BOSTON — With the stroke of a pen, Gov. Maura Healey is moving to wipe away the prior pot convictions of hundreds of thousands of Massachusetts residents.

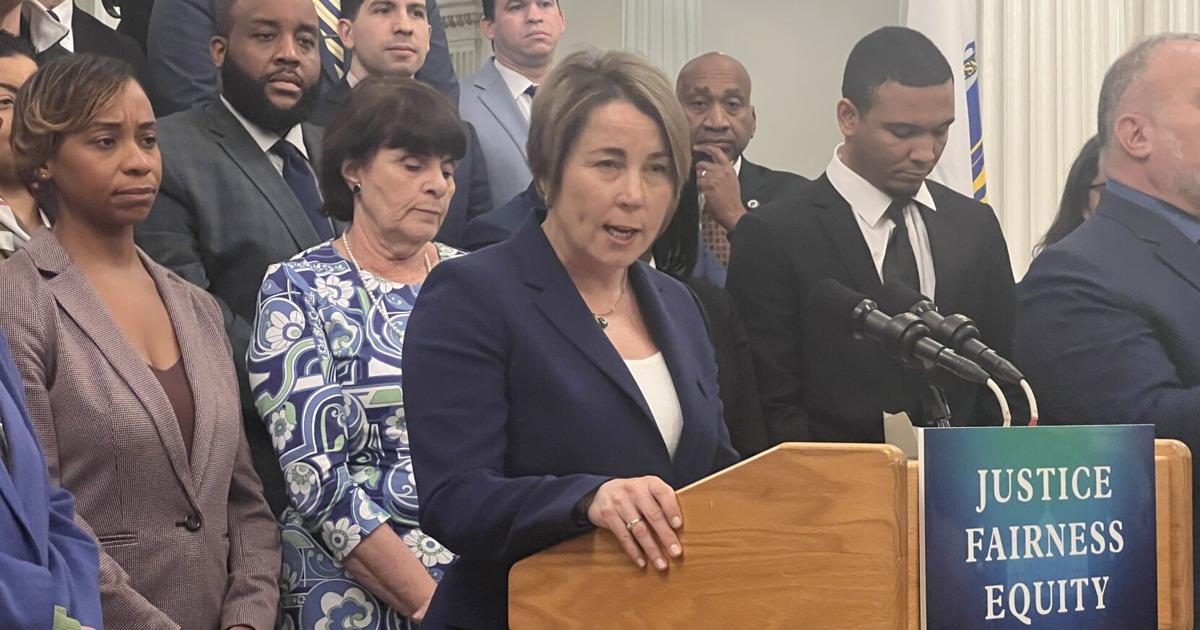

On Wednesday, Healey signed a “first-in-the-nation” executive order that, if approved by the Governor’s Council, would grant a blanket pardon to those with previous misdemeanor convictions for possession of marijuana, which has been legal for more than seven years.

Healey, who estimates the pardon will impact “hundreds of thousands” of people, says those with misdemeanor pot charges on their records from prelegalization days face restricted access to jobs, housing and education.

“The reason we’re doing this is simple, justice requires it,” the first-term Democrat told reporters at a briefing. “Massachusetts decriminalized possession for personal use back in 2008, legalized it in 2016, yet thousands of people are still living with convictions on their records.”

If Healey’s order is approved by the council, those with previous convictions wouldn’t need to apply for pardons — which would be done automatically — but would be able to request a “certificate” from the state verifying the pardon.

The pardons won’t apply to convictions after March 13, and would exclude charges such as possession of marijuana with intent to distribute, distribution, trafficking, or operating a motor vehicle under the influence or convictions outside the state, including federal court, the Healey administration said.

Attorney General Andrea Campbell, the state’s top law enforcement officer, was among those who praised the move. She said it will improve racial justice, with data showing that blacks and other minorities have been “disproportionately” charged with marijuana possession in the state prior to legalization.

“These pardons will transform the lives of thousands, remove barriers allowing them to live with economic dignity, and right past wrongs and stigma that these individuals have faced,” she said in remarks.

Voters legalized marijuana more than seven years ago, but people previously arrested with the drug are still being haunted by past convictions.

A 2008 ballot question made possessing an ounce or less of marijuana a civil offense, punishable by a $100 fine. Four years later, voters approved its medical use.

Then, in 2016, nearly 54% of voters at the ballot box approved legalized recreational marijuana.

Marijuana advocates say voters have made clear over the years that possession of small amounts should not be illegal, and people with old convictions should get a second chance.

Other states where recreational marijuana is legal have taken similar steps to seal or expunge criminal records en masse.

California wiped away past marijuana convictions under a bill signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2018. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed an expungement bill in 2019 that allowed an estimated 150,000 people to have previous convictions sealed.

In 2022, President Biden issued a presidential proclamation pardoning many federal offenses for simple marijuana possession offenses. Biden has expanded that pardon to include more offenses and has called for a review of the classification of marijuana, which remains illegal under federal law.

But clearing records of past convictions, even in places where pot is legal, remains controversial. Washington state, which legalized pot in 2012, wrangled for several years to pass a pot expungement bill amid opposition from prosecutors.

In Massachusetts, law enforcement officials and even some lawmakers have pushed back on efforts to retroactively wipe away previous convictions.

Proposals to grant blanket pardons for pot convictions have been filed in the past several sessions only to languish due to lack of support.

A 2018 law allowed Massachusetts residents with previous convictions for offenses that are no longer illegal — including marijuana possession — to have those records expunged from their records. But advocates say since then few people have benefited from the changes.

In some cases, judges refuse to sign off on expungement of previous marijuana possession convictions, even if the individual’s records have been sealed.

Under state law, expungement requests must be deemed to be “in the interest of justice” but the interpretation of what that might be is generally left up to judges.

Pauline Quirion, a lawyer and director of the criminal records sealing project at Greater Boston Legal Services, said anyone who undergoes state Criminal Offender Record Information checks for housing or work can be turned down if they have marijuana charges in their past.

“In practice, any criminal record, no matter how old or how minor, creates barriers to jobs and other opportunities,” she said. “Pardons especially matter where record sealing simply is not enough because an employer or occupational licensor is granted access to the record by state law.”

Christian M. Wade covers the Massachusetts Statehouse for North of Boston Media Group’s newspapers and websites. Email him at [email protected].

By Christian M. Wade | Statehouse Reporter

Source link