I’ve heard it said that there’s no better way to get to know your students than by inviting them to write. I would also add that there’s great value in having students write to develop their literacy skills and that the process of composing is sometimes overlooked.

One of the challenges with writing instruction is that it produces so much work for teachers to grade. As a middle school teacher, I had an average of 120 students. If I had each student write just a little bit each day, this volume of reading (and grading) material added up quickly. Yet, we know from long-standing and more recent research that writing and reading are reciprocal processes. If we don’t have both of these engagements happening frequently, an educator with a critical stance might ask, “What is happening in my students’ literacy development?”

When it comes to authentic development, as well as manageability, peer review is a valuable step. Students need to learn to write for an audience, but it’s also important for them to do the reading work of providing high-level thinking in critique to a peer. It presents another opportunity for them to read with purpose.

The Positives of Peer Review

There are a number of positives for peer review, including the framing of “constructive” criticism as wording from writers and editors that can help the writer construct something new and better, as the name entails. Scathing critiques do little to improve our writing, but neither do “It’s all good” approaches that barely skim the surface.

As a classroom teacher, I share ideas about how to shape and share peer review, including providing focus points and allowing authors the space to share the kind of feedback that would be most helpful to them. I learned this best when I was in graduate school and have since practiced this focused approach with K–12 students.

I emphasize the importance of asking for specific feedback, including identifying areas of strength, as it is an important step and helps students to know what the peer review process is really all about. I also position writing as a process and engage in the vulnerability of demonstrating my own writing to the class. I do not hesitate to lay bare the moments when I might make a mistake or need to think of a better way of saying something.

Specific peer review, both written and verbal, can be useful data that is generated in the moment, and saved for later, to include during conference times (in person or in video meetings) to help further guide the process of composing.

Writing can be a very lonely process. When students are invited to compose drafts, engage in small group or paired discussion, and then incorporate feedback, the classroom process of composing begins to look and feel much more like an authentic way of engaging with writing and creating, rather than simply completing a task for a grade or to prepare for an exam.

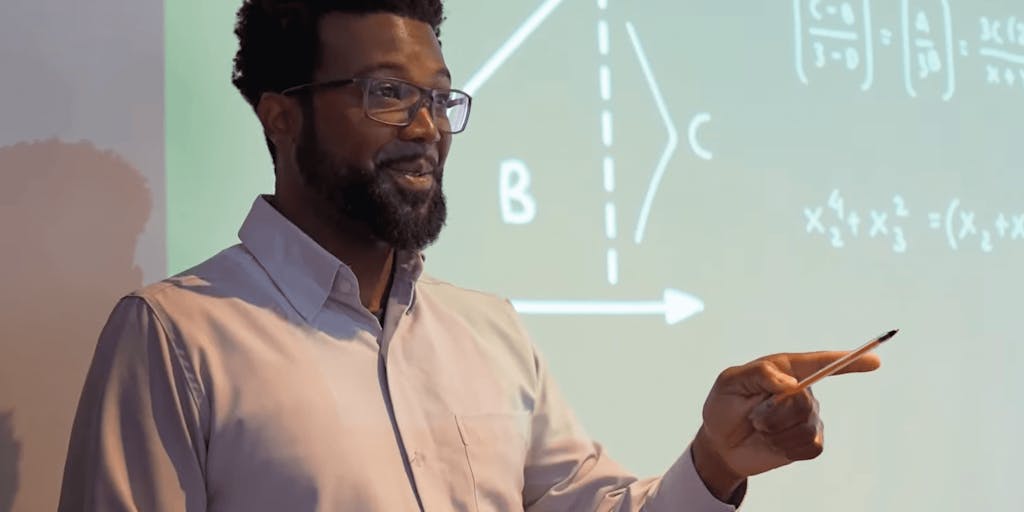

Modeling is key in all of these stages, from the writing itself to the feedback process, and I do not shy away from showing students my writing in development (including notes and comments from editors). Stephen King showed me how to do this so well at the end of his book On Writing, in which the reader gets to glimpse the pages that illustrate that no writer achieves perfection on the first round.

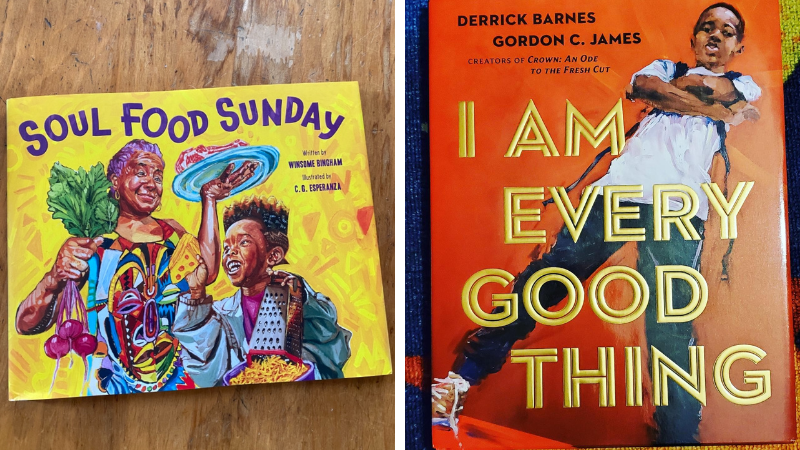

I also freely discuss the times that I have received less-than-helpful feedback—not as a means of commiserating, but in order to show students how to provide feedback in more productive ways. Above all, I attempt to build a culture of revision, which is so vital in writing. Linking to talks, I also share interviews I have done with authors about the many-leveled process of revision. Authors are people too, and the world of authoring is not some exclusive utopia of people whose fingers work magic on keyboards.

We all have a process, and we all benefit from specific feedback. This type of modeling doesn’t require an entire lesson but can be accomplished with a brief series of personal examples coupled with in-the-moment feedback while students are working in small groups. The examples can take only five to 10 minutes of sharing and lead to the kind of specific feedback we’d already want to share with students when conferencing.

Finally, I attempt to celebrate writing as an individual and yet communal exercise in which sharing ideas means writing with others in mind. Kurt Vonnegut famously said that a writer needs to imagine one person they are trying to “speak to” in their composing. Toni Morrison has indicated that we should write the stories that we are looking for.

8 Recommended Strategies for Negotiating Peer Reviews

- Set specific goals for one improvement at a time.Resist the urge to do a complete rewrite when engaging in peer review (or, for teachers, grading).

- Read a wide range of mentor texts, noting specific author moves.

- Connect mentor texts with writing goals.

- Incorporate examples of common errors or challenges in writing for class-wide practice—again, with many examples.

- Embrace multimodal options of composing for students who might find reading and writing to be difficult (including those with particular needs and accommodations).

- Embrace oral language process (i.e., talking through what one will write) as a scaffold to the written word.

- Students may not be in command of the words they want to use just yet.

- Minimize the fear of the blank page by writing in front of and alongside students.