Journalism school is a good place for a pessimist.

There’s no shortage of people even in the country’s most venerated journalism programs who will happily tell you about the profession’s downslide. It’s economically unsustainable, far past the glory days of smoky newsrooms, gruff crime reporters on their third divorce and all the burnt coffee that sweet, sweet advertising money could buy.

And I’ll admit it, refreshing the homepage at 10 p.m. doesn’t punch the same way as a frantic editor yelling “Stop the presses!” when late-night news breaks.

Chris Roush’s new book, “The Future of Business Journalism, Why It Matters for Wall Street and Main Street,” tells a familiar tale: Business journalism used to be lucrative. Newspapers’ business sections had loads of readers with disposable income to spread around, and ad sellers were smart enough to tell that to the owners at the local appliance store, salon or whoever.

Newspapers began culling their business reporting staffs around the 2008 financial crisis, just as the country needed, more than ever, to understand what was going on in their local economies. Advertising dollars disappeared, especially as local businesses realized they could reach more people on new social media channels and online.

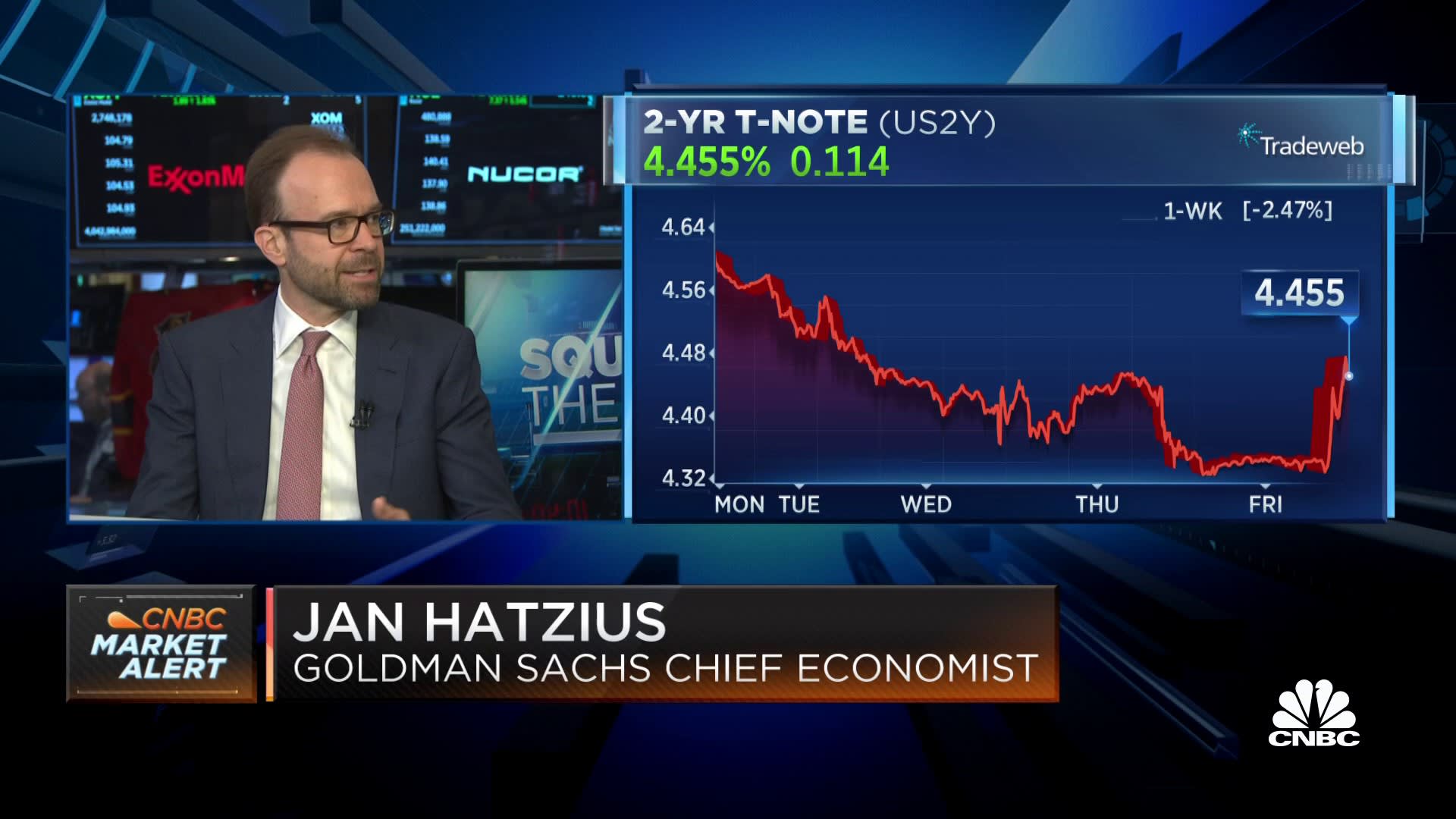

Then came Mike Bloomberg and his colorful keyboards. Turns out, people realize that good data and good journalism can make them a lot of money, and today places like Bloomberg and Reuters, which pair big data sets with scoop-heavy journalism in pricey subscription platforms, have the largest editorial staffs.

The problem with that? Business news is still available, and it’s valuable. It just goes to the people who can pay for it (and they pay a lot). It’s also mostly national news, leaving people in places like Des Moines, Iowa, and Atlanta struggling to understand what’s going on in their communities, or how big news events affect them.

So, that’s all still pretty grim. Where did that leave people like me, at 20 years old at the University of North Carolina, walking into Roush’s business reporting class for the first time? I took business reporting and economics reporting classes with Roush, now dean of the School of Communications at Quinnipiac University, when he ran the business journalism program at UNC.

Sure, reporting is fun, and it might be valuable, but it’s not worth much to me if I can’t make a career out of it. Screw it, maybe I should listen to my parents and go to law school. Or worse, into public relations.

But what sets Roush’s new book (and his classes) apart is his insistence that good journalism and profitable journalism are one and the same. I did not, thankfully, go to law school after taking Roush’s class. Instead I went to work at one of those local newspapers everyone liked to talk about.

They were one of the lucky ones that largely had a business desk still intact, but the empty chairs in the newsroom echoed the story that Roush told in his book. Still, local business leaders clamored for our coverage, and complained there wasn’t enough of it. That, Roush suggests, isn’t just a civic misstep, but a missed business opportunity.

Consider this publication. American Banker writes for banks across the country, and we’re one of the only publications providing dedicated community bank coverage. But how much of the story are the bankers in Omaha, Nebraska, missing if they’re only reading our banking stories but not seeing the trend pieces about meat processing plant layoffs right over the border in Council Bluffs, Iowa?

On a larger scale, most financial reporting now, in particular, focuses on Wall Street, Silicon Valley and Washington, and how the three intersect. Sure, these trends are important to understand, but so are the moves of state regulators, the contours of local economies and the personalities of figures about town. It can’t be the Wall Street Journals, the Bloombergs or even the American Bankers of the world that tell those stories. It has to be people embedded in those places.

Roush also brings up that financial journalism is mostly white, and largely still male, in a way that reminds us that the good ol’ days never quite existed the way we want them to. Business journalists might have caught on earlier to the trouble brewing in the housing market, he muses, if there had been more Black reporters in newsrooms at the time.

Reading my old professor’s words, I realized that critiquing the ways business and financial journalism goes wrong is easy, and the world certainly doesn’t need Chris Roush to do it. Where his book truly excels is his nuanced portrayal of the value of business journalism and, perhaps most important, how to fix its flaws.

It’s no secret that business journalism, particularly the kind that produces local coverage, has tricky economics. How do you make people pay for a product they expect to get for free? Maybe we should all Hail the Mouse and try to get bought by Disney, or jostle for a spot in the increasingly crowded newsletter market. Perhaps media startups like BuzzFeed are the key. Pick your celebrity crush and I’ll tell YOU which regulatory agency you are!

Startups like Axios, after all, have made a major local news push.

The big picture: Axios did see an opportunity in that local market I told you I worked in earlier, and have started a vertical and newsletter there.

• But Axios is betting a lot of its growth on a professional “Pro” service that will, once again, serve a high-paying business audience.

Roush has some practical suggestions for reporters: Make better friends with PR people, look at bankruptcy court filings and zoning documents to dig up good local stories, and start thinking of health care, in particular, as a story that affects every single aspect of the economy.

Local newsrooms could invest in artificial intelligence that takes some of the burden off overworked reporters, freeing them up to tell more compelling stories. Editors need to start building better pipelines of nonwhite reporters.

Perhaps most importantly, publishers and executives across the country should take a literal page out of Roush’s book, and start pitching business journalism as the competitive advantage it is.

Ultimately, though, none of this can happen unless there’s a demand. Local communities need to decide if the business of business journalism is something they value, and if it’s something they will support.

Claire Williams

Source link