Economists have long modeled environmental issues in the context of economic decisions and, in recent decades, have closely considered the implications and potential solutions to climate change. In 2018, William Nordhaus shared the Nobel Prize in economics for his work on “integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis.” Similarly, financial regulators and some central banks have begun to study how climate change risks could affect economic policy.

Economists often think about environmental issues quite differently from noneconomists, emphasizing the importance of the environment as one goal among many, while noneconomists often present environmental quality as an absolute imperative. For example, the United Nations Environment Programme publishes “Six Reasons Why a Healthy Environment Should Be a Human Right,” suggesting no space for trade-offs.

In this article, I explain how economists think about environmental issues, including climate change.

Trade-offs in a Simple Economy

Before delving into environmental issues, let’s briefly consider how economists think about the production and distribution of goods in a simple economy—one in which people like to consume wine and use machines. Because productive resources—labor and capital—are scarce, people must choose how to allocate these resources in producing wine versus machines. In making this choice, people are guided by their relative tastes for wine versus their desire for machines and the technology that determines the cost for both. Holding other things constant, the more that people like wine, relative to machines, the more wine will be produced—and the fewer machines. Similarly, the cost of producing the two goods determines their relative prices in the market.

In this simple economy, people trade off their relative preference for wine and machines with the relative cost of wine and machines to make themselves happy. There is no need for any outside intervention.

Pollution and Externalities

Pollution can create a role for government intervention, however. Suppose that producing machines causes pollution that makes people sick, whether or not they utilize machines. In this case, producing machines imposes an extra cost on society, called a negative externality, because it harms the public but is external to—not paid by—producers or consumers of machines. The cost of the machines that includes the harm done through pollution is called the social cost of the machines. Because the market price of a machine doesn’t reflect the social cost—which includes the cost of pollution—machines are too inexpensive. Society would be better off with fewer machines and more wine, but individual consumers have no incentive to buy fewer machines.

Pigouvian Taxes and the Environment

Society could benefit if the government taxed the pollution created during the production of machines or (less efficiently) taxed the consumption of machines. Such a tax, called a Pigouvian tax after the economist Arthur Pigou, would increase the cost of polluting, making it economically efficient to pollute less in production and consume less of the now more-costly machines. An attractive feature of Pigouvian taxes is that the revenue from those taxes can be used to pay for public goods or to reduce taxes on productive activities, such as income taxes.

Estimating the proper level for a Pigouvian tax can be difficult, however, because legislators or regulators would have to make decisions about trade-offs between a clean environment and other goods we want. Noneconomists often object to putting an economic value on human life or health, but individuals often trade off their own safety against expense and convenience. For example, very few of us buy the car with the very best accident protection, because it would be too expensive and might not have other features we desire. And even the safest car could be constructed to be even safer at greater cost.

A Pigouvian tax directly on pollution is generally the lowest-cost way to reduce the effects of pollution. Nonprice methods to reduce the consumption of machinery—such as outlawing machines altogether, or rationing the ownership of machines, or prohibiting the use of machines on weekends—are usually much costlier ways to reduce pollution. Sometimes nonprice regulations can be partially counterproductive in mitigating pollution. For example, U.S. fuel-economy standards increase the average fuel economy of U.S. automobiles, which causes people to drive more because driving is cheaper, but this driving partially offsets the gain from greater fuel economy. Making fuel more expensive would be a better idea because it would avoid this problem. This is called the rebound effect. Such regulations raise the price of large cars relative to small cars and thereby cause people to substitute from large cars to sport utility vehicles, which are not subject to the same standards.

Climate Change as an Externality

Greenhouse gases (GHGs) that cause climate change are also externalities, although they differ from traditional air and water pollution in at least three ways:

- GHGs produced anywhere affect the rest of the world through climate change.

- Most costs of GHG-induced climate change are not immediate but projected to come many decades in the future.

- GHG-induced climate change entails potentially irreversible catastrophic risks that depend on poorly understood feedback effects between temperatures and other natural features, such as ocean currents.

Although GHGs could be removed from the atmosphere through technical means or partially counteracted through geoengineering, such as spraying particles in the upper atmosphere to marginally reflect sunlight, the only currently practical solution to the risks of climate change is abating GHG emissions through taxes or quantity limitations. For example, removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is currently much more expensive than abatement, and geoengineering is poorly understood and carries risks that leave it as a last resort.

Pollution: Localized vs. Global Effects

Most pollution has mainly local effects, not affecting countries thousands of miles away. Therefore, lax pollution controls on the other side of the world are not of much concern. But GHG emissions anywhere can affect the whole globe through climate change. The United States and Europe are not the only or even the largest producers of GHGs, as seen in the following figure.

Share of GHG Emissions in Carbon Dioxide Equivalents by Country, 2019

SOURCE: Our World in Data.

NOTE: Top GHG emitters in the “rest of the world” category include Indonesia (4%), Russia (4%), Brazil (3%), Iran (2%) and Canada (2%).

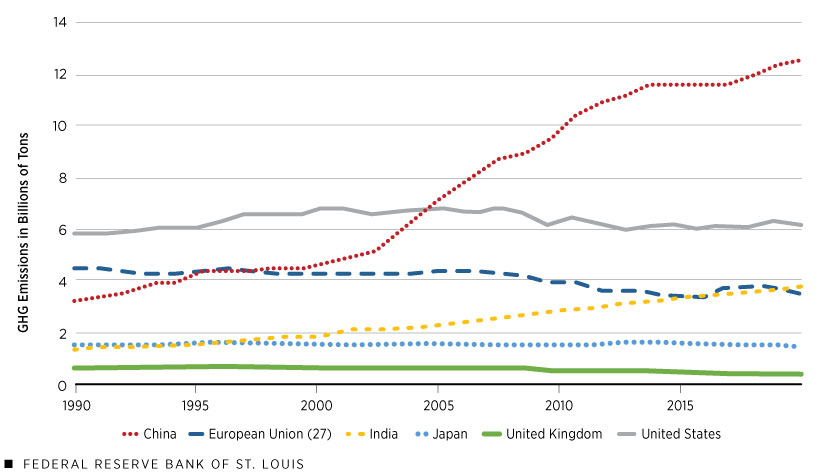

Further, while emissions in developed countries have been declining for about 20 years, those in the developing world have been rising fast (see, for example, data for India and China in the figure below). So, reducing GHG output solely in Western countries will only very modestly reduce global GHG emissions, which are what influence climate change.

Volume of GHG Emissions in Carbon Dioxide Equivalents by Country, 1990–2019

SOURCE: Our World in Data.

In other words, reducing GHG emissions involves a free-rider problem, in that nations can benefit from emissions reductions while not contributing to those reductions. Further, tight regulation or high taxes on GHG-intensive industries in one or several countries might actually be counterproductive if such rules push GHG-intensive industries to countries with very lax rules on emissions.

Although it will be very difficult to create incentives for all countries to jointly reduce their GHG emissions, it might be possible to do so through joint imposition of trade sanctions on noncooperative countries. The economist William Nordhaus calls this a “climate club.”

The Time Horizon of Expected Climate Effects

In considering appropriate policy, policymakers should compare the costs of reducing emissions now with the benefits in the distant future. Economists usually compare values over time—such as the price of a bond to the sum of its expected future payments—by discounting future values with an interest rate. When values in the future are uncertain, one must also account for the risks of the possible outcomes. When one compares values over long periods of time—50 or 100 years—the comparison becomes very sensitive to the discounting. For example, the present value of $1,000 to be obtained 100 years in the future is $369.71 if one discounts at a 1% rate, but the value is only $7.60 if one discounts at a 5% rate.

Economists have debated the appropriate way to discount future costs. A very low discount rate—one that values the future highly relative to the present—implies that society should immediately start large mitigating policies, while a higher discount rate implies much less costly mitigating policies that should gradually ramp up to avoid costly dislocations.

Catastrophic Risks

Finally, a peculiar feature of climate change is uncertainty about the effects; i.e., truly catastrophic effects are possible. For this reason, the economist Martin Weitzman argued that climate change mitigation should be considered insurance against a disastrous outcome, rather than simply a trade-off on the margins between current costs and a slightly warmer, less productive climate in the future.

An Economist’s Perspective on Environmental Policy

Economists see a role for government intervention to reduce the harm caused by pollution, but they usually see a clean environment as a good to be pursued along with other goods, such as food, shelter and clothing, rather than as an absolute value. Reducing GHG emissions to minimize climate change is unusually difficult because it involves other issues: reducing free-riding, determining an appropriate discount rate and insuring against catastrophic risks.

Notes

- There are also positive externalities that benefit people who are not involved in the transaction. For example, the creation of new technologies would produce positive externalities if people benefited from them without paying for their development.

- Taxing pollution, rather than machines, could be more efficient because it might allow machine producers to substitute less-polluting methods of manufacture.

- The substitution of carbon taxes for income taxes might be the basis of a compromise on domestic climate policy.

References

Arseneau, David M.; Drexler, Alejandro; and Osada, Mitsuhiro. “Central Bank Communication about Climate Change.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS), May 2022.

Greening, Lorna A.; Greene, David L.; and Difiglio, Carmen. “Energy Efficiency and Consumption—The Rebound Effect—A Survey.” Energy Policy, June 2000, Vol. 28, No. 6-7, pp. 389-401.

Nordhaus, William D. “A Review of the ‘Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change.’” Journal of Economic Literature, September 2007, Vol. 45, No. 3, pp. 686-702.

Nordhaus, William. “Climate Change: The Ultimate Challenge for Economics.” American Economic Review, June 2019, Vol. 109, No. 6, pp. 1991-2014.

Pigou, Arthur. The Economics of Welfare. Routledge, 2017. (First edition was in 1920.)

Stern, Nicholas. “The Economics of Climate Change.” American Economic Review, May 2008, Vol. 98, No. 2, pp. 1-37.

United Nations Environment Programme. “Six Reasons Why a Healthy Environment Should Be a Human Right.” April 13, 2021.

Weitzman, Martin L. “A Review of the ‘Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change.’” Journal of Economic Literature, September 2007, Vol. 45, No. 3, pp. 703-24.