In late April, China‘s state media added to the anticipation surrounding the country’s third aircraft carrier, the Fujian, by teasing new capabilities and next-generation technologies that will be studied by friends and adversaries alike.

The warship, named for the province directly opposite Taiwan, has successfully completed mooring trials since its launch into the Yangtze River last June at the state-owned Jiangnan Shipyard north of downtown Shanghai, according to Chinese state broadcaster CCTV. It is widely expected to undergo its first sea trial later this year.

The new carrier’s future role in the Chinese navy remains the subject of much speculation, but it has already been a boon to Beijing’s flag-waving national prestige. The United States and its allies say it is a part of the largest military buildup in peacetime history, while analysts say it is a natural progression of China’s sea power.

At 1,036 feet, the Fujian is comparable in overall length to the U.S. Navy’s Nimitz-class and latest Gerald R. Ford-class supercarriers, which each displace 100,000 tons versus the 80,000 tons of their newest Chinese counterpart. However, more significantly for lengthy deployments at sea, the American ships use mature nuclear propulsion technology instead of diesel-powered engines.

China’s second domestically built aircraft carrier could enter service alongside a number of “new-type carrier-based aircraft,” CCTV said in its program on the eve of the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s 74th anniversary on April 23. It showed mock-ups of new fast jets variants, helicopters, drones, as well as an airborne early warning and control aircraft, an essential but long-missing piece of the military branch’s decade-long carrier operations.

Li Tang/VCG via Getty Images

The introduction of electromagnetic technology for both the launch and recovery of aircraft is the most closely examined of all features previewed for the Fujian, which would become the first non-U.S. carrier to utilize something akin to the electromagnetic aircraft launch system, or EMALS, of the Gerald R. Ford class.

Little is known about China’s electromagnetic system, which would replace the “ski-jump” ramp on its existing warships of Soviet design, the Liaoning and the Shandong, and altogether skip the steam-powered catapults used on American carriers for over half a century.

Advantages of EMALS are said to include speed, safety, and the ability to launch a wider range of heavier and lighter aircraft, but it is not yet clear how the Fujian‘s conventional power generation capability will be reconciled with the high energy needs of the electromagnetic system. The three catapults on its flight deck have remained under cover from the start.

Baby Steps

China’s aircraft carrier program may be in its infancy, but it plans to operate four ships by 2030. Not all will reach what the Pentagon calls full operational capacity before that deadline. The USS Gerald R. Ford, commissioned in 2017, achieved initial operational capacity, or basic combat readiness, in December 2021 and began its first deployment last October.

“Like the contemporary warship programs in the PLA Navy, the carrier program follows an incremental approach. Initial batches are built in small numbers, but they are not complete test beds; they also report for operational purposes. Later they will be used as the basis for improved follow-on versions before they settle on an agreed version which they mass-produce,” said Collin Koh, a research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

China has designated its three carriers the Type 001, Type 002 and Type 003. The next ship, an iteration of the Fujian, is expected to be the first of the Type 004 class.

“Given its limitations and the weaknesses that it is very much aware of, the PLA is trying to seek foreign models to learn from, especially the U.S. military, which, on the one hand, is a conceivable adversary one day. At the same time, the PLA admires the way the U.S. military operates, but it will not be easy for the PLA to gain insights on these activities,” Koh told Newsweek.

Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Jacob Mattingly/U.S. Navy

The U.S. Navy‘s 11 carrier strike groups, largely self-contained and spread across the globe, might be the gold standard for China’s naval forces to emulate, but Beijing may lack the means and the motive to maintain such a large carrier fleet.

“The U.S. Navy is a global navy and has been for many decades, and it benefits from a global network of allies and partners that are willing to provide access. By comparison, getting a Chinese carrier to project its presence beyond its immediate waters is more demanding and challenging. There are only a few friendly ports that China could possibly call into, and that they would consider reliable,” said Koh.

One lesson the Chinese navy appears to have learned from the Americans is to use the Liaoning and the Shandong to “show the flag,” he said, after the U.S. deployed carrier battle groups in or near the waters separating China and Taiwan during the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1995-1996.

“These two carriers are used not just to conduct training, but to show force whenever there is tension around Taiwan or when the U.S. conducts exercises in the South China Sea,” Koh said.

Current and former defense officials in Taiwan have publicly stated that they expect China’s carriers to frequent the Philippine Sea in the Western Pacific as a training ground for their navy pilots, who will gain the kind of experience that cannot be replicated on land.

“China’s vast seas” mean three carriers aren’t enough, the recent CCTV program said. “Therefore, new aircraft carriers are bound to be built in the future.”

By the next decade, PLA Navy carriers may yet match, or outmatch, their U.S. Navy peers in size or on a technical level, but analysts are less certain when China will be able to catch up with America’s lead in intangible know-how, refined through decades of peacetime training and wartime operations, including with interoperable allies, under a fundamentally different military culture.

To be sure, regional stakeholders in the Asia-Pacific won’t be standing still as its carrier fleet grows; each new breakthrough is likely to justify a capability to counteract it. And governments in the West are all but certain to further tighten the screw on Beijing’s attempts to take shortcuts with outside help.

A Decisive Domain

China dominates modern shipbuilding in the 21st century, producing more warships than anyone else, with excess capacity to spare. As of 2021, its global market share in commercial shipbuilding was 44.20 percent, ahead of South Korea’s 32.39 percent and Japan’s 17.65 percent, according to the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

China is thought to have surpassed America in total warship numbers in around 2015, although the U.S. Navy still leads in overall tonnage thanks in large part to its carrier fleet. The PLA Navy has approximately 340 “battle force ships,” a definition that includes submarines, the Pentagon said last November. It projected the number would rise to 400 by 2025 and 440 by 2030.

Over the past 20 years, the U.S. Navy has maintained between 270-300 deployable warships. Its latest 30-year shipbuilding plan could result in a force level of 319 by the middle of the century, excluding any surface and underwater unmanned vehicles, the Congressional Research Service said in a report last month.

The underlying thinking behind China’s maritime strategy isn’t easy for outsiders to glean, but top leaders including President Xi Jinping have emphasized the importance of the naval component in the PLA’s stated modernization goals. Beijing’s otherwise opaque decision-making process can also be assessed by what it builds and buys.

The PLA Navy, like the rest of China’s armed forces, was historically structured, trained and equipped by the Soviet Union, and grew up on an accompanying doctrine, said Tom Shugart, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security in Washington. D.C.

Its future will be “much more oceanic,” he told Newsweek. “They’re already a blue-water navy. Now it’s a question of becoming a world-class blue-water navy.”

“By every measure but sheer naval tonnage—they’ve already got the numbers—China is the world’s premier maritime power. There’s no reason to think they aren’t going to naturally develop the transoceanic naval power to go with it. And unless you have a huge network of naval bases overseas, it’s going to mean carriers,” Shugart said.

Beijing’s long-term focus, he said, will likely be on the Indian Ocean, where critical shipping lanes connect China to raw materials from Africa, commercial markets in Europe, and oil and gas from the Middle East.

BILL WECHTER/AFP via Getty Images

Over 80 percent of world trade was delivered by ship in 2022, UNCTAD figures showed. Up to two-thirds of maritime cargo was handled in Asia, and one-third of seaborne trade went through the South China Sea via the Strait of Malacca, which links the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Like its neighbors in Asia, China remains heavily dependent on maritime transport for the import and export of goods, and for the energy that powers its economy. Saudi Arabia was its top supplier of crude oil last year, and Qatar was among its main sources of liquefied natural gas.

Sea Control

The realities of market forces and the unparalleled value of maritime routes mean China’s leaders are animated by the same concerns about economic security as their Western counterparts, Emma Salisbury, an associate fellow at the U.K.-based Council on Geostrategy, told Newsweek.

“When it comes to global interests, most states will have a pretty similar outlook. They want to keep their sea lines of communication open and make sure they have the possibility to influence activities in their periphery and in their region,” Salisbury said.

China’s experience in what it terms the “far seas” began in 2008 with an anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden. The PLA Navy’s 43rd task force arrived off the Horn of Africa this past February to begin the country’s 15th year escorting merchant ships past Somalia’s turbulent coastline.

In 2017, the Chinese navy began operating a support base in Djibouti, alongside other foreign militaries including the U.S. Navy, to guard approaches to and from the Suez Canal. The pier at the facility, which also has a runway, was expanded in 2021 to accommodate large warships, including future carriers.

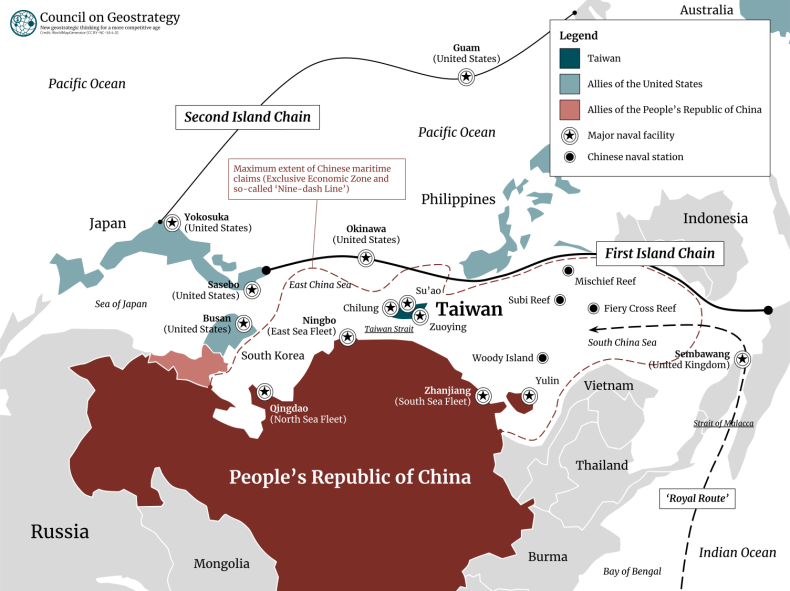

Council on Geostrategy/WorldMapGenerator

“China’s main focus at the moment is regional. It’s within the first island chain and coming out into the South China Sea and the Philippine Sea to deter third-party intervention in their immediate region, most obviously focused on Taiwan,” said Salisbury.

“It may want naval assets in strategic chokepoints around the world; efforts to get military bases in other countries will assist them in moving towards that kind of strategy, but it won’t be possible for quite a while. Global power projection in the naval sense is dominated by the U.S. and will be for a long time,” she said.

China intends to displace America in the postwar international order and would first seek control of Taiwan, said Ian Easton, a senior director at the Project 2049 Institute in Arlington, Virginia, and author of The Final Struggle: Inside China’s Global Strategy.

China claims the island as its own, but Taiwan’s democratic society has for decades rejected the notion of one day being ruled from Beijing. It is a potential flashpoint that is expected to drawn in a U.S.-led response.

“One of the first steps for Beijing is to conquer Taiwan, which occupies a central geostrategic position in the heart of East Asia and the Western Pacific. Taiwan stands astride the world’s most important sea, air, and information passageways, but its government is diplomatically isolated and uniquely vulnerable to attack,” Easton told Newsweek.

“China’s naval buildup is stunning and, so far, has yet to be met by a countervailing U.S. submarine and shipbuilding program,” he said. “It would be disastrous for the U.S. to allow China to get into a position where it could hold our maritime trade lines at risk.”

Do you have a tip on a world news story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about China? Let us know via [email protected].