase may not be directly tied to long COVID (if the stress of the pandemic induced other medical problems, for example). But a recent study found that about a quarter of those with long COVID had altered their employment status or working hours, pointing to a condition serious enough to interfere with work for 4 million people. Thus a rough estimate that just under 2 million people have become disabled primarily due to long COVID seems plausible. Of note, disability counts were generally flat to declining in all categories for several years leading up to the pandemic, suggesting that these figures represent a conservative estimate of working-age adults disabled from long COVID. Somewhat encouragingly, disability counts have come down in recent months, suggesting some with long COVID have recovered to the point where they no longer consider themselves disabled.

One of the hallmarks of long COVID is a type of cognitive impairment called brain fog, which appears to be driving an increase of 1.3 million people reporting difficulties with concentration or memory since mid-2020. These figures suggest that about 75 percent of the disabled with long COVID have cognitive difficulties, in the same ballpark as a recent study which found that cognitive issues were reported by 88 percent of long-haulers. There was also an increase of nearly half a million people reporting vision difficulties, a lesser known but widely reported symptom of long COVID.

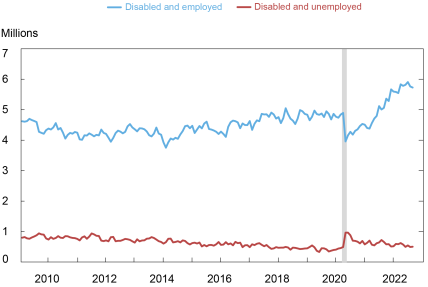

An Influx of Newly Disabled Workers

Some with long COVID appear to be cutting back hours or dropping out of the labor force altogether. However, many appear to be continuing to participate in the labor market, making them a more common feature in the workplace. As shown in the chart below, since February 2020, there has been an increase of about 900,000 disabled working-age persons who are employed, and a small increase in the disabled who are unemployed, resulting in a net increase of close to one million disabled persons in the labor force since the pandemic began.

A Surge in Disabled Workers Since the Pandemic Began

Notes: Data are for working-age population, ages 16 to 65. Shading indicates a period designated a recession by the NBER.

Helping Long-Haulers Remain in the Workplace

Long COVID varies in terms of its symptoms and severity, but its core symptoms include fatigue, brain fog, and muscle/joint pain, making it very similar to another well-known fatiguing illness: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS affects as many as 2.5 million Americans, and is a disease that I personally suffer from. What causes ME/CFS or long COVID is not well known, but like long COVID, ME/CFS often follows a viral infection. The two conditions appear to overlap, as they share much of the same diagnostic criteria and possibly the same etiology (there are no direct biological tests for either condition, both are diagnosed based primarily on reported symptoms). The experience of employers and workers dealing with ME/CFS can be instructive as the labor market experiences an influx of those with long COVID.

Workplace accommodations for those dealing with long COVID may help them remain employed. Long COVID may be considered a disability under the Americans with Disability Act. Private employers with fifteen or more workers, as well as state and local governments, may be required by law to make reasonable accommodations for those with long COVID, though workers may struggle for an accurate diagnosis from their physicians since there are no explicit tests for it. Employers and employees typically work together to determine whether a reasonable accommodation exists that would enable the employee to perform their job. The lessons of ME/CFS suggest that telework and flexible scheduling are two accommodations that can be particularly beneficial for workers dealing with fatigue and brain fog. Such accommodations can help workers with long COVID control their environment, avoid physical exertion around commuting, and take rest breaks as needed, helping them to manage their symptoms and remain productive. But these accommodations may not be reasonable or even feasible for all jobs. Although the distribution of disabled workers across industry sectors is similar to the non-disabled, the disabled are overrepresented in retail, where telecommuting is highly unlikely because workers in this sector are typically required onsite, and underrepresented in business services, where it is more common.

Workers with Long COVID Likely to Remain a Fixture of the Workplace

With millions of Americans suffering from long COVID, employers may well encounter workers disabled from the disease who still want to work. If reasonable workplace accommodations can be made, they may help employers retain such workers—some of whom can be expected to eventually recover. This can be especially important in a tight labor market where workers can be hard to come by. Much remains unknown about the nature and course of recovery from long COVID, and the extent to which future COVID waves will lead to a renewed increase in disability counts. One positive sign is that disability counts have come down in recent months, suggesting that some of those disabled with long COVID have improved significantly. All in all, though, disabled workers with long COVID may well remain a fixture in the workplace for some time to come.

Richard Deitz is an economic research advisor in Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Richard Deitz, “Long COVID Appears to Have Led to a Surge of the Disabled in the Workplace,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 20, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/10/long-covid-appears-to-have-led-to-a-surge-of-the-disabled-in-the-workplace/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Richard Deitz

Source link