For 31 months, I languished on Rikers Island, waiting for my day in court. Many people have heard of Rikers Island and its cruel dysfunction. And some know that roughly 90% of the people confined there are Black — like me — or Latinx. Fewer people know that Rikers bears the name of Richard Riker, who enslaved Black people, boasted that he could “arrest and send any Black to the South,” and used his power as a judge to classify Black people as “fugitive slaves.”

When I was transported in restraints from Rikers to the towering courthouse in lower Manhattan, I was confronted by a white prosecutor and a white judge. I looked up at the venire — the panel of people from which the jury is drawn — and that too was filled with white faces. Among the dozens of people who would potentially decide my culpability and fate, only five were Black.

My future would lie in the hands of those selected to be on the jury. Studies demonstrate that non-representative juries convict at higher rates and on higher counts, and make more mistakes, especially when the defendant is Black. I was representing myself, facing a maximum sentence of life imprisonment for a crime I did not commit.

At the beginning of every trial, to winnow down that pool of dozens to a jury of 12, the prosecution and the defense exercise what are called “peremptory strikes,” and remove jurors that they consider to be undesirable. While there are few limits placed on peremptory strikes, one prohibition is of constitutional and ethical concern: prospective jurors may not be struck on the basis of race.

Despite that clear command, the Supreme Court’s seminal case, Batson v. Kentucky (1986), created a framework that has made it nearly impossible for a defendant to prove that a prosecutor excluded prospective jurors on the basis of race. At step one, the defense must present evidence of racial discrimination, which typically requires that they show significant racial disparities between who is struck and who is seated. At step two, the prosecutor must explain the reason for their strikes on “race-neutral” grounds, which has meant that they can say almost anything.

Courts in New York and around the country routinely bless preposterous justifications, including a prosecutor (in a separate case) disapproving of three Black prospective jurors’ “demeanors” (New York); not liking a Black prospective juror’s “eye contact” (Arkansas); removing a Black prospective juror who “wore a beret one day and a sequined cap the next” (Mississippi); excluding a Black prospective juror who was from a “bad ZIP code” (Maryland); had a “strong personality” (Oklahoma); and had a “nervous appearance” (Louisiana).

In his prescient Batson concurrence, Justice Thurgood Marshall, who founded the NAACP Legal Defense Fund before joining the court, predicted the limitations of this framework: “If such easily generated explanations are sufficient to discharge the prosecutor’s obligation to justify his strikes on nonracial grounds, then the protection erected by the court today may be illusory.” And as the Equal Justice Initiative explained in a recent report, “The Batson decision did not deter prosecutors from engaging in illegal race-based peremptory strikes so much as it incentivized them to find ways to keep striking Black jurors without triggering a Batson objection.” Prosecutors have been so successful at evading Batson that, in recent years, exonerations from death row are about as common as an appellate finding that a prosecutor struck a prospective juror on the basis of race.

With that backdrop, Melanie Soberal, the white prosecutor in my case, used her peremptory strikes to exclude four of the five Black prospective jurors. Only one Black person remained. I did not need formal legal training to know this was objectionable, so I stood up and objected: “My objection, Your Honor, is predicated on the fact that there [were] only five African-Americans in this panel, and that, as an African-American defendant sitting opposite the prosecutor [is] suggesting something. I think it conveys something to the rest of the panel . . . I can see it. And it becomes conspicuous after the jury was composed, that it omitted African-Americans . . . with the exception of only one.”

What had been past became prologue. Soberal gave a series of false explanations rooted in pernicious racial stereotypes — including her baseless argument that seated white prospective jurors were more intelligent than an identically situated Black prospective juror — which the court rubber stamped with approval. In other words, my Batson objection was denied. In one of the most diverse cities in the world, only one Black person sat on my jury. I felt terrified and alone.

Even though I was not tried by a jury of my peers, I was acquitted of the most serious charge. I was, however, convicted of three non-violent misdemeanors, including “resisting arrest” and “obstructing governmental administration,” which as I know from this experience are charges associated with police acting abusively against the people in their custody.

The Daily News Flash

Weekdays

Catch up on the day’s top five stories every weekday afternoon.

Despite being relieved that I would not be spending the rest of my life in prison, I felt strongly about appealing the remaining convictions because my trial was so tainted by racial discrimination. The odds of the courts providing a remedy, though, were quite low. In the last decade leading up to my appeal, I could count on one hand the number of Batson reversals issued by appellate courts in New York. The New York State Appellate Divisions not only unblinkingly reject Batson claims, but they are also often hostile to lawyers who raise them. Only the most obvious cases of intentional racial discrimination are engaged with in a meaningful way.

After reviewing the record and hearing oral argument, the Appellate Division unanimously determined that my case was one of those rare and obvious cases. In a signed and published decision reversing my conviction, the court held that the prosecutor intentionally discriminated on the basis of race during the jury selection process. In so doing, the court concluded that the prosecutor had lied to the court, providing multiple false “race-neutral” reasons that were pretext for racial discrimination, including one that was “grounded in a stereotype of dubious validity” for which “there is no evidence that the prospective juror possessed the qualities supposedly inherent in that stereotype.”

Implicit in the court’s finding is that Soberal had not only violated my rights under the state and federal constitutions but had violated the rights of that Black prospective juror. As the United States Supreme Court has explained, “Other than voting, serving on a jury is the most substantial opportunity that most citizens have to participate in the democratic process.” Similar to voter suppression efforts, prosecutors who engage in racial discrimination in the jury selection process are participating in jury suppression.

In 2020, after George Floyd was murdered in public view by a white police officer, the chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals commissioned a report to investigate the state of equal justice in New York’s court system. The report’s conclusions, made by a special advisor who had spent much of his career in law enforcement, were troubling but not surprising: “There is a second-class system of justice for people of color in New York State.” The special advisor’s report stressed that “[t]his is a moment that demands a strong and pronounced rededication to equal justice under law.”

To imbue those words with meaning, we must tackle racial discrimination in the jury selection process. Holding prosecutors accountable through the rules of professional responsibility is a critical place to start, especially since prosecutors are so often cloaked in impunity through absolute immunity. A prosecutor cannot be described in the rules of professional responsibility as a “minister of justice” and at the same time discriminate against the person they are prosecuting and the prospective jurors who dutifully arrive to court.

AccountabilityNY, including attorneys from Civil Rights Corps and law professors, filed a series of ethics complaints against prosecutors based on Batson violations, including in my case. The rule of law, and those of professional responsibility, require accountability.

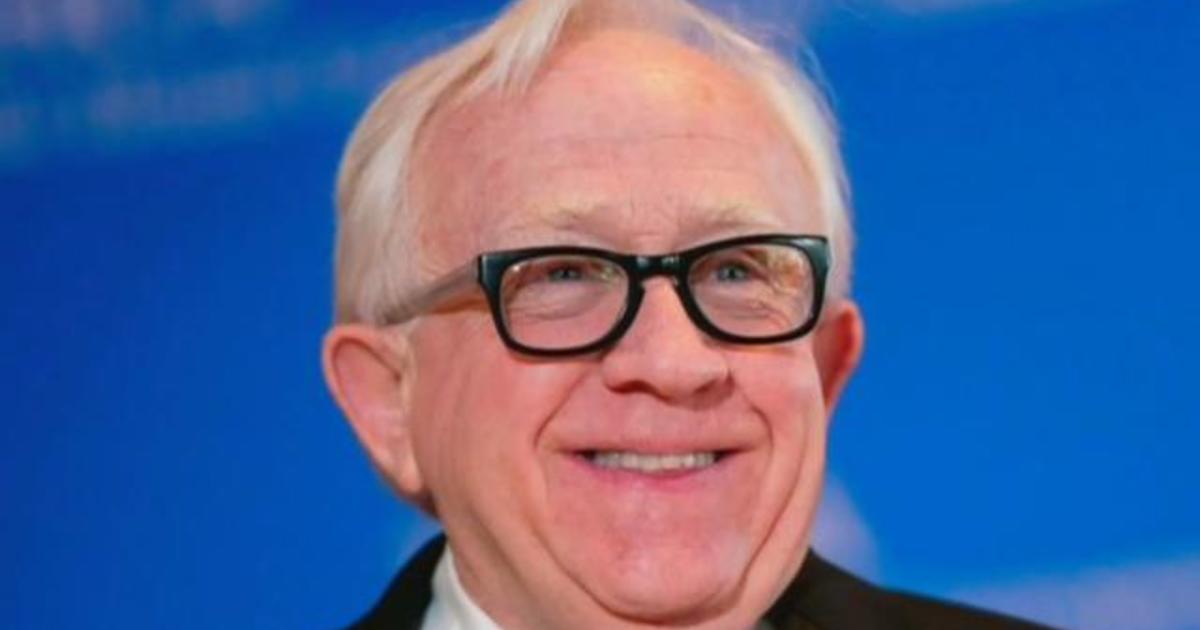

Murray is a civil rights advocate who speaks and writes about racial discrimination in the criminal legal system. Murphy is an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, who successfully represented Murray on appeal.

Dexter Murray, Adam Murphy

Source link

:quality(70):focal(1541x1256:1551x1266)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/SAEOE5YRTZBSBEBXWPVT7T5RWA.jpg)