MADISON, Ala. — The team-building exercise was simple. Early this season, coaches at Rocket City, the Angels’ Double-A affiliate, asked each player to step forward and share something personal with the entire squad.

Name a hero in your life, a hardship and a highlight.

Zac Kristofak, a 25-year-old starting pitcher, began internally preparing for his turn. In a way, he’d already spent more than 10 years building toward this moment. And while any cursory Google search of his last name would have turned up the disturbing details from a decade ago, none of his teammates knew the full story.

When Kristofak got up to speak in front of his teammates, there were no nerves. His heart did not pound. His mind did not race. The words tumbled out.

It was Dec. 22, 2012, a cold afternoon in the Atlanta suburbs. Kristofak, then 15, was coming back from baseball practice with his friend. They pulled up to his home to find a large police presence encircling the house.

At first, Kristofak thought there was a fire. But he quickly realized there were no fire trucks on the scene. He jumped out of the car and raced to a police officer, who asked him about his parents.

Just a few hours earlier, Kristofak’s mom, Donna Nations Kristofak, had taken him to baseball practice.

He returned to find his mother’s black Honda Odyssey near her garage, and blood on the ground where EMTs had attempted lifesaving CPR.

It was too late. Zac’s mother, he would later learn, had been murdered by his father.

After Kristofak spoke to the team, “everyone just had a shock to their face,” said Kristofak’s teammate Jack Dashwood. “I think anyone would tell you that Zac Kristofak is one of the toughest dudes that they probably ever met in baseball.”

“This is who I am,” Kristofak said later. “I’m not afraid of who I am.”

Zac (left) and Harrison with Donna Kristofak, during what Zac remembers as a happy and normal childhood. (Courtesy of Zac Kristofak)

In the months leading up to her death, Donna did everything she could to shield her sons, particularly Zac, her youngest, from what her life had become.

It was impossible to hide the fact that she and their father had split up, or that John spent seven months in jail for aggravated stalking. He’d been arrested in March 2012 after chasing Donna around a Walmart parking lot, while a knife sat in his car — days after he’d sent her a threatening note.

But Zac didn’t know those details. The day-to-day, minute-to-minute danger she faced was something Donna tried to protect him from.

Donna, in Zac’s words, would do anything for him and his older brother, Harrison. When the family lost its financial footing after the housing market collapse in 2007, she went back to work. She supported her kids in the midst of economic hardship and her faltering marriage.

And for much of Zac and Harrison’s childhood, John was a seemingly steady and caring husband and father. He’d been married to Donna for 19 years.

John coached Zac and Harrison’s baseball teams. Every Friday night was “boys’ night” — when they’d get a Papa Johns pizza and rent a Blockbuster movie. Zac remembers his family as well-off and happy, as normal as normal gets.

But the financial problems turned into major marital issues. And marital issues turned into a divorce in August 2011. After the divorce, John devolved rapidly. He became furious, bitter and, eventually, violent.

Zac had a fundamental understanding that the once apparently happy relationship had become toxic. He would receive text messages from his father saying nasty things about Donna. But he hadn’t been aware of how dangerous the situation had become.

Starting soon after their divorce, John started sending threatening messages to his ex-wife. He stalked her. He left vulgar signs in front of her yard. He sent notes to other people in her life, claiming she was having multiple affairs. The restraining order against him was of little use.

According to police records, John emailed her at one point, writing, “both kids would rather come to heaven than lose me” and “have you ever been hit by a car going 140 not knowing where it was coming from?,” according to police records. There were other notes threatening her life.

She had an emergency plan with their neighbors, the Kiebooms — a family that included Zac’s best friend and current Nationals infielder, Carter Kieboom. If John ever came to Donna’s home, the kids were supposed to run there.

Two months before her murder, she’d pleaded with a Cobb County judge to keep him in jail. According to an Atlanta Journal Constitution account, she told the judge that a restraining order would not be enough.

“‘May I ask, your honor, that it is on the record that I fear for my life,’” Donna said.

He was released on Oct. 29, 2012. Less than two months later, he shot Donna twice while she sat in her car.

Almost immediately after his capture, John admitted to murdering Donna, according to police records. He explained that he’d been planning the murder for some time.

Donna was usually aware of her surroundings, John told investigators. She had guns, and knew how to use them. He was stalking her neighborhood that day when he saw her driving toward her home. This time, when she pulled into her garage, he said, she didn’t close it immediately. Instead she sat in her car, looking at her phone.

John said he pulled into the driveway, ran to her car, and shot her twice through the car window. She started honking in the hope that Harrison would come out. An onlooker heard him shout “Mom!” as he raced outside to help, arriving in time to see John run back to his car and drive off. The last thing she said to Harrison, according to police records, was to call 9-1-1.

For the next five days, with John still on the run, a police officer stood guard outside the Kiebooms’ home, where Zac was staying, 24 hours a day.

They tracked John down at a Motel 6 in Union City. He spent his days on the run emailing news outlets about Donna. He also attempted to rob a Rite-Aid for Adderall. John claimed that he had planned to commit suicide before his capture, but that police arrested him before he could reach for his gun.

Hours after being taken into custody, he was interviewed by detectives.

At one point during the interrogation, John asked, “Does all this have to come out in the newspaper?”

The investigator said it was between the two of them.

“Good,” John said, “because my kids have been hurt enough.”

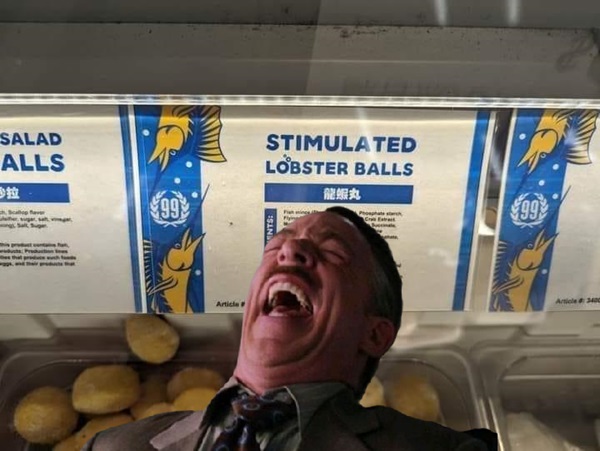

Kristofak, now a pitcher with the Angels’ Double-A team, hopes that his story will be able to help other people going through difficult times. (Patrick Breen for The Athletic)

Kieboom and Kristofak: Two last names that start with K. That’s how Carter Kieboom and Zac first met.

They were 9 years old at baseball tryouts when they were placed next to each other for the 60-yard dash.

In their first encounter, Kristofak told Carter that he would smoke him in the race. And he did.

“Zac’s always had a little bit of an edge to him,” Carter said. “He’s had this aura of confidence that’s always surrounded him. Getting to know him, we played the whole season together, it all made sense. He was going to be a little trash talker.”

Kristofak knows he wouldn’t be where he is now without people like Carter, the Kieboom family and many others who gave him a community when his world had been shattered.

It was Carter’s mother, Lynette Kieboom, who drove Kristofak to the hospital, where he found out his mother had died. The Kieboom family was there. Carter’s father, Alswinn Kieboom, became a father figure.

“He’s like my son,” Alswinn said. “He knows I’m always there for him. And I think the relationship is pretty doggone cool in the sense that neither one of us has to advertise it.”

The people Kristofak is closest to are those who have been there for him. They were all there in that hospital.

Blaine Boyer was a Major League pitcher at the time, but he was also a mentor and close friend to Zac. When they first met, at the gym they both belonged to, Zac was a “punk middle schooler”; they struck up a friendship because Zac was wearing a hat for a team Boyer once played on.

Now here was Boyer, consoling the teenage boy in the hours and days after the most traumatic experience of his life.

“Zac, to this day, has a room at our house,” Boyer said. “It’s his room. He would stay with us. You talk about rallying people around a little. It was from high school seniors and juniors to all the parents to his grandparents to just all the community. Just rallying around this kid, who was so unbelievably loved.”

Following that awful December 2012 day, Zac moved in with the Kiebooms temporarily. Christmas morning came three days after his mother’s murder. His father was still on the run. The hours, Zac said, were split between numbness and a sharp, painful grief.

But on that morning, everyone showed up. Zac said that they received more than 300 presents. People came in to deliver them and pay their respects.

Zac went back to playing baseball just two months after his mom’s death. About 10 days after the murder, his grandmother, Helen Pullium, moved to the area from Alabama and rented a home nearby so that Zac could finish high school there. At a time when everything was uncertain, everyone was trying to tiptoe around him, he could rely on baseball to stay the same.

“He allowed people into his life, and it just made him that much better,” Carter Kieboom said.

As a reliever for Georgia, Kristofak — here pitching against LSU in 2017 — reached the NCAA tournament twice before the Angels selected him in the 2019 draft. (John Korduner / Icon Sportswire via AP Images)

Zac didn’t go far for college. He attended the University of Georgia, and helped the Bulldogs reach the NCAA Tournament twice in three years, operating as both a starter and a closer at various points.

He kept in touch with the people who were there for him. And everyone was thrilled when Kristofak was drafted by the Angels in 2019, in the 14th round.

Simply reaching Rocket City, playing in Double A, is an accomplishment. The first few years of Kristofak’s pro career were tough. COVID deprived him, and many others, of competition in 2020. The year after, he struggled, posting a 6.14 ERA in 44 innings out of the bullpen. He left that year not knowing if he’d get another shot.

Since then, Kristofak has steadily risen through the Angels system. The front office was so impressed with him that he was in consideration for a major-league call-up earlier this season before an elbow injury shelved him in June. He watches and follows every Angels game. He wants to be a part of it.

Making the majors someday is about more than fulfilling his own dream. It’s about changing the narrative of his family’s name.

“I’ll get to write my own story,” Kristofak said this summer, sitting on a restaurant patio overlooking his apartment complex in Alabama. “I think that what I want to do, more than anything in life, is rewrite the Kristofak name.”

Kristofak wants to be known as a baseball player. He wants to be known for the community that lifted him up after his mother’s murder — not for the man locked up in Hays State Prison for the rest of his life.

“I know that if my mom were here right now,” Kristofak said, “she would be really proud of my brother and I.”

While Kristofak is now comfortable discussing his mother’s murder, the rest of his family still isn’t. Harrison declined to talk for this story, as did Zac’s other family members. But Harrison and Zac talk weekly, and regularly visit each other.

“He’s the only person that really understands what I’m going through. So there’s …” Zac said, before pausing to try and figure out the right words. “It’s hard to explain, honestly.

“There’s a mutual understanding that no matter what, we will always have each other’s backs. I could go my whole life without saying it, and we would both know it.”

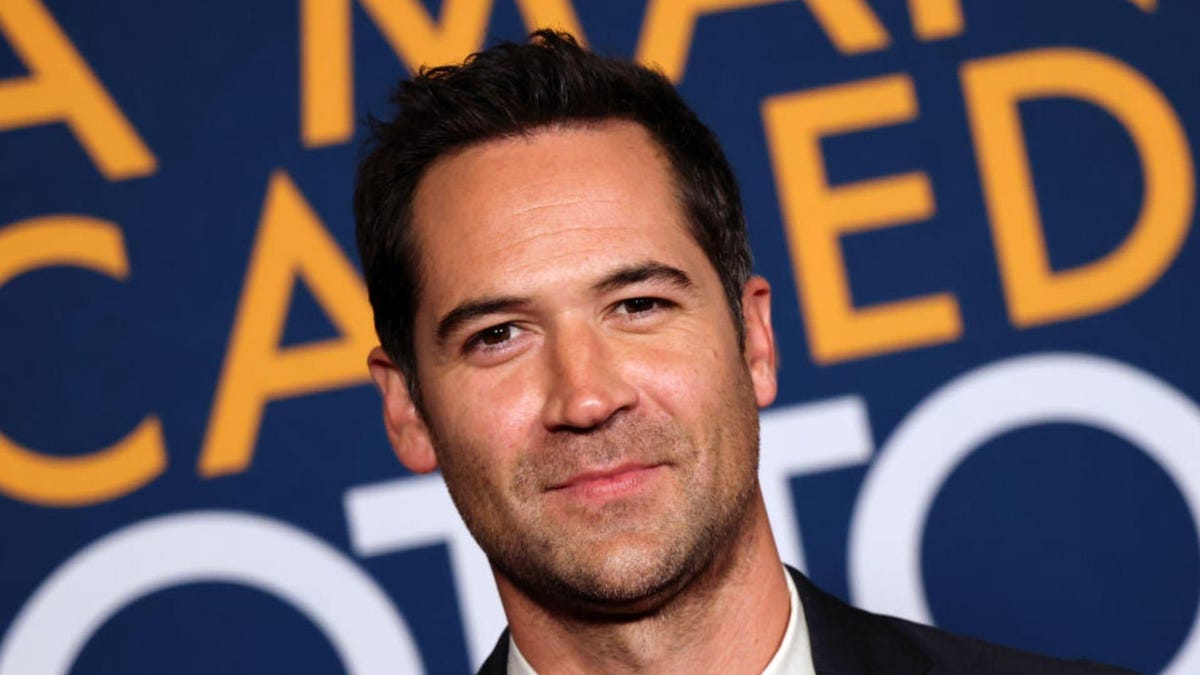

One of Kristofak’s most vivid early memories is watching a Braves game with his mother, and telling her that he wanted to be an MLB player. (Patrick Breen for The Athletic)

When Kristofak finished sharing his story with his teammates earlier this season, Dashwood, one of Kristofak’s closest friends on the team, approached him. He was the emotional one, telling Kristofak that sharing his story that way revealed his character.

“He gained an unbelievable amount of respect — on top of the respect everybody already has for him,” said Angels prospect Kenyon Yovan, Kristofak’s Double-A roommate. “Everyone is always there for him.”

Kristofak wants to be an open book. He believes his story might help people get through their own painful moments.

“I think he understands his purpose a little better than most of us,” said Boyer. “I think Zac truly wants to help people that are hurting.

“His scars are what make him incredible.”

It’s not always easy for Kristofak after games. He sees players celebrating with their parents. On Mothers Day, Fathers Day.

Rocket City would have been a perfect place for him to play. It’s so close to where he grew up. Instead, he’s constantly reminded that his father is a two-hour drive away, serving a life sentence after pleading guilty to malice murder and possession of a firearm during commission of a felony.

Kristofak has never visited his father in prison, and while he says he has forgiven him, the anger and frustration are still palpable.

“It’s not fair,”Kristofak said. “Even though he’ll never walk a sidewalk again or never be a member of society ever again. He gets to breathe. And she doesn’t. That’s not fair.”

So much of the coverage of the case focused on the breaking news — the shocking murder and the fugitive capture.

It never focused on Donna, and what she meant to her children. That’s how Kristofak remembers her. He acknowledged that he’s scared to grow older and have those memories fade. But he plans to have a family of his own one day. He wants to be an incredible father. And he wants to have kids who will learn about, and appreciate, the grandmother they will never meet.

The day he turned 18, he memorialized her with a large “D.N.K.” tattoo on his left wrist.

One of Kristofak’s most vivid early memories of Donna is sitting next to her, watching an Atlanta Braves game. He was 5 years old, watching Chipper Jones play against the Florida Marlins, when he turned to her and said: “I want to be a Major League Baseball player.”

Making the big leagues certainly won’t change what happened. But reaching that level — putting on an Angels uniform with Kristofak sewn on the back — will mean something that perhaps only Kristofak and his mother could fully understand.

“I can put the light into it,” Kristofak said of his story. “Because there is light.”

(Top image: Samuel Richardson / The Athletic; Photos: Patrick Breen for The Athletic)

The New York Times

Source link