[ad_1]

Asimina triloba

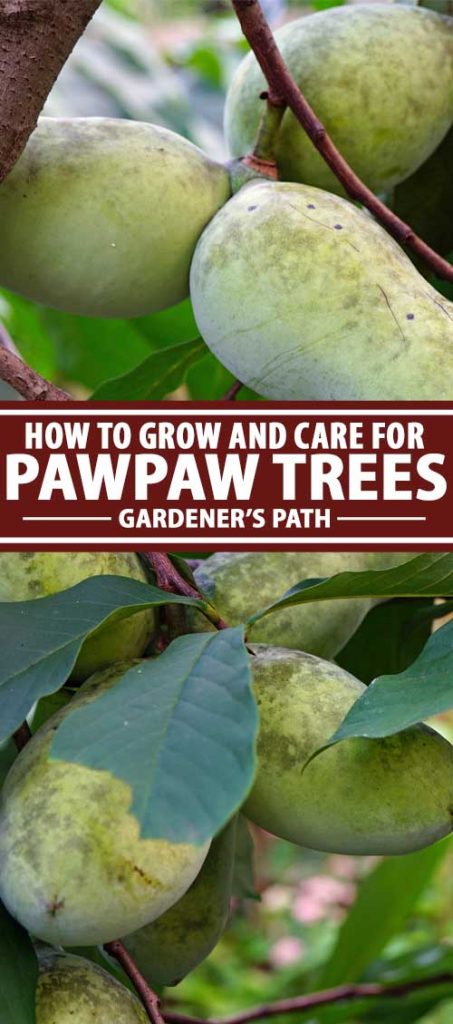

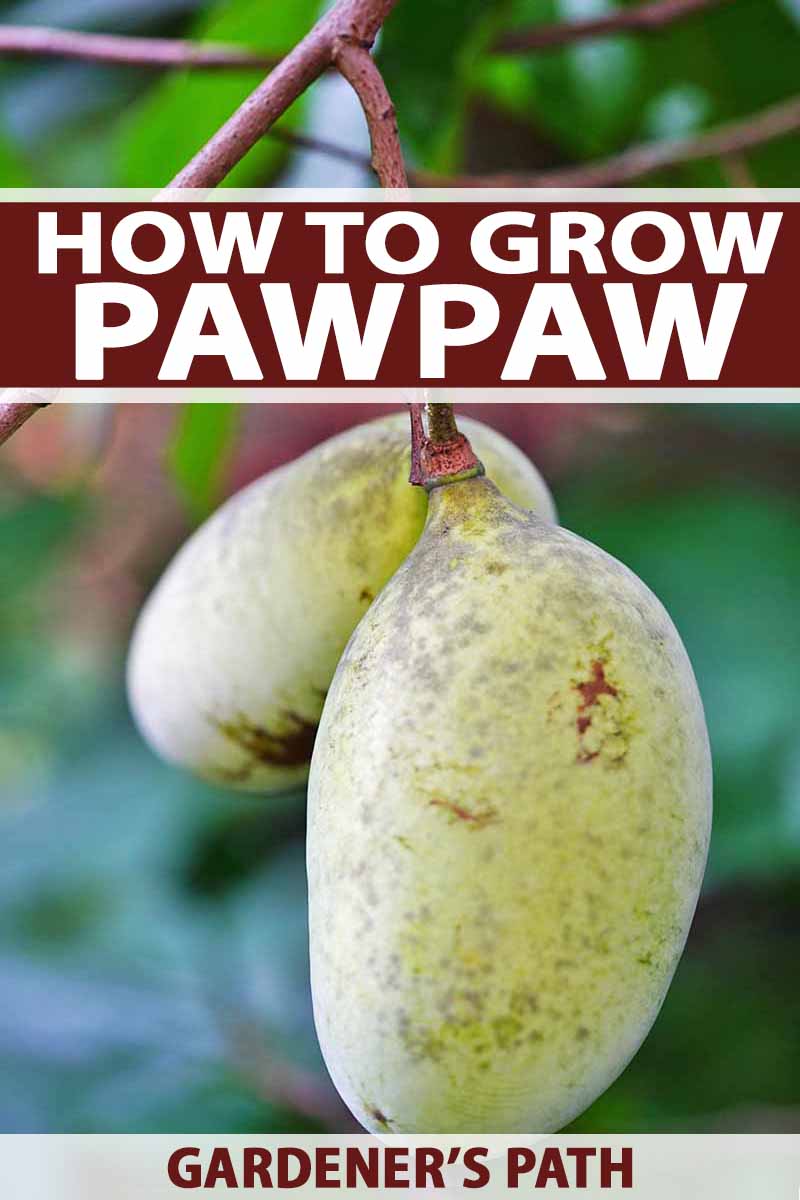

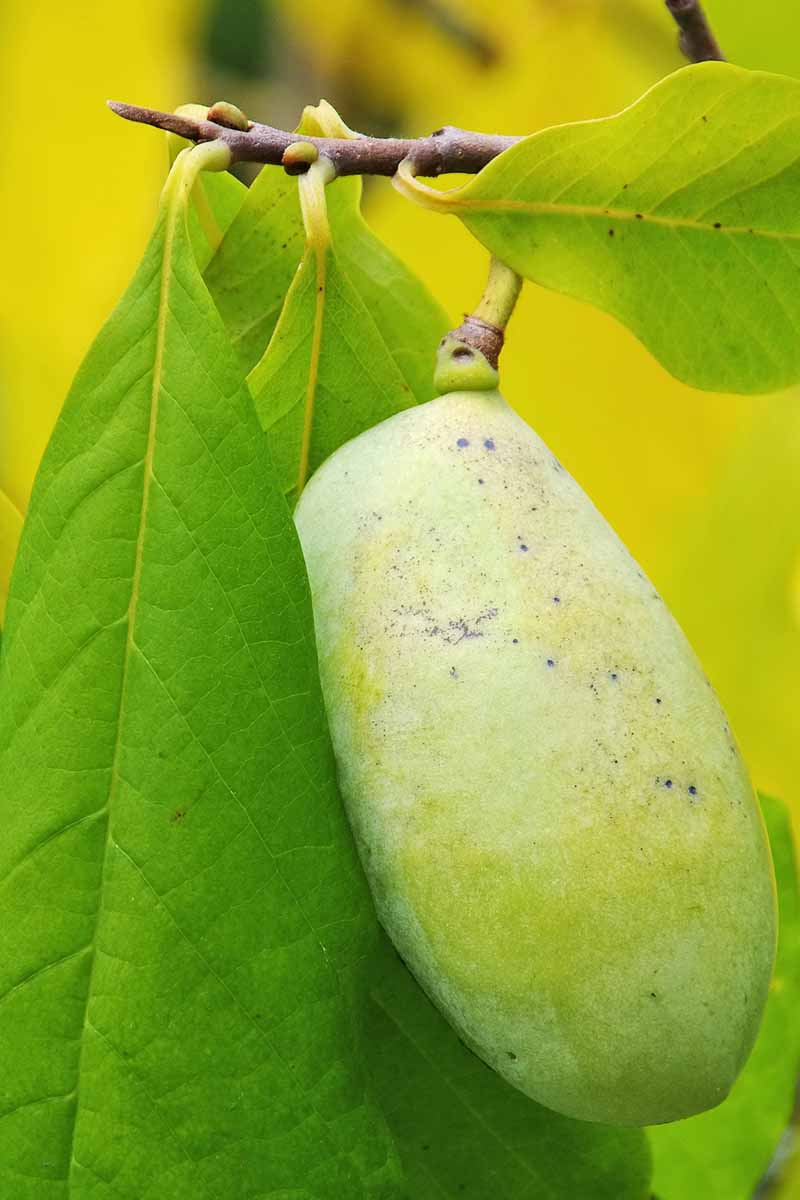

Have you heard of the pawpaw, Asimina triloba? It’s the largest native North American fruit, and it has a tropical flavor and custardy texture.

If you’re confused, that’s because there are other tropical fruits called pawpaw, including the papaya, Carica papaya, and the graviola, or soursop, Annona muricata.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Unlike them, A. triloba grows in the temperate regions of USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 9, and has three intriguing qualities:

- It is a hardy deciduous perennial that grows as either a tree or shrub.

- Fruit is optional because the plant does not self-pollinate.

- With or without fruit, its drooping golden leaves in fall and musky, maroon flowers in spring make for a striking and structural focal point.

Read on to discover a temperate zone fruit once so popular it was celebrated with song, and learn how to grow it in your home landscape.

Here’s what’s in store:

Consume with Caution

Also known as “Indiana banana,” “Quaker delight,” “Appalachian banana,” and “poor man’s banana,” the pawpaw is a member of the Annonaceae, or custard apple family that includes cherimoya, Annona cherimola, and graviola, aka soursop, A. muricata (mentioned above).

And while the fruit has an appealing flavor, there are some people for whom consumption causes stomach upset. This is due to the chemical compound annonacin, which is also present in the bark and seeds.

The NC State Extension categorizes the level of toxicity from eating pawpaw as low, with the summary: “Fruit edible but some people suffer severe stomach and intestinal pain; skin irritation from handling fruit.”

In addition, the pulp and twigs contain acetogenins, metabolic compounds toxic to some cancer cells. However, Sloan Kettering advises its cancer patients: “There are no published clinical studies in humans to determine the safety of pawpaw for cancer treatment,” and goes on to warn patients who wish to consume the fruit that they may experience allergic reactions, neurotoxic effects, or vomiting if they do.

Pawpaw fruit perishes quickly after ripening, so it is not currently a commonplace grocery store commodity. Instead, it’s the domain of small-scale farmers and home growers who often supply it to farmers markets.

In addition to fresh fruit and frozen pulp, extracts are available in pill form for the purported purpose of boosting cell health.

Professor Bruce Bordelon, of the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Purdue University, concurs with the warnings and says, “When it comes to pawpaw, perhaps it is best to enjoy the fruit in moderation.”

“Way Down Yonder”

At a length of up to six inches, the pawpaw is North America’s largest native fruit.

It’s an overlooked legacy from Mother Nature that harks back to gentler times, when bonneted girls and straw-hatted boys went fruit picking in bare feet on summer mornings.

Where, oh where is pretty little Susie?

Way down yonder in the pawpaw patch.

These old Appalachian lyrics have been sung around many a campfire, including the Girl Scout jamborees of my childhood. But although I was in prime pawpaw territory, I grew up with only the word, and not the sweet flavor, on my tongue.

So, what’s a pawpaw patch?

A. triloba is a plant that thrives in organically-rich areas along waterways, in woodlands, and on hillsides, where the ground is especially moist. It may have the habit of either a tree or a shrub.

As an understory plant, beneath the partial shade of deciduous trees, it is shrub-like. But in the full sunshine of open spaces, it’s a pyramid-shaped tree that may exceed 30 feet in height.

Both types generate suckers that grow into additional plants and eventually form a thicket of growth, or the proverbial patch.

Pawpaw Pioneers

My first physical encounter with this plant, no lie, was in my sister Susie’s backyard. Yes, after singing about them for years, she grew up and planted a patch of her own.

And in my area, the fruit is gaining popularity thanks to an organization called the Philadelphia Orchard Project that plants trees for public foraging and supplying local farmers markets.

This is no easy task, as fresh-picked fruit lasts only about two days.

Athens, Ohio grower Chris Chmiel runs Integration Acres, the “world’s largest pawpaw processing plant.”

I recently heard Chris speak as a guest on the Gastropod podcast, in an episode entitled “Pick a Pawpaw: America’s Forgotten Fruit.” Because the fruit is so perishable, his team picks, processes, and sells it frozen. Buyers include craft brewers.

Chris has revived interest in this under-cultivated fruit by founding the “largest pawpaw festival in the world” and sharing its folk culture.

It seems that the location of patches in the wild and the names of places in the “pawpaw belt” support the theory that Native Americans not only foraged for the fruit, but likely cultivated it as well.

From Early American days to the beginning of the twentieth century, folks scooped the sweet flesh from ripe skins to make jams and puddings, finding it plentiful in the wild. Herbal practitioners used the toxic seeds, bark, and leaves in a range of homeopathic remedies, from insecticides to emetics.

In 1916, The Journal of Heredity’s Contest for the Best Pawpaws invited participants to send their local varieties to the American Genetic Association. Prizes were awarded for the best, and they were studied for possible propagation.

Over the years, the early pioneers of propagation died, commercial viability did not come to fruition, and research waned. Sadly, at least 35 cultivars identified between the 1890s and 1960s are now extinct.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that serious interest resurfaced. When West Virginia University plant genetics student Neal Peterson tasted the fruit, he was inspired to pick up where early researchers had left off.

In 1999, he partnered with Kentucky State University to conduct the Regional Variety Trial, with the cooperation of numerous universities, to evaluate cultivars for possible commercial production.

Today, Peterson continues his work, cultivating, researching, and teaching in the Kentucky State University Pawpaw Program, and Peterson’s Pawpaws are widely available for the home gardener. Large-scale commercial production remains a goal of the future.

A Patch of Your Own

Are you ready to revive a once-celebrated native fruit in your outdoor landscape?

Here’s everything you need to know to ensure success.

Soil Requirements

For optimal results, you’ll need moist soil with a neutral to slightly acidic pH that is organically rich and drains well.

Contact your local extension office to have your soil tested, and adjust pH and add amendments like compost and nutrient-rich fertilizer per the instructions in your test report.

Location Selection

To grow a tree, choose a location in full sun. It should be somewhat sheltered, either by a nearby building, fence, or shrubbery, because high wind is known to damage pawpaw, permanently twisting its branches.

Mature dimensions may reach 30 feet tall and 20 feet wide, with compact branches for a conical shape.

For cultivation as a shrub, select a partially shaded location beneath a canopy of tall deciduous trees, where looser, sprawling growth has room to roam.

Pollination and Fruit

Decide whether you are interested in fruit, because pawpaw pollination poses a challenge.

The best method to ensure a fruit crop is to plant at least two totally different cultivars on your property (and three is even better), as well as an array of nectar-rich plants that attract pollinators. The pros at Peterson Pawpaws recommend planting trees no more than 30 feet apart.

The horticulturists at the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center in Texas explain that pawpaw produces many flowers that seldom self-pollinate, and are in fact, “self-incompatible.” Flies and beetles are the major pollinators of A. triloba, and growers have been known to hang roadkill from branches to attract as many flies as possible.

Another method of pollinating is to use a paintbrush and manually pollinate pawpaw blossoms of one variety with those of another, a technique that’s beyond the scope of this article.

Rodale’s Ultimate Encyclopedia of Organic Gardening says there’s an old cultivar called ‘Sunflower’ that doesn’t require cross-pollination, if you can find one!

Quality Plants for Best Results

After your site is selected and the soil prepared, it might be tempting to find a wild pawpaw patch and dig up a seedling to take home. This is not a good idea, for two reasons:

First, the plant has a long taproot that may be damaged.

Second, plants dug in the wild seldom transplant well to the home garden.

Per Carla Emery, author of The Encyclopedia of Country Living, if you find some ripe fruit, simply put it in the ground whole and cover it with a thin layer of soil. If seeds sprout, thin them out later.

Like many seeds, those of A. triloba require a period of cold stratification to germinate. But unlike many seeds, they must be kept moist. So, planting whole fruits post-harvest in the fall addresses both issues.

However, even if they do grow, plants and fruit produced from wild seeds are likely to be inferior to today’s cultivars. These cultivated varieties are bred for desirable characteristics like disease resistance and exceptional fruit quality.

Also note that the seeds from modern varieties, particularly hybrids, produce uncertain results, and often bear no resemblance to a parent plant.

Another propagation method is to take a stem cutting (scion) from a tree or shrub, and graft it onto sturdy rootstock (clone).

Planting Directions

Spring and fall are the ideal times to put plants in the ground, when the trees are dormant. Here’s how:

- Trees should be planted 15 to 25 feet apart to ensure adequate space for growth, but close enough for pollination.

- Work the soil down about a foot until it’s loose and crumbly. You’ll want to make it deep enough (about as deep as the pot) so that the brittle tap root is not stressed, and wide enough that the entire root system is not compressed. You can amend with coconut coir fibers or peat moss if the soil is compacted.

- Unpot your plant and loosen the soil and any tangled roots.

- Place the plant with its dirt into the hole, making the top of the pot soil even with the ground soil.

- Tamp the soil down.

- Make a ridge of earth around the plant, and apply a layer of mulch to aid in moisture retention.

- Water thoroughly and keep the soil moist throughout the growing season.

Pests and Disease

Pawpaw is not prone to pests or disease, especially when you start with a plant that has been expertly bred.

Fungal or bacterial leafspot sometimes occurs on leaves that are too wet for too long, and may be treated with a copper-based fungicide. Be sure to choose one that is safe for use on edible fruit.

The pawpaw peduncle borer (Talponia plummeriana) is one of the few pests that specifically targets this species. The larvae consume portions of the flowers when the trees are blooming, which leads to a smaller crop.

Spider mites, hornworms, various caterpillars, and Japanese beetles can all attack the leaves.

Care and Maintenance

If you start from seed, it may take a couple of months before you see a sprout, because the long tap root grows first.

Water deeply once a week during the growing season, and more if rainfall is scant. You may apply a diluted all-purpose fertilizer to seedlings per package instructions.

The experts at University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food, and Environment say that first-year seedlings are very sensitive to ultraviolet light and require shading from intense sun, as well as mulch and consistent watering during dry spells.

They also recommend that suckers, the new shoots beside the main trunk, be hand pulled, as opposed to being pruned or mowed, because the latter methods encourage more to grow. Of course, if you want a patch, leave them alone.

Similarly, fruit that falls and decays contains seeds that may sprout. Remove unwanted seedlings by hand pulling.

In spring, apply a layer of mulch to aid in keeping the soil moist. Pruning is not required, except to remove dead or damaged branches. However, as fruit sets on new growth, some people prune in an attempt to increase yields.

You may fertilize mature trees and shrubs each spring with an all-purpose, slow-release granular fertilizer. Sprinkle it in a circle a few inches out from the base of plants. As weeds begin to grow in summer, clear them away to inhibit pests and disease.

Be patient when expecting fruit. It may take up to eight years before it appears, although some of the newest cultivars fruit much sooner. Take care to maintain even moisture while fruit sets, as a drought may cause it to suddenly drop off.

Where to Buy

You can find pawpaw plants available in garden centers and online.

Fast Growing Trees carries one- to two- and three- to four-feet American pawpaw trees.

Remember that you will need two different varieties to produce a fruit harvest.

Harvesting

Fall is harvest time in the pawpaw patch. There is variation among the different cultivars, but September is generally peak pickin’ time.

This is when green fruits begin to soften, generally turning yellow and then brown.

It’s hard to know when to pick, and many folks use the time-honored technique of shaking the tree or shrub and taking home whatever falls off. Don’t pick too soon, because a pawpaw ripens best on the tree, and may not ripen further after harvesting.

You have about two days to consume your crop before it starts to rot, so don’t waste any time! Simply slice the fruit lengthwise, remove the seeds, and spoon up the sweet, creamy, yellow pulp for a truly tropical sensation.

Freeze any pulp you can’t consume fast enough. You can use it in everything from breads and cakes to mixed drinks, ice cream, and smoothies. I don’t recommend refrigeration because fruits picked ripe are on the verge of rotting, and emit a strong, albeit fragrant odor.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Small, deciduous pyramidal fruit tree | Attracts: | Deer and other wildlife during fruiting |

| Native to: | Temperate North America | Tolerance: | Partial shade |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5-9 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Season: | Fruits ripen from mid-august through October depending on cultivar and location | Soil Type: | Fertile and loamy |

| Exposure: | Full sun in northern growing zones, partially shaded in southern regions | Soil pH: | 5.5-7 (Slightly acidic) |

| Time to Maturity: | 5-8 years from seed, 3-4 years from potted transplants or grafted cuttings | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 15 – 25 feet | Companion Planting: | Other understory plants and shrubs such as blackberry for fruit production or flowering dogwood for aesthetics |

| Planting Depth: | Same as nursery pot, or set crown of bare root stock just below the soil surface – be aware of brittle tap root | Family: | Annonaceae |

| Height: | 25 feet at maturity | Genus: | Asimina |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | triloba |

| Common Pests: | Pawpaw peduncle borer, papaya fruit fly, fruit eating wildlife | Common Disease: | Powdery mildew, black spot |

See you in the pawpaw patch!

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy others on topics such as growing fruit trees, ornamental trees, and landscape shrubs.

And if you’re a native plant aficionado, you won’t want to miss our collection of true-blue wildflowers.

[ad_2]

Nan Schiller

Source link