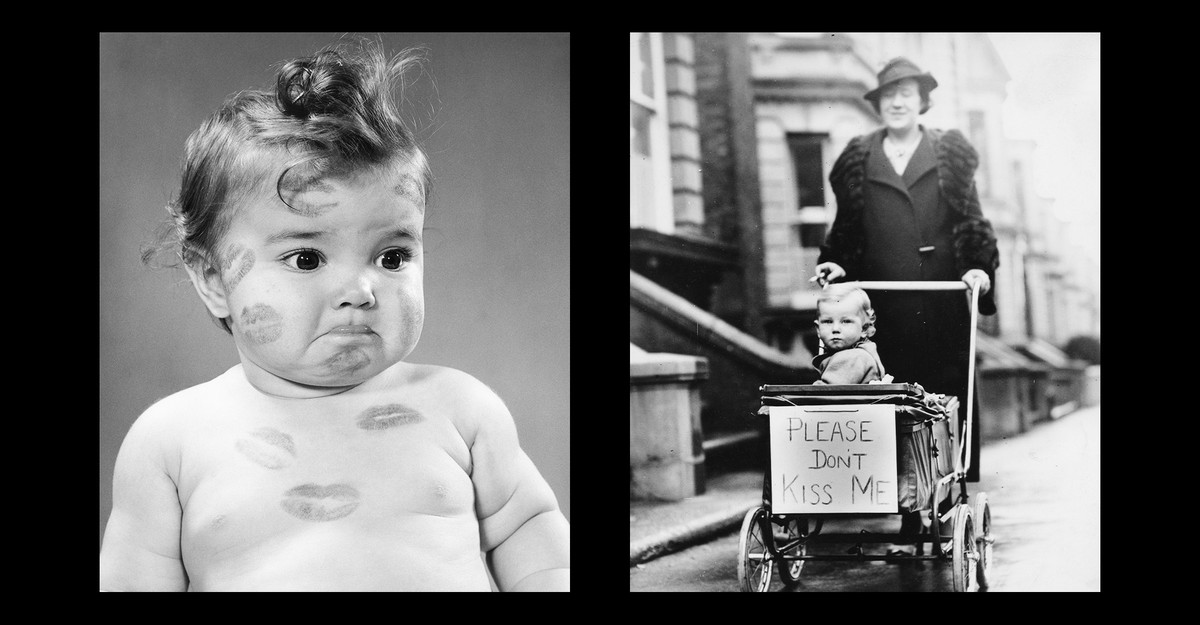

Barack Obama did it. Donald Trump did it. Joe Biden, of course, has done it too. But each of them was wrong: Kissing another person’s baby is just not a good idea.

That rule of lip, experts told me, should be a top priority during the brisk fall and winter months, when flu, RSV, and other respiratory viruses tend to go hog wild (as they are doing right this very moment). “But actually, this is year-round advice,” says Tina Tan, a pediatrician at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. Rain, wind, or shine, outside of an infant’s nuclear family, people should just keep their mouths to themselves. Leave those soft, pillowy cheeks alone!

A moratorium on infant smooching might feel like a bit of a downer—even counterintuitive, given how essential it is for infants and caregivers to touch. But kissing isn’t the only way to show affection to a newborn, and the rationale for cutting back on it specifically is one that most can get behind: keeping those same wee bebes safe. An infant’s immune system is still fragile and unlearned; it struggles to identify infectious threats and can’t marshal much of a defense even when it does. Annette Cameron, a pediatrician at Yale, told me she usually advises parents to avoid public places—church, buses, stores—until their baby is about six weeks old, and able to receive their first big round of immunizations. (And even then, shots take a couple of weeks to kick in.)

The situation grows far less perilous once kids’ vaccine cards start to get more full; past, say, six months of age or so, they’re in much better shape. But risk remains a spectrum, especially when lips get involved. The mouth, I am sorry to tell you, is a weird and gross place, chock-full of saliva, half-chewed flecks of food, and microbes galore; all that schmutz is apt to drool and dribble onto whatever surfaces we drag our faces across. Flu, RSV, rhinovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and the coronaviruses that lead to common colds are among the many respiratory pathogens that hang out in and around our mouth. Although these viruses don’t usually make adults very sick, they can clobber young, unvaccinated kids, whose airways are still small. Health-care workers are seeing a lot of those illnesses now: Cameron recently treated a two-week-old who’d caught rhinovirus and ended up in the ICU.

Also on the list of smoochable threats is herpes simplex 1, the virus responsible for cold sores. “That’s the one I worry about the most,” says Annabelle de St. Maurice, a pediatric-infectious-disease specialist at UCLA and the mother of a 1-year-old daughter. Most American adults harbor chronic HSV-1 infections in their mouth with no symptoms at all, save for maybe the occasional lesion. But the super-transmissible virus can spread throughout the body of an infant, triggering high fevers and seizures bad enough to require a visit to the hospital. For the first few weeks of a baby’s life, anyone with an active cold sore—blood relative, presidential candidate, or both—would do well to keep away. (Even a history of cold sores might warrant extra caution.)

The lip-restraining guidance is most pertinent to people outside an infant’s household, experts told me, which can include extended family. Ideally, even grandparents “should not be kissing on the baby for at least the first few months,” Tan told me. Within a home, siblings attending day care and school—where it’s easy to pick up germs—might also want to sheathe their smackeroos at first. Years ago, Cameron’s own son had to be admitted to the hospital with RSV when he was six weeks old after catching the virus from his 4-year-old sister. Lakshmi Ganapathi, a pediatric-infectious-disease specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital, told me that she didn’t kiss her own two sons on the face before they hit the six-week mark—though experts told me that they don’t expect most parents to get this puritanical about puckering up.

Baby-kissing—especially outside families and tight-knit social circles—isn’t a universal impulse: A few of my friends were rather shocked to hear that such a PSA was even necessary. But people’s threshold for instigating a loving lunge is far lower when it comes to babies than to older kids or adults. One colleague told me that strangers have reached into his daughter’s stroller to stroke her hair; another mentioned that randos have swooped in to tickle his son’s feet. When de St. Maurice takes strolls around her neighborhood with her daughter, she’s surprised by how often casual acquaintances will try to dive-bomb her baby with pursed lips.

Then again, there is perhaps no lure more powerful than a tiny human. Babies snare us visually, with their wide eyes, round cheeks, and button noses; their scent wafts toward us like the heady perfume of a fresh cream scone. (One colleague with kids told me that inhaling that particular odor was, for him, “like huffing glue.”) Among primates, human infants are born especially vulnerable, in desperate need of help, and so we go into overdrive providing it, even to others’ babies, who—at least in our social species—might benefit from communal care. “It’s programmed into us,” Oriana Aragón, a social psychologist at the University of Cincinnati, told me. “I’m able to get really strong reactions out of people with just a photograph.” Even the urge to plant a wet one on someone else’s baby may have adaptive roots in kiss feeding, the practice of delivering pre-chewed meals to an infant lip to lip, says Shelly Volsche, an anthropologist at Boise State University. Kiss-feeding isn’t very popular in the United States today, but it’s still practiced by many groups around the globe.

But as important as these acts are for babies, they can also be at odds with an infant’s health when a bunch of respiratory viruses are swirling about. Those costs aren’t always top of mind when a stranger locks eyes with a tiny human across the way, and it can be “a really awkward conversation,” de St. Maurice told me, to deter someone who just wants to shower affection on your child. Cameron recommends being frank: “I’m just trying to protect my baby.” Physical deterrents can help, too. “Put them in the stroller, put the canopy up, buckle the baby in, make it as difficult as possible,” she said. That’s a lot of barriers for even the most dedicated baby kissers to surmount. De St. Maurice also likes to point out that her little infant, as adorable as she is, “could also potentially transmit something to you.” Plus, by the time they’re six months old, babies may be experiencing their first whiffs of stranger danger and react negatively to unfamiliar hands and mouths. “That’s not particularly good for the baby, and the stranger wouldn’t get anything out of it either,” says Ann Bigelow, a developmental psychologist at St. Francis Xavier University, in Canada.

Again, this advice isn’t meant to starve infants of tactile stimulation. Kids need to be exposed to the outside world and all of its good-germiness. More than that, they need a lot of physical touch. “The skin is our largest sense organ,” Bigelow told me. Skin-to-skin contact stimulates the release of oxytocin, and cements the bond between a caregiver and an infant. Kissing doesn’t have to be the means for giving that affection, though it certainly can be. “Heck, when I’m a grandparent, I’m going to be kissing my grandchild,” Cameron told me. “Just try and stop me.”

Katherine J. Wu

Source link