Recent releases by Beyoncé, Lizzo, and even the up-and-coming new act Say She She have incorporated aspects of disco music into their songs. Lizzo’s “About Damn Time,” arguably the song of the year, sounds like an outtake from a Donna Summer or Gloria Gaynor record circa 1979. But there was a time when disco wasn’t so readily embraced. Unlike traditional rock or punk or metal or hip-hop, disco music has had a tumultuous history. It went from an underground scene to conquering the world to being the most reviled music to finally being reassessed and embraced by the world all over again.

The movie’s opening-credit sequence may be the most influential in movie history.

While disco had been bubbling up from the underground, its moment to shine came with the release of the movie and soundtrack to “Saturday Night Fever,” which premiered in December 1977. “Fever” was a crass commercial enterprise. Conceived by music manager and impresario Robert Stigwood and directed by crack journeyman filmmaker John Badham (“Wargames,” “Stakeout”), it was a combination of star vehicle for rising TV teen idol John Travolta, a Norman Lear-ish family sitcom, and an attempt to capitalize on a the then-fading subculture of disco. When you combine all those elements – mix, stir and pour out – you get something unexpectedly artful.

The movie’s opening-credit sequence may be the most influential in movie history. It created a movie star and kicked off a global phenomenon. Beginning with a midday shot of the New York City skyline followed by a subway train heading to a stop, we hear the spangly opening guitar riff to the strut-with-a-purpose “Stayin’ Alive.” We see a pair of shoes walking down a city sidewalk. The camera pans up to reveal Tony Manero (John Travolta), a 19-year-old working-class kid from Bay Ridge. Dressed in dark tight jeans, a red shirt with a gold crucifix around his neck, and leather jacket, Tony is almost always in motion. He moves to the music he hears in his head. His walking is so purposeful that we can hear his footsteps buried deep in the sound mix. We don’t know where he’s headed, but he does. On the rare moments he stops moving – like to grab a couple of slices of pizza – we can sense his pent-up energy.

Performed by the Bee Gees, “Stayin’ Alive” is Tony’s theme song. (“You can tell by the way I use my walk/I’m a woman’s man/No time to talk.”) It is also the theme song to anyone attempting to make it in the big city. The angelic falsettos of The Bee Gees – brothers Barry, Maurice and Robin Gibb – give us and the song a lift — especially when the word “Alive” is stretched out enough to touch Heaven. (The sequence perfectly mirrors the equally indelible opening credits to 1971’s “Shaft.” That one was about empowerment; this one’s about restlessness.)

The album’s success allowed other underground disco artists to penetrate the culture … Following the release of “Saturday Night Fever,” disco was rock.

At the time, disco was mostly relegated to the African-American and gay communities. Occasionally, disco songs managed to break into the mainstream. Songs like “Rock The Boat” or “Boogie Shoes” had enough pop qualities that both the mainstream music press and Top 40 radio didn’t feel compelled to use the word “disco.” That all changed with the soundtrack to “Saturday Night Fever.” The album fueled the movie’s success and the movie fueled the album’s success. Before “Fever,” the Bee Gees were best known as a harmony group that specialized in songs that mixed folk and pop. That all changed after “Fever” broke. For better or worse they will always be considered a disco group. And the album’s success allowed other underground disco artists to penetrate the culture. Performers like Summer, Gaynor and Sylvester became instant household names. In his memoir “Unrequited Infatuations,” Steven Van Zandt writes, “Rock music is dance music.” Following the release of “Fever,” disco was rock.

View of the cover of the soundtrack album from the film ‘Saturday Night Fever,’ 1977. (Blank Archives/Getty Images)

The songs on the album can be broken into three categories. There are the instrumentals (“Manhattan Skyline,” “Salsation”) composed by David Shire. There are other disco songs performed by artists like K.C. and the Sunshine band and The Tramps. But the bulk of the soundtrack is anchored by the Bee Gees. Some songs (like the syncopated shaker “Jive Talkin'”) had been previously released, while others were created specifically for the movie.

A prime example is the dreamy mid-tempo reverie “Night Fever.” We first hear the song as Tony is getting ready to go out, blow-drying his hair, trying on various gold chains and meticulously buttoning his best dress shirt. These actions are intercut with quick images of dancers at the 2001 Odyssey disco club. (Tony can’t wait to get on the dancefloor.) Later, the song is reprised for an extended dance sequence. Tony and his roughhousing friends (who are known as the Faces) have arrived at the club and quickly begin to prowl for action. We’ve watched them crudely shout and antagonize one another and sneak off to the parking lot for some quick anonymous sex. Yet when “Night Fever” begins to play they fall into harmonious step and dance. Late movie critic Gene Siskel chose this sequence as his favorite dance number because it suggested a fevered dream of peace. It shows that if these kids can come together on the dance floor maybe they can find harmony off it. Tellingly, the sequence ends by transitioning to a shot of Tony asleep in his bed.

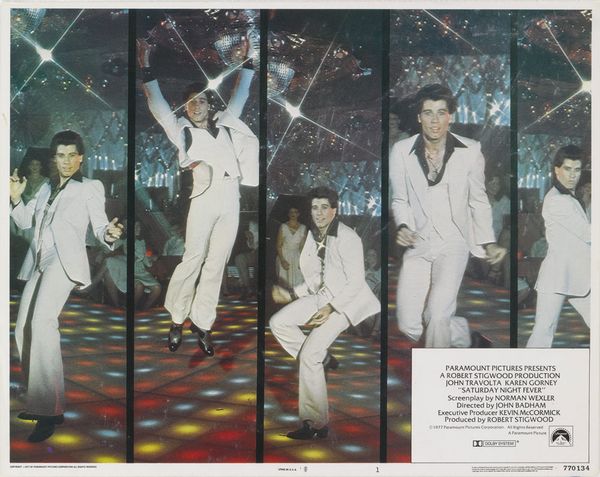

A lobby card for the 1977 US film ‘Saturday Night Fever’, featuring actor and dancer John Travolta. (Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

A lobby card for the 1977 US film ‘Saturday Night Fever’, featuring actor and dancer John Travolta. (Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

Tony is referred to as the “king” whenever he dances. So, when a dance contest is announced — and the top prize is $500 — it is assumed Tony will win. Initially, he teams up with Annette (Donna Pescow), a spunky neighborhood girl who desperately wants to date Tony. They rehearse for the contest, but he’s thinking about changing partners when he sees Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney) dancing at 2001. She’s also from the neighborhood but has made it out and moved to Manhattan. She occasionally returns home to dance — and remind herself why she left. When Tony sees her practicing some solo dance routines at a local dance studio, he tries to pick her up. When she coolly blows him off, his pride won’t allow him to try again. Then, when his brother priest Frank Jr. (Martin Shakar) unexpectedly shows up at home to announce he is leaving the church, Tony begins to reconsider his attitude. In one of the movie’s rare scenes that has no music, Tony and Frank have a heart-to-heart conversation about their assigned roles in the family. Tony says, “Maybe if you ain’t so good, I ain’t so bad.” He is motivated to ask Stephanie again if she’ll be his partner. After some hesitation, she agrees.

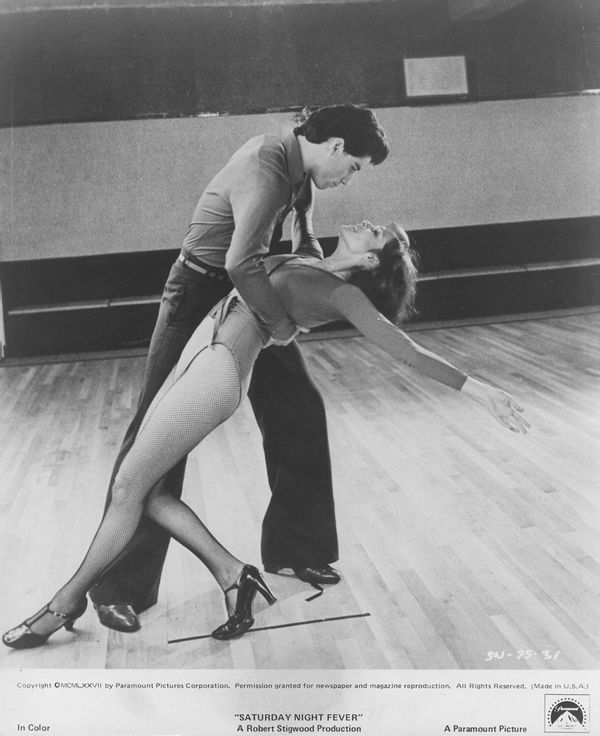

This leads to the movie’s most romantic dance number. Meeting at the local dance studio they try out different versions of the Hustle. When Tony sneaks them into a larger dance studio the number opens up and recalls the great full-frame dance numbers of classic musicals. Scored to Tavares’ version of “More Than a Woman,” Tony and Stephanie come off as a working-class Disco-era version of Astaire and Rogers. (Like Rogers, there are moments when Gorney does everything Travolta does, but backward.) The number climaxes when the two break from their perfectly choreographed moves and hold each other’s hands and spin around and around. They’re like young lovers consummating their partnership. On the night of the dance contest Tony and Stephanie perform to the Bee Gees’ swoony version of “More Than a Woman.” For Tony, who is the product of a world where women are viewed in reductive terms, the song lets us know that he sees Stephanie as someone outside his orbit.

Actor John Travolta in the film ‘Saturday Night Fever’. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Actor John Travolta in the film ‘Saturday Night Fever’. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

If the soundtrack to “Saturday Night Fever” is anchored by the Bee Gees, the movie is anchored by Travolta’s star performance.

Composer David Shire, who is best known for his haunting and tense scores for paranoid thrillers like “The Conversation” (1974) and “All the President’s Men” (1976), shows a completely different side with his work for “Fever.” Tracks like the lush yet ominous “Manhattan Skyline” or the derivative yet catchy “Salsation” blend in beautifully with the rest of the songs. The best instrumental is a version of “How Deep is Your Love,” which plays during a sequence where Tony and Stephanie are driving around and looking at the Brooklyn Bridge. The Bee Gees’ version is heard in the final scene where Tony starts to tentatively mature by asking Stephanie to be his friend. It’s like a love serenade.

And the non-Bee Gees songs do a good job of varying the movie’s tempo just enough so it doesn’t get monotonous. Walter Murphy’s “A Fifth of Beethoven” starts out as a novelty but quickly becomes something more. It connects the past to the present. (Like disco, classical music was the pop music of its day.) “Boogie Shoes,” with its joyous horn blasts and irresistible chorus plays at just the right moment to loosen up the tension. And the Tramps’ “Disco Inferno,” which has become the go-to song whenever anyone wants to make a joke about disco, is actually a James Brown-ish epic that says dancing might be the only thing you can do when the world is burning.

If the soundtrack to “Saturday Night Fever” is anchored by the Bee Gees, the movie is anchored by Travolta’s star performance. Until then, he was just a rising TV star best known as Vinnie Barbarino, the wisecracking member of the Sweathogs gang on “Welcome Back, Kotter.” The character of Tony Manero is far more complex and layered. We are asked to follow him through some dark passages. Tony is a casual racist and sexist, capable of being cruel, and in a shocking scene, attempts to rape Stephanie in the backseat of a car. On paper, the character seems irredeemable. Yet Travolta lets us see that Tony, unlike his meathead buddies, is a thinker. We respond to his street smarts and cockiness, but his startlingly mature eyes tell us his bravado conceals fears and insecurities he is barely capable of articulating.

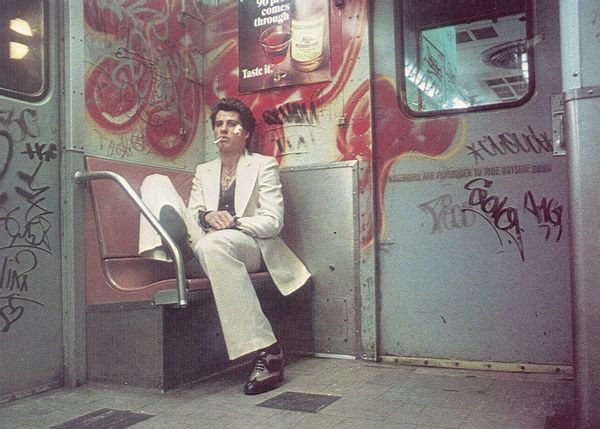

American actor John Travolta sits on a bench inside a subway car painted with graffiti in a still from director John Badham’s film ‘Saturday Night Fever’. (Paramount Pictures/Getty Images)

American actor John Travolta sits on a bench inside a subway car painted with graffiti in a still from director John Badham’s film ‘Saturday Night Fever’. (Paramount Pictures/Getty Images)

But Tony’s saving grace is his dancing. To be clear: Travolta is not a great dancer. Unlike James Cagney or Fred Astaire or Michael Jackson, he lacks the natural talent and grace of those performers. What distinguishes Travolta from them is he is a better actor. He acts like someone who loves to dance. This is most apparent in the movie’s centerpiece dance number: Tony’s dance solo at 2001. The number is filmed in an unbroken full-frame shot in order for us to see that Travolta is doing all the dancing. The song used for the sequence is the disco banger “You Should be Dancing.” With its Mariachi-like horn line and hard-rock guitar playing, the song has a propulsive energy that is matched by Travolta’s aggressive yet fluid dance moves. It’s what made the sequence an instant classic.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Before “Fever,” soundtracks — with few exceptions like “The Sound of Music” (1965), “The Graduate” (1967), “American Graffiti” (1973) — were considered an afterthought. Consumers bought singles, not albums. The exception were the soundtracks for Black-themed movies like “Shaft,” “Superfly” (1972), and “Sparkle” (1976) — which were released months before the movies. The soundtrack to “Fever” used this practice as a blueprint. It created the model for how a soundtrack can be a crucial element to a movie’s success. (Four years later, with the launch of MTV, the synergistic relationship between Hollywood and the music industry would be solidified.) If a movie had a hit single on the soundtrack maybe that would translate to a better box office. Movies as varied as “Footloose” (1984), “Purple Rain” (1984) and “Singles” (1992) all had soundtracks that powered those movies’ success and vice versa.

Yet there was a time when the existence of “Saturday Night Fever” was nearly erased. Following the racist and homophobic “Disco sucks!” movement, disco music all but vanished from radio and the clubs. The 1980s was powered by synth-pop and club music, but disco became a word you didn’t dare speak. Then, in 1994, Quentin Tarantino’s crime epic triptych “Pulp Fiction” pulled off a cinematic sleight-of-hand by killing off its main character in order to resurrect the movie career of John Travolta. The scene where Travolta’s junkie hitman participates in a twist contest fulfilled our desire to see him dance. It was a sight we didn’t know we had been missing. Following the success of “Pulp Fiction,” a long overdue reassessment of “Fever” occurred. The movie was now considered a classic from the Golden Age of 1970s cinema. The Bee Gees were welcomed back. And disco was finally seen for what it truly was: the foundation for all pop music that would follow. And the audience would continue to show how deep their love is for the music. About damn time.

Read more

about this topic