[ad_1]

Physalis philadelphica

A tart gift from Mexico, tomatillos (Physalis philadelphica) are commonly used by chefs and home cooks throughout the United States and worldwide to add a piquant va-va-voom to sauces and chutneys.

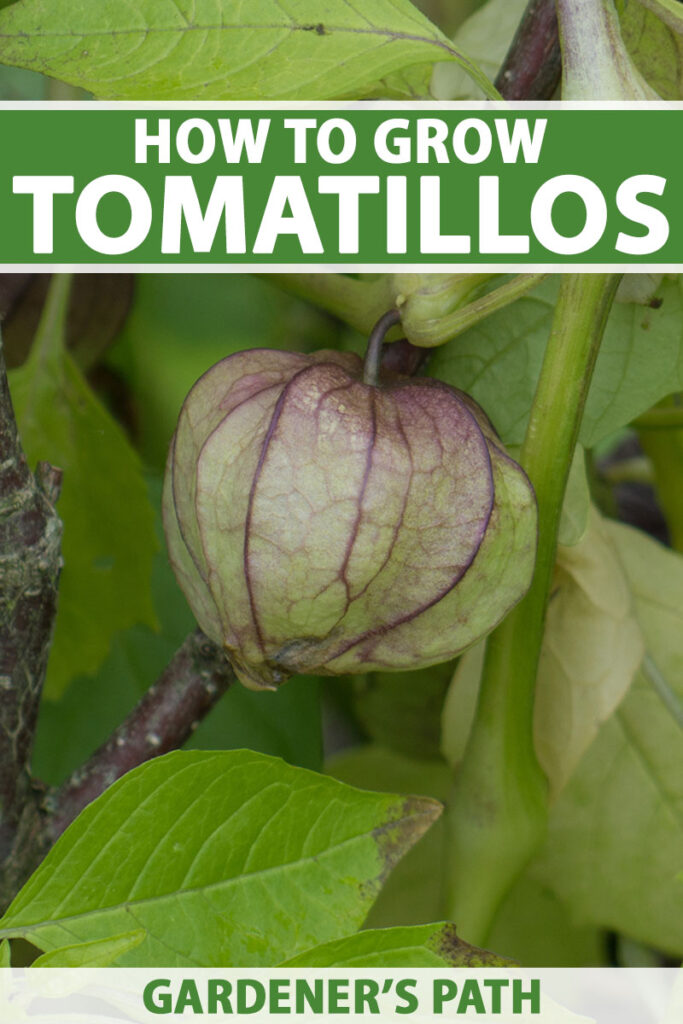

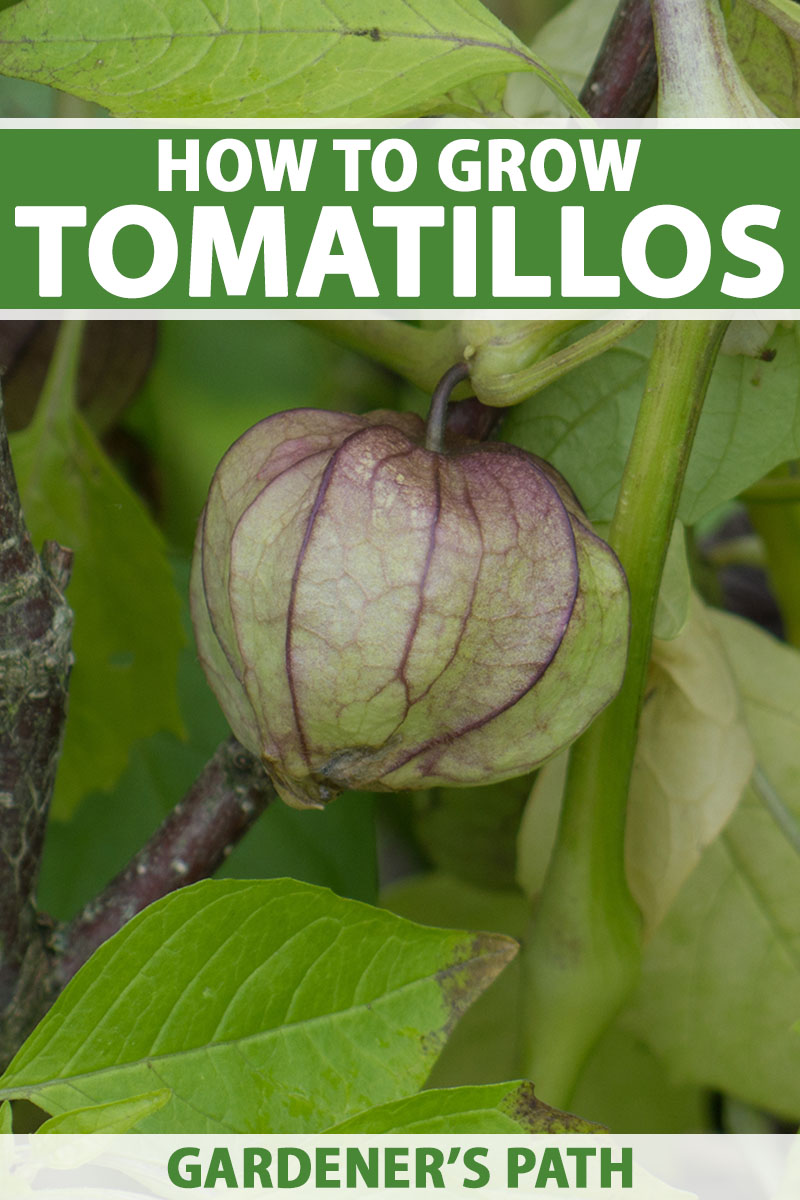

Beneath an intriguing yet inedible, papery husk lies a fruit that, while mimicking the appearance of a green tomato, tastes nothing like a tomato.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

A tomatillo’s flavor instead is often described as citrusy, tart, sour, and tangy. Some compare the fruit’s taste to a ‘Granny Smith’ apple or a green grape.

If you’ve sampled a salsa or jam containing these green wonders – or even a tomatillo mojito – you may have considered adding tomatillo (pronounced toh-mah-tee-yo) plants to your garden.

Let’s explore the taxonomy and history of the plant, and then we’ll look at how to grow and harvest it. Here’s the lineup:

What Are Tomatillos?

Tomatillos are part of the nightshade (Solanaceae) family, along with tomatoes and peppers. The leaves look a bit like those of eggplant, another nightshade plant.

Nightshade plants are easy to identify visually as relatives because they each produce the same particular type of flower.

The fruit’s very name is a misnomer. “Tomatillo” means “little tomato” in Spanish, and while they are distantly related, the tomatillo is definitely not a tomato.

Nevertheless, nicknames linking the two tasty fruits abound, with the tomatillo also being referred to as “tomate verde,” or green tomato, and “husk tomato.”

And with a few exceptions, home gardeners can use the same strategies and techniques to grow tomatoes and tomatillos.

Before you start, it’s helpful to know a bit of background about this core ingredient in Mexican cuisine, particularly the ever-popular salsa verde.

Cultivation and History

Originating in Mexico and Central America, this citrusy fruit has been an important food crop for millennia, though the plant has been around for even longer.

In early 2017, Peter Wilf at Pennsylvania State University in University Park and colleagues at the School of Integrative Plant Science at Cornell University and the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research at Egidio Feruglio Paleontological Museum in Argentina reported their discovery and analysis of a 52-million-year-old fossilized tomatillo found in the Patagonia region of Argentina in the journal “Science.”

Tomatillo plants and related members of the Physalis genus grow wild throughout their native regions.

Some referred to as “wild tomatillos” or “longleaf ground cherries” grow wild in parts of the midwestern United States where they are derisively called weeds and are considered invasive, despite their edibility.

Historical records show that numerous North American native tribes used the wild fruits (Physalis longifolia) to treat headaches and stomachaches, according to a publication of the Native Medicinal Research Program at the University of Kansas.

Prized for their unusual flavor and bright green or purple color, the tangy fruit of P. philadelphica are now cultivated and enjoyed worldwide. They can be eaten raw but most commonly are cooked.

Interested in adding this unusual vegetable to your garden rotation? Keep reading for tips, from sowing to serving.

Propagation

In North America, these plants are grown as annuals.

As their popularity spreads, seedlings are becoming more commonly available at local garden centers, though not always at big box stores. You can also find mail-order seeds and propagate your own.

If you go the seed route, start them indoors six to eight weeks before the last frost is expected in your area.

An important consideration when selecting transplants or starting seeds: Because tomatillos are not self-pollinating, they must be planted in groups of at least two to ensure fruit.

Most gardeners find two to four plants produce sufficient fruits for plenty of salsa verde.

As for transplanting, whether you’ve purchased starts or grown your own, you’ll want to harden them off the week before you put them in the ground.

Start by setting them outside for an hour the first day, then add an hour or two on successive days until the plants are accustomed to the increased light and differences in temperature outdoors.

Like tomatoes, you’ll encourage strong, healthy plants if you bury two-thirds of each transplant to enable additional root growth from the stem. Backfill with loose, fertile soil and water the plants well at the soil line.

From there, the plants will need just a bit of care to grow to a healthy size, flower, and then start producing that coveted bumper crop of tart, green fruits for cooking and preserving.

How to Grow

Site selection is important when growing P. philadelphia.

Though the tomatillo is a lighter feeder than the tomato, it does need garden space with fertile loam amended with plenty of composted manure or other organic material to improve aeration and drainage.

Work about two inches of compost into the soil at least a couple of weeks ahead of planting, or a season ahead if possible.

Aim for soil in the pH range of 6.0 to 6.8, which you can determine using a soil test.

Consider growing your plants in raised beds if you have heavy clay soil – or at least until you can amend the soil for a season or two first.

The tips in our guide to growing tomatoes in clay soil will also apply to tomatillos.

The plant’s bright yellow flowers will attract bees and other pollinators, so it’s a good idea to grow them at least a few yards away from any areas of your yard that have been treated with insecticides.

You might also add nasturtiums or marigolds as companion plants that will attract pollinators.

Like their cousin the tomato, they want lots of sun, so pick an appropriately bright location.

Space plants about three feet apart. These semi-determinate plants tend to sprawl, growing three to four feet tall and wide, so you might want to use a trellis, stake, or cage to support the plants and keep the fruits off the ground.

Tomatillos prefer well-drained soil, and they can tolerate moderate drought conditions. They do best, however, with an inch or so of water per week. And they certainly won’t grow well in soaking-wet ground.

Consider drip irrigation for these thirsty plants. If you don’t want to go to the trouble, be sure to water at the soil line, not from above the plant, to prevent disease and promote healthy growth.

Once the plants are at least a few inches tall, add a two- to three-inch layer of organic mulch around them to conserve soil moisture and suppress weeds.

If you start with amply fertile soil, the plants should be able to make it through the season without additional fertilizing. In fact, overfertilizing can lead to poor fruit set and the development of leaves over fruits.

When growing in lower-fertility soil, consider side-dressing plants with a tablespoon of 20-0-0 NPK fertilizer when they’re about four weeks old and again at eight weeks old.

Tomatillos are well-suited for container growing. Use a five-gallon pot for each plant.

Keep an eye on soil moisture, as containers dry out more quickly. And follow our guide for growing tomatoes in containers for more tips that also work for P. philadelphia.

Growing Tips

- Start seeds indoors four to six weeks before the last average frost in your area.

- Transplant or sow in fertile, well-draining soil.

- Consider supporting plants with tomato cages to keep fruits off the ground and reduce sprawling.

- Supplement with one inch of water per week if it hasn’t rained enough to supply that amount.

- Add a layer of straw mulch or grass clippings when plants are a few inches tall.

Cultivars to Select

‘Toma Verde’ is among the more common cultivars, producing the classic, golf-ball-sized green fruit.

Seeds are available in various packet sizes from High Mowing Organic Seeds.

‘Grande Rio Verde’ is another well-liked variety, producing a larger, two- to three-inch sweet spheres.

Seeds are available from Eden Brothers.

A number of purple types also exist, including ‘Purple Coban,’ ‘Tiny from Coban,’ and ‘De Milpa.’

Organic purple tomatillos of an unspecified cultivar are available in 80-seed packets from Botanical Interests.

Managing Pests and Disease

It’s a good idea to plant onions nearby, to help with pest control.

No particular pest is unique to the tomatillo, but their leaves are susceptible to the usual suspects, such as cucumber beetles, potato beetles, and other leaf-loving bugs.

Pick them off or use a natural insecticide to keep them away.

You may also see aphids, which can be squirted off with the hose.

If they persist, consider treating them with neem oil. You can find a quart or gallon of ready-to-spray neem oil or pints of concentrate available from Bonide via Arbico Organics.

This 32-ounce spray bottle is ready to use,

Tomatillos are fairly disease resistant but may still fall prey to root rot when subjected to overly moist soil or standing water.

Also watch out for early blight, anthracnose, and tobacco mosaic virus.

Powdery mildew, which looks like a dusting of flour on the stems and leaves, can also damage the plants and slowly kill them. Learn how to prevent and cope with powdery mildew in our guide.

The best ways to prevent pests and diseases from taking hold is to destroy plant debris at the end of the harvest season, and rotate crops in your garden so you’re not planting tomatillos where they or other nightshades (particularly potatoes, as well as tomatoes, eggplant, and peppers) have grown in the previous two seasons.

This reduces pressure from harmful pathogens or insects that can survive in the soil or on plant debris from one season to the next.

Harvest and Storage

The fruit is ready to pluck 75 to 100 days after transplanting.

Pick tomatillos when they fill out the papery skins and their husks begin to split. You can gently pull a bit of one husk to the side to visually check the size of the fruit inside, or gently press the sides to determine if the fruit is starting to press against the sides.

When the fruit is still small and hard, and the husk is quite loose, it is too early to harvest.

Occasionally, the husk won’t split but turns brown and leathery instead. Tis is also a sign that the fruit is ready to be picked.

If the fruit turns pale yellow, you have waited too long. At this stage, the tasty interior becomes seedier, and the flavor loses its distinctive tanginess.

When you’ve identified a fruit ready for harvest, it’s best to cut it from the plant rather than pulling it, which might damage the stem. Compost damaged or overripe fruits.

You can store harvested fruits in their husks at room temperature for up to a week, or in the refrigerator, either loose or in a paper bag, for around three weeks. Avoid storing your harvest in plastic.

Peel away the husk before preparing for consumption. As you peel the green orbs, they will feel sticky. Just wash the fruit to remove the tacky residue.

Preserving

To freeze tomatillos, simply wash them, slice them if you like, and then freeze them in airtight containers. No blanching is required.

If you add plenty of sweetener, tomatillos are tasty in a sweet or savory jam. Our sister site, Foodal, provides jam-making basics.

You can also dehydrate the fruits. For basic instructions, refer to Foodal’s Ultimate Guide to Dehydrating.

Of course, I think the most appealing use of a bumper crop of these tangy garden-grown fruits is water bath canning a batch of salsa verde, or freezing it.

Foodal’s water-bath canning tips will assure your success.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Before you begin cooking with tomatillos, a reminder: They are in the same family as tomatoes, but the fruits are crisper and far more tart.

They tend to taste better with at least some cooking, much like eggplant, which are also related.

You can start with the traditional salsa verde. Foodal provides a basic recipe, and it’s addictive served on eggs, with raw veggies, or stirred into queso dip. Or just dip tortilla chips into the green, tangy goodness.

For a dip with a twist, try Foodal’s take on tomatillo guacamole.

Or use the tangy produce to make an entree like Foodal’s creamy chicken enchiladas verdes with charred tomatillo sauce.

With each plant producing pounds of tomatillos as the summer wears on, you may experiment with sauces in any number of traditional and innovative dishes.

Or, you may find yourself settling into a daily habit of chips and homemade salsa verde – and missing the ritual when the season ends.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial fruiting herbaceous plant, grown as an annual | Water Needs: | High |

| Native To: | Mexico and Central America | Tolerance: | Light shade, some drought |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-11 (annual); 10-11 (perennial) | Maintenance: | Low |

| Season: | Summer | Soil Type: | Organically rich |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 6.0-6.8 |

| Time to Maturity: | 70-100 days | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 3-4 feet | Companion Planting: | Basil, beans, carrots, chives, cosmos, garlic, marigolds, nasturtiums,, onions, parsnips, oregano |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), even with soil surface (transplants) | Avoid Planting With: | Broccoli, kale, radishes, and other brassicas; corn; other nightshades, especially potatoes |

| Height: | 30-40 inches | Family: | Solanaceae |

| Spread: | 36-48 inches | Genus: | Physalis |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Species: | Philadelphica |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, armyworms, cucumber beetles, cutworms, flea beetles, hornworms, potato beetles | Common Diseases: | Anthracnose, black mold, early blight, blossom end rot, Fusarium wilt, powdery mildew, root rot, tobacco mosaic virus |

The Tomato’s Tart Green Cousin

Growing tomatillos is a fantastic way to add a new and unusual edible to your kitchen garden. If you’re comfortable growing tomatoes, you should have no trouble growing their green cousins.

Are you intrigued? Ready to introduce a new plant to your spring garden?

Create a true salsa garden by installing some tomatillo plants next to your tomatoes and peppers – your family will thank you!

Add a comment below to tell us your tale of tomatillos.

And if this coverage is a good fit for your interests, you can learn more about growing other members of the nightshade family by reading these tomato, pepper, and eggplant guides next:

[ad_2]

Rose Kennedy

Source link