What was once considered a fairly common jellyfish fossil is actually an ancient sea anemone, a new study reveals.

Artwork by Julius CsotonyiAn artist’s depiction of the ancient sea anenomes that were mistaken for jellyfish.

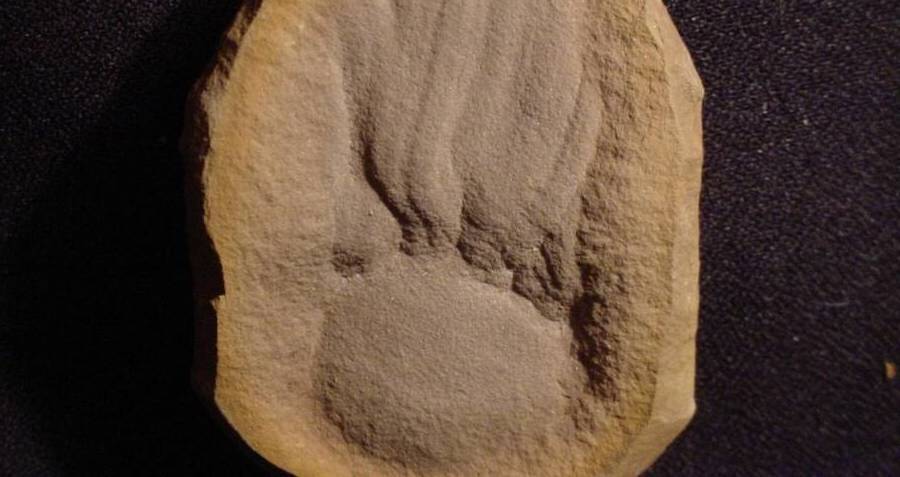

Mazon Creek in northern Illinois is a world-famous Lagerstätte, a term coined by paleontologists to describe sites with exceptionally preserved fossils. The most common type of fossil found at Mazon Creek is referred to as “the blob,” which in 1979 was determined by Bradley University professor Merrill Foster to be a jellyfish fossil. He assigned it the name Essexella asherae.

A new study, however, found that “blobs” aren’t jellyfish at all — they’re sea anemones. For the past several decades, scientists have just been looking at the fossils upside down.

“I’ve always looked at these jellyfish fossils and I’ve thought, ‘That doesn’t look right to me,’” study lead author Roy Plotnick, University of Illinois Chicago professor emeritus of earth and environmental sciences, told Live Science. “I said, ‘Wait a minute; that looks like the foot of a sea anemone.’”

To explore this hunch further, Plotnick got in contact with study co-authors James Hagadorn, an expert on unusual fossil preservation at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, and Graham Young, curator of geology and paleontology at the Manitoba Museum in Canada. Together, they reexamined an array of E. asherae fossils from the Field Museum in Chicago, as well as several specimens from private collections.

“These fossils are better preserved than Twinkies after an apocalypse. In part that’s because many of them burrowed into the seafloor as they were being buried by a stormy avalanche of mud,” Hagadorn said in a statement.

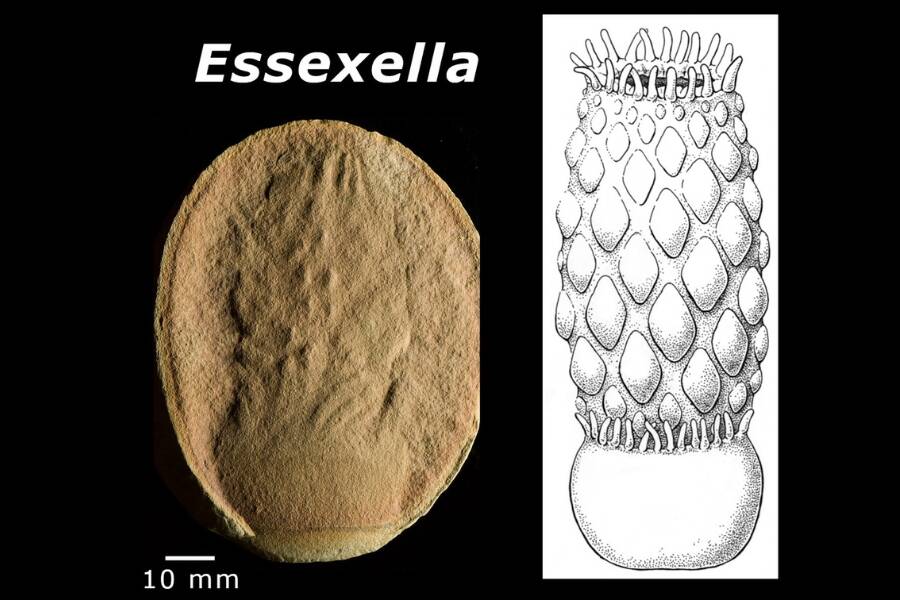

The Mazon Creek fossil beds formed 309 million years ago during the Carboniferous period (358.9 million to 298.9 million years ago). It was a warm, wet period of history where many of Earth’s modern landmasses were still covered by the ocean.

The Mazon Creek fossil beds exist in an area that was once an estuary, a point where a freshwater river flowed into the ocean. The river would have carried a fair amount of silt with it, meaning any plants or animals that died in the estuary were quickly buried in sediment.

As a result, paleontologists have been able to collect impeccably well-preserved fossils, even those of soft-bodied creatures like jellyfish and sea anemones which normally don’t fossilize well.

“Although most of these fossils are preserved as decomposing blobs that look like a piece of used gum on the sidewalk, some specimens are so superbly preserved that we can even see the muscles that the anemones used to bend and contract their bodies,” Young said.

When Foster first described the fossils in 1979, he noted that the “jellyfish” had a distinct feature not found in living jellyfish: a tough “curtain” that hung from E. asherae’s bell like a skirt, enclosing its tentacles and giving it a barrel-like shape.

But what Foster had described as a “tough curtain” was actually the anemone’s barrel-shaped body.

“It quickly became obvious that not only it wasn’t a jellyfish, but turned upside down it was clearly an anemone, probably one that burrowed into the seafloor,” Plotnick said. “The ‘bell’ was actually an expanded muscular foot used to wiggle the anemone into the seafloor.”

To be fair to Foster, sea anemone fossils are incredibly rare. Their squishy bodies don’t tend to have parts that are easily fossilized, so in theory, it was more likely for blob fossils to be jellyfish.

In fact, blob fossils are so common, Plotnick noted, that many people who found them either discarded them or sold them for a few dollars at local flea markets.

Evidently, thousands of “rare” sea anemone fossils have been hiding in plain sight for nearly 50 years.

Papers in PalaeontologyAn Essexella fossil dating back 309 million years alongside an illustration of what it looked like in life.

Foster had also noted that an ancient snail species was often fossilized along with E. asherae. He believed these snails to be parasitic predators feeding on the living jellies, but the new study, published in the journal Papers in Palaeontology, suggests that the snails were actually scavengers feeding on the dead sea anemones lying on the ocean floor.

The wide variations in how these fossils were preserved, then, can be attributed to the different lengths of time dead anemones sat on the sea floor before being buried.

“When jellies like Essexella wash up onto the beach, they become a veritable beachside buffet, being snacked on by snails and other creatures like we see in this fossil deposit,” Young said.

What’s more, the new study revealed that blob fossils hadn’t only been miscategorized as a species — they had been placed in the entirely wrong taxonomic order. Jellyfish fall under the order Semaeostomeae, but sea anemones are part of the Actiniaria order. This is a fundamental difference, yet the discovery was surprisingly serendipitous.

“Anemones are basically flipped jellyfish. This study demonstrates how a simple shift of a mental image can lead to new ideas and interpretations,” Plotnick said.

For other fascinating fossils, read about when scientists discovered that this 558 million-year-old fossil was actually the world’s oldest known animal. Then, read about the nine-year-old who tripped over a rock — that turned out to be a fossil from the human “missing link.“

Austin Harvey

Source link