Juniperus scopulorum

The fantastic, easygoing Rocky Mountain juniper is a North American native that’s used to spruce up formal gardens and natural spaces alike.

Birds love it, it can thrive in difficult-to-fill spots, and it adds year-round color and texture to the garden.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Now, I might be a bit biased. I was raised in the Rockies and more than once I laid out under the sun and inhaled the gin- and cedar-like perfume of these trees.

Every time I catch the aroma of a cultivated juniper, I’m brought back to those lazy summer days in the mountains. I’m sure you’ll love it too.

On top of their low-maintenance demeanor, they’re also just downright good-looking, especially some of the stunning cultivars that have been bred over the years.

So, I think they’re pretty hard to beat. If you’re on the fence, my goal is to have you singing their praises by the time you reach the end of this guide.

To make that happen, here’s what we’ll talk about:

The Rockies are home to some pretty rugged landscapes and many of the plants there had to adapt to survive. These junipers figured out how to thrive even when the environmental conditions got tough.

What Is Rocky Mountain Juniper?

There are 13 native juniper species in the US, and Juniperus scopulorum has become a popular option in home gardens across North America.

It’s also known as the Western red cedar, despite the fact that it’s not a cedar (Cedrus spp.) or arborvitae, which are plants in the Thuja genus that we often call cedars.

Also known as river juniper, cedro rojo, and sabino, it’s the most widely distributed of the North American native junipers.

It has a compact, upright, slightly columnar growth habit, though cultivated varieties can vary in appearance from those with mounded ground-creeping habits to upright weeping types.

The evergreen needles are pointy and gray when they’re young, covered in a white coating. As they mature, the needles become dark blue to light green with scale-like layers. The bark is gray or reddish-brown and peels away from the trunk.

Rocky Mountain juniper is dioecious, and it develops solitary dark blue cones – which we usually call berries – that ripen in their second year, when they develop a white bloom that consists of wild yeast.

Each cone contains one to three seeds, and it can take plants 10 years or more to start producing these.

Animals love the berries, and robins, turkeys, cedar waxwings, and jays all feast on them. Elk, deer, sheep, and antelope eat the needles, but only if nothing tastier is around.

Depending on the cultivar, these plants can grow up to 40 feet tall and 15 feet wide. These are long-lived trees that have been known to survive for up to 2,000 years.

Often confused with its close relative the Eastern red cedar (J. virginiana) with which it hybridizes readily, you can tell the two apart because the Eastern red cedar has darker green foliage and the cones mature in just one year, while junipers take two to three years to mature.

Once again, Eastern red cedars aren’t related to true cedars or arborvitae.

Scopulorum means “of the mountains,” a good indication of where this plant thrives. The Rocky Mountain juniper’s native range extends, as you’d expect, throughout the Rocky Mountains from Mexico north through the Canadian range, and from the western deserts to the Great Plains.

It’s not that this species can only thrive in a mountainous spot with a fabulous view. The reason it grows where it does and across such a broad region is because the bird species that make the Rockies their home have distributed the seeds across this area.

This versatile survivor lives in a huge range of elevations as well, from sea level all the way to 9,000 feet in dry climates. In the wild, you’ll usually find these plants in sheltered areas on rocky cliffs and bluffs.

Extremely drought tolerant compared to most trees, it’s only moderately drought tolerant for a juniper species native to the western US.

It doesn’t do well in humid, hot areas like the southern US and coastal California. Just about anywhere else in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 9 is suitable for growing this species.

Cultivation and History

Native Indigenous populations made good use of J. scopulorum. They ate the berries and used them for medicine.

The bark was made into tools and furniture such as cradles, and the wood was used for fire fuel. They also used the needles as medicine and burned the needles and wood during ceremonies.

Don’t eat too many all at once, though. Blackfoot people used the berries to induce vomiting. On the other end of things, the Crow used it to cure diarrhea.

The Cheyenne burned the leaves to cure a fear of thunder and made an infusion out of the cones and boughs to treat colds and coughs. The wood was thought to have special properties and if you made a flute out of it, you could charm someone into falling in love with you.

Kutenai, Navajo, Sioux, and Thompson people also favored this plant for its cold-easing abilities, and nearly all of the western tribes used it in the home in some form for deterring pests and spirits, for general cleaning, or for keeping disease at bay.

Propagation

You can grow many types of juniper through air layering, but the Rocky Mountain species doesn’t propagate well using this method. Instead, take cuttings or transplant nursery starts into the garden.

Some cultivars can only be propagated by rooting cuttings or planting nursery starts because they don’t produce cones, or the seeds are sterile.

From Cuttings

Junipers propagate well from cuttings and it’s a reliable method to reproduce a plant that you particularly love, which will be a clone of the parent.

The process involves taking a stem cutting that is about nine inches or so long with the diameter of a pencil and placing it in a container filled with an appropriate potting medium.

You’ll keep that moist until the roots begin to form and then you can put it out in the garden.

For a full run-down on the process, you can find more information in our comprehensive juniper growing guide.

Transplanting

I’m assuming your soil doesn’t drain horribly. With good drainage, you can pretty much dig a hole the size of the growing container and toss this plant into it, and that’s it.

If you want to do it right, though, dig a hole twice as wide as the nursery pot and remove the plant from the pot.

Gently loosen the roots and place it in the hole. Fill in around the plant with a half-and-half mixture of the original soil and well-rotted compost. Water well.

How to Grow

I can’t emphasize strongly enough how important it is to select the right spot for these plants. That’s good advice generally, but I assume you’re interested in growing this type of juniper because they’re hardy and pretty much maintenance-free.

These trees have shallow roots – they evolved to grow in rocky areas where their roots can’t penetrate deeply.

Feel free to use them in rock gardens, but don’t put them somewhere with heavy earth and poor drainage. You’ll kill a Rocky Mountain juniper faster that way than anything else.

Some gardeners make the mistake of placing these plants in partial shade, and young plants are perfectly happy there. But as they mature, they need full sun.

If you plant your juniper in part shade, this will increase the risk of disease and it will become leggy with sparse growth.

That’s not to say these plants are prone to disease or to rot. It’s just worth emphasizing that if you want to enjoy all the great things these plants have to offer in terms of hardiness, health, and appearance, you need to plant them in the right spot.

Once there, your job is to keep young plants watered until they become established. This typically takes a year or two. Be sure to provide consistent moisture in the absence of rain.

Junipers don’t need a lot of water once they’re established, but they do need to be kept somewhat moist when they’re young.

Give your plant water when the top inch of soil has dried out. Once it’s established, the top two or three inches can dry out between watering. That might mean you never have to add water if you live somewhere that receives rainfall regularly.

Add some wood mulch around the base of the plants to help retain moisture and keep weeds away. You can also use well-rotted compost, which has the added benefit of providing nutrients.

Growing Tips

- Plant in well-draining soil in full sun.

- Keep young plants well watered. Older plants need less water.

- Wood mulch can help retain moisture and suppress weeds.

Pruning and Maintenance

If I wasn’t clear about it already, I love junipers. But I don’t love junipers that have been sheared within an inch of their lives or trimmed back to naked wood to try and force them into a spot where they don’t belong.

If you choose the right cultivar for your location and you plant it in the right place, you won’t have to do much trimming. Really, the only reason to break out the pruners is to remove dead or diseased wood, or if a branch breaks or sticks out at a funny angle.

Honestly, if you love pruning, there are lots of trees out there that will give you the opportunity. Try a boxwood or a laurel.

Junipers are for those who don’t want to fuss with frequent or intense trimming, though some cultivars are suited to use as topiary.

Learn more about pruning junipers in our guide.

On that note, if you find the process of fertilizing your plants meditative, you’ll need to focus on other species for that as well. Junipers rarely, if ever, need feeding.

If yours is growing in a container, you can go ahead and feed it once every two years – though you won’t need to provide fertilizer at all if you repot or change out the soil periodically.

Down to Earth All Purpose Fertilizer

A mild, balanced fertilizer is all you need. I love Down to Earth’s All-Purpose Mix, which you can pick up at Arbico Organics in one-, five-, and 15-pound compostable containers, but you can choose your favorite.

For tall, thin cultivars, you might want to wrap the tree in burlap or use twine to keep the branches safe during heavy snowstorms. Otherwise, you might notice a few broken branches after heavy snow.

Cultivars to Select

There are two natural variations of Rocky Mountain junipers that have been discovered so far. These are the columnar J. scopulorum var. columnaris, and the mounded shrub known as J. scopulorum var. patens.

Both of these, as well as the species plant, have been used as parents to create some beautiful cultivars. Let’s take a look at a few.

Blue Creeper

‘Monam’ is an extremely popular option and it couldn’t possibly look more different from the original plant.

Instead of a tall, pyramidal shape, this plant is a low-growing creeper that spreads about eight feet wide and grows just two feet high in Zones 3 and up.

The foliage is distinctly and unmistakably blue.

Medora

‘Medora’ has a lovely columnar shape naturally, but if you’re looking for a dreamy topiary, this is an excellent option.

The foliage is dense and upright, with a green-blue hue. This plant grows to 10 feet tall and just two or three feet wide. Grow it in Zones 3 to 9.

Moonglow

‘Moonglow’ is an extremely popular option, in part because of its silvery blue foliage that glows like moonlight. It also maintains a dense, beautifully-formed growth habit without pruning. This cultivar reaches 15 feet tall and six feet wide at maturity.

This towering garden accent has a pyramid shape, and it’s good to go in Zones 3 to 8. It’s also known for being particularly resistant to pests and diseases.

You can – and should! – pick up one of these if you’re interested in a stand-out Rocky Mountain juniper. Head to Fast Growing Trees for a one- to two-, three- to four-, four- to five-, or five- to six-foot tree.

Skyrocket

If I had to bet, I’d guess you’ve seen one of these before in a garden somewhere.

They’re incredibly popular and you see them all over in home gardens and commercial spaces alike. They have a distinct growth habit, staying just three or four feet wide but stretching up to 20 feet tall.

No doubt that’s why they make a beautiful focal point, privacy screen, or container specimen. ‘Skyrocket’ is so narrow that it can squeeze into tiny bare spots, but it’s substantial enough that it can make a statement all on its own.

Zip on over to Home Depot to grab a live plant in a 2.25-gallon pot, suitable for growing in Zones 3 to 9.

Wichita Blue

With a broad, pyramidal form that reaches 15 feet tall and five feet wide, ‘Wichita Blue’ is a stately option that has a distinctly siverly-blue hue.

It stands out from the rest of the greenery in the yard and offers up year-round interest in Zones 3 to 9.

Grab a tree in a gallon-size pot on Amazon if you’re looking for something that brings a unique element to the yard.

Managing Pests and Disease

Rocky mountain junipers are subject to the usual pests and diseases that trouble all plants in the Juniperus genus. Here are the insects and diseases that seem to trouble this species, in particular.

Pests

Mites are by far the most likely pest you’ll run into.

Spider Mites

There are several species of spider mites that feed on Juniperus scopulorum. Spruce spider mites (Oligonychus ununguis) are the most common.

Spruce mites are too small to see with the naked eye, so watch for yellowing or yellow speckling on the needles. The needles may eventually turn brown and fall off when plants are infested.

These pests particularly love cool weather and they can kill plants in a year or so if you don’t intervene.

Trim off any impacted branches and then spray the plants with a strong blast of water. Spray again every few days. This should be done in the morning so the plant can dry in the sun. Keep at it for a few weeks or until symptoms begin to resolve.

Disease

Rocky mountain junipers are hosts for cedar apple rust, caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae. Learn more about this disease in our comprehensive guide. Blight is another disease to watch for.

Cercospora Blight

The fungus Cercospora sequoiae var. juniperi causes a disease known as Cercospora blight.

You’ll typically see symptoms on the young, inner leaves at the bottom of the plant first before it spreads up to the older and exterior leaves. The leaves turn brown and dry.

Prune infected branches. If you caught the disease early, you might be on top of things. But if you don’t catch it early enough, you’ll need to turn to fungicides.

Bonide Liquid Copper Fungicide

You can pick up some Bonide liquid copper fungicide at Arbico Organics in 32-ounce ready-to-use spray, 16- or 32-ounce hose end bottles, or 16-ounce concentrate.

Best Uses

A better question here is what can’t you use Rocky Mountain junipers for?!

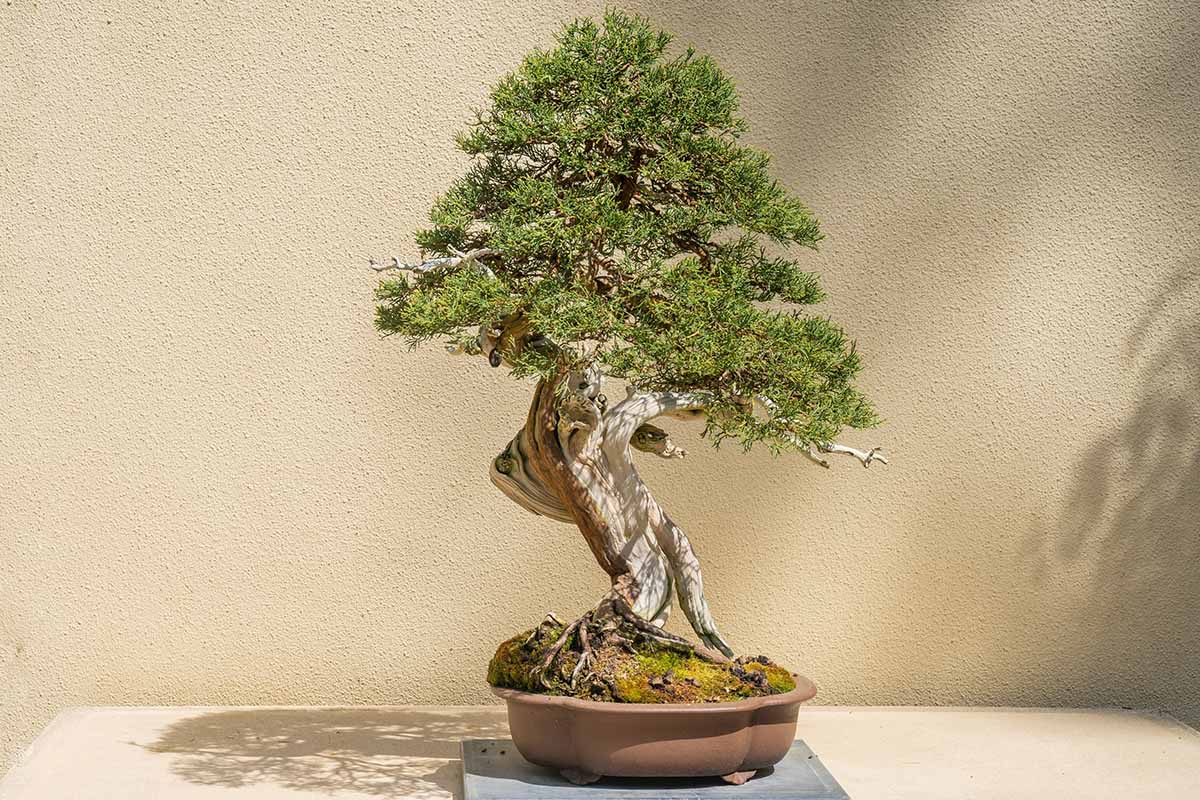

They make an excellent privacy screen, hedge, or specimen. Use them in buffer strips or as a bonsai. Plant them in containers or settle them into the perfect spot as a drought-tolerant ground cover.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody shrub | Foliage Color: | Green to yellow (inconspicuous)/green, blue, silver (blue cones) |

| Native to: | North America | Tolerance: | Drought, depleted soil, pollution, rocky soil |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9 | Soil Type: | Sandy loam |

| Season: | Evergreen | Soil pH: | 5.0-8.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 15 years | Attracts: | Birds |

| Spacing | 2-5 feet, depending on cultivar | Companion Planting: | Coneflower, lavender, rose of Sharon, rose, salvia, sedum |

| Height: | Up to 40 feet tall | Uses: | Bonsai, containers, ground cover, hedge, privacy screen, specimen |

| Spread: | Up to 15 feet wide | Order: | Pinales |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Juniperus |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Spider mites; cedar apple rust, Cercospora blight | Species: | Scopulorum |

Head to the Rockies for a Versatile Shrub

“Easy to care for” is Rocky Mountain juniper’s middle name.

So long as you put it in the right place, it will reward you with year-round color and texture without having to worry much about watering, feeding, or pruning.

Plus, there are so many different cultivars that you have lots of options to choose from.

Which cultivar caught your eye? Where will you use it? Let us know in the comments section below!

The juniper world is huge with so much to know. If you’re interested in finding out more, check out these guides next:

Kristine Lofgren

Source link