Petroleum is a critical input in modern economies. Besides its uses as fuel, petroleum is essential for making chemicals, plastics, other synthetic materials and asphalt. It is also used in electricity generation.

Because of this importance, it is not surprising that major oil supply disruptions in the United States have often been associated with recessions. This article explains one technique for quantifying the transmission of oil supply shocks to real economic activity, specifically employment in the manufacturing sector.

The Oil Market and the Macroeconomy

The figure below plots the dollar price of a barrel of oil in the U.S. over the past 56 years, with recession periods shaded in gray. Sharp rises in oil prices have frequently preceded recessions. For example, the recession that occurred from November 1973 to March 1975 was preceded by the 1973 oil embargo initiated by members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Price of Oil (U.S. Dollars Per Barrel), 1966-2022

The 1980 U.S. recession followed the 1979 oil shock, when reduced supply occurred alongside increased prices. In February 1980, the price of a barrel of oil increased by about 133% from one year earlier. More recently, some economists have argued that the doubling in oil prices between June 2007 and June 2008 intensified the 2007-09 recession, which is mainly associated with the housing downturn and financial crisis.

On the other hand, oil price increases are not always associated with economic downturns. If oil supply factors are stable, then increased oil demand—perhaps due to an improving global economy and economic outlook—can drive up oil prices. For example, the sustained period of economic growth in the U.S. and many other countries between 2002 and 2007 occurred along with sustained oil price growth.

To summarize, reductions in oil supply will increase oil prices and reduce employment and economic growth. In addition, increased economic growth will raise demand for oil and increase oil prices. Economists want to know the effect of oil supply changes on economic activity. Uncovering that effect requires the researcher to disentangle how much of a price movement is supply versus demand driven.

Uncovering the Effects of Oil Supply and Oil Demand Shocks

The following figure, a classic supply-demand diagram, describes the supply and demand for world oil. The horizontal axis marks quantity (e.g., millions of barrels of oil per month) and the vertical axis marks price (e.g., dollars per barrel of crude oil).

Supply and Demand for Oil

The supply curve plots the combined quantity supplied by sellers of oil at various prices. At a higher price, producers will be willing to sell more. Hence, the supply curve slopes upward. The demand curve plots the combined quantity demanded by buyers of oil at various prices. At a higher price, people and firms will try to economize on their use, and buyers will purchase less. Therefore, the demand curve slopes downward.

The market is in equilibrium when the quantity supplied equals quantity demanded. This occurs at the point where the supply curve intersects the demand curve. The market price of a barrel of oil can be read on the horizontal axis at the intersection of the two curves.

It is important to note that economists can’t directly observe the demand or supply curve in any market—oil or otherwise. That is, it is hard to tell exactly how much oil producers would supply or consumers would demand at different prices. Economists usually observe the actual quantity and price that occur in the economy and how these change over time as the unobservable demand and supply curves shift.

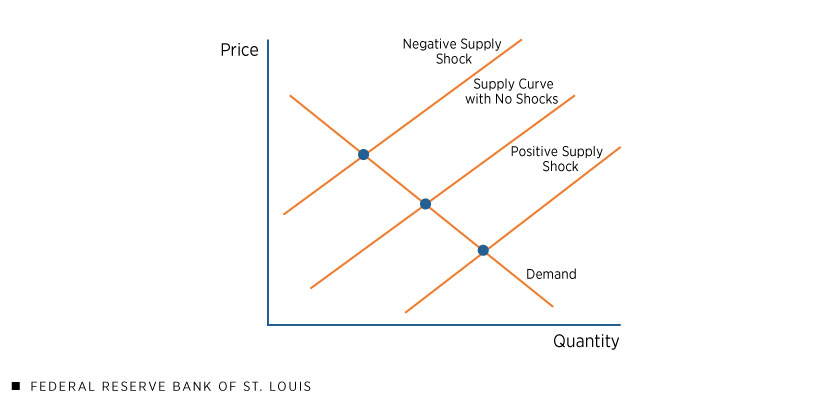

Using the actual price and quantity combinations observed in the economy can, however, be informative about supply and demand curves. The figure below shows three supply curves. The middle curve represents the supply curve in the absence of external shocks to the oil market; the supply curve on the right reflects conditions following a positive supply shock (such as a new discovery of oil); and the supply curve on the left reflects conditions following a negative supply shock (such as a disruption caused by civil unrest in an oil-producing country).

Supply and Demand for Oil: Supply Shocks

If an economist knows that all shocks to the oil market are supply driven (i.e., reflect movements in the supply curve), the observed equilibrium prices and quantities will trace out the demand curve as seen in the preceding figure. Likewise, if all shocks are demand driven, prices and quantities will trace out the supply curve.

Identifying Changes in the Oil Supply Curve

In the real world, both supply and demand curves move constantly and unpredictably. Unlike the very large shocks of the 1970s, economists often find it difficult to untangle which factor, or combination of factors, is moving observed prices and quantities.

In a recent article in the American Economic Review, Northwestern University economist Diego R. Känzig presented a useful way to extract supply shocks from data. Känzig explains that much of the world’s supply of oil is set by Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) members in regular meetings held by member nations. He looked at the change in oil price around tight windows before and after meetings over time.

Although demand and other supply factors may be shifting supply and demand curves most of the time, by focusing only on price changes within these small periods of time, Känzig makes a compelling case that changes in quantity and prices around these tight windows are driven by supply shocks (both positive and negative).

Using these observations, he showed that negative news about supply coming out of these meetings increases oil prices immediately and leads to a gradual fall in oil production. Of course, these shocks are a very small fraction of the many factors moving oil prices, but their value lies in the fact that isolating them allows economists to measure the impact of a fairly pure supply shock on other variables.

The Effect of Oil Supply Shocks on Manufacturing Employment

My recent working paper with Timothy Conley of Western University and Mahdi Ebsim of New York University extends Känzig’s analysis by studying the effects of his oil price shocks on U.S. employment. We focus specifically on manufacturing employment because this sector is particularly reliant on oil. Moreover, we focus only on contractionary supply shocks and exclude expansionary shocks because research has shown that the former has a much greater effect on the macroeconomy.

In response to a 20% increase in the price of oil driven by a contractionary supply shock, we estimated that manufacturing employment fell by 1% over an 18-month horizon. Over a two-year horizon, the effect was slightly smaller, with manufacturing employment falling by 0.8%.

We view this employment effect as relatively small. One potential reason is that we estimated the response over a relatively recent period: January 1991 to January 2017. Oil has likely diminished in its importance for the U.S. economy relative to the 1970s because the U.S. has become dominated by the service sector and other sources of energy have gained prominence.

Notes

- The spot price per barrel for West Texas Intermediate crude oil increased from $15.85 in February 1979 to $37 in February 1980.

- For an in-depth look at how the rise in oil prices impacted the 2007-09 recession, see “Oil Prices and the Economic Recession of 2007-08” by James Hamilton and the Brookings working paper “Disentangling the Channels of the 2007-2009 Recession” by James Stock and Mark W. Watson.

- This article, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Supply News: Evidence from OPEC Announcements,” appeared in the April 2021 issue of the American Economic Review.

- See our 2022 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis working paper, “The Sine Aggregatio Approach to Applied Macro.”