Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

[ad_1]

It’s a sad fact that identities of people who were enslaved in the United States have historically been obscured, if not completely unreported. But a Boston-based non-profit organization hopes to bridge the gap between living descendants of Africans today and their often forgotten ancestors.

The long-term goal of American Ancestors’ 10 Million Names project is to recover every name of the estimated 10 million men, women, and children enslaved on the land that became the United States.

American Ancestors is the global brand of the New England Historic Genealogical Society. NEHGS was the first genealogical society in the nation, established in 1845. Their newest initiative, 10 Million Names, combines the work of historians and genealogists to bring the past to the present.

American Ancestors has shifted to a broader perspective in recent years, moving well beyond New England. Recently, for instance, they worked with Richard Cellini — now a member of the 10 Million Names advisory board — on the Georgetown Memory Project.

Through their collaboration, the memory project presented the family history of 272 people found on a bill of sale between Jesuit priests of Georgetown University (then Georgetown College) to plantations in Maryland and Louisiana.

Lindsay Fulton is chief research officer for American Ancestors. She has been involved with 10 Million Names since its inception, and is a nationally recognized genealogist and lecturer.

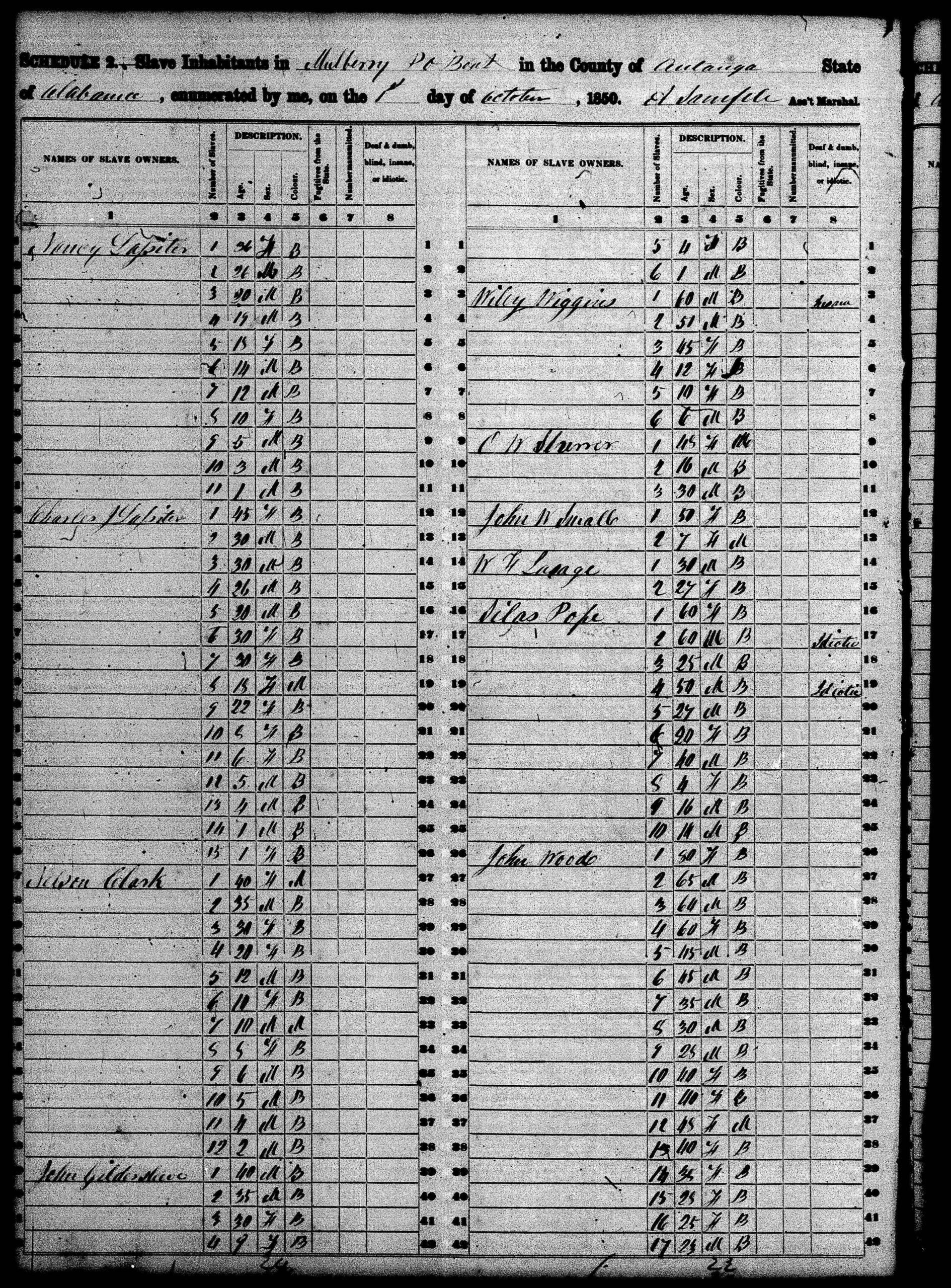

According to Fulton, this work in particular is difficult because there are not well-kept records of formerly enslaved people. In what she refers to as the “1870 brick wall,” it was not until that year that all people (including the formerly enslaved) were well-noted in the U.S. census.

“We found that it’s more effective to move from records that we have in the past, so in that period of enslavement, and then bringing them forward. It’s easier for me to find someone in 1860, and then try to look for them in 1870,” post-emancipation, Fulton said.

To accomplish this, American Ancestry is working in conjunction with historians. One of them is Dr. Kerri Greenidge, an associate professor of history at Tufts and a member of the Scholar’s Council for the 10 Million Names project.

In a statement to Boston.com, Greenidge wrote, “Often, when African Americans conduct their history, it is difficult to trace as far back in time as many European Americans.”

Currently, Fulton is looking at documents of slave narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project. These are oral histories collected across the U.S. from formerly enslaved people by federally employed writers. In these interviews, people often name their family and the places they grew up, allowing genealogists like Fulton to make vital connections.

“We are by no means the first organization to start researching enslaved individuals,” Fulton acknowledged. “There’s millions of Americans who have searched and researched their own family trees. So we want to be kind of the hub for people to come to share what they’ve been able to discover.”

In Massachusetts, historians and genealogists are currently focusing on Cambridge and New Bedford. Both towns were once a part of the Maritime Underground Railroad, used by famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Documents like crew lists may reveal names.

“The wonderful part about this project, in my opinion, is that it’s bringing all of the players to the table,” Fulton said.

Between the genealogists, historians, partners, and citizens who send in their family histories, 10 Million Names is a massive collaboration.

Another key partner is chief historian of 10 Million Names, Dr. Kendra Taira Field. Field is an associate professor of history and the director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at Tufts University.

In a statement to Boston.com, Field wrote, “This project has brought historians and genealogists together, so that we can connect details of the genealogical work to broader historical patterns. This is the largest scale collaboration between professional historians and genealogists that I’ve seen.”

While this body of work will take years to finish, information will be centralized at 10 Million Names for free. Their goal is for all of these records to be available to the public, so people can begin making those connections with their ancestors. Those whose families were severed by the violence of American slavery can take the steps to find their roots.

According to Fulton, “This will be my greatest contribution to humanity.”

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

[ad_2]

Adora Brown

Source link