The College of Saint Rose didn’t violate its own policies when it dismissed four tenured faculty members, according to a ruling Thursday by a New York appellate court. The unanimous decision overrules a lower court’s ruling last year that reinstated the four professors.

While the decision is specific to New York, one expert said, it does offer an example for other institutions trying to lay off tenured faculty members.

In the prior decision, a New York Supreme Court justice ruled that the private college in Albany had violated its own faculty manual by dismissing four longtime members of its music department. Saint Rose told the professors in December 2020 that they and about 30 other tenured faculty members would be laid off in 2021 as part of a cost-cutting plan that included eliminating 25 academic programs and $5.97 million in academic expenses. The college had retained less-senior faculty members, in what Justice Peter A. Lynch of the Albany County Supreme Court called a “select, narrow, and erroneous interpretation” of the faculty manual, seemingly “by design.”

It was a resounding, and rare, legal victory for tenured faculty members who get laid off. But it was also a short-lived one.

The state’s second-highest court found on Thursday, after a hearing last month, that Saint Rose had in fact not violated its faculty manual in terminating Yvonne Chavez Hansbrough, Robert S. Hansbrough, Bruce C. Roter, and the department chair, Sherwood W. Wise. The five-judge panel, whose decision was written by Justice Molly Reynolds Fitzgerald, noted that the manual stipulates only that the college should first consider “all reasonable alternatives before resorting to program reductions and any concomitant reductions in personnel.” Saint Rose had given the professors timely notice of their layoffs and allowed them to appeal through a faculty review committee, Fitzgerald said, writing that the decision “was supported by a rational basis, was not unreasonable, arbitrary and capricious or made in bad faith.” The court’s ruling also prevents the professors from suing the college for breach of contract.

The court’s decision to defer to Saint Rose’s interpretation of its faculty manual is consistent with precedent for the New York-specific legal proceeding under which the case was brought, said William A. Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions, at the City University of New York’s Hunter College. “It becomes not about the sanctity of the manual, but rather how to interpret it and whose interpretation is the one that the court’s trying to look for,” Herbert said. Guided by the terms of that legal framework, called an Article 78 proceeding, the court must only determine whether an institution’s interpretation of its faculty manual was “arbitrary and capricious,” which he described as a “relatively low standard.”

If, for example, a similar case arose whose retrenchment policy is codified by a collective-bargaining agreement, an arbitrator would not grant that same deference but would instead interpret the case independently, based on testimony.

It’s definitely a blow for the rights of tenured professors.

The specificity of Article 78 proceedings, which are “highly deferential to the institution,” make it difficult to draw broader generalizations about the ruling’s implications for tenure, said Matthew W. Finkin, a professor of labor and employment law at the University of Illinois College of Law and a labor arbitrator. The New York judiciary, Finkin said, is “disconnected from the weight of judicial authority on the law of tenure.”

While Thursday’s ruling shouldn’t have broader repercussions outside of New York, Finkin said, it does offer an example for other institutions trying to lay off tenured faculty members. The ruling also places a burden on future plaintiffs to educate the court that, although the New York decision would support the institution, the decision is not more broadly supportable, Finkin said. “There’s case after case that says you have to read rules of academic tenure in light of their history, of what they’re intended to accomplish and how they’ve been read and understood generally among institutions that adhere to the tenure system,” he said. “This court refuses to do that. It just looks at the plain text of the rule.”

In a statement to The Chronicle, Jennifer Gish, associate vice president for marketing and communications, said the college had “followed a process in the academic program reductions, and that process was affirmed by the courts. Those decisions were difficult, and the contributions of the faculty impacted will not be forgotten.” Gish added that the details of when the faculty members’ employment would officially end are still being worked out, and that “our focus is on the students and maintaining continuity of instruction and their academic success.”

The professors’ lawyer, Meredith Moriarty, said she was disappointed by the precedent the ruling set. “It’s definitely a blow for the rights of tenured professors,” Moriarty said. “I think it’s a blow for academic freedom, to be honest, because the opinion essentially states that courts have to give colleges complete deference in all their decisions in interpreting their own contracts.”

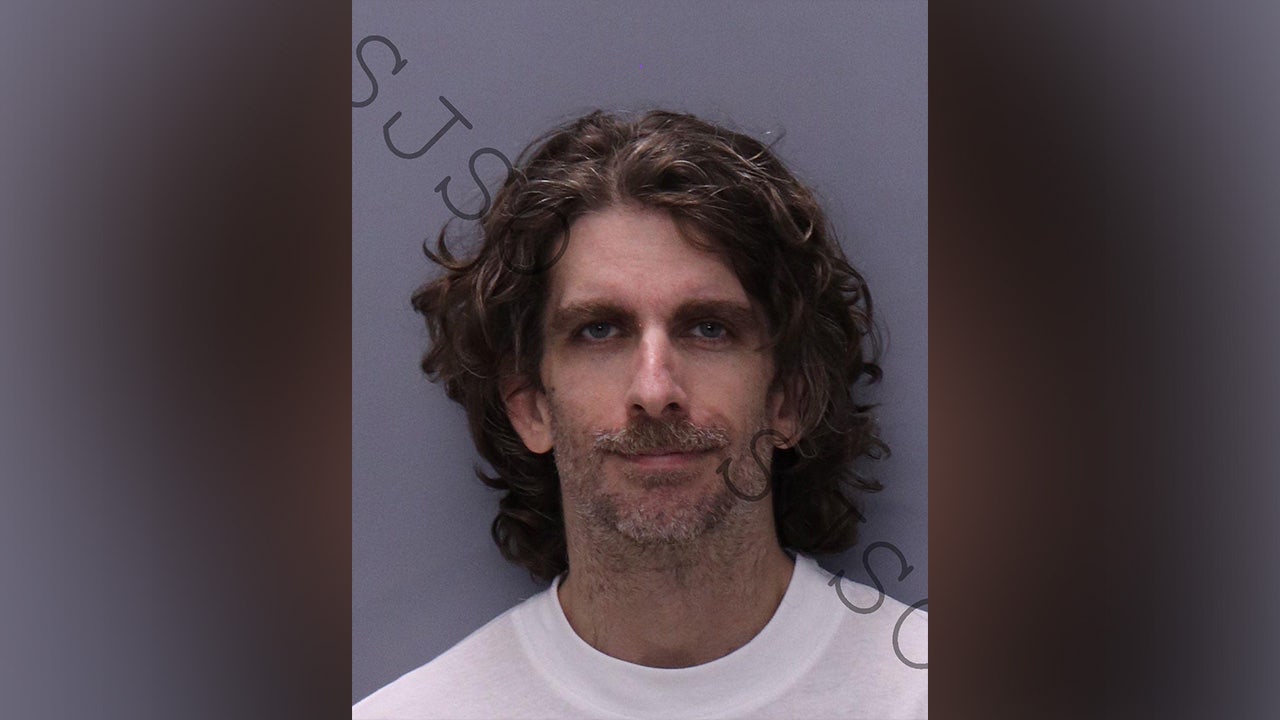

Roter, one of the professors, said in a statement to The Chronicle that he was “deeply disappointed” by Thursday’s ruling. “I believe this decision will have a chilling effect on higher education, especially regarding tenure and the enforceability of faculty manuals,” he wrote. “This decision puts one more nail in the coffin of tenure, a system which has enabled educators to speak and teach with academic freedom, unencumbered by the fear of termination.”

Roter and his colleagues can apply to appeal their case to the New York Court of Appeals, but they haven’t yet decided whether to do so, Moriarty said.

A Secret Counterproposal

Thursday’s ruling is likely to rankle faculty-rights and due-process advocates, including at the American Association of University Professors, which had already censured Saint Rose in 2016, a year after it cut 14 tenured appointments and 27 academic programs.

After the more recent cuts, Gregory F. Scholtz, director of the AAUP’s department of academic freedom, tenure, and governance, sent Saint Rose’s president, Marcia J. White, a letter of concern about the layoffs in the fall of 2021, saying the college had acted against the AAUP’s widely adopted Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure by not declaring financial exigency before laying off tenured faculty members. While Saint Rose’s faculty manual permits the college to terminate tenured faculty members because of “anticipated program reductions,” Scholtz wrote in the letter, “the AAUP does not regard the mere anticipation of program reductions as a legitimate basis” for laying off tenured faculty. (Scholtz was not available for comment on Thursday’s ruling.)

The process that led to the four music professors’ layoffs began when chairs in the college were asked to submit budget-reduction proposals. Wise, the music-department chair, submitted a plan that cut more than $500,000. But a joint working group of faculty members and administrators reviewing the proposals adopted a different plan, which Wise and his colleagues allege was influenced by a secret counterproposal they were unaware had been submitted. That proposal, the lawsuit says, was written by faculty members who taught in Saint Rose’s music-industry concentration. Their plan called for the entire music program — and the plaintiffs’ jobs — to be eliminated, and to spare the music-industry concentration and its faculty members.

With one exception, none of the music-industry professors who kept their jobs were as senior as any of the laid-off faculty members. The plaintiffs’ argument — that Saint Rose’s faculty manual requires the college to give preference to faculty members based first on tenure, then seniority, then rank — was accepted by the Albany judge but dismissed by the appellate court on Thursday.

The professors appealed their layoffs to an internal review committee, which ruled in their favor and recommended their reinstatement. But White — at the time the college’s interim president — rejected the appeal, prompting them to pursue legal action.

Meanwhile, the financial circumstances that led to the layoffs have become even more dire. The bond-rating agency Fitch Ratings this month revised Saint Rose’s outlook to negative, citing “sizable, multi-year declines in the College’s already limited student enrollment” that are expected to persist into this fall despite the “comprehensive programmatic and enrollment management overhaul” that was supposed to stabilize the institution’s enrollment. The rating agency noted that Saint Rose’s enrollment was hit especially hard during the pandemic, dropping 15 percent in the fall of 2020 and 18 percent more in the fall of 2021.

Megan Zahneis

Source link