Bazaar News

Flying Machines, Gunpowder, And The Philosopher’s Stone: The Story Of Medieval ‘Wizard’ Roger Bacon

[ad_1]

Medieval philosopher Roger Bacon was said to have predicted numerous inventions hundreds of years before they were created and may have even discovered the formula for the philosopher’s stone.

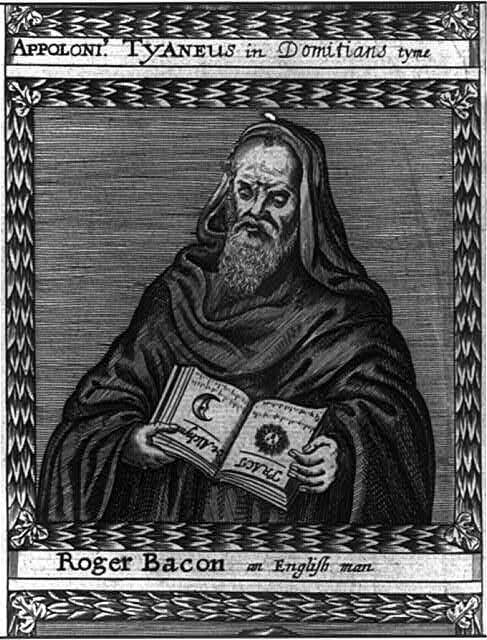

Today, Roger Bacon is regarded as a forward-thinking genius in both scientific and philosophical circles. However, most people living in 13th-century England alongside him thought he was a sorcerer — if not a fool.

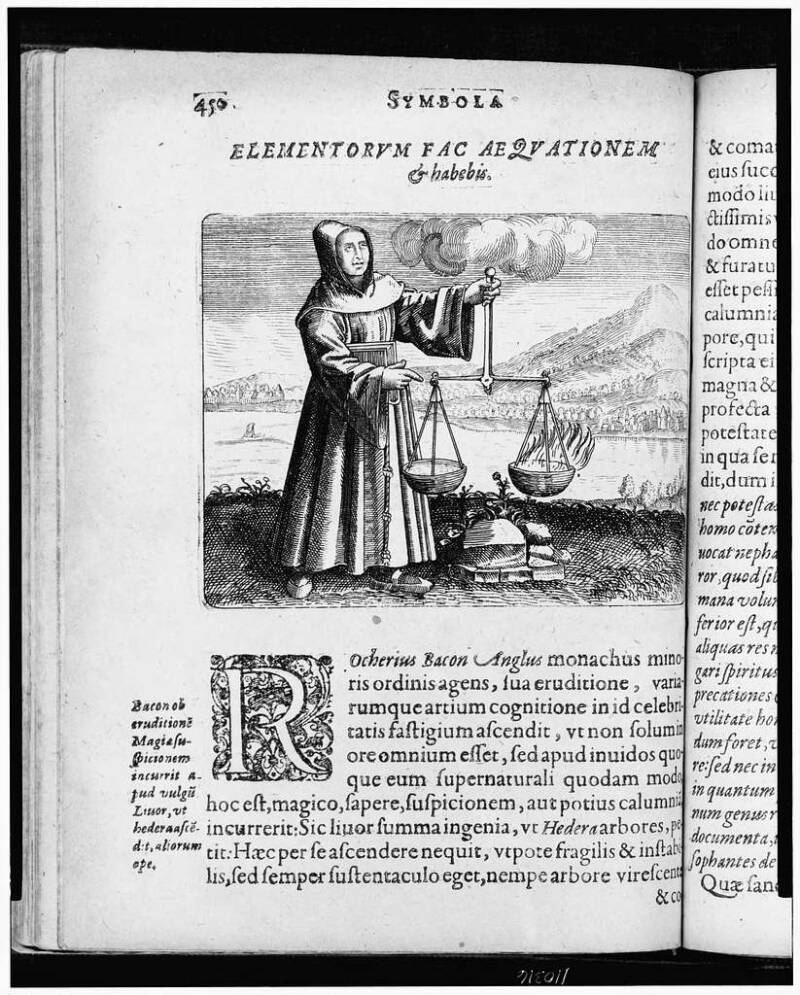

Public DomainRoger Bacon in his observatory at Merton College, Oxford.

Bacon is perhaps best known for being the first European to document the recipe for gunpowder. However, he also worked as a philosopher who reformed the educational practices of the time. And he made waves during his lifetime for documenting another controversial subject: alchemy.

As a scholar, Bacon believed that alchemy was the unifying science. Under it, mankind could achieve the ultimate wisdom. However, as a Catholic friar, he also held that alchemy was the key to religious salvation — even though the church condemned alchemy as highly suspicious at the time, according to ThoughtCo.

Bacon died around 1292, having spent his life combining science and religion in unprecedented ways. His work received plenty of criticism and even led to his incarceration in 1277 — but today, he’s remembered as one of the top scholars of the 13th century.

How Roger Bacon’s Early Education Shaped His Future Work

Roger Bacon grew up knowing he wanted to be an educator. He earned a degree from Oxford University in England, where he became an expert on the works of Aristotle. In the 1240s, he started lecturing at the University of Paris.

While in France, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, he lectured on Aristotelian logic, Latin grammar, and the mathematical aspects of astronomy and music.

Wikimedia Commons

Roger Bacon observing the stars.

Around 1247, he left Paris, and his whereabouts for the next 10 years remain unknown. Historians believe he likely lived in France or near Oxford, working as a private scholar. He studied Greek and Arabic works on optics (the physiology of eyesight and the eye and brain anatomy responsible for it), a subject that Bacon later had added to the medieval university curriculum.

He also started carrying out experiments that helped shape the scientific method as we know it today.

Bacon’s Impact On The Modern Scientific Method

By the 12th century, a decent portion of Aristotle’s writings had been unavailable to the west for over a thousand years, as Arabs had seized the original scrolls during their Mediterranean takeover. Europeans rediscovered the philosopher’s writings during this time and translated them into Latin.

Roger Bacon studied Aristotle while at Oxford and greatly admired the famed thinker.

He began carrying out chemistry experiments based on Aristotle’s writings, but the tests weren’t turning out as expected. He found that Aristotle, the time-honored great thinker, was actually wrong about many things. Bacon had to discard years of work because of this discovery.

The incorrect parts of Aristotle’s writings made Bacon hesitant to trust anything. Annoyed, he struggled to find a way to make knowledge trustworthy — a way to logically prove the truth.

PicrylBacon conducting an experiment.

At this time, people believed that a logical argument alone could prove the truth. Aristotle provided theories that were logically correct, so people assumed they were truthful. However, Bacon’s experiments suggested otherwise.

Bacon concluded that there were four stumbling blocks to the truth: reliance on faulty authority, popular opinions, personal bias or vanity, and reliance on rational arguments.

While Bacon believed that what he saw in his laboratory was correct, he also knew that he needed to find a way to be absolutely sure. Other people needed to conduct the exact same experiments. This would eliminate any personal bias on his part.

What was duplicated in the lab could then be considered truth. Hence, the birth of the scientific method. While Bacon isn’t credited with actually inventing the scientific method, he is seen as a vital forefather who added inductive reasoning to the process.

Some of the projects Bacon worked on weren’t quite as readily accepted into the scientific community, however.

Roger Bacon And The Philosopher’s Stone

During the course of his studies, Roger Bacon became familiar with the study of alchemy and its relation to nature and medicine. He also studied Hermeticism — a set of philosophical beliefs that unified elements of Jewish and Christian mysticism with ancient Egyptian beliefs. It was popular with both Muslim scholars and European intellectuals during Bacon’s lifetime.

Around 1257, Roger Bacon became a friar in the Catholic Franciscan Order. He was initially attracted to it because some scholars he admired were also members. The Franciscans encouraged deeper learning in philosophical, theological, and scientific subjects.

However, his involvement in the order also meant obeying a rule that prohibited friars from publishing any works without explicit approval. This meant a forced break from scholarly pursuits. But in the mid-1260s, Bacon decided he wanted to return to Oxford.

He reached out to those higher in the Catholic Church for permission to do so and eventually gained the attention of Pope Clement IV. Due to a misunderstanding that Bacon had already written his request, the pope asked to read it.

Bacon had to start writing in a hurry.

Picryl

Bacon studying an alchemy book.

His aim was to reform Christian education at the university level. He insisted that Christians needed to learn about science — and alchemy. He believed that anyone who could create alchemy’s mythical “philosopher’s stone” could attain divine truths.

His written plea, or Opus Majus, contained seven sections. Fearing this work would get lost in transit, he wrote a second summary — and even a third as a backup. Together, these books contained about a million words and took a year to write on parchment with a quill pen.

In his book Roger Bacon: The First Scientist, Brian Clegg called this process “one of the most remarkable single efforts of literary productivity”.

Bacon sent these writings to a very receptive Pope Clement IV around 1267. Unfortunately, Clement died in 1268.

Nine years later, the University of Paris banned the teaching of certain philosophies, and records show that Bacon was perhaps imprisoned or placed under house arrest for violation of this rule.

Eventually, however, Bacon did return to Oxford. He is presumed to have spent the remainder of his life there until his death around 1292.

Roger Bacon’s Scientific And Philosophical Legacy

After Roger Bacon’s death, those who feared his ideas immediately put the rest of the manuscripts he left behind under lock and key. They are believed to have since been eaten by insects.

His large catalog of written works numbers close to 101. Most of these are on grammar, mathematics, general physics, optics, astronomy, chemistry, magic, and alchemy.

damiavos/FlickrA statue of Roger Bacon at Oxford University.

A couple of hundred years after Bacon’s death, people regarded him as a possessor of forbidden knowledge — or even a wizard. However, 16th-century philosophers attempted to clear his name and reputation, hailing him as a scientific pioneer. By the 19th century, William Whewell stated in his History of the Inductive Sciences: “Roger Bacon’s works are not only so far beyond his age in the knowledge which they contain, but so different from the temper of the times… that it is difficult to conceive how such a character could then exist”.

Indeed, it’s said that Bacon predicted things such as modern cars, airplanes, and submarines, though the works some of these predictions are based on could be misattributed. Nevertheless, Roger Bacon is remembered today as an avid seeker of universal truths.

After reading about medieval philosopher Roger Bacon, learn 37 facts about the Middle Ages that will make you thankful you live in modern times. Then, check out these 33 beautiful illustrations that merge art and science from 19th-century naturalist Ernst Haeckel.

[ad_2]

Erin Kelly

Source link